747 - 400 Flight Crew Training Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pitot-Static System Blockage Effects on Airspeed Indicator

The Dramatic Effects of Pitot-Static System Blockages and Failures by Luiz Roberto Monteiro de Oliveira . Table of Contents I ‐ Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 II ‐ Pitot‐Static Instruments…………………………………………………………………………………………..3 III ‐ Blockage Scenarios – Description……………………………..…………………………………….…..…11 IV ‐ Examples of the Blockage Scenarios…………………..……………………………………………….…15 V ‐ Disclaimer………………………………………………………………………………………………………………50 VI ‐ References…………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……..……51 Please also review and understand the disclaimer found at the end of the article before applying the information contained herein. I - Introduction This article takes a comprehensive look into Pitot-static system blockages and failures. These typically affect the airspeed indicator (ASI), vertical speed indicator (VSI) and altimeter. They can also affect the autopilot auto-throttle and other equipment that relies on airspeed and altitude information. There have been several commercial flights, more recently Air France's flight 447, whose crash could have been due, in part, to Pitot-static system issues and pilot reaction. It is plausible that the pilot at the controls could have become confused with the erroneous instrument readings of the airspeed and have unknowingly flown the aircraft out of control resulting in the crash. The goal of this article is to help remove or reduce, through knowledge, the likelihood of at least this one link in the chain of problems that can lead to accidents. Table 1 below is provided to summarize -

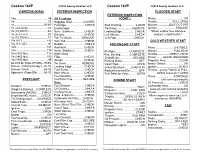

Cessna 182P ©2010 Axenty Aviation LLC Cessna 182P ©2010 Axenty Aviation LLC V SPEEDS (KIAS) EXTERIOR INSPECTION FLOODED START EXTERIOR INSPECTION Vso

Cessna 182P ©2010 Axenty Aviation LLC Cessna 182P ©2010 Axenty Aviation LLC V SPEEDS (KIAS) EXTERIOR INSPECTION FLOODED START EXTERIOR INSPECTION Vso..........................................48 Aft Fuselage (CONT.) Master....................................ON Vs............................................53 Baggage Door..............LOCKED Throttle....................FULL OPEN Vr.......................................50-60 Fuselage.........................CHECK Stall Warning...................CLEAR Mixture................IDLE CUT OFF Vx (sea level)..........................59 Empennage Tie Down.....................REMOVE Ignition.........................ENGAGE Vx (10,000 ft.).........................63 Horiz. Stabilizer..............CHECK Leading Edge.................CHECK *When engine fires advance Vy (sea level)..........................80 Elevator..........................CHECK Left Aileron.....................CHECK mixture, retard throttle* Vy (10,000 ft.).........................73 Tail Tie-Down..............REMOVE Left Flap........................CHECK Vfe (10°)................................140 Trim Tab.........................CHECK COLD WEATHER START Vfe (10°-40°)...........................95 Rudder............................CHECK PRE-ENGINE START Vno........................................141 Antennas........................CHECK Prime.........................6-8 TIMES Vne........................................176 Horiz. Stabilizer..............CHECK Preflight...................COMPLETE Mixture......................FULL RICH -

DHC-8-402, G-FLBE No & Type of Engines

AAIB Bulletin G-FLBE AAIB-26260 SERIOUS INCIDENT Aircraft Type and Registration: DHC-8-402, G-FLBE No & Type of Engines: 2 Pratt & Whitney Canada PW150A turboprop engines Year of Manufacture: 2009 (Serial no: 4261) Date & Time (UTC): 14 November 2019 at 1950 hrs Location: In-flight from Newquay Airport to London Heathrow Airport Type of Flight: Commercial Air Transport (Passenger) Persons on Board: Crew - 4 Passengers - 59 Injuries: Crew - None Passengers - None Nature of Damage: Aileron cable broke Commander’s Licence: Airline Transport Pilot’s Licence Commander’s Age: 51 years Commander’s Flying Experience: 8,778 hours (of which 5,257 were on type) Last 90 days - 150 hours Last 28 days - 33 hours Information Source: AAIB Field Investigation Synopsis Shortly after takeoff in a strong crosswind, the pilots noticed that both handwheels1 were offset to the right in order to maintain wings level flight. The aircraft diverted to Exeter Airport where it made an uneventful landing. The handwheel offset was the result of a break in a left aileron cable that ran along the wing rear spar. In the course of this investigation it was discovered that the right aileron on G-FLBE, and other aircraft in the operator’s fleet, would occasionally not respond to the movement of the handwheels. Non-reversible filters were also fitted to the operator’s aircraft that meant that it was not always possible to reconstruct the actual positions of the control wheel, column or rudder pedals recorded by the Flight Data Recorder. The aircraft manufacturer initiated safety actions to improve the maintenance of control cables and to determine the extent of the unresponsive ailerons across the fleet. -

CAAM 3 Report

3rd Technical Report On Propulsion System and Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) Related Aircraft Safety Hazards A joint effort of The Federal Aviation Administration and The Aerospace Industries Association March 30, 2017 Questions concerning distribution of this report should be addressed to: Federal Aviation Administration Manager, Engine and Propeller Directorate. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents iii List of Figures v I. Foreword 1 II. Background 1 III. Scope 2 IV. Discussion 3 V. Relationship to Previous CAAM Data 7 VI. General Notes and Comments 8 VII. Fleet Utilization 11 VIII. CAAM3 Team Members 12 IX. Appendices List of Appendices 13 Appendix 1: Standardized Aircraft Event Hazard Levels and Definitions 14 • General Notes Applicable to All Event Hazard Levels 19 • Rationale for Changes in Severity Classifications 19 • Table 1. Historical Comparison of Severity Level Descriptions and Rationale for CAAM3 Changes 21 Appendix 2: Event Definitions 39 Appendix 3: Propulsion System and Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) Related Aircraft Safety Hazards (2001 through 2012) 44 • Uncontained Blade 44 • Uncontained Disk 50 • Uncontained – Other 56 iii • Uncontained – All Parts 62 • High Bypass Comparison by Generation 63 • Relationship Among High Bypass Fleet 64 • Case Rupture 66 • Case Burnthrough 69 • Under-Cowl Fire 72 • Strut/Pylon Fire 76 • Fuel Leak 78 • Engine Separation 82 • Cowl Separation 85 • Propulsion System Malfunction Recognition and Response (PSMRR) 88 • Crew Error 92 • Reverser/Beta Malfunction – In-Flight Deploy 96 • Fuel Tank Rupture/Explosion 99 • Tailpipe Fire 102 • Multiple-Engine Powerloss – Non-Fuel 107 • Multiple-Engine Powerloss – Fuel-Related 115 • Fatal Human Ingestion / Propeller Contact 120 • IFSD Snapshot by Hazard Level – 2012 Data Only 122 • RTO Snapshot by Hazard Level – 2012 Data Only 123 • APU Events 123 • Turboprop Events 124 • Matrices of Event Counts, Hazard Ratios and Rates 127 • Data Comparison to Previous CAAM Data 135 [ The following datasets which were collected in CAAM2 were not collected in CAAM3. -

Aircraft Engine Performance Study Using Flight Data Recorder Archives

Aircraft Engine Performance Study Using Flight Data Recorder Archives Yashovardhan S. Chati∗ and Hamsa Balakrishnan y Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02139, USA Aircraft emissions are a significant source of pollution and are closely related to engine fuel burn. The onboard Flight Data Recorder (FDR) is an accurate source of information as it logs operational aircraft data in situ. The main objective of this paper is the visualization and exploration of data from the FDR. The Airbus A330 - 223 is used to study the variation of normalized engine performance parameters with the altitude profile in all the phases of flight. A turbofan performance analysis model is employed to calculate the theoretical thrust and it is shown to be a good qualitative match to the FDR reported thrust. The operational thrust settings and the times in mode are found to differ significantly from the ICAO standard values in the LTO cycle. This difference can lead to errors in the calculation of aircraft emission inventories. This paper is the first step towards the accurate estimation of engine performance and emissions for different aircraft and engine types, given the trajectory of an aircraft. I. Introduction Aircraft emissions depend on engine characteristics, particularly on the fuel flow rate and the thrust. It is therefore, important to accurately assess engine performance and operational fuel burn. Traditionally, the estimation of fuel burn and emissions has been done using the ICAO Aircraft Engine Emissions Databank1. However, this method is approximate and the results have been shown to deviate from the measured values of emissions from aircraft in operation2,3. -

AVIATION INVESTIGATION REPORT A15Q0075 Runway Overrun

AVIATION INVESTIGATION REPORT A15Q0075 Runway overrun WestJet Boeing 737-6CT, C-GWCT Montréal/Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport, Quebec 05 June 2015 Transportation Safety Board of Canada Place du Centre 200 Promenade du Portage, 4th floor Gatineau QC K1A 1K8 819-994-3741 1-800-387-3557 www.tsb.gc.ca [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, 2017 Aviation Investigation Report A15Q0075 Cat. No. TU3-5/15-0075E-PDF ISBN 978-0-660-08454-1 This report is available on the website of the Transportation Safety Board of Canada at www.tsb.gc.ca Le présent rapport est également disponible en français. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. Aviation Investigation Report A15Q0075 Runway overrun WestJet Boeing 737-6CT, C-GWCT Montréal/Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport, Quebec 05 June 2015 Summary On 05 June 2015, a WestJet Boeing 737-6CT (registration C-GWCT, serial number 35112) was operating as flight 588 on a scheduled flight from Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario, to Montréal/Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport, Quebec. At 1457 Eastern Daylight Time, the aircraft touched down in heavy rain showers about 2550 feet beyond the threshold of Runway 24L and did not stop before reaching the end of the runway. The aircraft departed the paved surface at a ground speed of approximately 39 knots and came to rest on the grass, approximately 200 feet past the end of the runway. -

Runway Excursion During Landing, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086, Boeing MD-88, N909DL, New York, New York, March 5, 2015

Runway Excursion During Landing Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 Boeing MD-88, N909DL New York, New York March 5, 2015 Accident Report NTSB/AAR-16/02 National PB2016-104166 Transportation Safety Board NTSB/AAR-16/02 PB2016-104166 Notation 8780 Adopted September 13, 2016 Aircraft Accident Report Runway Excursion During Landing Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 Boeing MD-88, N909DL New York, New York March 5, 2015 National Transportation Safety Board 490 L’Enfant Plaza, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20594 National Transportation Safety Board. 2016. Runway Excursion During Landing, Delta Air Lines Flight 1086, Boeing MD-88, N909DL, New York, New York, March 5, 2015. Aircraft Accident Report NTSB/AAR-16/02. Washington, DC. Abstract: This report discusses the March 5, 2015, accident in which Delta Air Lines flight 1086, a Boeing MD-88 airplane, N909DL, was landing on runway 13 at LaGuardia Airport, New York, New York, when it departed the left side of the runway, contacted the airport perimeter fence, and came to rest with the airplane’s nose on an embankment next to Flushing Bay. The 2 pilots, 3 flight attendants, and 98 of the 127 passengers were not injured; the other 29 passengers received minor injuries. The airplane was substantially damaged. Safety issues discussed in the report relate to the use of excessive engine reverse thrust and rudder blanking on MD-80 series airplanes, the subjective nature of braking action reports, the lack of procedures for crew communications during an emergency or a non-normal event without operative communication systems, inaccurate passenger counts provided to emergency responders following an accident, and unclear policies regarding runway friction measurements and runway condition reporting. -

Propeller Operation and Malfunctions Basic Familiarization for Flight Crews

PROPELLER OPERATION AND MALFUNCTIONS BASIC FAMILIARIZATION FOR FLIGHT CREWS INTRODUCTION The following is basic material to help pilots understand how the propellers on turbine engines work, and how they sometimes fail. Some of these failures and malfunctions cannot be duplicated well in the simulator, which can cause recognition difficulties when they happen in actual operation. This text is not meant to replace other instructional texts. However, completion of the material can provide pilots with additional understanding of turbopropeller operation and the handling of malfunctions. GENERAL PROPELLER PRINCIPLES Propeller and engine system designs vary widely. They range from wood propellers on reciprocating engines to fully reversing and feathering constant- speed propellers on turbine engines. Each of these propulsion systems has the similar basic function of producing thrust to propel the airplane, but with different control and operational requirements. Since the full range of combinations is too broad to cover fully in this summary, it will focus on a typical system for transport category airplanes - the constant speed, feathering and reversing propellers on turbine engines. Major propeller components The propeller consists of several blades held in place by a central hub. The propeller hub holds the blades in place and is connected to the engine through a propeller drive shaft and a gearbox. There is also a control system for the propeller, which will be discussed later. Modern propellers on large turboprop airplanes typically have 4 to 6 blades. Other components typically include: The spinner, which creates aerodynamic streamlining over the propeller hub. The bulkhead, which allows the spinner to be attached to the rest of the propeller. -

Design and Analysis of Advanced Flight: Planning Concepts

NASA Contractor Report 4063 Design and Analysis of Advanced Flight: Planning Concepts Johri A. Sorerisen CONrRACT NAS1- 17345 MARCH 1987 NASA Contractor Report 4063 Design and Analysis of Advanced Flight Planning Concepts John .A. Sorensen Analytical Mechanics Associates, Inc. Moantain View, California Prepared for Langley Research Center under Contract NAS 1- 17345 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Branch 1987 F'OREWORD This continuing effort for development of concepts for generating near-optimum flight profiles that minimize fuel or direct operating costs was supported under NASA Contract No. NAS1-17345, by Langley Research Center, Hampton VA. The project Technical Monitor at Langley Research Center was Dan D. Vicroy. Technical discussion with and suggestions from Mr. Vicroy, David H. Williams, and Charles E. Knox of Langley Research Center are gratefully acknowledged. The technical information concerning the Chicago-Phoenix flight plan used as an example throughout this study was provided by courtesy of United Airlines. The weather information used to exercise the experimental flight planning program EF'PLAN developed in this study was provided by courtesy of Pacific Southwest Airlines. At AMA, Inc., the project manager was John A. Sorensen. Engineering support was provided by Tsuyoshi Goka, Kioumars Najmabadi, and Mark H, Waters. Project programming support was provided by Susan Dorsky, Ann Blake, and Casimer Lesiak. iii DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF ADVANCED FLIGHT PLANNING CONCEPTS John A. Sorensen Analytical Mechanics Associates, Inc. SUMMARY The Objectives of this continuing effort are to develop and evaluate new algorithms and advanced concepts for flight management and flight planning. This includes the minimization of fuel or direct operating costs, the integration of the airborne flight management and ground-based flight planning processes, and the enhancement of future traffic management systems design. -

Guidance for the Implementation of Fdm Precursors

EUROPEAN OPERATORS FLIGHT DATA MONITORING WORKING GROUP B SAFETY PROMOTION Good Practice document GUIDANCE FOR THE IMPLEMENTATION OF FDM PRECURSORS June 2019 Rev 02 Guidance for the Implementation of FDM Precursors | Rev 02 Contents Table of Revisions .............................................................................................................................5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................6 Occurrence Reporting and FDM interaction ............................................................................................ 6 Precursor Description ................................................................................................................................ 6 Methodology for Flight Data Monitoring ................................................................................................. 9 Runway Excursions (RE) ..................................................................................................................11 RE01 – Incorrect Performance Calculation ............................................................................................. 12 RE02 – Inappropriate Aircraft Configuration .......................................................................................... 14 RE03 – Monitor CG Position .................................................................................................................... 16 RE04 – Reduced Elevator Authority ....................................................................................................... -

Modeling with Robotran the Autonomous Electrical Taxi and Pushback Operations of an Airbus A320

Modeling with Robotran the autonomous electrical taxi and pushback operations of an Airbus A320 Dissertation presented by Stéphane QUINET for obtaining the Master’s degree in Electro-mechanical Engineering Option(s): Mechatronics Supervisor(s) Paul FISETTE , Bruno DEHEZ Reader(s) Francis LABRIQUE, Matthieu DUPONCHEEL Academic year 2016-2017 Acknowledgements Before getting to the heart of this master thesis, I wish to take the time to thank the many people that supported me in this project of going back studying at 26 years old and making it possible to combine both my passion for flying and for acquiring new technical knowledge. I would like to thank my master thesis supervisors, Pr. Paul Fisette and Pr. Bruno Dehez for their support and for the approval to work on this proposed subject. It was a chance to be sup- ported by people with such an open-mindedness and eagerness to discover new technical fields. Their understanding of my challenging situation and their flexibility was greatly appreciated. I would especially like to thank Nicolas Docquier for the many hours spent at correcting the Robotran-Simulink interface Windows version, my algorithms and for the countless advises that he provided all along the year. Thanks to the assisting staff of the department, Aubain Verlé, Olivier Lantsoght, Quentin Docquier for their technical inputs and support. Finally, thank you very much to UCL university staff for their understanding and their support during those 5 years. After those 5 challenging years combining University and my airline pilot job, it is time to thank the most important person who makes all of this possible, my companion, Carole Aerts. -

Delta Air Lines Flight 1086 ALPA Submission

Submission of the Air Line Pilots Association, International to the National Transportation Safety Board Regarding the Accident Involving Delta Air Lines 1086 MD-88 DCA15FA085 New York, NY March 5, 2015 Air Line Pilots Association, International Delta Air Lines 1086 Submission Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.0 Factual Information ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 History of Flight ............................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Operations .............................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Weather ........................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Regulations for Dispatching an Aircraft ........................................................................... 5 2.3 Crew Expectation of Runway Condition .......................................................................... 6 2.4 Approach ......................................................................................................................... 6 2.5 Landing Distance Assessment .......................................................................................... 7 2.6 Runway Condition on the Pier ........................................................................................