David Hockney and the Memory of Michelangelo Raymond Carlson Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First-Ever Exhibition of British Pop Art in London

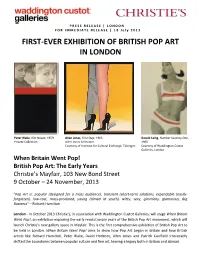

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 1 8 J u l y 2 0 1 3 FIRST- EVER EXHIBITION OF BRITISH POP ART IN LONDON Peter Blake, Kim Novak, 1959 Allen Jones, First Step, 1966 Gerald Laing, Number Seventy-One, Private Collection Allen Jones Collection 1965 Courtesy of Institute for Cultural Exchange, Tübingen Courtesy of Waddington Custot Galleries, London When Britain Went Pop! British Pop Art: The Early Years Christie’s Mayfair, 103 New Bond Street 9 October – 24 November, 2013 "Pop Art is: popular (designed for a mass audience), transient (short-term solution), expendable (easily- forgotten), low-cost, mass-produced, young (aimed at youth), witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, Big Business" – Richard Hamilton London - In October 2013 Christie’s, in association with Waddington Custot Galleries, will stage When Britain Went Pop!, an exhibition exploring the early revolutionary years of the British Pop Art movement, which will launch Christie's new gallery space in Mayfair. This is the first comprehensive exhibition of British Pop Art to be held in London. When Britain Went Pop! aims to show how Pop Art began in Britain and how British artists like Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, David Hockney, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield irrevocably shifted the boundaries between popular culture and fine art, leaving a legacy both in Britain and abroad. British Pop Art was last explored in depth in the UK in 1991 as part of the Royal Academy’s survey exhibition of International Pop Art. This exhibition seeks to bring a fresh engagement with an influential movement long celebrated by collectors and museums alike, but many of whose artists have been overlooked in recent years. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

Frank Bowling Cv

FRANK BOWLING CV Born 1934, Bartica, Essequibo, British Guiana Lives and works in London, UK EDUCATION 1959-1962 Royal College of Art, London, UK 1960 (Autumn term) Slade School of Fine Art, London, UK 1958-1959 (1 term) City and Guilds, London, UK 1957 (1-2 terms) Regent Street Polytechnic, Chelsea School of Art, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1962 Image in Revolt, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1963 Frank Bowling, Grabowski Gallery, London, UK 1966 Frank Bowling, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1971 Frank Bowling, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, USA 1973 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1973-1974 Frank Bowling, Center for Inter-American Relations, New York, New York, USA 1974 Frank Bowling Paintings, Noah Goldowsky Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1975 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1976 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Watson/de Nagy and Co, Houston, Texas, USA 1977 Frank Bowling: Selected Paintings 1967-77, Acme Gallery, London, UK Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, William Darby, London, UK 1979 Frank Bowling, Recent Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1980 Frank Bowling, New Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, New York, USA 1981 Frank Bowling Shilderijn, Vecu, Antwerp, Belgium 1982 Frank Bowling: Current Paintings, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, -

Dorothea Tanning

DOROTHEA TANNING Born 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois, US Died 2012 in New York, US SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Printmaker’, Farleys House & Gallery, Muddles Green, UK (forthcoming) 2020 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Worlds in Collision’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2019 Tate Modern, London, UK ‘Collection Close-Up: The Graphic Work of Dorothea Tanning’, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas, US 2018 ‘Behind the Door, Another Invisible Door’, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain 2017 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Night Shadows’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2016 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Flower Paintings’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2015 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Murmurs’, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, US 2014 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Web of Dreams’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2013 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Run: Multiples – The Printed Oeuvre’, Gallery of Surrealism, New York, US ‘Unknown But Knowable States’, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, California, US ‘Chitra Ganesh and Dorothea Tanning’, Gallery Wendi Norris at The Armory Show, New York, US 2012 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Collages’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2010 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Early Designs for the Stage’, The Drawing Center, New York, US ‘Happy Birthday, Dorothea Tanning!’, Maison Waldberg, Seillans, France ‘Zwischen dem Inneren Auge und der Anderen Seite der Tür: Dorothea Tanning Graphiken’, Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR, Brühl, Germany ‘Dorothea Tanning: 100 years – A Tribute’, Galerie Bel’Art, Stockholm, Sweden 2009 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Beyond the Esplanade -

Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-Entry Online

mM5uc (Ebook pdf) Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Online [mM5uc.ebook] Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry Pdf Free From Thames Hudson audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1211293 in Books 2015-11-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.60 x 1.20 x 9.50l, .0 #File Name: 0500093881288 pages | File size: 26.Mb From Thames Hudson : Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Derek Boshier: Rethink/Re-entry: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy DTSExcellent comprehensive monograph on the eclectic work of a significant, but overlooked contemporary artist.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Five StarsBy M S BI love everything about this collection of great art. A notable monograph on British artist Derek Boshier, covering his extensive collection of work from the mid-1950s to the present day Derek Boshierrsquo;s art has journeyed through a number of different phases, from films and painting to album covers, photography, and book making. He was a contemporary of Pauline Boty, Peter Blake, and David Hockney at the Royal College of Art and first achieved fame as part of the British Pop Art generation of the early 1960s. He then progressed to making wholly abstract illusionistic paintings with brash colors and strong patterns in shapes that broke playfully free of conventional rectangular formats. At the beginning of the 1970s, Boshier gave up painting for more than a decade and turned to book making, drawing, collage, printmaking, photography, posters, and filmmaking. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

The Economist Print Edition

The Pop master's highs and lows Nov 26th 2009 From The Economist print edition Andy Warhol is the bellwether The Andy Warhol Foundation $100m-worth of Elvises “EIGHT ELVISES” is a 12-foot painting that has all the virtues of a great Andy Warhol: fame, repetition and the threat of death. The canvas is also awash with the artist’s favourite colour, silver, and dates from a vintage Warhol year, 1963. It did not leave the home of Annibale Berlingieri, a Roman collector, for 40 years, but in autumn 2008 it sold for over $100m in a deal brokered by Philippe Ségalot, the French art consultant. That sale was a world record for Warhol and a benchmark that only four other artists—Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Gustav Klimt— have ever achieved. Warhol’s oeuvre is huge. It consists of about 10,000 artworks made between 1961, when the artist gave up graphic design, and 1987, when he died suddenly at the age of 58. Most of these are silk-screen paintings portraying anything from Campbell’s soup cans to Jackie Kennedy and Mao Zedong, drag queens and commissioning collectors. Warhol also created “disaster paintings” from newspaper clippings, as well as abstract works such as shadows and oxidations. The paintings come in series of various sizes. There are only 20 “Most Wanted Men” canvases, for example, but about 650 “Flower” paintings. Warhol also made sculpture and many experimental films, which contribute greatly to his legacy as an innovator. The Warhol market is considered the bellwether of post-war and contemporary art for many reasons, including its size and range, its emblematic transactions and the artist’s reputation as a trendsetter. -

The Ronald S. Lauder Collection Selections from the 3Rd Century Bc to the 20Th Century Germany, Austria, and France

000-000-NGRLC-JACKET_EINZEL 01.09.11 10:20 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE PRESTEL 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 2 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 3 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE With preface by Ronald S. Lauder, foreword by Renée Price, and contributions by Alessandra Comini, Stuart Pyhrr, Elizabeth Szancer Kujawski, Ann Temkin, Eugene Thaw, Christian Witt-Dörring, and William D. Wixom PRESTEL MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 4 This catalogue has been published in conjunction with the exhibition The Ronald S. Lauder Collection: Selections from the 3rd Century BC to the 20th Century. Germany, Austria, and France Neue Galerie New York, October 27, 2011 – April 2, 2012 Director of publications: Scott Gutterman Managing editor: Janis Staggs Editorial assistance: Liesbet van Leemput Curator, Ronald S . Lauder Collection: Elizabeth Szancer K ujawski Exhibition designer: Peter de Kimpe Installation: Tom Zoufaly Book design: Richard Pandiscio, William Loccisano / Pandiscio Co. Translation: Steven Lindberg Project coordination: Anja Besserer Production: Andrea Cobré Origination: royalmedia, Munich Printing and Binding: APPL aprinta, W emding for the text © Neue Galerie, New Y ork, 2011 © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New Y ork 2011 Prestel, a member of V erlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich +49 (0)89 4136-0 Tel. -

Inperson Innewyork Email Newsletter

Sign In Register You are subscribed to the Dart: Design Arts Daily inPerson inNewYork email newsletter. By Peggy Roalf Wednesday March 31, 2021 Like Share You and 2.3K others like this. Search: Most Recent: Pictoplasma #1FaceValue Daniel Bejar at Socrates Sculpture Park inPerson inNewYork Art and Design in New York The DART Board: 03.18.2021 Mark Jason Page's Workspace Archives: Friday, April 2, 6-8 pm: Owen James Gallery April 2021 March 2021 David Sandlin | Belfaust: Paintings, screenprints, books February 2021 January 2021 The artist will be in attendance at the gallery Saturday April 3rd (from 2-5 PM) to meet with visitors and December 2020 discuss his work. The following is a preview. Above: David Sandlin, Belfast Bus, acrylic on canvas. November 2020 October 2020 From the late 1960s until 1998, Northern Ireland suffered through The Troubles: an era of severe political and September 2020 sectarian violence, which was particularly brutal in the cities of Derry and Belfast. It emerged from a tormented August 2020 national history as a call for more civil rights by the area’s Catholic minority. At its heart was, and is, a bitter July 2020 debate over whether Northern Ireland should remain part of the United Kingdom or rejoin Ireland as a united June 2020 republic. Born in the late 1950s, artist David Sandlin grew up in Belfast during the 1960s and 70s, as the violence May 2020 drastically increased. Sandlin’s family was Protestant, but siblings had married into Catholic families. Due to continued threats Sandlin’s family moved to rural Alabama in the United States. -

The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds</H1>

The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds Produced by Ted Garvin, Keith M. Eckrich and PG Distributed Proofreaders THE LIFE OF MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI By JOHN ADDINGTON SYMONDS TO THE CAVALIERE GUIDO BIAGI, DOCTOR IN LETTERS, PREFECT OF THE MEDICEO-LAURENTIAN LIBRARY, ETC., ETC. I DEDICATE THIS WORK ON MICHELANGELO IN RESPECT FOR HIS SCHOLARSHIP AND LEARNING ADMIRATION OF HIS TUSCAN STYLE AND GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF HIS GENEROUS ASSISTANCE CONTENTS CHAPTER page 1 / 658 I. BIRTH, BOYHOOD, YOUTH AT FLORENCE, DOWN TO LORENZO DE' MEDICI'S DEATH. 1475-1492. II. FIRST VISITS TO BOLOGNA AND ROME--THE MADONNA DELLA FEBBRE AND OTHER WORKS IN MARBLE. 1492-1501. III. RESIDENCE IN FLORENCE--THE DAVID. 1501-1505. IV. JULIUS II. CALLS MICHELANGELO TO ROME--PROJECT FOR THE POPE'S TOMB--THE REBUILDING OF S. PETER'S--FLIGHT FROM ROME--CARTOON FOR THE BATTLE OF PISA. 1505, 1506. V. SECOND VISIT TO BOLOGNA--THE BRONZE STATUE OF JULIUS II--PAINTING OF THE SISTINE VAULT. 1506-1512. VI. ON MICHELANGELO AS DRAUGHTSMAN, PAINTER, SCULPTOR. VII. LEO X. PLANS FOR THE CHURCH OF S. LORENZO AT FLORENCE--MICHELANGELO'S LIFE AT CARRARA. 1513-1521. VIII. ADRIAN VI AND CLEMENT VII--THE SACRISTY AND LIBRARY OF S. LORENZO. 1521-1526. page 2 / 658 IX. SACK OF ROME AND SIEGE OF FLORENCE--MICHELANGELO'S FLIGHT TO VENICE--HIS RELATIONS TO THE MEDICI. 1527-1534. X. ON MICHELANGELO AS ARCHITECT. XI. FINAL SETTLEMENT IN ROME--PAUL III.--THE LAST JUDGMENT AND THE PAOLINE CHAPEL--THE TOMB OF JULIUS. -

Brice Marden Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Brice Marden Bibliography Selected Monographs and Solo Exhibition Catalogues: 2019 Brice Marden: Workbook. New York: Gagosian. 2018 Rales, Emily Wei, Ali Nemerov, and Suzanne Hudson. Brice Marden. Potomac and New York: Glenstone Museum and D.A.P. 2017 Hills, Paul, Noah Dillon, Gary Hume, Tim Marlow and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. London: Gagosian. 2016 Connors, Matt and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2015 Brice Marden: Notebook Sept. 1964–Sept.1967. New York: Karma. Brice Marden: Notebook Feb. 1968–. New York: Karma. 2013 Brice Marden: Book of Images, 1970. New York: Karma. Costello, Eileen. Brice Marden. New York: Phaidon. Galvez, Paul. Brice Marden: Graphite Drawings. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Weiss, Jeffrey, et al. Brice Marden: Red Yellow Blue. New York: Gagosian Gallery. 2012 Anfam, David. Brice Marden: Ru Ware, Marbles, Polke. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Brown, Robert. Brice Marden. Zürich: Thomas Ammann Fine Art. 2010 Weiss, Jeffrey. Brice Marden: Letters. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2008 Dannenberger, Hanne and Jörg Daur. Brice Marden – Jawlensky-Preisträger: Retrospektive der Druckgraphik. Wiesbaden: Museum Wiesbaden. Ehrenworth, Andrew, and Sonalea Shukri. Brice Marden: Prints. New York: Susan Sheehan Gallery. 2007 Müller, Christian. Brice Marden: Werke auf Papier. Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel. 2006 Garrels, Gary, Brenda Richardson, and Richard Shiff. Plane Image: A Brice Marden Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art. Liebmann, Lisa. Brice Marden: Paintings on Marble. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2003 Keller, Eva, and Regula Malin. Brice Marden. Zürich : Daros Services AG and Scalo. 2002 Duncan, Michael. Brice Marden at Gemini. -

Bleckner Biography

ROSS BLECKNER BIOGRAPHY Born in New York City, New York, 1949. Education: New York University, NYC, B.A., 1971. California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, M.F.A., 1973. Lives in New York City. Selected Solo Shows: 1983 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1986 Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1987 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1988 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1989 Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 1990 Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 1991 Kolnischer Kunstverein, Koln, Germany. Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1993 Galerie Max Hetzler, Koln, Germany. 1994 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1995 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NYC, NY. Astrup Fearnley Museet for Moderne Kunst, Oslo, Norway. I.V.A.M., Centre Julio Gonzalez, Valencia, Spain. 1996 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1997 Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, France. Bawag Foundation, Vienna, Austria. 1999 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2000 Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts. Galerie Ernst Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland. Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, England. ROSS BLECKNER BIOGRAPHY (continued) : Selected Solo Shows: 2001 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2003 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, NYC, NY. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2004 “Dialogue with Space”, Esbjerg Art Museum, Esbjerg, Denmark. 2005 Ruzicska Gallery, Salzburg, Austria. 2007 Thomas Ammann Fine Art, Zurich, Switzerland. Cais Gallery, Seoul, South Korea. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2008 “New Paintings”, Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California. 2010 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY.