Greater Manchester's Ever Changing Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advisory Visit River Bollin, Styal Country Park, Cheshire February

Advisory Visit River Bollin, Styal Country Park, Cheshire February 2010 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust to the River Bollin, Cheshire on 19th February 2010. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Kevin Nash (Fisheries Technical Specialist) and Andy Eaves (Fisheries Technical Officer) of the Environment Agency (EA), North West Region (South Area). Normal convention is applied throughout the report with respect to bank identification, i.e. the banks are designated left hand bank (LHB) or right hand bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. 2.0 Catchment / Fishery Overview The River Bollin is 49 km long and rises in the edge of Macclesfield Forest, flowing west to join the River Mersey (Manchester Ship Canal) near Lymm. The River Dean is the major tributary of the Bollin, and the catchment area totals 273 km2. The section of river visited flows through Styal Country Park, downstream of Quarry Bank Mill, and is owned by the National Trust. A previous Wild Trout Trust visit was carried out further downstream at the National Trust property at Dunham Massey. The Bollin falls within the remit of the Mersey Life Project which aims to carry out a phased programme of river restoration, initially focussing on the non-tidal section of the River Mersey, the River Bollin and River Goyt (http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/homeandleisure/wildlife/102362.aspx). The construction of fish passes on Heatley and Bollington Mill weirs in the lower Bollin catchment means it is now possible for migratory species (e.g. -

An Assessment of Trafford's Public Rights of Way Network

An Assessment of Trafford’s Public Rights of Way Network Stage One of the Rights of Way Improvement Plan for Trafford DECEMBER 2007 An Assessment of Trafford’s Rights of Way Network Stage 1 of the Rights of Way improvement Plan for Trafford MBC December 2007 Prepared By: For: Landscape Practice Trafford MBC MEDC The Built Environment PO Box 463 2nd Floor Town Hall Waterside House Manchester Sale Waterside M60 3NY Sale M33 7ZF Document : Stage 1 ROWIP for Trafford MBC Prepared By: Checked By: Issue Date Issue 1 14/06/07 Becky Burton Ian Graham Issue 2 21/12/07 Project Manager Project Director Ref: XX32857/DOC/30/03/ Issue 2 XX32/DOC/30/03 December 07 Contents Page No Lists of Tables and Figures i Glossary ii 1.0 What is a Rights of Way Improvement Plan (ROWIP) 1 2.0 Introduction to Trafford 3 3.0 Trafford’s Approach to Delivering their ROWIP 4 4.0 Legal Definitions 5 5.0 Rights of Way and the Local Transport Plan 9 6.0 Linking the ROWIP to other Documents and Strategies 13 7.0 Network Comparisons 20 8.0 Management of Trafford’s PROW 21 9.0 Consultation 22 9.1 Consultation Process 22 9.2 Summary of the Questionnaire Results 24 10.0 Assessment of the Current Provision and Future Demand 26 10.1 The Current Definitive Map and Statement 26 10.2 Ease of Use – The Existing Condition of the Rights 28 of Way Network 10.3 The Needs and Demands of the User 33 11.0 Conclusions 39 XX32/DOC/30/03 December 07 Appendices Appendix 1 List of Consultees 42 Appendix 2 Results of the Trafford MBC Rights of Way Improvement 46 Plan Consultation Appendix 3 Home Locations of Respondents to Trafford ROWIP 93 Questionnaire Appendix 4 Copy of the Questionnaire 94 Appendix 5 Copy of the Consultation Letter 97 XX32/DOC/30/03 December 07 List of Maps, Tables and Figures Page No. -

Springwood Farm Cowlishaw Brow, Romiley

G COIGNE H LM N G COIGNE H LM N G COIGNE H LM N G COIGNE H LM N G COIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMA GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGN HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE HALMAN GASCOIGNE -

Oresome North Pennines: Site Overview

OREsome North Pennines: Site Overview Whitesike and Bentyfield lead mines and ore works Fig. 1: Whitesike and Bentyfield Mines viewed from the B6277 road, looking east SAM list entry number: 1015832 Other designations: Whitesike Mine and Flinty Fell SSSI Grid ref.: NY751425 County: Cumbria District/Parish: Eden, Alston Moor Altitude: 430-460m SAM area: 3.32 hectares Habitats: Narrow valley with sheep pasture, scrub and mine workings Highlights Archaeology: The dressing floors of Whitesike and Bentyfield ore works retain especially deep stratified deposits including areas that are waterlogged, which is ideal for the preservation of organic materials, such as wood and leather. Nationally important remains of 19th century ore processing equipment is considered to survive within these deposits, which will provide very valuable information about ore processing technology. The two linked mines form typical examples of mid-19th century mine complexes and as they are crossed by a footpath, they are an educational resource and public amenity. Botany: This site includes one of the richest calaminarian grassland communities remaining on the North Pennine lead mines, with the full suite of North Pennine metallophyte plants all thriving and a rich diversity of other plants, lichens and bryophytes. Thrift is declining throughout this area and the vigorous population at Whitesike may be the largest and most healthy left in the North Pennines, so it is considered to be of at least regional importance. 1 Geology: There is an exposure of the sponge and coral bearing limestone at location 6 on the geological features map. This bed is widely present across the Northern Pennines, but its location here alongside a footpath makes this an important educational and interpretation resource. -

The Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns

‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns A Roberts PhD 2016 ‘Views Grim But Splendid’ - Te Urban Image of North-West English Industrial Towns Amber Roberts o 2016 Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 21 01 Literature Review 53 02 Research Methods 81 Region’ 119 155 181 215 245 275 298 1 Acknowledgements 2 3 Abstract ‘What is the urban image of the north- western post-industrial town?’ 4 00 Introduction This research focuses on the urban image of North West English historic cultural images, the built environment and the growing the towns in art, urban planning and the built environment throughout case of Stockport. Tesis Introduction 5 urban development that has become a central concern in the towns. 6 the plans also engage with the past through their strategies towards interest in urban image has led to a visual approach that interrogates This allows a more nuanced understanding of the wider disseminated image of the towns. This focuses on the represented image of the and the wider rural areas of the Lancashire Plain and the Pennines. Tesis Introduction 7 restructuring the town in successive phases and reimagining its future 8 development of urban image now that the towns have lost their Tesis Introduction 9 Figure 0.1, showing the M60 passing the start of the River Mersey at Stockport, image author’s own, May 2013. 10 of towns in the North West. These towns have been in a state of utopianism. persistent cultural images of the North which the towns seek to is also something which is missing from the growing literature on Tesis Introduction 11 to compare the homogenous cultural image to the built environment models to follow. -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

The Link, Barbara)

Part of East Cheshire and Derbyshire Borders Missional Partnership (United Reformed Church ) TTHHEE LLIINNKK NOVEMBER 2020 “The East Cheshire and Derbyshire Borders is a Christian Church, living out the love of God by reaching into the heart of each community and responding to its needs” 1 Dear Friends, November starts with All Saints day which this year is on a Sunday followed by All Souls day on the Monday. This year, more than any other, I think we need to pause and remember all those for whom this year has brought grief and loss when the full celebration of the life of a loved one has been limited and constrained by our journey with ‘the virus’. Remember all the family and friends of the neighbour whose cortege you watched pass, all the individuals who stood at arm’s length from those they would have embraced, all the young people whose first experience of loss has been robbed of the communal and supportive togetherness of grief. Remember the fellowship of the church and our losses, and remember those whose grief remains raw because the opportunities to fellowship have been so few. As we move into winter and the hope of spring seems so far away let our prayer life become deeper and richer as we remember all saints, all souls, held by the Love of God AND all us ‘saints below’ who need the love of friend and stranger to help us through. Every Blessing Alison 2 Prayer and Sunday Service Phoneline: 0161 509 4264 The prayerline will be refreshed on Monday, Wednesday and Friday with a short service being offered over Saturday and Sunday. -

Exploring Greater Manchester

Exploring Greater Manchester a fieldwork guide Web edition edited by Paul Hindle Original printed edition (1998) edited by Ann Gardiner, Paul Hindle, John McKendrick and Chris Perkins Exploring Greater Manchester 5 5. Urban floodplains and slopes: the human impact on the environment in the built-up area Ian Douglas University of Manchester [email protected] A. The River Mersey STOP 1: Millgate Lane, Didsbury The urban development of Manchester has modified From East Didsbury station and the junction of the A34 runoff to rivers (see Figure 1), producing changes in and A5145, proceed south along Parrs Wood Road and into flood behaviour, which have required expensive remedial Millgate Lane, Stop at the bridge over the floodbasin inlet measures, particularly, the embankment of the Mersey from channel at Grid Reference (GR) 844896 (a car can be turned Stockport to Ashton weir near Urmston. In this embanked round at the playing fields car park further on). Looking reach, runoff from the urban areas includes natural channels, south from here the inlet channel from the banks of the storm drains and overflows from combined sewers. Mersey can be seen. At flood times the gates of the weir on Alternative temporary storages for floodwaters involve the Mersey embankment can be opened to release water into release of waters to floodplain areas as in the Didsbury flood the Didsbury flood basin that lies to the north. Here, and at basin and flood storage of water in Sale and Chorlton water other sites along the Mersey, evidence of multi-purpose use parks. This excursion examines the reach of the Mersey from of the floodplain, for recreation and wildlife conservation as Didsbury to Urmston. -

The Friends of Reddish South Station Newsletter

BusinesName The Friends of Reddish South Station Newsletter: Winter 2014 As you can see on the map,(far left) our line is fea- tured, to it’s cur- rent weekly desti- nation, Staly- bridge. Pictured left, current routes for Greater Manchester & beyond, run by There is an under- Northern Rail, including our ‘service’ used line in exis- running to Stalybridge tence that goes into Manchester Victoria, avoiding Guide Bridge, Sta- lybridge and Ashton –u -Lyne going via Ashton Moss which could be used for our proposed, reintro- duced regular passenger service Pictured right the ‘East Manchester Corri- dor, as proposed by The Friends Campaign Group to take us to Manchester Victoria and beyond to the North and Stockport to the South After our meeting with one of the Inside this shortlisted companies for North- issue: ern Rail & Transpennine fran- consultation– in which he has Go-Ahead for a meeting to be chises Arriva Trains, in Septem- presented an excellent busi- scheduled in January 2015 Hallowe’en Folk 2 ber, the Friends of Reddish ness case. and First Group, who are one Train South & Denton Stations of the shortlisted companies Arriva Stakeholder Manager Trampower 3 (FORSADS) campaign group has for the Transpennine Fran- meeting been very active in representing Katherine Miller, and Railfu- chise. our campaign. ture representative Trevor Community rail 4 Bridge were interested in our Railfuture are hoping to hold station adoption We met again with Arriva trains; campaign. We were unusual in further stakeholder days with day a day arranged by Railfuture for that most other groups were Govia & Abellio. -

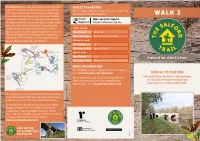

Walk 3 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is the Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 3 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 92, 93, 95 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location Littleton Road Post Office Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. During the walk Bus Number 484 Blackleach Country Park Bus stop location Agecroft Road 5 3 Clifton Country Park End of walk 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus Number 8, 22 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours Kersal Bus stop location Manchester Road, St Annes’s church 2 Vale 6 Worsley 7 Eccles Chat 1 more information Moss 8 Barton For information on any changes in the route please Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays go to visitsalford.info/thesalfordtrail kersal to clifton Little Woolden 10 For background on the local history that you will This walk follows the River Irwell upstream Moss as it meanders through woodland and Irlam come across on the trail or for information on wildlife please go to thesalfordtrail.btck.co.uk open spaces to a large country park. -

River Irk – Greater Manchester

River Irk – Greater Manchester An advisory visit carried out by the Wild Trout Trust – Feb 2015 1 1. Introduction This report is the output of a Wild Trout Trust Advisory Visit (AV) undertaken along approximately 3km of the River Irk in Greater Manchester. The visit was carried out by Dr. Paul Gaskell and hosted by Jo Fraser (Groundwork North West), Mike Duddy (Salford Friendly Anglers) and Dave Barlow (Manchester City Council). The River Irk was walked from an upstream limit at NGR (National Grid Reference) SD 86762 05493 to a downstream limit at SD 83972 03627 Throughout the report, normal convention is followed with respect to bank identification i.e. banks are designated Left Hand Bank (LHB) or Right Hand Bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. Figure 1: Map overview of the catchment including upstream (yellow triangle) and downstream (red dot) limits of inspected reaches 2. Catchment overview The surveyed sections of watercourse are all captured within a single waterbody (GB112069061130); listed as River Irk – Wince Brook to Moston Brook. A number of the parameters are judged to be of less than “Good Potential” for this heavily modified waterbody (e.g. excerpted data given in Table 1.) – giving an overall current and projected ecological potential of “Moderate”. The stand-out assessment results are those for “Phosphate” and “Invertebrate” parameters that are judged to be of “Poor” and “Bad” potential respectively; resulting in an overall biological quality of “Bad”. The presence of a detergents factory (with associated, documented pollution and fish-kill incidents) is a fundamental issue for this section of the River Irk. -

Manchester M2 6AN Boyle 7 C Brook Emetery Track Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911

Port Salford Project Building Demolitions and Tree Removal Plan Peel Investments (North) Ltd Client Salford CC LPA Date: 28.04.04 Drawing No.: 010022/SLP2 Rev C Scale: 1:10 000 @Application A3 Site Boundary KEY Trees in these areas to be retained. Scattered or occasional trees within these areas to be removed SB 32 Bdy t & Ward Co Cons SL 42 Const Bdy Boro Chat Moss CR 52 Buildings to be Demolished MP 25.25 OAD B 62 ODDINGTON ROA STANNARD R Drain 9 8 72 D 83 43 5 6 GMA PLANNING M 62 36 35 SP 28 35 27 48 3 7 2 0 19 4 0 Drain C HA Drain TLEY ROAD 3 MP 25.25 6 23 King Street, Manchester M2 6AN 12 Planning and Development Consultants Chat Moss 11 CR 32 rd Bdy Wa nst & Co Co Bdy Const e-mail [email protected] o Bor 2 53 8 1 Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911 22 Barton Moss 10 16 ROAD F ETON OXHIL BRER 9 rain 43 D L ROAD 23 Drain 2 0 St Gilbert's 33 Catholic Church MP 25 Presbytery 10 3 2 2 4 Drain Barton Moss 2 Drain Drain CR Drain 1 13 15 Co Const Bdy 6 Track Barton Moss 16 Dra Boro Const and Ward Bdy in MP 24.75 27 Eccles C of E High S Drain FLEET ROAD 6 3 ORTH 26 N SL chool D rain 0 3 Drain 39 Drai n 36 Drain BUC KT HORN D E L OA R Drain AN E D ra ILEY in H M 62 53 44 51 55 Dra 5 9 0 5 in M 62 Drain Brookhouse k Sports Centre Barton Moss Primary School rac T 0 6 63 H ILEY ROA D 6 N 5 O BU RTH D 78 rai 2 CK FLEE n T 67 4 35 H O 3 3 54 RN LA 6 T Pavilion 3 ROAD 75 N 74 E 34 27 25 18 78 6 20 7 80 88 Drain 1 1 TRIPPIER ROAD 6 56 23 58 0 30 6 3 1 n 32 55 89 9 2 7 Drai 6 1 9 6 93 64 3 2 15 95 59 ROCHFORD R 59 2 9 15 66