Rethinking Intellectual Histories: Gender, Generation and Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iris Murdoch

Sunday 9th August 2020 www.rmmc.org.uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/tempRMMC/ Last week I shared the first part of the story of Arthur & Ada Salter that had impressed me as I walked the Thames Path. Part Two included today with Part One as reference if you want to re-read! Zoom Church Service Aug 9, 2020 6pm led by Cathy Smith https://astrazeneca.zoom.us/j/99881042054?pwd=UWU3QmE0VkNYNXBMNENLd2dkVmh4QT09 Meeting ID: 998 8104 2054. Password: 562655 0203 481 5237 or 0800 260 5801 7.30pm Monday 10th August The Prayer Course Session 1: Why Pray? https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84151838035?pwd=WFpkZTBjUW9MSW9VL2VMRDBYcU9iUT09 ID: 841 5183 8035 Passcode: 483980. Landline: 0203 051 2874 ‘Prayer is simply paying attention to God, which is a form of love.’ Iris Murdoch Unlike the last course I am thinking of this one being once or twice a month, and with a different aspect of prayer each time it will be easy for people to attend as many sessions as they like and are able. I look for- ward to us learning together. Living Streets and Highways We pray for the living streets in our neighbourhood, where our daily travels begin and end, and our love of God inspires our interactions with our neighbours. In our walks and our rides and our drives and our deliveries, God keep us safe and looking out for others. Somebody during the post-service coffee session on last Sunday's zoom call asked for more de- tails about the Highway Code Consultation. In summary the proposed changes support a heirar- chy of road-users, prioritising people who are most vulnerable to harm, starting with pedestrians, (especially children, older adults and people with disabilities) and stating more clearly how all oth- er road users can reduce the danger they may pose to others. -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain • Fairfax Mansions

Vol. XVII No. 7 July, 1962 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN • FAIRFAX MANSIONS. FINCHLEY RD. (corner Fairfax Rd.). London. N.W.I Offset and ConMuUiitg Hours: Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096/7 (General OIkce and Welfare tor tha Aged) Moi\day to Thursday 10 a.in.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency, annually licensed bv the L.C.C,, and Social Services Dept.) Friday 10 ajn.—l p.m. Ernst Kahn Austrian baroque civilisation, tried to cope with their situation. Schnitzler, more fortunate than Weininger, if only through his exterior circum stances, knew much about the psychological struc THE YOUNG GENERATION CARRIES ON ture of Viennese middle-class s(Kiety and Jewry. The twilight, uncertainly and loneliness of the human soul attracted him, but his erotism is half- Sixth Year Book of the Leo Baeck Institute playful, half-sorrowful and does not deceive him about the truth that ". to write means to sit Those amongst us who remember our German- To some extent these achievements were due to in judgment over one's self". It enabled him to Jewish past are bound to wonder who will carry the Rabbi's charm which attracted Polish Jews objectivise the inner struggles of Jews who sought On with the elucidation of the relevant problems and German high-ranking officers and aristocrats the " Way into the Open ", i.e., into assimilation in once the older witnesses are no longer available. alike with whom he collaborated very closely. its different forms. The Year Book 1961* brings this home to us by This went so far that the German officials called Weininger. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Red Flag Over Bermondsey - the Ada Salter Story

7.00 pm SATURDAY 5 DECEMBER 2015 RED FLAG OVER BERMONDSEY - THE ADA SALTER STORY Written and performed by Lynn Morris Directed by Dave Morris Where to start with Ada Salter? She was a true radical, campaigner for equal rights, socialist, republican, pacifist, environmentalist, trade union activist and a leading light in the transformation of the Bermondsey slums in the early part of the 20th century. Born into Methodism, she moved to London and became involved with the Bermondsey Settlement. She became a Quaker in 1914. She and her GP husband, Alfred Salter, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, living and working right in the heart of their community – and having to accept the tragic consequences of their choice. She and her husband were among the founders of the Independent Labour Party in Bermondsey. Ada herself broke through the glass ceiling of her time, becoming both the first woman councillor in London, and then the first woman mayor. Red Flag over Bermondsey explores the private and the public lives of Ada from 1909 until 1922, interwoven with her beloved Ira Sankey hymns and her passion for Handel. Further background about Ada (1866–1942) is to be found at www.quakersintheworld.org The performance lasts 65 minutes without interval. Lynn and Dave Morris are Journeymen theatre and they are committed to performing their work in any venue, theatre or non-theatre. Lynn and David attend Stourbridge Quaker Meeting. Visit the website at: www.journeymentheatre.com for details about the company, current and future productions, and reviews. Contact us at: [email protected] or [email protected] Admission FREE: All profits and donations from Red Flag over Bermondsey will be used to support our work with the Women’s Co-operative of Seir, West Bank, Palestine. -

The Labour Party and the Idea of Citizenship, C. 193 1-1951

The Labour Party and the Idea of Citizenship, c. 193 1-1951 ABIGAIL LOUISA BEACH University College London Thesis presented for the degree of PhD University of London June 1996 I. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the development and articulation of ideas of citizenship by the Labour Party and its sympathizers in academia and the professions. Setting this analysis within the context of key policy debates the study explores how ideas of citizenship shaped critiques of the relationships between central government and local government, voluntary groups and the individual. Present historiographical orthodoxy has skewed our understanding of Labour's attitude to society and the state, overemphasising the collectivist nature and centralising intentions of the Labour party, while underplaying other important ideological trends within the party. In particular, historical analyses which stress the party's commitment from the 1930s to achieving the transition to socialism through a strategy of planning, (of industrial development, production, investment, and so on), have generally concluded that the party based its programme on a centralised, expert-driven state, with control removed from the grasp of the ordinary people. The re-evaluation developed here questions this analysis and, fundamentally, seeks to loosen the almost overwhelming concentration on the mechanisms chosen by the Labour for the implementation of policy. It focuses instead on the discussion of ideas that lay behind these policies and points to the variety of opinions on the meaning and implications of social and economic planning that surfaced in the mid-twentieth century Labour party. In particular, it reveals considerable interest in the development of an active and participatory citizenship among socialist thinkers and politicians, themes which have hitherto largely been seen as missing elements in the ideas of the interwar and immediate postwar Labour party. -

Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5Th Edition 2021

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme 5th Edition | 2021 Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5th Edition 2021 Contents 000 Geography and general works ............................................................... 5 Local places, notable passing events, royalty and the borough, world wars 100 Biography ................................................................................................ 7 Local people, collected biographies, lists of names 200 Religion, philosophy and ethics ............................................................ 7 Religious and ethical organisations, places of worship, religious life and education 300 Social sciences ..................................................................................... 11 Racism, women, LGBTQ+ people, politics, housing, employment, crime, customs 400 Ethnic groups, migrants, race relations ............................................. 19 Migration, ethnic groups and communities 500 Science .................................................................................................. 19 Physical geography, archaeology, environment, biology 600 Applied sciences ................................................................................... 19 Public health, medicine, business, shops, inns, markets, industries, manufactures 700 Arts and recreation ............................................................................... 24 Planning, parks, land and estates, fine arts, -

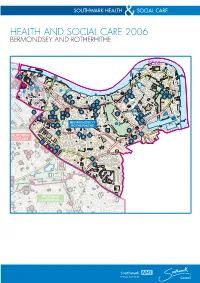

New A4 Pages (Page 4)

HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE 2006 BERMONDSEY AND ROTHERHITHE GP Practices Southwark PCT Premises Pharmacies 1 The New Mill Street Surgery (Dr A Campion) 1 Mary Sheridan House 1 A.R. Chemists 1 Wolseley Street, SE1 2BP 11-19 Thomas Street, SE1 9RY 176-178 Old Kent Road, SE1 5TY Tel: 020 7252 1817 2 Mabel Goldwin House Tel: 020 7703 4097 2 Parkers Row Family Practice (Dr S Bhatti) 49 Grange Walk, SE1 3DY 2 ABC Pharmacy 2 Wade House, Parkers Row, SE1 2DN 3 Woodmill Building 243 Southwark Park Road, SE16 3TS Tel: 020 7237 1517 Neckinger, SE16 3QN Tel: 020 7237 1659 3 Alfred Salter Medical Centre (Dr S Bhatti) 4 Bermondsey Health Centre 3 Amadi Chemist 6-8 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW 107 Abbey Street, SE1 3NP Tel: 020 7237 1857 5 John Dixon Clinic Tel: 020 7771 3863 4 The Grange Road Practice (Dr M Brooks) Prestwood House, 4 Bonamy Pharmacy Bermondsey Health Centre, 201-209 Drummond Road, SE16 4BU 355 Rotherhithe New Road, 108 Grange Road, SE1 3BW Bonamy Estate, SE16 3HF Tel: 020 7237 1078 6 Albion Street Health Centre 87 Albion Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 7JX Tel: 020 7231 9988 5 Bemondsey and Lansdowne Medical Mission, 5 Boots The Chemist PLC (Dr R Torry) 7 St Olave's Nursing Home 15 Ann Moss Way, SE16 2TJ Unit 11-13 Surrey Quays Shopping Centre, Decima Street, SE1 4QX Redriff Road, SE16 9SP 8 Surrey Docks Health Centre Enquiries: 020 7407 0752 Tel: 020 7252 0084 Appointments: 020 7403 36186 Downtown Road, Rotherhithe, SE16 1NP 6 Boots The Chemist PLC 9 Silverlock Clinic 6 -

A Rhetorical History of the British Constitution of Israel, 1917-1948

A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION OF ISRAEL, 1917-1948 by BENJAMIN ROSWELL BATES (Under the Direction of Celeste Condit) ABSTRACT The Arab-Israeli conflict has long been presented as eternal and irresolvable. A rhetorical history argues that the standard narrative can be challenged by considering it a series of rhetorical problems. These rhetorical problems can be reconstructed by drawing on primary sources as well as publicly presented texts. A methodology for doing rhetorical history that draws on Michael Calvin McGee's fragmentation thesis is offered. Four theoretical concepts (the archive, institutional intent, peripheral text, and center text) are articulated. British Colonial Office archives, London Times coverage, and British Parliamentary debates are used to interpret four publicly presented rhetorical acts. In 1915-7, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration and the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. Although these documents are treated as promises in the standard narrative, they are ambiguous declarations. As ambiguous documents, these texts offer opportunities for constitutive readings as well as limiting interpretations. In 1922, the Mandate for Palestine was issued to correct this vagueness. Rather than treating the Mandate as a response to the debate between realist foreign policy and self-determination, Winston Churchill used epideictic rhetoric to foreclose a policy discussion in favor of a vote on Britain's honour. As such, the Mandate did not account for Wilsonian drives in the post-War international sphere. After Arab riots and boycotts highlighted this problem, a commission was appointed to investigate new policy approaches. In the White Paper of 1939, a rhetoric of investigation limited Britain's consideration of possible policies. -

Labour and the Politics of Alcohol: the Decline of a Cause

Labour and the politics of alcohol: The decline of a cause A report produced for the Institute of Alcohol Studies By Dr Peter Catterall University of Westminster September 2014 About the Author Peter Catterall is Reader in History at the University of Westminster and Chair of the George Lansbury Memorial Trust. He has written extensively on modern British politiCal history, and is Currently Completing a book on RadiCalism, Righteousness and Religion: Labour and the Free Churches 1918-1939, to be published by Bloomsbury. Please note that the views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not represent the views of the Institute of AlCohol Studies Institute of AlCohol Studies AllianCe House 12 Caxton Street London SW1H 0QS LABOUR AND THE POLITICS OF ALCOHOL: THE DECLINE OF A CAUSE1 Dr Peter Catterall, University of Westminster The index to James Nicholls’ recent survey of the history of the drink question in England to the present day contains precisely no references to the Labour Party.2 Anxiety to curb the deleterious effects of alcohol is presented therein largely as a Liberal preserve. He is not alone in overlooking the importance of the drink question in the early history of the Labour Party. Even John Greenaway’s analysis of the high politics of alcohol since 1830 only briefly discusses Labour’s attitude to the subject, and then primarily in terms of intra- party divisions.3 Many Labour historians have also largely written the subject out of the Party’s history. There is only brief mention of ‘fringe issues like temperance’ -

Spiritual Leaders in the IFOR Peace Movement

A Lexicon of Spiritual Leaders In the IFOR Peace Movement Version 4 Page 1 of 156 10.4.2012 Dave D’Albert Disclaimer:................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Forward:...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The Start of it all............................................................................................................................................................... 6 1914............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Bilthoven Meeting 1919............................................................................................................................................... 6 Argentina.......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Adolfo Pérez Esquivel 1931-....................................................................................................................................... 7 Others with little or no information............................................................................................................................... 7 D. D. Lura-Villanueva ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1986 The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900 Stephen J. O'Neil Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation O'Neil, Stephen J., "The Origins and Development of the Fabian Society, 1884-1900" (1986). Dissertations. 2491. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2491 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1986 Stephen J. O'Neil /11/ THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE FABIAN SOCIETY, 1884-1900 by Stephen J. O'Neil A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 1986 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is the product of research over several years' span. Therefore, while I am endebted to many parties my first debt of thanks must be to my advisor Dr. Jo Hays of the Department of History, Loyola University of Chicago; for without his continuing advice and assistance over these years, this project would never have been completed. I am also grateful to Professors Walker and Gutek of Loyola who, as members of my dissertation committee, have also provided many sug gestions and continual encouraqement in completing this project.