'Reforming Academicians', Sculptors of the Royal Academy of Arts, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eduardo Paolozzi Born Edinburgh, Scotland. 1924 Resident London

Eduardo Paolozzi Born Edinburgh, Scotland. 1924 ResidentLondon Eduardo Paolozziwas visited in London by MT in Octo- really preparedto offer him the kind of freedom or the ber, 1968. When A & T was describedto Paolozzion degreeof accessto their personneland hardwarethat he that occasion,he respondedby expressinginterest in required--thoughthe corporation was equipped techni- working with computers. His work at that time was cally to deal with whatever demandsthe artist might involved in computer-generatedimagery, and thus it was make in the areaof computer graphics.On the evening natural that he should wish to developthese ideas. In after this encounter,Paolozzi telephoned Jane Living- Paolozzi'sletter to us of October 30, he spoke about the ston from his hotel and explainedto her that he saw no areashe visualizedpursuing: point in touring the San Josefacility or bothering It is my intention of bringing a portfolio of schemes further with lBM. Paolozzithen visited Wyle Laborator- in connection with the Los Angelesshow. These ies.He was interviewedby the company's president, schemesare an extension of work concerningimages Frank Wyle [1] ; Gail Scott wrote the following memo and words (ref: the Berkeleycatalogue; Christopher recountingthis event and later discussion: Finch's book Art and Objectsl. You may realizethat I did a certain amount of com- puter researchwhile at Berkeley,but the Art Depart- ment there was unable to extend any of these ideas- which certainly could be realizedwithin the frame- work that we discussedin London during your visit. At the moment, I have an assistantworking on colour mosaicsand endlesspermutations on the grid pattern. This is accordingto my interpretation of current computer literature and can be used in connection with sound experiments.Also the reverse,I under- stand, is possible;which is, soundscan be usedto create patterns. -

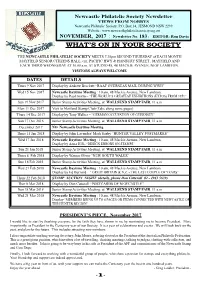

Newsletter 2017

Newcastle Philatelic Society Newsletter VIEWS FROM NOBBYS Newcastle Philatelic Society, P.O. Box 34, JESMOND NSW 2299 Website : www.newcastlephilatelicsociety.org.au NOVEMBER, 2017 : Newsletter No. 183 : EDITOR: Ron Davis WHAT’S ON IN YOUR SOCIETY THE NEWCASTLE PHILATELIC SOCIETY MEETS 7.30pm SECOND THURSDAY of EACH MONTH MAYFIELD SENIOR CITIZENS HALL, cnr, PACIFIC HWY & HANBURY STREET , MAYFIELD AND EACH THIRD WEDNESDAY AT 10.00 a.m. AT STUDIO 48, 48 MACKIE AVENUE, NEW LAMBTON. VISITORS ALWAYS WELCOME DATES DETAILS Thurs 9 Nov 2017 Display by Andrew Brockett “RAAF OVERSEAS MAIL DURING WWII” Wed 15 Nov 2017 Newcastle Daytime Meeting : 10 am, 48 Mackie Avenue, New Lambton, Display by Paul Storm – “THE WORLD’S GREATEST EXHIBITIONS (EXPOS) FROM 1851” Sun 19 Nov 2017 Junior Stamp Activities Meeting, at WALLSEND STAMP FAIR, 11 a.m Mon 11 Dec 2017 Visit to Maitland Stamp Club (Take along some pages) Thurs 14 Dec 2017 Display by Tony Walker – “GERMAN OCCUPATION OF GUERNSEY” Sun 17 Dec 2016 Junior Stamp Activities Meeting, at WALLSEND STAMP FAIR, 11 a.m December 2017 NO Newcastle Daytime Meeting Thurs 11 Jan 2018 Display by John Lavender/ Mark Saxby “HUNTER VALLEY POSTMARKS” Wed 17 Jan 2018 Newcastle Daytime Meeting : 10 am, 48 Mackie Avenue, New Lambton, Display by Anna Hill– “DESIGN ERRORS ON STAMPS” Sun 21 Jan 2018 Junior Stamp Activities Meeting, at WALLSEND STAMP FAIR, 11 a.m Thurs 8 Feb 2018 Display by Warren Oliver “NEW SOUTH WALES” Sun 18 Feb 2018 Junior Stamp Activities Meeting, at WALLSEND STAMP FAIR, 11 a.m Wed 21 Feb 2018 Newcastle Daytime Meeting : 10 am, 48 Mackie Avenue, New Lambton Display by Ed Burnard – “ GREAT BRITAIN & N,Z. -

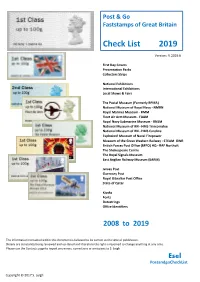

Check List 2019

Post & Go Faststamps of Great Britain Check List 2019 Version: V.2019.0 First Day Covers Presentation Packs Collectors Strips National Exhibitions International Exhibitions Local Shows & Fairs The Postal Museum (Formerly BPMA) National Museum of Royal Navy - NMRN Royal Marines Museum - RMM Fleet Air Arm Museum - FAAM Royal Navy Submarine Museum - RNSM National Museum of RN - HMS Trincomalee National Museum of RN - HMS Caroline Explosion! Museum of Naval Firepower Museum of the Great Western Railway - STEAM GWR British Forces Post Office (BFPO) HQ - RAF Northolt The Shakespeare Centre The Royal Signals Museum East Anglian Railway Museum (EARM) Jersey Post Guernsey Post Royal Gibraltar Post Office State of Qatar Kiosks Fonts Datastrings Office Identifiers 2008 to 2019 The information contained within this document is believed to be correct at the time of publication. Details are constantly being reviewed and up-dated and therefore the right is reserved to change anything at any time. Please use the Contacts page to report any errors, corrections or omissions to S. Leigh. Esel PostandgoCheckList Copyright © 2017 S. Leigh Post & Go Faststamps Esel PostandgoCheckList This Check List has been designed to only include standard issued stamps, reference is made to premature issues, major print errors and the like, but does not include all software and local print errors. Similarly, not all listings are made where, in recent times following the introduction of NCR machines, 1st and 2nd class stock are placed in the wrong printer (accidentally or intentionally) - where known they are included Also, the list does not include the Open Value (OV) Faststamps issued from NCR machines since their introduction in 2014. -

Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative : a Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Re-Shaping a First World War Narrative: A Sculptural Memorialisation Inspired by the Letters and Diaries of One New Zealand Soldier David Guerin 94114985 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Fine Arts Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand (Cover) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). (Above) Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 2/1498, New Zealand Field Artillery, First New Zealand Expeditionary Force, 1915, left, & 1917, right. 2 Dedication Dedicated to: Alfred Owen Wilkinson, 1893 ̶ 1962, 2/1498, NZFA, 1NZEF; Alexander John McKay Manson, 11/1642, MC, MiD, 1895 ̶ 1975; John Guerin, 1889 ̶ 1918, 57069, Canterbury Regiment; and Christopher Michael Guerin, 1957 ̶ 2006; And all they stood for. Alfred Owen Wilkinson, On Active Service in the Great War, Volume 1 Anzac; Volume 2 France 1916–17; Volume 3 France, Flanders, Germany (Dunedin: Self-published/A.H. Reed, 1920; 1922; 1924). 3 Acknowledgements Distinguished Professor Sally J. Morgan and Professor Kingsley Baird, thesis supervisors, for their perseverance and perspicacity, their vigilance and, most of all, their patience. With gratitude and untold thanks. All my fellow PhD candidates and staff at Whiti o Rehua/School of Arts, and Toi Rauwhārangi/ College of Creative Arts, Te Kunenga ki Pūrehuroa o Pukeahu Whanganui-a- Tara/Massey University, Wellington, especially Jess Richards. -

Film Producer Buys Seacole Bust for 101 Times the Estimate

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2454 | antiquestradegazette.com | 15 August 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Face coverings Film producer buys Seacole now mandatory at auction rooms bust for 101 times the estimate across England A terracotta sculpture of Mary Seacole by Alex Capon (1805-81) sparked fierce competition at Dominic Winter. Wearing a face covering when Bidding at the South Cerney auction house attending an auction house in England began with 12 phones competing for the has now become mandatory. sculpture of Seacole, who nursed soldiers The updated guidance also applies to visitors to galleries and museums. during the Crimean War. Since July 24, face coverings have been It eventually came down to a final contest compulsory when on public transport as involving underbidder Art Aid and film well as in supermarkets and shops including producer Billy Peterson of Racing Green dealers’ premises and antique centres. The government announced that this Pictures, which is currently filming a would be extended in England from August biopic on Seacole’s life. 8 to include other indoor spaces such as Peterson will use the bust cinemas, theatres and places of worship. as a prop in the film. It will Auction houses also appear on this list. then be donated to the The measures, brought in by law, apply Mary Seacole Trust Continued on page 5 and be on view at the Florence Nightingale Museum. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials

The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials Guidance and best practice on the understanding, assessment, planning and implementation of conservation work to war memorials as well as their ongoing maintenance and protection. www.english-heritage.org.uk/warmemorials FRONT COVER IMAGES: Top Left: Work in progress: Top Right: This differential staining Bottom Left: High pressure Bottom Right: Detail of repainted touching in lettering to enhance the is typical of exposed bronze steam cleaning (DOFF) to remove lettering; there are small holes in legibility of the names. statuary. Most of the surface has degraded wax, paint and loose the incisions that indicate that this © Humphries & Jones developed a natural patination but corrosion products, prior to was originally lead lettering. In most the original bronze colour is visible patination. cases it is recommended that re- Top Middle: The Hoylake and in protected areas. There is also © Rupert Harris Conservation Ltd lettering should follow the design West Kirby memorial has been staining from bird droppings and and nature of the original but the listed Grade II* for two main water run-off. theft of lead sometimes makes but unconnected reasons: it was © Odgers Conservation repainting an appropriate (and the first commission of Charles Consultants Ltd temporary) solution. Sargeant Jagger and it is also is © Odgers Conservation situated in a dramatic setting at Consultants Ltd the top of Grange Hill overlooking Liverpool Bay. © Peter Jackson-Lee 2008 Contents Summary 4 10 Practical -

Artwork of the Month April 2020 'Nameless and Friendless' by Emily Mary Osborn

Artwork of the Month April 2020 ‘Nameless and Friendless’ by Emily Mary Osborn (1828-1925) Small Version of ‘Nameless and Friendless’; the larger version in Tate Britain was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1857; the York version acquired 1997 with Art Fund support and a grant of £3000 from the Friends. Emily Mary Osborn (1828-1925) The origin of York Art Gallery’s collection lies in the gift in 1882 of 126 nineteenth-century (that is, at the time modern) paintings by the eccentric collector John Burton, who gives his name to the Burton Gallery; the gift included such Victorian favourites as Edward Matthew Ward’s ‘Hogarth’s Studio in 1739’. The Victorian period saw a dramatic increase in the number of registered women fine artists, from fewer than 300 in the census of 1841 to 3,700 in 1901 (for male artists the numbers are 4000 and nearly 14,000). Here Dorothy Nott, a former Chair of the Friends whose PhD at the University of York was on the work of the distinguished battle painter Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler (who incidentally narrowly missed by two votes becoming the first elected female Associate Member of the Royal Academy) writes about a remarkable small painting by a woman artist of the period in the Gallery’s collection. In 1844, when Sarah Stickney Ellis published her manual The Family Monitor and Domestic Guide, she advised her women readers not to excel at any one activity. Instead, she argued for a tolerable standard in a wide range of accomplishments. Her reasons were twofold, first, to ensure at least a basic knowledge of a variety of topics so as to facilitate social intercourse and, secondly, to prevent women from posing a threat to their male counterparts. -

The Barts Guild Calendar 2017

BBaarrttss GGuuiilldd Friends of St Bartholomew’s Hospital since 1911 OOnnee HHuunnddrreedd aanndd FFoouurrtthh AAnnnnuuaall RReeppoorrtt aanndd AAccccoouunnttss 2015-16 The Barts Guild Calendar 2017 The Guild Calendar 2017 will be on sale in the Guild Shop, KGV Building, from early October 2016; or by post at £5 plus £2.50 P&P for up to two copies (UK only), from Barts Guild Shop, King George V Building, St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London EC1A 7BE, or via the Guild website. Please send cheque with order, payable to ‘Barts Guild’ Barts Guild Friends of St Bartholomew’s Hospital since 1911 Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16 Contents The Guild of the Royal Hospital of St Bartholomew …………………………. 2 Report of the Trustees …………………………. 3 Our Corporate Supporters …………………………. 13 The Chairman writes …………………………. 14 Guild Members and Volunteers 2016 …………………………. 15 Annual General Meeting 2015 Minutes …………………………. 17 Accounts for the period 1 April 2015 – 31 March 2016 ………………………….. 21 Report of the Honorary Treasurer … 21 Independent Examiner’s Report … 22 All Funds Year ending 31 March 2016 … 23 Balance Sheet … 24 Notes to the Accounts … 25 www.bartsguild.org The Guild wishes to express grateful thanks to TFW Printers ([email protected]) for their help in producing this Annual Report Annual Report edited by Sue Boswell 1 THE GUILD OF THE ROYAL HOSPITAL OF ST BARTHOLOMEW (also known as The Barts Guild) Registered Charity No 251628 Affiliated to ATTEND – Enhancing Health and Social Care. Locally PATRON OFFICERS OF THE GUILD 2015-16 HRH The Duke -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Roland Piché ARCA FRBS Born 1938, London Art Education 1956-60 Hornsey College of Art Worked with sculptor Gaudia in Canada 1960-64 Royal College of Art 1963-64 Part-time assistant to Henry Moore Teaching Experience Slade School of Art Royal College of Art Central School of Art Falmouth School of Art Gloucestershire College of Art & Design Chelsea School of Art Birmingham Polytechnic Lancaster Polytechnic Manchester Polytechnic Goldsmiths College of Art Loughborough College of Art Newcastle upon Tyne Polytechnic Newport College of Art & Design North Staffordshire Polytechnic Stourbridge College of Art Trent Polytechnic West Surrey College of Art Wolverhampton Polytechnic Edinburgh School of Art Bristol Polytechnic (Sculpture) Leicester Polytechnic (Sculpture) 1964-89 Principal Lecturer, in charge of Sculpture, Maidstone College of Art Subject Leader, Sculpture, School of Fine Art, Kent Institute of Art & Design, Canterbury One Person Exhibitions 1967 Marlborough New London Gallery 1969 Gallery Ad Libitum, Antwerp B Middelheim Biennale, Antwerp B 1975 Canon Park, Birmingham 1980 The Ikon Gallery, Birmingham Minories Galleries, Colchester "Spaceframes & Circles" 1993 Kopp-Bardellini Agent Gallery, Zurich CH 2001 Glaxo Smith Kline - Harlow Research Centre 2005 Chappel Galleries, Essex 2010 Time & Life Building, London Group Exhibitions 1962 Towards Art I, Royal College of Art 1963-4 Young Contemporaries, AID Gallery 1964 Young Contemporary Artists, Whitechapel Gallery Maidstone College of Art Students, Show New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone 1965 Towards Art II, Royal College of Art, Sculpture at the Arts Council The New Generation, 1965, Whitechapel Gallery Whitworth Art Gallery Manchester Summer Exhibition Marlborough New London Gallery 4th Biennale de Paris 1966 The English Eye, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York Structure 66, Arts Council of Gt. -

Collecting in the 20Th Century

The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art - Yale University November 2007 Issue 25 newsletter A Passion for British Art: Collecting in the 20th Century Friday 18 January 2008 The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art J. M. W. Turner, “Dort, Dordrecht: The Dort Packet-Boat from Rotterdam Becalmed,” 1817-18, oil on canvas,Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection This one-day conference to be held at the assembled in the twentieth century. Although it Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, encompasses works from many periods and will discuss issues related to the collection of cultures, at the heart of the Mellon collection the late Paul Mellon (1907-1999), and the are pictures from the ‘Golden Age’ of British art, exhibition, ‘An American’s Passion for British from the mid-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth Art, Paul Mellon’s Legacy’, at the Royal Academy century. Among modern private collectors, of Arts, London (20 October 2007 - 27 January however, Mr Mellon was not alone in his 2008). Paul Mellon’s collection, which embraces appreciation of the merits of the British School, paintings, watercolours, drawings, prints, and this conference aims to set his achievement sculptures, rare books and manuscripts is within the global context of modern and among the finest of its kind to have been contemporary collecting. 16 Bedford Square London WC1B 3JA Tel: 020 7580 0311 Fax: 020 7636 6730 www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk Paul Mellon Centre conference A Passion for British Art: Collecting in the 20th Century Friday 18 January 2008, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art Conference Programme Morning session to be chaired by Professor Brian Allen (Director of Studies, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art). -

Parish Magazine November 2017

NOV& DEC 2017 Spire & Tower St Andrew & St Mark £1.00 Church Magazine A CHURCH MAGAZINE BRINGING YOU ALL OUR NEWS & WORK FROM AROUND SURBITON www.surbitonchurch.org.uk CONTENTS NOV & DEC 3- A VIEW FROM THE VICAR 4- 6 REMEMBRANCE OF THE GREAT WAR 7- MOTHERS’ UNION 8- PAST TIMES OF SURBITON Pg.3 A View from the Vicar 9- OUTSIDE THE BOUNDARIES 10-11 FLYING CIRCUS TO DORICH HOUSE 12-16 A VERY WARM THANK YOU 17 The CHRISTMAS DAY PARTY 18-19 SO WHO ARE STREET PASTORS? 20-21 GARDNER'S CORNER Pg. 4-6 Remembrance of the Great War Pg. 32-33 22-23 SASM CHILDREN’S CORNER Memoriesa of 24-26 HAVE YOU EVER WASSAILED? Surbitonian 27-31 PERSONAL THOUGHTS ON OUR IONIAN PILGRIMAGE 32-33 PART 3 KEITH KIRBY FRONT COVER 34- BOOK REVIEW 35-38 ADVERTS & COMING UP IN THE NEXT EDITION Image taken from: 39- IN FLANDERS FIELD www.rustusovka.com 40- SERVICE CALENDER 41- MINISTRY STAFF TEAM 42-43 CHILDREN’S COLOURING PAGE I very much regret that in the last edition we inserted the incorrect names for Audrey & Ken Peay on pages 32 & 33. The online version of the magazine has been corrected. Editor www.surbitonchurch.org.uk 2 A VIEW FROM THE VICAR As I write this, today’s newspapers are full of lurid stories about Harvey Weinstein, the hitherto respected Hollywood producer who, it turns out, got sexual kicks from inviting young actresses to his hotel room and asking them to give him sexual favours of one kind or another.