Supplemental Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lehigh University Choral Arts Lehigh University Music Department

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Performance Programs Music Spring 5-3-2002 Lehigh University Choral Arts Lehigh University Music Department Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lehigh University Music Department, "Lehigh University Choral Arts" (2002). Performance Programs. 155. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs/155 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BAKER HALL• ZOELLNERARTS CENTER . I I Lehigh Univer. ity Music Department 2001 - 2002 SEASON Welcome to Zoellner Arts Center! We hope you will take advantage of all the facilities, including Baker Hall, the Diamond and Black Box Theaters, as well as the Art Galleries and the Museum Shop. There are restrooms on every floor and concession stands in the two lobbies. For all ticket information, call (610) 7LU-ARTS (610-758-2787). To ensure the best experience for everyone, please: Bring no food or drink into any of the theaters Refrain from talking while music is being performed Refrain from applause between movements Do not use flash photography or recording devices Turn off all pagers and cellular phones Turn off alarms on wrist watches Do not smoke anywhere in the facilities MUSIC DEPARTMENT STAFF Professors - Paul Salemi, Steven Sametz, Nadine Sine (chair) -

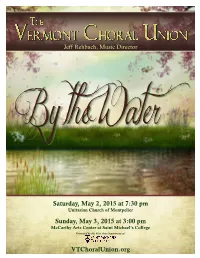

Spring 2015 Concert Program

Jeff Rehbach, Music Director KEMessier © 2015 Saturday, May 2, 2015 at 7:30 pm Unitarian Church of Montpelier Sunday, May 3, 2015 at 3:00 pm McCarthy Arts Center at Saint Michael’s College Presented by the Fine Arts Department at: VTChoralUnion.org The Vermont Choral Union, Spring 2015 Soprano Alto Celia K. Asbell* Burlington Clara Cavitt Jericho Mary Dietrich Essex Junction Michele Grimm Huntington Megumi Esselstrom Essex Junction Mary Ellen Jolley* St. Albans Lena Goglia Burlington Terry Lawrence Burlington Ann Larson Essex Lisa Raatikainen Burlington Kathleen Messier* Essex Junction Charlotte Reed Underhill Kayla Tornello Essex Junction Judy Rosenbaum Winooski Lindsay Westley Hinesburg Lynn Ryan Colchester Martha Whitfield Charlotte Maureen Sandon Essex Junction Sarah Woodward Burlington Karen Speidel Charlotte Tenor Bass Mark Kuprych Burlington James Barickman Underhill Rob Liotard Starksboro Douglass Bell* St. Albans Jack McCormack Burlington Jonathan Bond South Burlington Peter Sandon Essex Junction Joe Comeau Alburgh Paul Schmidt Burlington Robert Drawbaugh* Essex Junction Maarten van Ryckevorsel Winooski Peter Haskell* Burlington John Houston * Board members Larry Keyes* Colchester Richard Reed Morrisville About the Vermont Choral Union Originally called the University of Vermont Choral Union, the ensemble was founded in 1967 by James G. Chapman, Professor of Music at the University of Vermont. Dr. Chapman directed the choir until his retirement in 2004. At that time, the group's name changed to the Vermont Choral Union, and Gary Moreau, well-known Vermont music educator and singer, succeeded Dr. Chapman as director through 2010. Carol Reichard, director of the Colchester Community Chorus, served as the Choral Union's guest conductor in Spring 2011. -

Musical Influence and Style in the Choral Music of Steven Sametz by Douglas R

MAY 2002 CHORAL JOURNAL Musical Influence and Style in the Choral Music of Steven Sametz by Douglas R. Boyer Interactive Article - www.acdaonline.org/cj/interactive/may2002 Editors note: Many of the musical figures for this article and Princeton Singers, and has been guest conductor for such groups additional sound clips can be viewed and heard on our Web site as the Netherlands National Radio Choir, Taipei Philharmonic, <www.acdaonline.org/cj/interactive/may2002/>. Santa Fe Desert Chorale, Berkshire Festival, and the New York Chamber Symphony. 2 Perhaps best known for his composition I Have Had Sing Sametzs substantial output includes fifty choral works, fif ing, made famous by the male vocal ensemble Chanticleer, teen solo vocal works, a choral symphony, a chamber opera' and Steven Sametz is becoming recognized as a composer of con numerous orchestral and instrumental works. This article ex siderable depth and creativity. His compositions have been plores his musical influences and compositional style as seen in heard throughout the world: the Tanglewood, Ravinia, his choral music. Salzburg, Schleswig-Holstein, and Santa Fe music festivals. Such ensembles as Chanticleer, the Dale Warland Singers, the Musical Influences Sametz (b.1954) grew up in Westport, Connecticut, in a Santa' Fe Desert Chorale, the Philadelphia Singers, the Pro home filled with piano music. His father and older brother Arte Chamber Choir, and the Princeton Singers, among oth played the piano. The six-year-old Steven began imitating his ers, have commissioned his works. His first symphony, older brother at the keyboard. He recalls this memory: Carmina amaris, premiered the spring of 2001 to rave re views! and immediately captured the attention of one of his I started playing and writing on my own early in life. -

Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-10-2012 Concert: The Thirty-Fourth Annual Ithaca College Choral Composition Contest Ithaca College Choir Lawrence Doebler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ithaca College Choir and Doebler, Lawrence, "Concert: The Thirty-Fourth Annual Ithaca College Choral Composition Contest" (2012). All Concert & Recital Programs. 4058. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/4058 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. THE THIRTY-FOURTH ANNUAL ITHACA COLLEGE CHORAL COMPOSITION CONTEST Sponsored jointly by Ithaca College and Roger Dean Publishing Company Ford Hall Saturday November 10th, 2012 7:00 pm ITHACA COLLEGE THIRTY-FOURTH ANNUAL CHORAL COMPOSITION CONTEST AND FESTIVAL Sponsored jointly by Ithaca College and Roger Dean Publishing Company Professor Lawrence Doebler founded the Choral Composition Festival in 1979 to encourage the creation and performance of new choral music and to establish the Ithaca College Choral Series. Six scores were chosen for performance this evening from entries submitted from around the world. The piece …to balance myself upon a broken world (September, 1918) (Amy Lowell) by Paul Carey was commissioned by Ithaca College and -

Evolution Lehigh University Music Department

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Performance Programs Music Fall 9-26-2009 (r)evolution Lehigh University Music Department Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Lehigh University Music Department, "(r)evolution" (2009). Performance Programs. 2. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-music-programs/2 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lehigh University Music Department presents (r )e'V""o1u..~ion.. The Princeton Singers Steven Sametz, director I . I - 1.1-, .. i •. - - ...; ! .. ,,... Saturday, September 26, 2009 8 pm Baker Hall Zoellner Arts Center Welcome to Zoellner Arts Center! We hope you will take advantage of all the facilities, including Baker Hall, the Diamond and Black Box Theaters, as well as the Art Galleries and the Museum Shop. There are restrooms on every floor and concession stands in the two lobbies. For ticket information, call (610) 7LU-ARTS (610- 758-2787) or visit www.zoellnerartscenter.org. To ensure the best experiencefor everyone, please: • Bring no food or drink into any of the theaters • Refrain from talking while music is being performed • Refrain from applause between movements • Do not use flash photography or recording devices • Turn off all pagers and cellular phones • Turn off alarms on wrist -

Lehigh University Music Department 2014-2015 Season

Lehigh University Music Department 2014-2015 Season Baker Hall Zoellner Arts Center www. lehigh. edulmusic I] LU MusicDept t' 88.1 LEHIGH VALLEY ••1•11• COMMUNITY PUBLIC RADIO 93.7 FM WEST 93.9 FM EAST j Lehigh University Music D;;:::r~ ~ Lehigh Choral Arts I Dream a World ~ Steven Sarnetz, Artistic Directo~ Sun Min Lee, Associate Director with Anthony Leach, Guest Conductor April 24 & 25, 2015 8pm Baker Hall Zoellner Arts Center Welcome to Zoellner Arts Center! We hope you will take advantage of all the facilities, including Baker Hall, the Diamond and Black Box Theaters, as well as the Art Galleries and the Museum Shop. There are restrooms on every floor and concession stands in the two lobbies. For ticket information, call (610) 758-2787 or visit www.zoellnerartscenter.org. To ensure the best experiencefor everyone, please: • Bring no food or drink into any of the theaters • Refrain from talking while music is being performed • Refrain from applause between movements • Do not use flash photography or recording devices «Turn off all pagers and cellular phones • Turn off alarms on wrist watches • Do not smoke anywhere in the facilities MUSIC DEPARTMENT STAFF Professors - Paul Salemi, Steven Sametz, Nadine Sine (chair) Associate Professors - Eugene Albulescu, William Warfield Professors of Practice - Michael Jorgensen, Sun Min Lee Lecturer - David Diggs Adjuncts/ Private Instructors - Deborah Andrus, Helen Beedle, Daniel Braden, Colin Brigstocke , Amanda Cortezzo , Bob DeV os, Megan Durham, Susan Frickert, Linda Ganus, Christopher Gross, -

Archive: Enewsletter December 2011 UC Berkeley Department of Music A

Archive: eNewsletter December 2011 UC Berkeley Department of Music A Letter from the Chair ................................................................................................................................. 3 Featured Stories ............................................................................................................................................ 4 A Music Student recently had the opportunity to accompany Chancellor Birgeneau to Shanghai ......... 4 Visiting Postdocs bring unique research interests and popular classes to the Music Department. ........ 4 Graduating student starts a musical theatre tradition ............................................................................. 4 The Music Department offers a wide array of performances on Cal Day ................................................ 4 Collections of the Hargrove Music Library were on display at the invitation of the Antiquarian Bookseller's Association of America ......................................................................................................... 5 Precious instruments donated to the department provide Berkeley students the chance of a lifetime . 5 Student wins second place in national performance competition on a donated instrument—the 19th‐ century Ted Rex cello ................................................................................................................................ 6 Emeritus professors honored for their distinguished contributions to scholarship, and for their cherished activities over the -

A Chanticleer Christmas Thursday December

A CHANTICLEER CHRISTMAS THURSDAY DECEMBER : PM MEMORIAL CHURCH R E L H O K A S I L Y B O T O H P Program Notes by Kip Cranna, Andrew Morgan, Joseph Jennings, Kory Reid, Gregory Peebles, and Jace Wittig Virga Jesse floruit Plainsong Gregorian Chant, named after Pope Gregory I (d .604), is the term applied to the vast repertoire of liturgical plainsong assembled over the course of several hundred years, roughly 700-1300 A.D. There are almost 3,000 extant chants in the Gregorian repertoire, with texts specific to each day of the liturgical year in the Roman Catholic Church. Virga Jesse floruit is an Alleluia for the Feast of the Annunciation during Paschal Time (which in fact is a rare occasion). Alleluia. Alleluia. Virga Jesse floruit: The rod of Jesse has blossomed: Virgo Deum et hominem genuit: a Virgin hath brought forth God and man: pacem Deus reddidit, God hath restored peace, in se reconcilians ima summis, reconciling in Himself the lowest with the highest, Alleluia. Alleluia. o Virgo virginum Josquin Desprez ( c. 1450–1521) Considered one of the greatest composers of the Renaissance, Josquin Desprez lived a life steeped in mystery for present-day scholars. The earliest surviving written record dates from 1459, which lists him as an “adult” singer at the cathedral in Milan, where he was employed until 1472. He subsequently worked at the chapel of Duke Galeazzo Sforza. Other posts included serving as a singer in the Papal Chapel in Rome and as court composer to Duke Ercole I of Ferrara. -

Harmonium Chamber Singers Spring 2014 Body Parts: Sacred and Profane Dr

Harmonium Chamber Singers Spring 2014 Body Parts: Sacred and Profane Dr. Anne Matlack, Artistic Director Never Weather-Beaten Sail Thomas Campion (1567 –1620) Osculetur me Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525-1594) Willow Song Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) Desiderium animae (women) George Malcolm (1917-1997) Oculi omnium (men) Andrew Parnell (b.1954) (Half of the group each): A Silly Sylvan, Kissing Heav’n Born Fire John Wilbye (1574-1638) Take, O Take Those Lips Away Robert Pearsall (1795-1856) Take, O Take Those Lips Away Matthew Harris (b. 1956) Shakespeare Songs, Book II Small groups: O occhi manza mia Orlando di Lasso (1532-1594) Your Shining Eyes Michael East (ca. 1580–1648) Weep O Mine Eyes John Bennet (c. 1575 – after 1614) Si ch’io vorrei morire Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) INTERMISSION Since First I Saw Your Face Thomas Ford (1580-1648) Small groups: Four arms, Two Necks, One Wreathing Thomas Weelkes (1576-1623) April Is In My Mistress’ Face Thomas Morley (1558 -1603) Jamais je n’aymerais grant home Anon., published by Pierre Attaignant Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye Irish folksong, arr. Alice Parker (b. 1925) Let Thy Merciful Ears O, Lord Thomas Mudd (1619-1667) Queen Jane (women) Alice Allen Kentucky Folksong, arr. S. Hatfield (b. 1956) God Be In My Head H. Walford Davies (1869-1941) Alouette French folksong arr. Robert Sund (b.1942) Lamma Badaa Yatathannaa Marilyn Kitchell Trad. Muwashshah, arr. Shireen Abu-Khader Pai duli Russian folksong arr. Steve Sametz (b.1954) Thomas Campion was such the Renaissance man that he attended medical school and was a practicing physician, yet was well-known in his time for his poems and treatises on poetry. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer

Tanglewqpd SEIJI OZAWA HALL Wednesday, July 10, at 8:30 Florence Gould Auditorium, Seiji Ozawa Hall CHANTICLEER Texts and Translations I. GUILLAUME DUFAY (c. 1400-1 474) Gloria ad modum tubae Gloria ad modum tubae Trumpet Gloria Gloria in excelsis Deo. Glory to God in the highest. Et in terra pax hominibus bonae And on earth, peace to men of good will. voluntatis. Laudamus te, benedicimus te, We praise You, we bless You, adoramus te, glorificamus te. we worship You, we glorify You. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam We give You thanks for Your great glory. gloriam tuam. Domine Deus, Rex caelestis, Lord God, Heavenly King, Deus Pater omnipotens. God the Father Almighty. Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe. Lord the only begotten Son, Jesus Christ. Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris. Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father. Qui tollis peccata mundi, You who take away the sins of the world, miserere nobis. have mercy on us. Qui tollis peccata mundi, You who take away the sins of the world, suscipe deprecationem nostram. receive our prayer. Qui sedes ad dexteram patris, You who sit at the right hand of the Father, miserere nobis. have mercy on us. Quoniam tu solus sanctus, tu solus For You alone are holy, You alone are the Dominus, Lord, tu solus altissimus, Jesu Christe. You alone are most high, Jesus Christ. Cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris. With the Holy Spirit in the glory of God the Father. Amen. Amen. Please turn the page quietly. Design Team for Seiji Ozawa Hall: William Rawn Associates, Architect Lawrence Kirkegaard & Associates, Acousticians Theatre Projects Consultants, Inc., Theatrical Consultant Week 2 mm II. -

諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 Br皿ant Years of Singing Pure Gospel with the Soul Stirrers, The

OCk and ro11 has always been a hybrid music, and before 1950, the most important hybrids pop were interracial. Black music was in- 恥m `しfluenced by white sounds (the Ink Spots, Ravens and Orioles with their sentimental ballads) and white music was intertwined with black (Bob Wills, Hank Williams and two generations of the honky-tOnk blues). ,Rky血皿and gQ?pel, the first great hy垣i立垂a血QnPf †he囲fti鎧T臆ha陣erled within black Though this hybrid produced a dutch of hits in the R&B market in the early Fifties, Only the most adventurous white fans felt its impact at the time; the rest had to wait for the comlng Of soul music in the Sixties to feel the rush of rock and ro11 sung gospel-Style. くくRhythm and gospel’’was never so called in its day: the word "gospel,, was not something one talked about in the context of such salacious songs as ’くHoney Love’’or ”Work with Me Annie.’’Yet these records, and others by groups like theeBQ聖二_ inoes-and the Drif曲 閣閣閣議竪醒語間監護圏監 Brown, Otis Redding and Wilson Pickett. Clyde McPhatter, One Of the sweetest voices of the Fifties. Originally a member of Billy Ward’s The combination of gospel singing with the risqu6 1yrics Dominoes, he became the lead singer of the original Drifters, and then went on to pop success as a soIoist (‘くA I.over’s Question,’’ (、I.over Please”). 諾箋護憲薫葦嵩叢 br皿ant years of singing pure gospel with the Soul Stirrers, the resulting schism among Cooke’s fans was deeper and longer lasting than the divisions among Bob Dylan’s partisans after he went electric in 1965. -

The Gospel Side of Specialty Records – the Post-War Period

The Gospel Side of Specialty Records – The Post-War Period by Opal Louis Nations A historical backdrop: It is generally acknowledged that almost from the start of Art Rupe’s involvement in the country’s popular vernacular musics, gospel and spiritual expressions were among his keenest passions. He would often drop in on a church gospel program and sometimes shed a tear when moved by a particular jubilee quartet spinning on a phonograph. Rupe told me that during his boyhood he was exposed to gospel music emanating from the open windows in the summer from the African American Baptist church in his hometown neighborhood in Pennsylvania. Rupe did not fit the stereotypical hard-nosed, cash-driven, stogie-stompin’ record mogul. He was an intelligent, quiet, analytical and compassionate character who not only got involved in disseminating black talent to make a quick buck but genuinely enjoyed the musics he put out. At the close of gospel’s golden age, when the 1960s came around, the popular music industry began to transform itself into one that conjoined politics with culture. 1964 saw the advent of “The British Invasion.” A year later rock & roll had fully matured into rock and its separate audiences had blended into one and, says Philip H. Ennis in his 1992 book, The Seventh Stream (the seven different types of popular __________________________________________________________ The Gospel Side of Specialty Records, p./1 © 2011 Opal Louis Nations music, published by Wesleyan University Press), the musical materials and performers from the separate streams were combined to form a new and different idiom with its own artists and music.