CHAPTER-VIII · Origin of Identity Crisis: Response and Reaction Among the Rajbanshis in All Indian Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutritional and Medicinal Value of Some Underutilized Vegetable Crops of North East India- a Review

Buragohain and Brahma Available Ind. J. Pure online App. at Biosci. www.ijpab.com (2020) 8(5), 493 -502 ISSN: 2582 – 2845 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18782/2582-2845.8383 ISSN: 2582 – 2845 Ind. J. Pure App. Biosci. (2020) 8(5), 493-502 Review Article Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Open Access Journal Nutritional and Medicinal Value of Some Underutilized Vegetable Crops of North East India- A Review Nayanmoni Buragohain1* and Sanchita Brahma2 1Assistant Professor, Biswanath College of Agriculture, AAU, Biswanath Chariali, Assam 2Assistant Professor, Sarat Chandra Singha College of Agriculture, AAU, Dhubri, Assam *Corresponding Author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 9.09.2020 | Revised: 17.10.2020 | Accepted: 26.10.2020 ABSTRACT To provide safe, healthy and nutritious source of food for poor income group and undernourished population is still a big challenge for our country. On the other hand, there is an increasing demand of antioxidant, calories and protein rich quality, healthy, nutritious food by the health conscious modern people. Underutilized vegetable crops are important source of valuable nutritional and medicinal component. These are cheaper and affordable than the exotic imports. Exploitation of these wild resources is an important way of income and food, especially for the poor farmers who are also underemployed. Keywords: Nutritional value, Medicinal value, Underutilized, Vegetables, North East India. INTRODUCTION the population is tribal. The primary factor for The Northeastern India is a chicken-necked their economy is agriculture, contributing up region connected to the mainland with a to 45% of the total economy of the region. narrow corridor and touching the international Northeast India has a subtropical boundaries of Myanmar, China, Bangladesh, climate that is influenced by its relief and Bhutan and Nepal. -

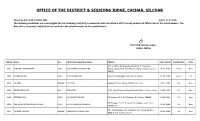

Office of the District & Sessions Judge, Cachar

OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT & SESSIONS JUDGE, CACHAR, SILCHAR Memo No.JCD.III/GR.IV/2020/ 4082 Dated:- 21-11-2020 The following candidates are found eligible for the Screening Test(Oral) in connection with recruitment of 07 (seven) numbers of Office Peon of this establishment. The date of the Screening Test(Oral) will be notified in the official website of this establishment. District & Sessions Judge, Cachar, Silchar Roll No. Name Sex Father Name/Guardian Name Address Date of Birth Qualification Caste C/O. Lt. Dhiraj Purkayastha, Ward No. 2, Malugram, 0001 DHRUBA PURKAYASTHA MALE LATE DHIRAJ PURKAYASTHA Shibbari Road, Near E & D Bandh, Silchar, Cachar, Assam - 06.06.1986 H.S.L.C Gen 788002 0002 DIPANKAR DAS MALE DILIP KUMAR DAS Vill & P.O- Masughat, Dist- Cachar, Assam 31.08.1988 H.S.L.C S.C 0003 JIKU DEB FEMALE DILIP DAS Mabadeb Tilla, Haflong, District- N.C. Hills 28.01.1987 H.S Gen 0004 SIDDHARTHA KAR MALE PIJUSH KAR 196 C, Alok Bhawan, Hospital Road, Silchar, Cachar, Assam 18.06.1990 H.S. Gen 0005 UTTAM NUNIA MALE RAGHUNATH NUNIA Vill- Kashipur Pt-I, P.O Kashipur, P.S- Silchar-788009 23.09.2000 H.S Gen Vill- Rongpur Pt-VI,P.S- Lala, P.O- Rongpur south, Dist- 0006 ARSHADUR RAHMAN MAZUMDER MALE FAKHAR UDDIN MAZUMDER 11.02.1999 H.S Gen Hailakandi Vill.- Gobindakupa, P.O. Digorkhal, P.S. Katigorah, PIN - 0007 MOUSMITA PAUL FEMALE RAMENDRA MOHAN PAUL 20.04.1994 H.S. Gen 788815, Dist. Cachar, Assam Roll No. Name Sex Father Name/Guardian Name Address Date of Birth Qualification Caste Vill- Rongpur Pt-VI,P.S- Lala, P.O- Rongpur south, Dist- 0008 SHAIDUR RAHMAN MAZUMDER MALE FAKHAR UDDIN MAZUMDER 06.10.2000 H.S Gen Hailakandi 0009 SHIBOM SANKAR MALAKAR MALE SHIBU MALAKAR Vill- Nayabari, P.O- Tillabazar, Dist- Karimganj, Pin-788709 19.08.1994 H.S S.C Vill.- Jarailtala, P.O. -

Factional Politics in Assam: a Study on the Asom Gana Parishad

Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Doctoral Thesis Factional Politics in Assam: A Study on the Asom Gana Parishad Dipak Kumar Sarma Registration No. 09614110 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the discipline of Political Science Supervisors: Prof. Abu Nasar Saied Ahmed & Prof. Archana Barua Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Guwahati-781039, Assam, India August, 2017 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati - 781039 Assam, India Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Factional Politics in Assam: A study on the Asom Gana Parishad” , is the outcome of my research duly carried out in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS), Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, under the joint supervision of Prof. Abu Nasar Saied Ahmed and Prof. Archana Barua. The academic investigations and reporting of the scientific observations are in conformity with the general norms and standard of research. This thesis or any part of it has not been submitted to any other University/Institute or elsewhere for the award of any other degree or diploma. IIT Guwahati (Dipak Kumar Sarma) Date: August, 2017 Research Scholar TH-1788_09614110 Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Guwahati - 781039 Assam, India Certificate This is to certify that Mr. Dipak Kumar Sarma has prepared the thesis entitled “Factional Politics in Assam: A study on the Asom Gana Parishad” for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences of Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati. -

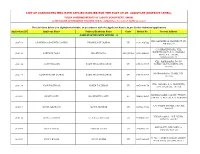

List of Candidates Who Have Applied Earlier for the Post of Jr. Assistant (District Level)

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE APPLIED EARLIER FOR THE POST OF JR. ASSISTANT (DISTRICT LEVEL), UNDER COMMISSIONERATE OF LABOUR DEPARTMENT, ASSAM, AS PER EARLIER ADVERTISEMENT PUBLISHED VIDE NO. JANASANYOG/ D/11915/17, DATED 20-12-2017 The List Given below is in Alphabetical Order, in accordance with the Applicant Name ( As per Earlier Submited Application) Application ID Applicant Name Fathers/Husbands Name Caste Mobile No. Present Address NAME STARTING WITH LETTER: - 'A' VILL DAKSHIN MOHANPUR PT VII, 200718 A B MEHBOOB AHMED LASKAR NIYAMUDDIN LASKAR UR 9101308522 PIN 788119 C/O BRAJEN BORA, VILL. KSHETRI GAON, P.O. CHAKALA 206441 AANUPAM BORA BRAJEN BORA OBC/MOBC 9401696850 GHAT, P.S. JAJORI, NAGAON782142 VILL- MAIRAMARA, PO+PS- 200136 AASIF HUSSAIN ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 HOWLY, DIST-BARPETA, PIN- 781316 MOIRAMARA PO-HOWLI, PIN- 200137 AASIF HUSSAIN LASKAR ZAKIR HUSSAIN LASKAR UR 8753915707 781316 VILL.-NAPARA, P.O.-HORUPETA, 200138 ABAN TALUKDAR NAREN TALUKDAR UR 9859404178 DIST.-BARPETA, 781318 NARENGI ASEB COLONY, TYPE IV, 203003 ABANI DOLEY KASHINATH DOLEY SC 7664836895 QTR NO. 4, GHY-26, P.O. NARENGI C/O SALMA STORES, GAR ALI, 202015 ABDUL GHAFOOR ABDUL MANNAN UR 8876215529 JORHAT VILL&P.O.&P.S.:- NIZ-DHING, 206442 ABDUL HANNAN LT. ABDUL MOTALIB UR 9706865304 NAGAON-782123 MAYA PATH, BYE LANE 1A, 203004 ABDUL HAYEE FAKHAR UDDIN UR 7002903504 SIXMILE, GHY-22 H. NO. 4, PEER DARGAH, SHARIF, 203005 ABDUL KALAM ABDUL KARIM UR 9435460827 NEAR ASEB, ULUBARI, GHY 7 HATKHOLA BONGALI GAON, CHABUA TATA GATE, LITTLE AGEL 201309 ABDUL KHAN NUR HUSSAIN KHAN UR 9678879562 SCHOOL ROAD, CHABUA, DIST DIBRUGARH 786184 BIRUBARI SHANTI PATH, H NO. -

Mantraof Perform Or Perish to Be Top Priority for Sarma Government

@guwahatiplus | /c/gplusguwahati www.guwahatiplus.com Volume 08 | Issue 29 May 15 - May 21 , 2021 Price `10 Lightning strike kills 18 jumbos, COVID 19 crisis creates oxygen black Despite official orders Guwahati clinics fingers point towards habitat market in Assam & hospitals run unregulated rates of protection & safety COVID tests INSIDE PG 03 PG 05 PG 07 Mantra of Rise in insurgency, perform or NRC reverification perish to be & CAA execution top priority key challenges for for Sarma CM Himanta G Plus News release, abduction of three ONGC test the nerves of the Bharatiya government employees of which one is still Janata Party (BJP) leader as a chief @guwahatiplus captive with ULFA (I), are cases minister. in point that will surely not NRC is a sensitive issue and ther than managing make the job easier for the newly depending on how the court COVID-19 situation appointed chief minister. responds it will likely trigger PG No in the state, the new Notably, after taking the responses from those who got - 02 chief minister Himanta oath, Sarma in his first media their names in the final list and Biswa Sarma faces interaction called out the the 19 lakhs people who were left Osome critical challenges such as insurgent outfit ULFA Chief out from the final roll. reining in insurgent activities Paresh Barua to shun the path of Sarma is a master strategist, which are raising their ugly head violence and join the mainstream. and his political acumen has so again in Assam, re-verification of Sarma categorically stated far been hardly matched by his the National Register of Citizens that both the government and rivals in Assam. -

Societies Registered Under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the Year 2014-2015

Societies Registered under Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860 for the year 2014-2015 Date of Registratio Registration No. Name of the Society Address District n 03-04-2014 BAK/260/G/01 OF 2014-15 SALBARI CLUSTER, IHDS Vill. Salbari, P.O. & P.S. Salbari-781327 Baksa 03-04-2014 BAK/260/G/02 OF 2014-15 BATHOU ASHRAM, BATHOUPHURI Vill. & P.O. Kataligaon-781372 Baksa 03-04-2014 BAK/260/G/03 OF 2014-15 HIMALAYA SOCIETY, MUSHALPUR Vill. & P.O. Mushalpur Baksa 03-04-2014 BAK/260/G/04 OF 2014-15 DISCOVERY N.G.O. Vill. Chaibari, P.O. Dhanbil Baksa Vill.-Kahibari, P.O.& P.S.-Salbari, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam, 07-04-2014 BAK/260/G/05 OF 2014-15 Peacock Welfare Society Baksa Pin.-781318 Vill.-Choudhurytup, P.O.-Karemura, P.S.-Barbori, Dist.-Baksa 10-04-2014 BAK/260/G/06 OF 2014-15 Minishree Mahila Samity Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781355. Vill.-Saruphulchowki, P.O.-Goreswar, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), 29-04-2014 BAK/260/G/07 OF 2014-15 Nataraj Dance -Acting -Sports Institute Baksa Assam, Pin.-781366. Managing Committee of Daranga Mela Public Water Supply Vill. & P.O.-Daranga Mela, Dist.-Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.- 03-05-2015 BAK/260/G/08 OF 2014-15 Baksa Scheme 781360 Vill.-Jokmari, P.O.-Niz-Defeli, P.S.-Tamulpur, Dist.-Baksa 06-05-2014 BAK/260/G/09 OF 2014-15 Tamulpur Rural Development Society Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781367. Vill.-Sukanjuli, P.O.-No.1 Paharpur, P.S.-Tamulpur, Dist.- 06-05-2014 BAK/260/G/10 OF 2014-15 Sukanjuli Band Dong Committee Baksa Baksa (BTAD), Assam, Pin.-781360. -

Final List of Applications Received for Faculty Positions Against Advt

FINAL LIST OF APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR FACULTY POSITIONS AGAINST ADVT. NO. 18/2015 DT. 18.12.2015 (UPLOADED ON 22.07.2016) F Kindly note that: 1) This is the final list. 2) The applications will be considered for Part-A/B, as the case may be, on the basis of the category of the applicant (SC,ST,OBC, etc.), even if any applicant has not mentioned specifically about the same. Hence no stress is attached on "Part-A/B". *3) All the applications are under the process of screening. Interview for all the positions shall start from August, 2016 onwards (except for Education, which is over on 09.07.2016). Hence applicants are advised to keep an eye on our web notices which will start coming up under the "News & Notifications" page and also in "Recruitment" page. Besides the web notice, short-listed candidates will be intimated through e-mail. 4) Any discrepancy observed may be brought to our notice by sending e-mail to "[email protected]" *5) Also kindly note: No Screening of and interview for shall be conducted for the positions of Associate Professors in the Departments of MBBT and Chemical Sciences, since these are now sub-judice (Updated on 12.09.2016). Serial No Name of Applicant Post Applied For Department / Centre Category Address of the Applicant Remarks Dr. Iswan Jyoti Gogoi, Assistant professor (Contractual), Dept. of Assamese, North Lakhimpur 1 Iswan Jyoti Gogoi Dr. Assistant Professor Assamese Studies OBC College (Autonomous), Khelmati-787031 2 Joyanta Deka Assistant Professor Assamese Studies Gen C/O- Dhani Ram Deka, Vill- Debananda, P.O- Hazarikapara, Dist- Darrang (assam), Pin- 784145 C/O Prof. -

The Bodoland Movementand Its Different Phases

Chapter 4 The Bodoland Movementand Its Different Phases The Bodo movement has been the strongest tribal movement in Assam. This movement seeded during the colonial times and culminated into a radical assertion in the late 1980s. The main source of Bodoland movement was the feeling of discrimination, deprivation and injustice .In the campaign to regain the lost political, economic and cultural suzerainty, the leaders of the Bodo Movement emphasized that the Bodo people are ethnically different from the rest of the people of present day state of Assam and hence entitled to political acknowledgement. The Bodo Movement is the largest movement by the indigenous tribes of Assam so far. It has been shaped by a long trail of events taking place within the Bodo community and in its surrounding social setup. The movement started as one for self-assertion and regeneration of the Bodo community. The Bodo movement was the result of the growth of ethnonationalism in the Bodo Community. The engima of nationalism admittedly defies any cut and dried approach for unravelling its mystery and charm. Nevertheless no one can dispute the fact that the force of nationalism is most compelling and pervasive. Undoubtedly, membership in a nation provides “a powerful means of defining and locating individual selves in the world through the prism of collective personality and its distinctive culture.” At the same time popular mobilization is ignited and set in motion by the driving force of nationalism. Over the years it has been rather evident that the crystallization of national identity on ethnic lines eventually fosters collective identity often decisively and in a manner inconceivable by either religion or class. -

Press Release

Press Release A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) has been signed on the 28th of January, 2021 between Anundoram Borooah Institute of Language, Art and Culture, Assam (ABILAC) and Prachin Bhasha Sanskriti Gaveshana Kendra at Bilasipara, Dhubri, Assam for establishing an Extension Centre of ABILAC to carry out research and other academic activities on the language and culture of Assam, particularly, the lower Assam region.The MoU has been signed by Shri Ashok Singhi, the president on behalf of Prachin Bhasha Sanskriti Gavesana Kendra at Bilasipara, Dhubri, Assam and Professor Dilip Kumar Kalita, Director on behalf of ABILAC in a meeting chaired by Mr. Ashok Singhi and attended by intellectuals, educationists and litterateurs of the area at the Prachin Bhasha Sanskriti Gaveshana Kendra located at Bilasipara town. According to the MoU the Kendra will be known as Prachin Bhasha Sanskriti Gaveshana Kendra, Bilasipara, an Extension Centre of Anundoram Borooah Institute of Language, Art and Culture(ABILAC) Assam. Shri Debojit Chakravarty, the secretary of the Kendra, while stating the objective of the meeting expressed his happiness on the signing of the MoU. He hopes that with the assistance of ABILAC, this center will be able to achieve its objectives. Speaking in the meeting, Professor Dilip Kumar Kalita stated that the center will facilitate research and academic activities on the language and culture of the region by scholars of the region. He stated that ABILAC will look after the academic and administrative activities of the centre while the management of the centre and its property will rest with the local committee. Professor Kalita also stated that ABILAC will help the centre establish a library for the benefit of the scholars and students of the erstwhile Goalpara in particular and lower Assam region in general to carry out research on culture, language, folklore, etc. -

Dhubri Forges Ahead in Development

DECEMBER 2020 Dhubri Forges Ahead in Development Eastern Panorama discovers a massive change in the infrastructural development of Dhubri district, conducted in the recent years and is marching ahead with the road map of all round socio-economic and cultural development, drawn by dynamic and young Deputy Commissioner, Shri Anant Lal Gyani, IAS with innovative ideas and lasting impact for generations to come. 230050 / 230419 (O) Tel No. 03662 { 230303 / 230030 (R) Anant Lal Gyani, IAS Fax No.: 230019 (R) 232760 (O) Deputy Commissioner, Dhubri E-mail : [email protected] Ref. No. ......................................PA-69/2017/257 Date ...........................14-12-2020 MESSAGE It gives me an immense pleasure to learn that the Eastern Panorama, news magazine is going to publish a Coffee Table Booklet reflecting all round developmental activities carried out by the Dhubri District Administration for the last 3 financial years. I hope and believe that this publication would reflect the true scenario of the magnificent developmental works, with various other activities and issues. This publication will also help people to know as how amid challenges and hurdle works of development carried out by all the departments in the district met the highest parameters in the Aspirational District, set by Niti Ayog. Hope, it will bring true picture of works done by PHE, Education, Zilla Parishad, DRDA, Health, PWD, DSWO etc. Activities like water sanitization, proper execution of Cleanliness Drive, proper utilization of MGNREGA fund, United fund, BADP, SDRF Schemes have smoothly been utilized for overall development of Dhubri district. During the time of Covid-19 pandemic also, SOP for Covid-19 had been properly maintained, many awareness programme had been organized to make people aware of this virus and all necessary attempts were made to control the spread of this virus. -

Governor Speech (English) 2021.Pmd

Respected Speaker and Hon’ble Members of the Assam Legislative Assembly, It gives me immense pleasure to address this august house during the February Session, 2021 of the Assam Legislative Assembly. Please accept my greetings on this auspicious occasion. The year 2020 presented us with some unforeseen challenges. The Covid-19 pandemic affected everyone irrespective of one’s position, workplace or location. In these trying times, my Government has shown great alacrity in handling this with steely resolve and fortitude. PPE Kits for frontline COVID warriors were procured and quarantine centres were built in no time. All those affected were promptly provided medical treatment and all those who came in contact of such persons were immediately identified and quarantined. This helped to contain the spread of COVID and has resulted in a high recovery rate and a fairly low morbidity and mortality rate. The tireless efforts of all the Health workers and other frontline workers have contributed tremendously towards slowing down the pandemic. Now, Vaccines are being given to the frontline workers from 16th January, 2021 for free. My Government has also succeeded in containing the economic fallout of COVID-19, and the engines of economic growth are again back at work. Hon’ble Members, it is a matter of great pride that the daughters and sons of our land were conferred with some of 1 the most prestigious civilian awards. Late Shri Tarun Gogoi, was posthumously bestowed with the Padma Bhushan. Also, as many as 8 other individuals namely Lakhimi Baruah, Gopiram Bargayn Burabhakat, Bijoya Chakravarty, Mangal Singh Hazowary, Dulal Manki, Birubala Rabha, Imran Shah and Roman Sarmah from the state were conferred with the Padma Shri. -

1. Hon'ble Speaker Sir, I Now Rise to Present the State Budget for The

1. Hon’ble Speaker Sir, I now rise to present the State budget for the financial year 2014 – 15. 2.1 Economic Environment Before I proceed to present my budget proposals, I would like to apprise the Hon’ble Members of this August House about the overall economic environment and financial position of the State. The global economic growth came down from 3.2% in 2012 to 2.9% in 2013. Growth rate of India, however, has shown some improvement to 4.7%, in 2013-14 from 4.5% in 2012-13. I am happy to inform this August House that the projected growth rate of Assam for 2013-14 is 6.88% which was 5.87% for 2012-13 as per the latest Central Statistical Organization estimates. This is considerably higher than the national average and many other States. Contrary to the trend elsewhere of expenditure compression, our State is in a comfortable position to add further momentum to development activities. This has been possible because of our prudent financial management. According to advance estimate for 2013-14, the per capita income has registered a growth rate of 4.63 percent at constant prices and 14.53 percent at current prices in 2013-14 over the previous year. Our per capita Net State Domestic Product stood at Rs.46,354 in 2013 – 14 compared to National per capita income of Rs. 74,920 during the same period. Therefore, all out effort is required to be taken to bring our per capita income to the National level. 2.2 State Finances Our State finances have been stable for about last ten years.