Oral History of John Backus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspective and Further Reading 162.E1

2.21 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 162.e1 2.21 Historical Perspective and Further Reading Th is section surveys the history of in struction set architectures over time, and we give a short history of programming languages and compilers. ISAs include accumulator architectures, general-purpose register architectures, stack architectures, and a brief history of ARMv7 and the x86. We also review the controversial subjects of high-level-language computer architectures and reduced instruction set computer architectures. Th e history of programming languages includes Fortran, Lisp, Algol, C, Cobol, Pascal, Simula, Smalltalk, C+ + , and Java, and the history of compilers includes the key milestones and the pioneers who achieved them. Accumulator Architectures Hardware was precious in the earliest stored-program computers. Consequently, computer pioneers could not aff ord the number of registers found in today’s architectures. In fact, these architectures had a single register for arithmetic instructions. Since all operations would accumulate in one register, it was called the accumulator , and this style of instruction set is given the same name. For example, accumulator Archaic EDSAC in 1949 had a single accumulator. term for register. On-line Th e three-operand format of RISC-V suggests that a single register is at least two use of it as a synonym for registers shy of our needs. Having the accumulator as both a source operand and “register” is a fairly reliable indication that the user the destination of the operation fi lls part of the shortfall, but it still leaves us one has been around quite a operand short. Th at fi nal operand is found in memory. -

John Mccarthy

JOHN MCCARTHY: the uncommon logician of common sense Excerpt from Out of their Minds: the lives and discoveries of 15 great computer scientists by Dennis Shasha and Cathy Lazere, Copernicus Press August 23, 2004 If you want the computer to have general intelligence, the outer structure has to be common sense knowledge and reasoning. — John McCarthy When a five-year old receives a plastic toy car, she soon pushes it and beeps the horn. She realizes that she shouldn’t roll it on the dining room table or bounce it on the floor or land it on her little brother’s head. When she returns from school, she expects to find her car in more or less the same place she last put it, because she put it outside her baby brother’s reach. The reasoning is so simple that any five-year old child can understand it, yet most computers can’t. Part of the computer’s problem has to do with its lack of knowledge about day-to-day social conventions that the five-year old has learned from her parents, such as don’t scratch the furniture and don’t injure little brothers. Another part of the problem has to do with a computer’s inability to reason as we do daily, a type of reasoning that’s foreign to conventional logic and therefore to the thinking of the average computer programmer. Conventional logic uses a form of reasoning known as deduction. Deduction permits us to conclude from statements such as “All unemployed actors are waiters, ” and “ Sebastian is an unemployed actor,” the new statement that “Sebastian is a waiter.” The main virtue of deduction is that it is “sound” — if the premises hold, then so will the conclusions. -

John Mccarthy – Father of Artificial Intelligence

Asia Pacific Mathematics Newsletter John McCarthy – Father of Artificial Intelligence V Rajaraman Introduction I first met John McCarthy when he visited IIT, Kanpur, in 1968. During his visit he saw that our computer centre, which I was heading, had two batch processing second generation computers — an IBM 7044/1401 and an IBM 1620, both of them were being used for “production jobs”. IBM 1620 was used primarily to teach programming to all students of IIT and IBM 7044/1401 was used by research students and faculty besides a large number of guest users from several neighbouring universities and research laboratories. There was no interactive computer available for computer science and electrical engineering students to do hardware and software research. McCarthy was a great believer in the power of time-sharing computers. John McCarthy In fact one of his first important contributions was a memo he wrote in 1957 urging the Director of the MIT In this article we summarise the contributions of Computer Centre to modify the IBM 704 into a time- John McCarthy to Computer Science. Among his sharing machine [1]. He later persuaded Digital Equip- contributions are: suggesting that the best method ment Corporation (who made the first mini computers of using computers is in an interactive mode, a mode and the PDP series of computers) to design a mini in which computers become partners of users computer with a time-sharing operating system. enabling them to solve problems. This logically led to the idea of time-sharing of large computers by many users and computing becoming a utility — much like a power utility. -

Fpgas As Components in Heterogeneous HPC Systems: Raising the Abstraction Level of Heterogeneous Programming

FPGAs as Components in Heterogeneous HPC Systems: Raising the Abstraction Level of Heterogeneous Programming Wim Vanderbauwhede School of Computing Science University of Glasgow A trip down memory lane 80 Years ago: The Theory Turing, Alan Mathison. "On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem." J. of Math 58, no. 345-363 (1936): 5. 1936: Universal machine (Alan Turing) 1936: Lambda calculus (Alonzo Church) 1936: Stored-program concept (Konrad Zuse) 1937: Church-Turing thesis 1945: The Von Neumann architecture Church, Alonzo. "A set of postulates for the foundation of logic." Annals of mathematics (1932): 346-366. 60-40 Years ago: The Foundations The first working integrated circuit, 1958. © Texas Instruments. 1957: Fortran, John Backus, IBM 1958: First IC, Jack Kilby, Texas Instruments 1965: Moore’s law 1971: First microprocessor, Texas Instruments 1972: C, Dennis Ritchie, Bell Labs 1977: Fortran-77 1977: von Neumann bottleneck, John Backus 30 Years ago: HDLs and FPGAs Algotronix CAL1024 FPGA, 1989. © Algotronix 1984: Verilog 1984: First reprogrammable logic device, Altera 1985: First FPGA,Xilinx 1987: VHDL Standard IEEE 1076-1987 1989: Algotronix CAL1024, the first FPGA to offer random access to its control memory 20 Years ago: High-level Synthesis Page, Ian. "Closing the gap between hardware and software: hardware-software cosynthesis at Oxford." (1996): 2-2. 1996: Handel-C, Oxford University 2001: Mitrion-C, Mitrionics 2003: Bluespec, MIT 2003: MaxJ, Maxeler Technologies 2003: Impulse-C, Impulse Accelerated -

The History of Computer Language Selection

The History of Computer Language Selection Kevin R. Parker College of Business, Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho USA [email protected] Bill Davey School of Business Information Technology, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract: This examines the history of computer language choice for both industry use and university programming courses. The study considers events in two developed countries and reveals themes that may be common in the language selection history of other developed nations. History shows a set of recurring problems for those involved in choosing languages. This study shows that those involved in the selection process can be informed by history when making those decisions. Keywords: selection of programming languages, pragmatic approach to selection, pedagogical approach to selection. 1. Introduction The history of computing is often expressed in terms of significant hardware developments. Both the United States and Australia made early contributions in computing. Many trace the dawn of the history of programmable computers to Eckert and Mauchly’s departure from the ENIAC project to start the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation. In Australia, the history of programmable computers starts with CSIRAC, the fourth programmable computer in the world that ran its first test program in 1949. This computer, manufactured by the government science organization (CSIRO), was used into the 1960s as a working machine at the University of Melbourne and still exists as a complete unit at the Museum of Victoria in Melbourne. Australia’s early entry into computing makes a comparison with the United States interesting. These early computers needed programmers, that is, people with the expertise to convert a problem into a mathematical representation directly executable by the computer. -

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory

The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Eamonn Bell All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Computational Attitude in Music Theory Eamonn Bell Music studies’s turn to computation during the twentieth century has engendered particular habits of thought about music, habits that remain in operation long after the music scholar has stepped away from the computer. The computational attitude is a way of thinking about music that is learned at the computer but can be applied away from it. It may be manifest in actual computer use, or in invocations of computationalism, a theory of mind whose influence on twentieth-century music theory is palpable. It may also be manifest in more informal discussions about music, which make liberal use of computational metaphors. In Chapter 1, I describe this attitude, the stakes for considering the computer as one of its instruments, and the kinds of historical sources and methodologies we might draw on to chart its ascendance. The remainder of this dissertation considers distinct and varied cases from the mid-twentieth century in which computers or computationalist musical ideas were used to pursue new musical objects, to quantify and classify musical scores as data, and to instantiate a generally music-structuralist mode of analysis. I present an account of the decades-long effort to prepare an exhaustive and accurate catalog of the all-interval twelve-tone series (Chapter 2). This problem was first posed in the 1920s but was not solved until 1959, when the composer Hanns Jelinek collaborated with the computer engineer Heinz Zemanek to jointly develop and run a computer program. -

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages Lecture 1 - An Introduction What is a Programming Language? • A programming language is a notational system for describing computation in machine-readable and human-readable form. • Most of these forms are high-level languages , which is the subject of the course. • Assembly languages and other languages that are designed to more closely resemble the computer’s instruction set than anything that is human- readable are low-level languages . Why Study Programming Languages? • In 1969, Sammet listed 120 programming languages in common use – now there are many more! • Most programmers never use more than a few. – Some limit their career’s to just one or two. • The gain is in learning about their underlying design concepts and how this affects their implementation. The Six Primary Reasons • Increased ability to express ideas • Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Increased ability to learn new languages • Better understanding of significance of implementation • Better use of languages that are already known • Overall advancement of computing Reason #1 - Increased ability to express ideas • The depth at which people can think is heavily influenced by the expressive power of their language. • It is difficult for people to conceptualize structures that they cannot describe, verbally or in writing. Expressing Ideas as Algorithms • This includes a programmer’s to develop effective algorithms • Many languages provide features that can waste computer time or lead programmers to logic errors if used improperly – E. g., recursion in Pascal, C, etc. – E. g., GoTos in FORTRAN, etc. Reason #2 - Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Many professional programmers have a limited formal education in computer science, limited to a small number of programming languages. -

Evolution of the Major Programming Languages

COS 301 Programming Languages Evolution of the Major Programming Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics Zuse’s Plankalkül Minimal Hardware Programming: Pseudocodes The IBM 704 and Fortran Functional Programming: LISP ALGOL 60 COBOL BASIC PL/I APL and SNOBOL SIMULA 67 Orthogonal Design: ALGOL 68 UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics (continued) Some Early Descendants of the ALGOLs Prolog Ada Object-Oriented Programming: Smalltalk Combining Imperative and Object-Oriented Features: C++ Imperative-Based Object-Oriented Language: Java Scripting Languages A C-Based Language for the New Millennium: C# Markup/Programming Hybrid Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Genealogy of Common Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Alternate View UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Zuse’s Plankalkül • Designed in 1945 • For computers based on electromechanical relays • Not published until 1972, implemented in 2000 [Rojas et al.] • Advanced data structures: – Two’s complement integers, floating point with hidden bit, arrays, records – Basic data type: arrays, tuples of arrays • Included algorithms for playing chess • Odd: 2D language • Functions, but no recursion • Loops (“while”) and guarded conditionals [Dijkstra, 1975] UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Plankalkül Syntax • 3 lines for a statement: – Operation – Subscripts – Types • An assignment -

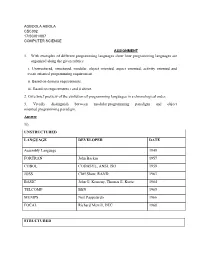

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Pioneers of Computing

Pioneers of Computing В 1980 IEEE Computer Society учредило Золотую медаль (бронзовую) «Вычислительный Пионер» Пионерами учредителями стали 32 члена IEEE Computer Society, связанных с работами по информатике и вычислительным наукам. 1 Pioneers of Computing 1.Howard H. Aiken (Havard Mark I) 2.John V. Atanasoff 3.Charles Babbage (Analytical Engine) 4.John Backus 5.Gordon Bell (Digital) 6.Vannevar Bush 7.Edsger W. Dijkstra 8.John Presper Eckert 9.Douglas C. Engelbart 10.Andrei P. Ershov (theroretical programming) 11.Tommy Flowers (Colossus engineer) 12.Robert W. Floyd 13.Kurt Gödel 14.William R. Hewlett 15.Herman Hollerith 16.Grace M. Hopper 17.Tom Kilburn (Manchester) 2 Pioneers of Computing 1. Donald E. Knuth (TeX) 2. Sergei A. Lebedev 3. Augusta Ada Lovelace 4. Aleksey A.Lyapunov 5. Benoit Mandelbrot 6. John W. Mauchly 7. David Packard 8. Blaise Pascal 9. P. Georg and Edvard Scheutz (Difference Engine, Sweden) 10. C. E. Shannon (information theory) 11. George R. Stibitz 12. Alan M. Turing (Colossus and code-breaking) 13. John von Neumann 14. Maurice V. Wilkes (EDSAC) 15. J.H. Wilkinson (numerical analysis) 16. Freddie C. Williams 17. Niklaus Wirth 18. Stephen Wolfram (Mathematica) 19. Konrad Zuse 3 Pioneers of Computing - 2 Howard H. Aiken (Havard Mark I) – США Создатель первой ЭВМ – 1943 г. Gene M. Amdahl (IBM360 computer architecture, including pipelining, instruction look-ahead, and cache memory) – США (1964 г.) Идеология майнфреймов – система массовой обработки данных John W. Backus (Fortran) – первый язык высокого уровня – 1956 г. 4 Pioneers of Computing - 3 Robert S. Barton For his outstanding contributions in basing the design of computing systems on the hierarchical nature of programs and their data. -

Publications Core Magazine, 2007 Read

CA PUBLICATIONo OF THE COMPUTERre HISTORY MUSEUM ⁄⁄ SPRINg–SUMMER 2007 REMARKABLE PEOPLE R E scuE d TREAsuREs A collection saved by SAP Focus on E x TRAORdinARy i MAGEs Computers through the Robert Noyce lens of Mark Richards PUBLISHER & Ed I t o R - I n - c hie f THE BEST WAY Karen M. Tucker E X E c U t I V E E d I t o R TO SEE THE FUTURE Leonard J. Shustek M A n A GI n G E d I t o R OF COMPUTING IS Robert S. Stetson A S S o c IA t E E d I t o R TO BROWSE ITS PAST. Kirsten Tashev t E c H n I c A L E d I t o R Dag Spicer E d I t o R Laurie Putnam c o n t RIBU t o RS Leslie Berlin Chris garcia Paula Jabloner Luanne Johnson Len Shustek Dag Spicer Kirsten Tashev d E S IG n Kerry Conboy P R o d U c t I o n ma n ager Robert S. Stetson W E BSI t E M A n AGER Bob Sanguedolce W E BSI t E d ESIG n The computer. In all of human history, rarely has one invention done Dana Chrisler so much to change the world in such a short time. Ton Luong The Computer History Museum is home to the world’s largest collection computerhistory.org/core of computing artifacts and offers a variety of exhibits, programs, and © 2007 Computer History Museum. -

Creativity in Computer Science. in J

Creativity in Computer Science Daniel Saunders and Paul Thagard University of Waterloo Saunders, D., & Thagard, P. (forthcoming). Creativity in computer science. In J. C. Kaufman & J. Baer (Eds.), Creativity across domains: Faces of the muse. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1. Introduction Computer science only became established as a field in the 1950s, growing out of theoretical and practical research begun in the previous two decades. The field has exhibited immense creativity, ranging from innovative hardware such as the early mainframes to software breakthroughs such as programming languages and the Internet. Martin Gardner worried that "it would be a sad day if human beings, adjusting to the Computer Revolution, became so intellectually lazy that they lost their power of creative thinking" (Gardner, 1978, p. vi-viii). On the contrary, computers and the theory of computation have provided great opportunities for creative work. This chapter examines several key aspects of creativity in computer science, beginning with the question of how problems arise in computer science. We then discuss the use of analogies in solving key problems in the history of computer science. Our discussion in these sections is based on historical examples, but the following sections discuss the nature of creativity using information from a contemporary source, a set of interviews with practicing computer scientists collected by the Association of Computing Machinery’s on-line student magazine, Crossroads. We then provide a general comparison of creativity in computer science and in the natural sciences. 2. Nature and Origins of Problems in Computer Science December 21, 2004 Computer science is closely related to both mathematics and engineering.