Boston Youth Transportation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DCAMM Public Comment (PDF)

April 21, 2021 Loryn Sheffner Office of Real Estate Management Service Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance, 1 Ashburton Place, 15th Floor Boston, MA 02108 Dear Ms. Sheffner, A broad coalition of community members, organizations, neighbors and other organizations in partnership with Emerald Necklace Conservancy believe the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the City of Boston has an opportunity to supply the much-needed housing and health and supportive services in a superior location while also restoring 13-acres of parkland to high-needs, Environmental Justice Communities surrounding Franklin Park. Franklin Park is the Wrong Location for these Important Needs Franklin Park, a 527- acre gem of the Emerald Necklace, was designed in 1895 by Frederick Law Olmsted, and has since become a key open space for neighboring communities, providing a gathering space for events, as well as a welcome respite from city life. However, much of Forest Hills parkland is no longer Cemetary truly free and open to the public, with over Mattapan 200 acres altered, Figure 1: Map of Franklin Park, outlining areas not freely accessible including, the to the public (add neighborhood labels- community names) addition of the Preferred Location of 18-Acre Commonwealth-controlled Franklin Park Zoo, the “Arborway Yard” site William J. Devine Golf Course, and the Shattuck Hospital (built on what was formally Heathfield), and other facilities. As can be seen in the included figure 1, these uses are primarily sited on the Dorchester/Mattapan/Roxbury sides of the park, and limit accessible free and open space for those communities. These uses make up over 40% of Franklin Park, restricting open space availability and access in high-needs Environmental Justice Communities. -

Retail/Restaurant Opportunity Dudley Square

RETAIL/RESTAURANT OPPORTUNITY 2262 WASHINGTON STREET DUDLEY ROXBURY, MASSACHUSETTS SQUARE CRITICALDates NEIGHBORHOODOverview MONDAY • DECEMBER 9, 2013 Distribution of Request for Proposals (RFP) • Located at the junction of Washington and Warren Streets with convenient access to Interstates 93 and 90 (Massachusetts Bid Counter • 26 Court Street, 10th floor Turnpike) Boston, MA • Dudley Square has a population of approximately 80,000 people and 28,000 households within a one mile radius • Retail demand and spending by neighborhood residents is upwards of $610 million annually TUESDAY • JANUARY 14, 2014 • Approximately $300 million in public/private dollars have been invested in the neighborhood since 2000 Proposer Conference • 2:00 P.M. Central Boston Elder Services Buliding • Dudley Square is within a mile of Boston’s Financial District, blocks away from the South End and is within walking distance to 2315 Washington Street Northeastern University, Roxbury Community College, Boston Medical Center and BU Medical School and in proximity to Mission Hill and WARREN STREET Roxbury, MA Jamaica Plain • Dudley Square Station is located adjacent to the site and provides local bus service that connects Dudley to the MBTA’s Ruggles Station MONDAY • FEBRUARY 10, 2014 Orange Line stop and Silver Line service to Downtown Boston. Dudley Square Station is the region’s busiest bus station and Completed RFP’s due by 2:00 P.M. averages 30,000 passengers daily SEAPORT BOULEVARD BACK BAY SUMMER STREET Bid Counter • 26 Court Street, 10th floor COMMONWEALTH -

A Resource Guide to Programs and Services for Older Adults and Adults with Disabilities

The Green BookA resource guide to programs and services for older adults and adults with disabilities More benefits. $0 cost. If you are 65 or older and qualify for MassHealth Standard, our plan could get you more benefits than Original Medicare. With UnitedHealthcare® Senior Care Options (HMO SNP), your doctor, hospital and prescription drug coverage are all under one convenient card. Plus, you’ll get extra benefits — at no cost to you. These extra benefits include: $0 copay for dental $0 copay for all $0 copay $0 copay for cleanings, fillings, covered medications. for eyewear. rides to doctor dentures and more. appointments. Call 1-781-472-8650, TTY: 711, and one of our local, licensed agents can help you find out if you could get more benefits at no cost to you. UnitedHealthcare SCO is a Coordinated Care plan with a Medicare contract and a contract with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Medicaid program. Enrollment in the plan depends on the plan’s contract renewal with Medicare. This plan is a voluntary program that is available to anyone 65 and older who qualifies for MassHealth Standard and Original Medicare. If you have MassHealth Standard, but you do not qualify for Original Medicare, you may still be eligible to enroll in our MassHealth Senior Care Option plan and receive all of your MassHealth benefits through our SCO program. The benefit information provided is a brief summary, not a complete description of benefits. For more information contact the plan. Limitations, copayments and restrictions may apply. Benefits, formulary, pharmacy network, provider network, premium and/or copays/co-insurance may change on January 1 of each year. -

Community District Advisory Council Appointments

/tJ-?7 DISTRICT I NAME ADDRESS ~~:_~ College Prof. Joseph Ferreira-W Boston University 353-3231 School of Education 765 Commonwealth Ave. Boston, MA 02115 Business CEC Marlene Rubitski-W Just Around the Corner Theatre Co. 343 Huntington Ave. Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 BTU Joseph Broderick-W 126 Brayton Road Brighton, MA 02135 Rel. Rev. Eleanor Ivory-B One Gore Street 427-5561 Boston, MA 02120 ·I;' Com. Richard Driscoll~W YAC 3ll · wa~hington St. 254-4021 Brighton, MA o2135 Herman Santana-Hisp. BPEP 523-1890 73 Tremont Street, Rm.606 Boston, MA 02108 Alice Taylor-B Mission Hill Task Force 427-8709 P.O. Box 144 Roxbury, :f'.1A 02120 DISTRICT II NAME ADDRESS -~-r.,College Georgia Noble - W Simmons College 547-3723 Dept. of Education 300 the Fenway Bos·ton, MA Business \ . ~ · .. CEC ~: BTU Bob Banks - B 75 Morton Village Drive 298-0312 Mattapan, MA 02126 Rel. Rev. Pedro Rodriquez - Hisp. 437 South Htintington Ave. 524-4772 Jamaica Plain 02130 ~-- Comm. Jerrolyn Simpson - B Eight Marbury Terrace 522-9484 Jamaica Plain 02130 Enos ~1atozzi - w 15 Montebello Road 524-0620 Jamaica Plain 02130 Bonnie Gorman - W P.O. Box 4 522-5060 Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 DISTRICT III NAME ADDRESS College George Ladd - W Boston College Chestnut Hill , MA 02167 -~·It . Bus. Vincent Santosuosso - W New Eng . Merchants Bank 742-4000 One Washington Mall Boston , MA 0 2110 CEC Susan Gassett - W City Stage 539 Tremont Street Boston, MA 0 2116 BTU Brenda Black - B 130 Orlando Street Mattapan, MA 0 2126 Rel. Father ThoBas Usher -B 669 Walk Hill Street Mattapan , MA Comm . -

Boston Redevelopment Authority Thomas M

Supermarket Openings INTRODUCTION l Beginning around 1950, Boston, 1993 l In 1993, two more new supermarkets opened in The largest supermarket to come on line during this like other American cities, saw a change in the retail Boston – each very different, but each a kind of trail- period was a nearly 40,000 square feet “Super” 88 food industry. Large supermarkets (defined within the blazer in its market. The first was a giant (almost market that opened right next door to the “Super” Stop New industry as stores occupying more than 10,000 square 70,000 square feet) “Super” Stop & Shop that in addi- & Shop in the South Bay Mall – dramatic proof of the Good News for feet of selling space or with annual sales of more than tion to becoming Boston's largest supermarket served strength of both the urban and ethnic market in Boston. Boston’s Neighborhoods $2 million) gradually replaced the smaller “corner store” as the “anchor store” for the South Bay Mall, an ambi- as the place where residents bought most of their food. tious – and successful – development at the intersec- 2002 – 2004 The purchasing power of the residents In 1992, the closing of four neighborhood supermar- l By 1990, according to one retail authority, 20 to 30 tion of Dorchester, South Boston and Roxbury. This of Boston’s neighborhoods and the strength of kets prompted concern on the part of Boston residents large supermarkets in Boston had replaced between store demonstrated just how strong Boston’s inner-city Boston’s economy continued to generate additional and city officials. -

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study

Roxbury-Dorchester-Mattapan Transit Needs Study SEPTEMBER 2012 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the State Planning and Research Program, Section 505 [or Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f)] of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. This report was funded in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration [and Federal Transit Administration], U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the authors [or agency] expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation. i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 A Lack of Trust .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 The Loss of Rapid Transit Service ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

Retail Pharmacies, Including Chain Pharmacies

Retail Pharmacies, East Falmouth Harwich Port including Chain Pharmacies CVS PHARMACY #01870 * OSCO PHARMACY #4596 * 419 E Falmouth Hwy 18 Sisson Rd MASSACHUSETTS East Falmouth, MA 02536 Harwich Port, MA 02646 Barnstable (508) 540-8621 (508) 432-0895 Bourne COMMUNITY HEALTH OSCO PHARMACY #0603 * OUTER CAPE HEALTH CENTER OF CAPE COD 137 Tea Ticket Hwy SERVICES PHARMACY BOURNE * East Falmouth, MA 02536 HARWICH PORT * 123 Waterhouse Road (508) 457-1185 710 Route 28 Bourne, MA 02532 Harwich Port, MA 02646 (508) 539-6090 WALMART PHARMACY (774) 237-9000 10-3561 * CVS PHARMACY #01576 * 137 Teaticket Highway Harwichport 6 Head Of Bay Rd East Falmouth, MA 02536 CVS PHARMACY #00860 * Bourne, MA 02532 (508) 540-9196 Main St 6 Post Office Square (508) 759-1097 Harwichport, MA 02646 Falmouth (508) 430-0660 STOP & SHOP PHARMACY * CAPE COD HEALTHCARE 1 Trowbridge Place PHARMACY AT FALMOUTH Hyannis Bourne, MA 02532 HOSPITAL * CAPE COD HEALTHCARE (508) 743-9563 100 Ter Heun Drive PHARMACY AT CAPE COD Falmouth, MA 02540 HOSPITAL * Chatham (508) 495-7520 27 Park St CVS PHARMACY #01878 * Hyannis, MA 02601 12 Queen Anne Rd CVS PHARMACY #00594 * (508) 862-5900 Chatham, MA 02633 105 Davis Straits (508) 945-4340 Falmouth, MA 02540 CVS PHARMACY #01869 * (508) 540-4307 1080 Falmouth Rd Dennis Port Hyannis, MA 02601 WALGREENS #19983 * STOP & SHOP PHARMACY * (508) 778-4064 711 Main Street 20 Teaticket Highway Dennis Port, MA 02639 Falmouth, MA 02536 CVS PHARMACY #02322 * (508) 398-5097 (508) 540-4711 176 North St Hyannis, MA 02601 E Harwich WALGREENS #19592 * (508) 775-8346 CVS PHARMACY #01859 * 520 Main Street 148 Route 137 Falmouth, MA 02540 CVS PHARMACY #10852 * E Harwich, MA 02645 (508) 495-2931 411 Barnstable Rd (508) 432-2018 Hyannis, MA 02601 Harwich (508) 771-4753 STOP & SHOP PHARMACY * 111 Chatham Rd Harwich, MA 02645 (508) 432-5001 * This pharmacy qualifies for dispensing up to a 90-day supply. -

Arborway Road Safety Audit

ROAD SAFETY AUDIT Arborway - West of South Street to West of Eliot Street City of Boston September 9, 2019 Prepared For: DCR Prepared By: Howard Stein Hudson 11 Beacon Street, Boston, MA Road Safety Audit—Arborway – West of South Street to Eliot Street, Boston Prepared by Howard Stein Hudson FINAL Table of Contents Contents Background ................................................................................................................................. 1 Project Location and Description .............................................................................................. 3 Project Crash Data ................................................................................................................... 10 Audit Observations and Potential Safety Enhancements...................................................... 11 Overall Arborway Corridor ............................................................................................................... 11 Safety Issue #1: Speed ....................................................................................................................... 11 Potential Enhancements: ............................................................................................................. 11 Safety Issue #2: Pedestrian, Bicycle, and ADA Accommodations ................................................... 12 Potential Enhancements: ............................................................................................................. 12 Safety Issue #3: Lighting .................................................................................................................. -

The Power of Community

MATTAPAN THE POWER OF COMMUNITY By Borja Santos Porras Mattapan Neponset river Greenway Mattapan is a predominantly residential neighborhood in the south of The Neponset River Greenway on the Boston and Milton shore of the Boston. The Native American Mattahunt Tribe inhabited Mattapan in the River is a miles-long, multi-use trail that connects a series of parks and early 1600s, and the name they gave it seems to mean “a good place to provides an exciting opportunity to appreciate the outdoors in an sit”. Although some statistics and past stories have stigmatized its otherwise urban area. It was opened in 2001, however, one “missing reputation, many neighbors and associations fight on daily basis to build link” has been uncompleted for more than a decade. It was only in 2015 a better district, encouraging everyone to come and visit any time. The scale model of the that the work started for the 1.3-mile section between Central Avenue in greenway shows how Milton and Mattapan Square, which included a pedestrian bridge where Mattapan has a population of 36,480 with a very ethnically and culturally the construction is the trail would cross the river from Milton to Mattapan. diverse black/African American community (74%). Out of the foreign bordering the river in population 48% of the foreign-born population are from Haiti, 24% from its pass through For many citizens of Mattapan, this project symbolizes the abandonment Jamaica, 14% from the Dominican Republic, 8% from Vietnam and 6% Mattapan without that Mattapan experiences. “It is difficult to explain why this stretch from Trinidad and Tobago. -

Folkman Auditorium, Enders Building, 320 Longwood Avenue, Children’S Hospital Boston

Baseball Pitching Health and Performance Seminar December 5, 2010 – Folkman Auditorium, Enders Building, 320 Longwood Avenue, Children’s Hospital Boston Directions From the north: Via Routes 1, 93, and 28 Follow the signs for Storrow Drive. After the Copley Square/Massachusetts Avenue sign, take the left exit off Storrow Drive marked Fenway, Route 1. Take the right fork marked Boylston Street, Outbound. At the major intersection, go straight onto Brookline Avenue, past Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center-East Campus to Longwood Avenue intersection. At this major intersection, turn left onto Longwood Avenue. Children's main entrance is two blocks down on the right. Children's Parking Garage is on the left Once at the Children’s garage, cross the street towards the main building. After crossing the street, turn right under the overhead bridge and Enders will be directly in front. Proceed to the Folkman Auditorium From the south: Via Routes 1, 28 and 138 From Route 1, continue to the Jamaicaway. From Routes 28 or 138, proceed via Morton Street and the Arborway to the Jamaicaway. Continue on the Jamaicaway as it turns into the Riverway. At the Brookline Avenue traffic light, turn right onto Brookline Avenue. Continue to the third traffic light and turn right onto Longwood Avenue. Children's main entrance is two blocks down on the right. Children's Parking Garage is on the left. Once at the Children’s garage, cross the street towards the main building. After crossing the street, turn right under the overhead bridge and Enders will be directly in front. Proceed to the Folkman Auditorium From the west: Via the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90) Take Exit 22 at Copley Square/Prudential. -

Introduction

DRAFT MEMORANDUM DATE November xx, 2012 TO Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization FROM Mark Abbott and Bill Kuttner MPO Staff RE Safe Access to Transit for Pedestrians and Bicycles: Morton Street Commuter Rail Station Introduction The Morton Street commuter rail station, located at 865 Morton Street, in Mattapan, was selected to be included in the Safe Access to Transit for Pedestrians and Bicyclists Study. This study examines nonmotorized accessibility issues related to Morton Street Station and identifies short- and long-term measures that may improve pedestrian and bicyclist access to the Metropolitan Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) system. Morton Street Station was selected based on the following factors: • Identified as needing improvements according to a qualitative MBTA station access assessment.1 • Located in an area with a high density of employment, retail activity, and/or population. • Located in an area with a high crash rate for vehicles, pedestrians, and/or bicyclists. • Of the large number of passengers boarding or alighting at Morton Street Station (almost 203 on an average weekday), about 61.7% walk, 0% bike, and 0% use an MBTA bus to access the station or to travel from the station to their destinations.2 This station has one of the lowest percentages of bike access among stations with a high population or employment density. • There is no parking for motor vehicles, and there are only 20 bike parking spaces at this station; the surrounding area lacks pedestrian amenities. 1 Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization, “Needs Assessment (Volume 2 of Paths to a Sustainable Region), produced by the Central Transportation Planning Staff, September 27, 2011. -

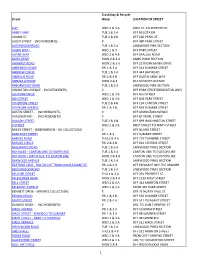

Trash & Recycle Schedule

Trash Day & Recycle Street Week LOCATION OF STREET A ST. WED.1 & 3 A FIRST ST. TO SEVENTH ST. ABBEY LANE TUE.1 & 3 A OFF DECOTA DR. ADAMS ST. TUE.2 & 4 B OFF 166 PEARL ST. ALDER STREET ‐ (NO RESIDENTS) X OFF 480 PARK STREET ALDERWOOD ROAD TUE.1 & 3 A LAKEWOOD PINE SECTION ALGER WAY ‐ WED.1 & 3 OFF PARK STREET ALPINE WAY WED.2 & 4 B OFF SPALLUS ROAD AMES DRIVE MON.2 & 4 A AMES POND SECTION AMHERST ROAD MON.1 & 3 A OFF 22 RALPH MANN DRIVE ANDERSON ROAD FRI.1 & 3 A OFF 614 SUMNER STREET ANDREW CIRCLE TUE.1 & 3 A OFF 444 BAY ROAD ANGELOS ROAD FRI.2 & 4 B OFF QUEEN ANNE WAY ANNINA AVENUE MON.2 & 4 OFF 60 SMITH AVENUE ARBORWOOD ROAD TUE.1 & 3 A LAKEWOOD PINE SECTION ARLINGTON AVENUE ‐ (NO RESIDENTS) X OFF PARK STREET(BROCKTON LINE) ASH PARK DRIVE WED.1 & 3 B OFF ASH STREET ASH STREET WED.1 & 3 B OFF 803 PARK STREET ATHERTON STREET TUE.2 & 4 B OFF 134 CANTON STREET ATKINSON AVENUE FRI.1 & 3 B OFF 693 SUMNER STREET AUSTIN STREET ‐ (NO RESIDENTS) X OFF ARLINGTON AVENUE AVALON PARK ‐ (NO RESIDENTS) X OFF 87 PEARL STREET AVALON STREET TUE.2 & 4 B OFF 699 WASHINGTON STREET B STREET WED.1 & 3 B FIRST STREET TO NINTH STREET BAILEY STREET ‐ (GREENBROOK ‐ NO COLLECTION) X OFF ISLAND STREET BANCROFT STREET FRI.1 & 3 OFF SUMNER STREET BARNES ROAD THU.2 & 4 A OFF 779 TURNPIKE STREET BASSICK CIRCLE FRI.2 & 4 B OFF 601 CENTRAL STREET BASSWOOD ROAD TUE.1 & 3 A LAKEWOOD PINES SECTION BAY ROAD ‐ CANTON LINE TO SMITH AVE.