1990 Lecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iris Murdoch

Sunday 9th August 2020 www.rmmc.org.uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/tempRMMC/ Last week I shared the first part of the story of Arthur & Ada Salter that had impressed me as I walked the Thames Path. Part Two included today with Part One as reference if you want to re-read! Zoom Church Service Aug 9, 2020 6pm led by Cathy Smith https://astrazeneca.zoom.us/j/99881042054?pwd=UWU3QmE0VkNYNXBMNENLd2dkVmh4QT09 Meeting ID: 998 8104 2054. Password: 562655 0203 481 5237 or 0800 260 5801 7.30pm Monday 10th August The Prayer Course Session 1: Why Pray? https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84151838035?pwd=WFpkZTBjUW9MSW9VL2VMRDBYcU9iUT09 ID: 841 5183 8035 Passcode: 483980. Landline: 0203 051 2874 ‘Prayer is simply paying attention to God, which is a form of love.’ Iris Murdoch Unlike the last course I am thinking of this one being once or twice a month, and with a different aspect of prayer each time it will be easy for people to attend as many sessions as they like and are able. I look for- ward to us learning together. Living Streets and Highways We pray for the living streets in our neighbourhood, where our daily travels begin and end, and our love of God inspires our interactions with our neighbours. In our walks and our rides and our drives and our deliveries, God keep us safe and looking out for others. Somebody during the post-service coffee session on last Sunday's zoom call asked for more de- tails about the Highway Code Consultation. In summary the proposed changes support a heirar- chy of road-users, prioritising people who are most vulnerable to harm, starting with pedestrians, (especially children, older adults and people with disabilities) and stating more clearly how all oth- er road users can reduce the danger they may pose to others. -

HON. GIZ WATSON B. 1957

PARLIAMENTARY HISTORY ADVISORY COMMITTEE AND STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA TRANSCRIPT OF AN INTERVIEW WITH HON. GIZ WATSON b. 1957 - STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA - ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION DATE OF INTERVIEW: 2015-2016 INTERVIEWER: ANNE YARDLEY TRANSCRIBER: ANNE YARDLEY DURATION: 19 HOURS REFERENCE NUMBER: OH4275 COPYRIGHT: PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA & STATE LIBRARY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS NOTE TO READER Readers of this oral history memoir should bear in mind that it is a verbatim transcript of the spoken word and reflects the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Parliament and the State Library are not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein; these are for the reader to judge. Bold type face indicates a difference between transcript and recording, as a result of corrections made to the transcript only, usually at the request of the person interviewed. FULL CAPITALS in the text indicate a word or words emphasised by the person interviewed. Square brackets [ ] are used for insertions not in the original tape. ii GIZ WATSON INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPTS CONTENTS Contents Pages Introduction 1 Interview - 1 4 - 22 Parents, family life and childhood; migrating from England; school and university studies – Penrhos/ Murdoch University; religion – Quakerism, Buddhism; countryside holidays and early appreciation of Australian environment; Anti-Vietnam marches; civil-rights movements; Activism; civil disobedience; sport; studying environmental science; Albany; studying for a trade. Interview - 2 23 - 38 Environmental issues; Campaign to Save Native Forests; non-violent Direct Action; Quakerism; Alcoa; community support and debate; Cockburn Cement; State Agreement Acts; campaign results; legitimacy of activism; “eco- warriors”; Inaugural speech . -

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power

Dollars for Death Say No to Uranium Mining & Nuclear Power Jim Green & Others 2 Dollars for Death Contents Preface by Jim Green............................................................................3 Uranium Mining ...................................................................................5 Uranium Mining in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia..........................5 In Situ Leach Uranium Mining Far From ‘Benign’ by Gavin Mudd.....................8 How Low Can Australia’s Uranium Export Policy Go? by Jim Green................10 Uranium & Nuclear Weapons Proliferation by Jim Falk & Bill Williams..........13 Nuclear Power ...................................................................................16 Ten Reasons to Say ‘No’ to Nuclear Power in Australia by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................16 How to Make Nuclear Power Safe in Seven Easy Steps! by Friends of the Earth, Australia...................................................................18 Japan: One Year After Fukushima, People Speak Out by Daniel P. Aldrich......20 Nuclear Power & Water Scarcity by Sue Wareham & Jim Green........................23 James Lovelock & the Big Bang by Jim Green......................................................25 Nuclear Waste ....................................................................................28 Nuclear Power: Watt a Waste .............................................................................28 Nuclear Racism .................................................................................31 -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Red Flag Over Bermondsey - the Ada Salter Story

7.00 pm SATURDAY 5 DECEMBER 2015 RED FLAG OVER BERMONDSEY - THE ADA SALTER STORY Written and performed by Lynn Morris Directed by Dave Morris Where to start with Ada Salter? She was a true radical, campaigner for equal rights, socialist, republican, pacifist, environmentalist, trade union activist and a leading light in the transformation of the Bermondsey slums in the early part of the 20th century. Born into Methodism, she moved to London and became involved with the Bermondsey Settlement. She became a Quaker in 1914. She and her GP husband, Alfred Salter, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, living and working right in the heart of their community – and having to accept the tragic consequences of their choice. She and her husband were among the founders of the Independent Labour Party in Bermondsey. Ada herself broke through the glass ceiling of her time, becoming both the first woman councillor in London, and then the first woman mayor. Red Flag over Bermondsey explores the private and the public lives of Ada from 1909 until 1922, interwoven with her beloved Ira Sankey hymns and her passion for Handel. Further background about Ada (1866–1942) is to be found at www.quakersintheworld.org The performance lasts 65 minutes without interval. Lynn and Dave Morris are Journeymen theatre and they are committed to performing their work in any venue, theatre or non-theatre. Lynn and David attend Stourbridge Quaker Meeting. Visit the website at: www.journeymentheatre.com for details about the company, current and future productions, and reviews. Contact us at: [email protected] or [email protected] Admission FREE: All profits and donations from Red Flag over Bermondsey will be used to support our work with the Women’s Co-operative of Seir, West Bank, Palestine. -

Influence on the U.S. Environmental Movement

Australian Journal of Politics and History: Volume 61, Number 3, 2015, pp.414-431. Exemplars and Influences: Transnational Flows in the Environmental Movement CHRISTOPHER ROOTES Centre for the Study of Social and Political Movements, School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK Transnational flows of ideas are examined through consideration of Green parties, Friends of the Earth, and Earth First!, which represent, respectively, the highly institutionalised, the semi- institutionalised and the resolutely non-institutionalised dimensions of environmental activism. The focus is upon English-speaking countries: US, UK and Australia. Particular attention is paid to Australian cases, both as transmitters and recipients of examples. The influence of Australian examples on Europeans has been overstated in the case of Green parties, was negligible in the case of Friends of the Earth, but surprisingly considerable in the case of Earth First!. Non-violent direct action in Australian rainforests influenced Earth First! in both the US and UK. In each case, the flow of influence was mediated by individuals, and outcomes were shaped by the contexts of the recipients. Introduction Ideas travel. But they do not always travel in straight lines. The people who are their bearers are rarely single-minded; rather, they carry and sometimes transmit all sorts of other ideas that are in varying ways and to varying degrees discrepant one with another. Because the people who carry and transmit them are in different ways connected to various, sometimes overlapping, sometimes discrete social networks, ideas are not only transmitted in variants of their pure, original form, but they become, in these diverse transmuted forms, instantiated in social practices that are embedded in differing institutional contexts. -

Take Heart and Name WA's New Federal Seat Vallentine 2015 Marks 30 Years Since Jo Vallentine Took up Her Senate Position

Take heart and name WA’s new federal seat Vallentine 2015 marks 30 years since Jo Vallentine took up her senate position, the first person in the world to be elected on an anti-nuclear platform. What better way to acknowledge her contribution to peace, nonviolence and protecting the planet than to name a new federal seat after her? The official Australian parliament website describes Jo Vallentine in this way: Jo Vallentine was elected in 1984 to represent Western Australia in the Senate for the Nuclear Disarmament Party, running with the slogan ‘Take Heart—Vote Vallentine’. She commenced her term in July 1985 as an Independent Senator for Nuclear Disarmament, claiming in her first speech that she was the first member of any parliament in the world to be elected on this platform. When she stood for election again in 1990, she was elected as a senator for The Greens (Western Australia), and was the first Green in the Australian Senate. … During her seven years in Parliament, Vallentine was a persistent voice for peace, nuclear disarmament, Aboriginal land rights, social justice and the environment (emphasis added)i. Jo Vallentine’s parliamentary and subsequent career should be recognised in the named seat of Vallentine because: 1. Jo Vallentine was the first woman or person in several roles, in particular: The first person in the world to win a seat based on a platform of nuclear disarmament The first person to be elected to federal parliament as a Greens party politician. The Greens are now Australia’s third largest political party, yet no seat has been named after any of their political representatives 2. -

Future Regional Nuclear Fuel Cycle Cooperation In

FFUUTTUURREE RREEGGIIOONNAALL NUUCCLLEEAARR FUUEELL CCYYCCLLEE COOOOPPEERRAATTIIOONN INN EAASSTT ASSIIAA:: EENNEERRGGYY SEECCUURRIITTYY COOSSTTSS AANNDD BBEENNEEFFIITTSS Report of the EAST ASIA SCIENCE AND SECURITY PROJECT Prepared for The John T. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Prepared by David von Hippel, Tatsujiro Suzuki, Tadahiro Katsuta, Jungmin Kang, Alexander Dmitriev, Jim Falk, and Peter Hayes Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability at the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim 2130 Fulton Street LM 200, San Francisco, CA 94117 Phone: (415) 422 5523 Fax: (415) 422-5933; e-mail: [email protected] David von Hippel e-mail: [email protected] [June 6, 2010] i Nautilus Institute Executive Summary Over the past two decades, economic growth in East Asia—and particularly in China, the Republic of Korea (ROK), Vietnam, Taiwan, and Indonesia—has rapidly increased regional energy, and especially, electricity needs. As a recent, eye-opening example of these increased needs, China added more than 100 GW of generating capacity—equivalent to 150 percent of the total generation capacity in the ROK as of 2007—in the year 2006 alone, with the vast bulk of that added capacity being coal-fired, with attendant concerns regarding the global climate impacts of steadily increasing coal consumption. Even more striking than growth in primary energy use—and indeed one of its main drivers—has been the increase in electricity generation (and consumption) in the region. With the lessons of the “energy crises” of the 1970s in mind, several of the countries of East Asia—starting with Japan, and continuing with the ROK, Taiwan, and China—have sought to diversify their energy sources and bolster their energy supply security by developing nuclear power. -

New A4 Pages (Page 4)

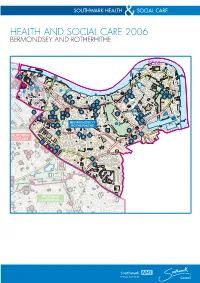

HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE GP Practices Southwark PCT Premises Pharmacies 1 The New Mill Street Surgery (Dr A Campion) 1 Mary Sheridan House 1 A.R. Chemists 1 Wolseley Street, SE1 2BP 11-19 Thomas Street, SE1 9RY 176-178 Old Kent Road, SE1 5TY Tel: 020 7252 1817 2 Mabel Goldwin House Tel: 020 7703 4097 2 Parkers Row Family Practice (Dr S Bhatti) 49 Grange Walk, SE1 3DY 2 ABC Pharmacy 2 Wade House, Parkers Row, SE1 2DN 3 Woodmill Building 243 Southwark Park Road, SE16 3TS Tel: 020 7237 1517 Neckinger, SE16 3QN Tel: 020 7237 1659 3 Alfred Salter Medical Centre (Dr S Bhatti) 4 Bermondsey Health Centre 3 Amadi Chemist 6-8 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW 107 Abbey Street, SE1 3NP Tel: 020 7237 1857 5 John Dixon Clinic Tel: 020 7771 3863 4 The Grange Road Practice (Dr M Brooks) Prestwood House, 4 Bonamy Pharmacy Bermondsey Health Centre, 201-209 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 355 Rotherhithe New Road, 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW Bonamy Estate, SE16 3HF Tel: 020 7237 1078 6 Albion Street Health Centre 87 Albion Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 7JX Tel: 020 7231 9988 5 Bemondsey and Lansdowne Medical Mission, 5 Boots The Chemist PLC (Dr R Torry) 7 St Olave's Nursing Home 15 Ann Moss Way, SE16 2TJ Unit 11-13 Surrey Quays Shopping Centre, Decima Street, SE1 4QX Redriff Road, SE16 9SP 8 Surrey Docks Health Centre Enquiries: 020 7407 0752 Tel: 020 7252 0084 Appointments: 020 7403 36186 Downtown Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 1NP 6 Boots The Chemist PLC 9 Silverlock Clinic 6 -

Local Government for England Report No. 333 LOCAL G

Local Government For England Report No. 333 LOCAL G BOUNDARY C00.II3SIOK FOR- ENGLAHD REPORT NO, LOCAL GOVERin-iEHT. BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOH ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Nicholas Morrison KGB DKPUTY CHAIRMAN • Mr J M Pankin QC MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Mr R R Thornton CB DL Mr D P Harrison ^ -* o - PH Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOR FUTURE ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE BOROUGH OF WELLINGBOROUGH IN THE COUNTY OF NORTHAMPTONSHIRE 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for. the Borough of t r Wellingborough in accordance with the requirements of section 63 of, and » Schedule 9 to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that borough. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in section 6od) and (2) of the 1972 Act, notice was given on 31 December 197'* that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to Wellingborough B-rough Council, copies of which were circulated to Northamptonshire County Council, the Member of Parliament for the constituency concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. 3. The Borough Council were invited to prepare a draft scheme of representation for our consideration. -

Collection Name

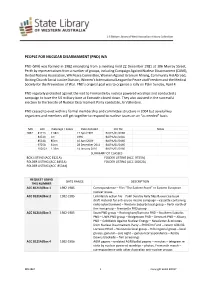

PEOPLE FOR NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT (PND) WA PND (WA) was formed in 1982 emanating from a meeting held 22 December 1981 at 306 Murray Street, Perth by representatives from a number of groups, including Campaign Against Nuclear Disarmament (CANE), United Nations Association, WA Peace Committee, Women Against Uranium Mining, Community Aid Abroad, Uniting Church Social Justice Division, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the Medical Society for the Prevention of War. PND’s original goal was to organise a rally on Palm Sunday, April 4. PND regularly protested against the visit to Fremantle by nuclear powered warships and conducted a campaign to have the US military base at Exmouth closed down. They also assisted in the successful election to the Senate of Nuclear Disarmament Party candidate, Jo Vallentine. PND ceased to exist within a formal membership and committee structure in 2004 but several key organizers and members still get together to respond to nuclear issues on an “as needed” basis. MN ACC meterage / boxes Date donated CIU file Notes 2867 8121A 2.38m 17 April 1991 BA/PA/01/0166 8451A 1m 1996 BA/PA/01/0166 8534A 85cm 16 April 2009 BA/PA/01/0166 9725A 61cm 28 December 2011 BA/PA/01/0166 10202A 1.36m 14 January 2016 BA/PA/01/0166 SUMMARY OF CLASSES BOX LISTING (ACC 8121A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 9725A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8451A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 10202A) FOLDER LISTING (ACC 8534A) REQUEST USING DATE RANGE DESCRIPTION THIS NUMBER ACC 8121A/Box 1 1982-1985 Correspondence – File; “The Eastern Front” re Eastern European nuclear -

Alfred Salter Weekly

Alfred Salter Weekly st 21 May 2021 News from Alfred Salter Primary School Headteacher’s Message Alfred Salter’s Birthday It has been another busy week in school as We will be marking what would have been we near the end of this half term. I Alfred Salter’s birthday on Wednesday conducted a few more tours this week for 16th June 2021, which falls during D&T our new Reception parents and the feedback and week. The focus will be on the humanitarian work comments have been very positive. As these tours which he and his wife Ada Salter did for the have been very successful, we will be doing the community and the love they had for Bermondsey same after half term for our new Nursery families and Rotherhithe. We are hoping that the weather who will be joining the school in September. will be kind to us and that we can bring the whole I held several parental consultation meetings on the school together on the astroturf, in socially new statutory Relationships and Sex Education distanced bubbles, so that we can experience being (RSE) and health education curriculum on Thursday. together as a whole school after so long apart. We Thank you to all the parents and carers that will be sharing details shortly. attended. There were some really important queries Class Photos raised and questions asked. I hope that you found Braiswick, the school photographer will the meetings informative and any hesitations or be in on the morning of Monday 14th worries around RSE have been eased.