John Backus (1924–2007) Inventor of Science’S Most Widespread Programming Language, Fortran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Computer Language Selection

The History of Computer Language Selection Kevin R. Parker College of Business, Idaho State University, Pocatello, Idaho USA [email protected] Bill Davey School of Business Information Technology, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia [email protected] Abstract: This examines the history of computer language choice for both industry use and university programming courses. The study considers events in two developed countries and reveals themes that may be common in the language selection history of other developed nations. History shows a set of recurring problems for those involved in choosing languages. This study shows that those involved in the selection process can be informed by history when making those decisions. Keywords: selection of programming languages, pragmatic approach to selection, pedagogical approach to selection. 1. Introduction The history of computing is often expressed in terms of significant hardware developments. Both the United States and Australia made early contributions in computing. Many trace the dawn of the history of programmable computers to Eckert and Mauchly’s departure from the ENIAC project to start the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation. In Australia, the history of programmable computers starts with CSIRAC, the fourth programmable computer in the world that ran its first test program in 1949. This computer, manufactured by the government science organization (CSIRO), was used into the 1960s as a working machine at the University of Melbourne and still exists as a complete unit at the Museum of Victoria in Melbourne. Australia’s early entry into computing makes a comparison with the United States interesting. These early computers needed programmers, that is, people with the expertise to convert a problem into a mathematical representation directly executable by the computer. -

Proceedings of the Rexx Symposium for Developers and Users

SLAC-R-95-464 CONF-9505198-- PROCEEDINGS OF THE REXX SYMPOSIUM FOR DEVELOPERS AND USERS May 1-3,1995 Stanford, California Convened by STANFORD LINEAR ACCELERATOR CENTER STANFORD UNIVERSITY, STANFORD, CALIFORNIA 94309 Program Committee Cathie Dager of SLAC, Convener Forrest Garnett of IBM Pam Taylor of The Workstation Group James Weissman Prepared for the Department of Energy under Contract number DE-AC03-76SF00515 Printed in the United States of America. Available from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22161. DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IS UNLIMITED ;--. i*-„r> ->&• DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. DISCLAIMER Portions -

Z/OS Resilience Enhancements

17118: z/OS Resilience Enhancements Harry Yudenfriend IBM Fellow, Storage Development March 3, 2015 Insert Custom Session QR if Desired. Agenda • Review strategy for improving SAN resilience • Details of z/OS 1.13 Enhancements • Enhancements for 2014 Session 16896: IBM z13 and DS8870 I/O Innovations for z Systems for additional information on z/OS resilience enhancements. © 2015 IBM Corporation 3 SAN Resilience Strategy • Clients should consider exploiting technologies to improve SAN resilience – Quick detection of errors – First failure data capture – Automatically identify route cause and failing component – Minimize impact on production work by fencing the failing resources quickly – Prevent errors from impacting production work by identifying problem links © 2015 IBM Corporation 4 FICON Enterprise QoS • Tight timeouts for quicker recognition of lost frames and more responsive recovery • Differentiate between lost frames and congestion • Explicit notification of SAN fabric issues • End-to-End Data integrity checking transparent to applications and middleware • In-band instrumentation to enable – SAN health checks – Smart channel path selection – Work Load Management – Autonomic identification of faulty SAN components with Purge-Path-Extended – Capacity planning – Problem determination – Identification of Single Points of Failure – Real time configuration checking with reset event and self description • No partially updated records in the presence of a failure • Proactive identification of faulty links via Link Incident Reporting • Integrated management software for safe switching for z/OS and storage • High Integrity, High Security Fabric © 2015 IBM Corporation 5 System z Technology Summary • Pre-2013 Items a) IOS Recovery option: RECOVERY,LIMITED_RECTIME b) z/OS 1.13 I/O error thresholds and recovery aggregation c) z/OS message to identify failing link based on LESB data d) HCD Generation of CONFIGxx member with D M=CONFIG(xx) e) Purge Path Extended (LESB data to SYS1.LOGREC) f) zHPF Read Exchange Concise g) CMR time to differentiate between congestion vs. -

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages

CSC 272 - Software II: Principles of Programming Languages Lecture 1 - An Introduction What is a Programming Language? • A programming language is a notational system for describing computation in machine-readable and human-readable form. • Most of these forms are high-level languages , which is the subject of the course. • Assembly languages and other languages that are designed to more closely resemble the computer’s instruction set than anything that is human- readable are low-level languages . Why Study Programming Languages? • In 1969, Sammet listed 120 programming languages in common use – now there are many more! • Most programmers never use more than a few. – Some limit their career’s to just one or two. • The gain is in learning about their underlying design concepts and how this affects their implementation. The Six Primary Reasons • Increased ability to express ideas • Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Increased ability to learn new languages • Better understanding of significance of implementation • Better use of languages that are already known • Overall advancement of computing Reason #1 - Increased ability to express ideas • The depth at which people can think is heavily influenced by the expressive power of their language. • It is difficult for people to conceptualize structures that they cannot describe, verbally or in writing. Expressing Ideas as Algorithms • This includes a programmer’s to develop effective algorithms • Many languages provide features that can waste computer time or lead programmers to logic errors if used improperly – E. g., recursion in Pascal, C, etc. – E. g., GoTos in FORTRAN, etc. Reason #2 - Improved background for choosing appropriate languages • Many professional programmers have a limited formal education in computer science, limited to a small number of programming languages. -

Evolution of the Major Programming Languages

COS 301 Programming Languages Evolution of the Major Programming Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics Zuse’s Plankalkül Minimal Hardware Programming: Pseudocodes The IBM 704 and Fortran Functional Programming: LISP ALGOL 60 COBOL BASIC PL/I APL and SNOBOL SIMULA 67 Orthogonal Design: ALGOL 68 UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Topics (continued) Some Early Descendants of the ALGOLs Prolog Ada Object-Oriented Programming: Smalltalk Combining Imperative and Object-Oriented Features: C++ Imperative-Based Object-Oriented Language: Java Scripting Languages A C-Based Language for the New Millennium: C# Markup/Programming Hybrid Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Genealogy of Common Languages UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Alternate View UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Zuse’s Plankalkül • Designed in 1945 • For computers based on electromechanical relays • Not published until 1972, implemented in 2000 [Rojas et al.] • Advanced data structures: – Two’s complement integers, floating point with hidden bit, arrays, records – Basic data type: arrays, tuples of arrays • Included algorithms for playing chess • Odd: 2D language • Functions, but no recursion • Loops (“while”) and guarded conditionals [Dijkstra, 1975] UMaine School of Computing and Information Science COS 301 - 2018 Plankalkül Syntax • 3 lines for a statement: – Operation – Subscripts – Types • An assignment -

CS406: Compilers Spring 2020

CS406: Compilers Spring 2020 Week1: Overview, Structure of a compiler 1 1 Intro to Compilers • Way to implement programming languages • Programming languages are notations for specifying computations to machines Program Compiler Target • Target can be an assembly code, executable, another source program etc. 2 2 What is a Compiler? Traditionally: Program that analyzes and translates from a high-level language (e.g. C++) to low-level assembly language that can be executed by the hardware var a var b int a, b; mov 3 a a = 3; mov 4 r1 if (a < 4) { cmpi a r1 b = 2; jge l_e } else { mov 2 b b = 3; jmp l_d } l_e:mov 3 b l_d:;done 3 slide courtesy: Milind Kulkarni 3 Compilers are translators •Fortran •C ▪Machine code •C++ ▪Virtual machine code •Java ▪Transformed source •Text processing translate code language ▪Augmented source •HTML/XML code •Command & ▪Low-level commands Scripting ▪Semantic components Languages ▪Another language •Natural Language •Domain Specific Language 4 slide courtesy: Milind Kulkarni 4 Compilers are optimizers • Can perform optimizations to make a program more efficient var a var b var a int a, b, c; var c var b b = a + 3; mov a r1 var c c = a + 3; addi 3 r1 mov a r1 mov r1 b addi 3 r1 mov a r2 mov r1 b addi 3 r2 mov r1 c mov r2 c 5 slide courtesy: Milind Kulkarni 5 Why do we need compilers? • Compilers provide portability • Old days: whenever a new machine was built, programs had to be rewritten to support new instruction sets • IBM System/360 (1964): Common Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) --- programs could be run -

Object Orientation Through the Lens of Computer Science Education with Some New Implications from Other Subjects Like the Humanities

Technische Universität München Fakultät für Informatik Fachgebiet Didaktik der Informatik Object-Oriented Programming through the Lens of Computer Science Education Marc-Pascal Berges Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Informatik der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Johann Schlichter Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Hubwieser 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Torsten Brinda, Universität Duisburg-Essen Die Dissertation wurde am 07. April 2015 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Informatik am 02. Juli 2015 angenommen. Abstract In recent years, the importance of the object-oriented paradigm has changed signifi- cantly. Initially it was mainly used in software engineering, but it is now being used more and more in education. This thesis applies methods of educational assessment and statistics to object-oriented programming and in doing so provides a broad overview of concepts, teaching methods, and the current state of research in this field of computer science. Recently, there have been various trends in introductory courses for object-oriented programming including objects-first and objects-later. Using current pedagogical concepts such as cognitive load theory, conceptual change, and self-directed learning in the context of this work, a teaching approach that dispenses almost entirely of instruction by teachers was developed. These minimally invasive programming courses (MIPC) were carried out in several passes in preliminary courses in the Department of Computer Science at the TU München. The students were confronted with a small programming task just before the first lecture. -

Programming Languages: Lecture 2

1 Programming Languages: Lecture 2 Chapter 2: Evolution of the Major Programming Languages Jinwoo Kim [email protected] 2 Chapter 2 Topics • History of Computers • Zuse’s Plankalkul • Minimal Hardware Programming: Pseudocodes • The IBM 704 and Fortran • Functional Programming: LISP • The First Step Toward Sophistication: ALGOL 60 • Computerizing Business Records: COBOL • The Beginnings of Timesharing: BASIC 3 Chapter 2 Topics (continued) • Everything for Everybody: PL/I • Two Early Dynamic Languages: APL and SNOBOL • The Beginnings of Data Abstraction: SIMULA 67 • Orthogonal Design: ALGOL 68 • Some Early Descendants of the ALGOLs • Programming Based on Logic: Prolog • History's Largest Design Effort: Ada 4 Chapter 2 Topics (continued) • Object-Oriented Programming: Smalltalk • Combining Imperative ad Object-Oriented Features: C++ • An Imperative-Based Object-Oriented Language: Java • Scripting Languages: JavaScript, PHP, Python, and Ruby • A C-Based Language for the New Millennium: C# • Markup/Programming Hybrid Languages 5 History of Computers • Who invented computers? – Contribution from many inventors – A computer is a complex piece of machinery made up of many parts, each of which can be considered a separate invention. • In 1936, Konrad Zuse made a mechanical calculator using three basic elements: a control, a memory, and a calculator for the arithmetic and called it Z1, the first binary computer – First freely programmable computer – Konrad Zuse wrote the first algorithmic programming language called 'Plankalkül' in 1946, which -

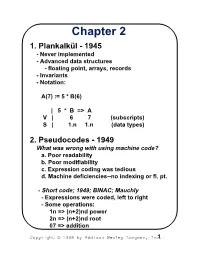

Evolution of the Major Programming Languages

Chapter 2 1. Plankalkül - 1945 - Never implemented - Advanced data structures - floating point, arrays, records - Invariants - Notation: A(7) := 5 * B(6) | 5 * B => A V | 6 7 (subscripts) S | 1.n 1.n (data types) 2. Pseudocodes - 1949 What was wrong with using machine code? a. Poor readability b. Poor modifiability c. Expression coding was tedious d. Machine deficiencies--no indexing or fl. pt. - Short code; 1949; BINAC; Mauchly - Expressions were coded, left to right - Some operations: 1n => (n+2)nd power 2n => (n+2)nd root 07 => addition Copyright © 1998 by Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.1 Chapter 2 2. Pseudocodes (continued) - Speedcoding; 1954; IBM 701, Backus - Pseudo ops for arithmetic and math functions - Conditional and unconditional branching - Autoincrement registers for array access - Slow! - Only 700 words left for user program 3. Laning and Zierler System - 1953 - Implemented on the MIT Whirlwind computer - First "algebraic" compiler system - Subscripted variables, function calls, expression translation - Never ported to any other machine 4. FORTRAN I - 1957 (FORTRAN 0 - 1954 - not implemented) - Designed for the new IBM 704, which had index registers and floating point hardware - Environment of development: 1. Computers were small and unreliable 2. Applications were scientific 3. No programming methodology or tools 4. Machine efficiency was most important Copyright © 1998 by Addison Wesley Longman, Inc.2 Chapter 2 4. FORTRAN I (continued) - Impact of environment on design 1. No need for dynamic storage 2. Need good array handling -

Speaker Bios

SPEAKER BIOS Speaker: Nilanjan Banerjee, Associate Professor, Computer Science & Electrical Engineering, UMBC Topic: Internet of Things/Cyber-Physical Systems Nilanjan Banerjee is an Associate Professor at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. He is an expert in mobile and sensor systems with focus on designing end-to-end cyber-physical systems with applications to physical rehabilitation, physiological monitoring, and home energy management systems. He holds a Ph.D. and a M.S. in Computer Science from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a BTech. (Hons.) from Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur. Speaker: Keith Bowman, Dean, College of Engineering & Information Technology (COEIT), UMBC Topics: Welcoming Remarks and Farewell and Wrap Keith J. Bowman has begun his tenure as the new dean of UMBC’s College of Engineering and Information Technology (COEIT). He joined UMBC on August 1, 2017, from San Francisco State University in California, where he served as dean of the College of Science and Engineering since 2015. Bowman holds a Ph.D. in materials science from the University of Michigan, and B.S. and M.S. degrees in materials science from Case Western Reserve University. Prior to his role at SFSU, he held various positions at the Illinois Institute of Technology and Purdue University. At the Illinois Institute of Technology, he was the Duchossois Leadership Professor and chair of mechanical, materials, and aerospace engineering. In Purdue University’s School of Materials Engineering, he served as a professor and head of the school. He also held visiting professorships at the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany and at the University of New South Wales in Australia. -

CSE452 Fall2004 (Cheng)

CSE452 Fall2004 (Cheng) Organization of Programming Languages (CSE452) Instructor: Dr. B. Cheng Fall 2004 Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 1 Evolution of Programming Languages ? Purpose: to give perspective of: ? where we’ve been, ? where we are, and ? where we might be going. ? Take away the mystery behind programming languages ? Fun lecture. ? Acknowledgements: R. Sebesta Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 2 Genealogy of Common Languages Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 3 1 CSE452 Fall2004 (Cheng) History of Programming Languages http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/P/programming_language.html Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 4 Zuse’s Plankalkül - 1945 ? Never implemented ? Advanced data structures ? floating point, arrays, records ? Invariants Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 5 Evolution of software architecture ? 1950s - Large expensive mainframe computers ran single programs (Batch processing) ? 1960s - Interactive programming (time-sharing) on mainframes ? 1970s - Development of Minicomputers and first microcomputers. Apple II. Early work on windows, icons, and PCs at XEROX PARC ? 1980s - Personal computer - Microprocessor, IBM PC and Apple Macintosh. Use of windows, icons and mouse ? 1990s - Client-server computing - Networking, The Internet, the World Wide Web Organization of Programming Languages-Cheng (Fall 2004) 6 2 CSE452 Fall2004 (Cheng) Pseudocodes - 1949 ? What was wrong with using machine code? ? Poor readability ? -

Programming in America in the 1950S- Some Personal Impressions

A HISTORY OF COMPUTING IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Programming in America in the 1950s- Some Personal Impressions * JOHN BACKUS 1. Introduction The subject of software history is a complex one in which authoritative information is scarce. Furthermore, it is difficult for anyone who has been an active participant to give an unbiased assessment of his area of interest. Thus, one can find accounts of early software development that strive to ap- pear objective, and yet the importance and priority claims of the author's own work emerge rather favorably while rival efforts fare less well. Therefore, rather than do an injustice to much important work in an at- tempt to cover the whole field, I offer some definitely biased impressions and observations from my own experience in the 1950s. L 2. Programmers versus "Automatic Calculators" Programming in the early 1950s was really fun. Much of its pleasure re- sulted from the absurd difficulties that "automatic calculators" created for their would-be users and the challenge this presented. The programmer had to be a resourceful inventor to adapt his problem to the idiosyncrasies of the computer: He had to fit his program and data into a tiny store, and overcome bizarre difficulties in getting information in and out of it, all while using a limited and often peculiar set of instructions. He had to employ every trick 126 JOHN BACKUS he could think of to make a program run at a speed that would justify the large cost of running it. And he had to do all of this by his own ingenuity, for the only information he had was a problem and a machine manual.