The Prison-Industrial Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a New Identity: Race, Gangs, and Violence in California Prisons

\\jciprod01\productn\M\MIA\66-3\MIA301.txt unknown Seq: 1 23-APR-12 13:53 Building a New Identity: Race, Gangs, and Violence in California Prisons DALE NOLL* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 847 R II. BACKGROUND ....................................................... 850 R A. California Prison Populations...................................... 850 R B. Pre-Johnson Housing Process ...................................... 851 R C. Prison Gangs and Racial Makeup .................................. 852 R D. Racial Identification in Prison as a Social Construct .................. 853 R E. Race-Related Violence in California Prisons ......................... 855 R F. Johnson v. California ............................................. 856 R G. Duty to Inmates ................................................. 857 R H. CDC Reaction to Johnson – The Updated Housing Policy .............. 858 R I. The Texas Experience – Equal Status Contact Theory ................. 859 R III. DISCUSSION ......................................................... 860 R A. Use of Race as a Category Flawed ................................. 860 R B. Gang Identities Used to Promote White Supremacy .................... 862 R C. The Concept of Racially Motivated Violence is Skewed ................ 864 R D. Using Segregation to Prevent Violence is Illogical .................... 866 R E. Impact of Segregation in Prisons ................................... 870 R F. Was Johnson v. California a Liberal Victory? ....................... -

Building a Movement in the Non-Profit Industrial Complex

Building A Movement In The Non-Profit Industrial Complex Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michelle Oyakawa Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Korie Edwards, Advisor Andrew Martin Steve Lopez Copyrighted by Michelle Mariko Oyakawa 2017 Abstract Today, democracy in the United States is facing a major challenge: Wealthy elites have immense power to influence election outcomes and policy decisions, while the political participation of low-income people and racial minorities remains relatively low. In this context, non-profit social movement organizations are one of the key vehicles through which ordinary people can exercise influence in our political system and pressure elite decision-makers to take action on matters of concern to ordinary citizens. A crucial fact about social movement organizations is that they often receive significant financial support from elites through philanthropic foundations. However, there is no research that details exactly how non-profit social movement organizations gain resources from elites or that analyzes how relationships with elite donors impact grassroots organizations’ efforts to mobilize people to fight for racial and economic justice. My dissertation aims to fill that gap. It is an ethnographic case study of a multiracial statewide organization called the Ohio Organizing Collaborative (OOC) that coordinates progressive social movement organizations in Ohio. Member organizations work on a variety of issues, including ending mass incarceration, environmental justice, improving access to early childhood education, and raising the minimum wage. In 2016, the OOC registered over 155,000 people to vote in Ohio. -

Covid Public Health & Safety Budget

CALIFORNIA COVID PUBLIC HEALTH & SAFETY BUDGET A BUDGET TO SAVE LIVES 75 2020-2021 Fiscal Year Table Of Contents PAGE 3 Executive Summary PAGE 4 COVID-19 Threatens Public Health and Safety in California Page 4........ COVID-19 is already inside California’s carceral facilities Page 5........ Inhumane conditions put our entire state at risk Page 6........ Immediate action through five key proposals is necessary PAGE 9 Proposal 1: California must reduce its jail population Page 9........ Counties must reduce pretrial incarceration Page 10........ Counties must conduct post-conviction re-sentencing and vacations of judgment Page 11........ Counties must reduce harm inside of jails PAGE 12 Proposal 2: California must reduce its prison population PAGE 14 Proposal 3: California must reduce its immigrant detention population Page 14........ California can and must adopt a moratorium on all transfers to ICE Page 15........ California can and must halt the expansion of immigration detention facilities PAGE 16 Proposal 4: California must decriminalize and decarcerate its youth Page 16........ Youth can’t get well in a cell Page 17........ California must collect better data Page 18........ California must prioritize youth diversion Page 18........ California must divest from youth incarceration Page 20........ California must advance decriminalization Page 20........ California must decarcerate our youth Page 21........ Students need college preparation, not prison preparation Page 22........ Youth deserve cash assistance and other access to income PAGE 24 Proposal 5: Create and Fund Opportunities for Local Governments to Implement Community-Based Systems of Health, Reentry, and Alternatives to Incarceration Page 24........ Less People in the Jails Equals a Cost Savings Page 25....... -

Dynamics of Financialization After the Crisis? How Finance (Still) Gets Its Way

Dynamics of financialization after the crisis? How finance (still) gets its way Julie Froud Manchester Business School and Centre for Research in Socio‐Cultural Change (CRESC), UK Outline • Starting point: finance is not humbled, (despite current crisis, the resulting bailouts and large losses imposed in terms of foregone GDP and imposed austerity). But growing concerns about ‘imbalance’ • Explaining this as a story about power and elites, mainly about the UK (noting specificities of financialization), but with relevance elsewhere, by: a) looking back at C Wright Mills and b) moving forward with the finance and point value complex. • The aim is to highlight the pervasive, programmatic power of finance. To understand financialization, we have to understand many things. So, a contribution to a collective endeavour. (1) Finance unreformed The story so far… Unreformed finance a) investment banking • Half‐hearted reform in UK: limited structural change ‐> no major bank break‐up; ring fencing of investment banking, not separation; few constraints on long chain leveraged finance; (still) low capital requirements; bonuses survive (eg HSBC Feb 2014) and redundancies postponed • Scandals continue: Libor, exchange rate fixing (even after Libor) Collusion, manipulation of rates ‐> profit and bonus implications; Barclays Capital as ‘loose federation of money making franchises’ (not the ‘go‐to bank’). Finance Minister, George Osborne on Libor crisis: ‘we know what went wrong’…. No interest in learning. Unreformed finance b) retail banking • Half‐hearted reform in UK: more competition via ‘challenger banks’… (but not tackling business model, where RoE targets in mid‐teens drive mis‐selling eg Jenkins at Barclays: 15% RoE target in retail) • Scandals continue: ever more mis‐selling. -

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Institution abbreviation, City, State and zip code. Prison Name Abbreviation City State Zip Avenal State Prison ASP Avenal CA 93204 California City Correctional Center CAC California City CA 93505 California State Prison, Calipatria CAL Calipatria CA 92233 California Correctional Center CCC Susanville CA 96130 California Correctional Institution CCI Tehachapi CA 93561 Centinela State Prison CEN Imperial CA 92251 Central California Women’s Facility CCWF Chowchilla CA 93610 California Health Care Facility CHCF Stockton CA 95215 California Institution for Men CIM Chino CA 91710 California Institution for Women CIW Corona CA 92878 California Men's Colony CMC San Luis Obispo CA 93409 California Medical Facility CMF Vacaville CA 95696 California State Prison, Corcoran COR Corcoran CA 93212 California Rehabilitation Center CRC Norco CA 92860 Correctional Training Facility CTF Soledad CA 93960 Chuckawalla Valley State Prison CVSP Blythe CA 92225 Deuel Vocational Institute DVI Tracy CA 95376 Folsom State Prison FSP Represa CA 95671 High Desert State Prison HDSP Susanville CA 96127 Ironwood State Prison ISP Blythe CA 92225 Kern Valley State Prison KVSP Delano CA 93216 California State Prison, Lancaster LAC Lancaster CA 93536 Mule Creek State Prison MCSP Ione CA 95640 North Kern State Prison NKSP Delano CA 93215 Pelican Bay State Prison PBSP Crescent City CA 95531 Pleasant Valley State Prison PVSP Coalinga CA 93210 RJ Donovan Correctional Facility RJD San Diego CA 92179 California State Prison, Sacramento SAC Represa CA 95671 Substance Abuse Treatment Facility SATF Corcoran CA 93212 Sierra Conservation Center SCC Jamestown CA 95327 California State Prison, Solano SOL Vacaville CA 95696 San Quentin SQ San Quentin CA 94964 Salinas Valley State Prison SVSP Soledad CA 93960 Valley State Prison VSP Chowchilla CA 93610 Wasco State Prison WSP Wasco CA 93280 N.A. -

State of California California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Adult Programs

STATE OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION ADULT PROGRAMS Annual Report Division of Addiction and Recovery Services June 2009 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Division of Addiction and Recovery Services (DARS) is to provide evidence-based substance use disorder treatment services to California’s inmates and parolees. CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS AND REHABILITATION ADULT PROGRAMS DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES MATTHEW L. CATE SECRETARY KATHRYN P. JETT UNDERSECRETARY, ADULT PROGRAMS C. ELIZABETH SIGGINS CHIEF DEPUTY SECRETARY (Acting), ADULT PROGRAMS THOMAS F. POWERS DIRECTOR DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES SHERRI L. GAUGER DEPUTY DIRECTOR DIVISION OF ADDICTION AND RECOVERY SERVICES ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was prepared by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations’ (CDCR) Division of Addiction and Recovery Services’ (DARS) Data Analysis and Evaluation Unit (DAEU) with assistance from Steven Chapman, Ph.D., Assistant Secretary, Office of Research. It provides an initial summary of performance indicators, demographics and background information on the DARS Substance Abuse Treatment Programs. The information presented in this report is designed to assist the treatment programs and institutional staff in assessing progress, identifying barriers and weaknesses to effective programming, and analyzing trends, while establishing baseline points to measure outcomes. Under the direction of Bill Whitney, Staff Services Manager II; Gerald Martin, Staff Services Manager I; Sheeva Sabati, Research Analyst II; Ruben Mejia, Research Program Specialist; Krista Christian, Research Program Specialist, conducted extensive research and analysis for this report. Peggy Bengs, Information Officer II and Norma Pate, Special Assistant to the Deputy Director, DARS provided editorial contributions. NOTE: In 2007, DARS designed the Offender Substance Abuse Treatment Database to monitor and evaluate programs. -

Hustle and Flow: Prison Privatization Fueling the Prison Industrial Complex

FULCHER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 6/10/2012 2:43 PM Hustle and Flow: Prison Privatization Fueling the Prison Industrial Complex Patrice A. Fulcher* ABSTRACT The Prison Industrial Complex (“PIC”) is a profiteering system fueled by the economic interests of private corporations, federal and state correctional institutions, and politicians. The PIC grew from ground fertilized by an increase in the U.S. prison population united with an economically depressed market, stretched budgets, and the ineffective allocation of government resources. The role of the federal, state, and local governments in the PIC has been to allocate resources. This is the first of a series of articles exploring issues surrounding the PIC, including (1) prison privatization, (2) outsourcing the labor of prisoners for profit, and (3) constitutional misinterpretations. The U.S. prison population increased in the 1980s, in part, because of harsh drug and sentencing laws and the racial profiling of Blacks. When faced with the problem of managing additional inmates, U.S. correctional institutions looked to the promise of private prison companies to house and control inmates at reduced costs. The result was the privatization of prisons, private companies handling the management of federal and state inmates. This Article addresses how the privatization of prisons helped to grow the PIC and the two ways in which governments’ expenditure of funds to private prison companies amount to an inefficient allocation of resources: (1) it creates an incentive to increase the prison population, which led to a monopoly and manipulation of the market by Correction Corporation of America (“CCA”) and The GEO Group, Inc. -

Gangs Beyond Borders

Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Gangs Beyond Borders California and the Fight Against Transnational Organized Crime March 2014 Kamala D. Harris California Attorney General Message from the Attorney General California is a leader for international commerce. In close proximity to Latin America and Canada, we are a state laced with large ports and a vast interstate system. California is also leading the way in economic development and job creation. And the Golden State is home to the digital and innovation economies reshaping how the world does business. But these same features that benefit California also make the state a coveted place of operation for transnational criminal organizations. As an international hub, more narcotics, weapons and humans are trafficked in and out of California than any other state. The size and strength of California’s economy make our businesses, financial institutions and communities lucrative targets for transnational criminal activity. Finally, transnational criminal organizations are relying increasingly on cybercrime as a source of funds – which means they are frequently targeting, and illicitly using, the digital tools and content developed in our state. The term “transnational organized crime” refers to a range of criminal activity perpetrated by groups whose origins often lie outside of the United States but whose operations cross international borders. Whether it is a drug cartel originating from Mexico or a cybercrime group out of Eastern Europe, the operations of transnational criminal organizations threaten the safety, health and economic wellbeing of all Americans, and particularly Californians. -

Case 4:94-Cv-02307-CW Document 2996-2 Filed 07/14/20 Page 1 of 360

Case 4:94-cv-02307-CW Document 2996-2 Filed 07/14/20 Page 1 of 360 1 DONALD SPECTER – 083925 RITA K. LOMIO – 254501 2 MARGOT MENDELSON – 268583 PRISON LAW OFFICE 3 1917 Fifth Street Berkeley, California 94710-1916 4 Telephone: (510) 280-2621 Facsimile: (510) 280-2704 5 MICHAEL W. BIEN – 096891 6 GAY C. GRUNFELD – 121944 THOMAS NOLAN – 169692 7 PENNY GODBOLD – 226925 MICHAEL FREEDMAN – 262850 8 ROSEN BIEN GALVAN & GRUNFELD LLP 9 101 Mission Street, Sixth Floor San Francisco, California 94105-1738 10 Telephone: (415) 433-6830 Facsimile: (415) 433-7104 11 LINDA D. KILB – 136101 12 DISABILITY RIGHTS EDUCATION & DEFENSE FUND, INC. 13 3075 Adeline Street, Suite 201 Berkeley, California 94703 14 Telephone: (510) 644-2555 Facsimile: (510) 841-8645 15 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 16 17 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 18 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 19 20 JOHN ARMSTRONG, et al., Case No. C94 2307 CW 21 Plaintiffs, [REDACTED] DECLARATION OF PATRICK BOOTH IN SUPPORT OF 22 v. PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO PROTECT ARMSTRONG CLASS 23 GAVIN NEWSOM, et al., MEMBERS DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC 24 Defendants. Judge: Claudia Wilken 25 26 27 28 Case No. C94 2307 CW DECLARATION OF PATRICK BOOTH IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION TO PROTECT ARMSTRONG [3577254.1] CLASS MEMBERS DURING COVID-19 PANDEMIC Case 4:94-cv-02307-CW Document 2996-2 Filed 07/14/20 Page 2 of 360 1 I, Patrick Booth, declare: 2 1. I am an attorney licensed to practice before the courts of the State of 3 California. I am also an attorney at the Prison Law Office, counsel of record in Armstrong 4 v. -

Austrian Theorizing: Recalling the Foundations

AUSTRIAN THEORIZING: RECALLING THE FOUNDATIONS WALTER BLOCK t is a pleasure to reply to Caplan’s (1999) critique of Austrian economics. Unlike other such recent reactions1 this one shows evidence of great familiarity with the IAustrian (praxeological) literature, and a deep interest in its analytical foundations. Thus, Caplan correctly identifies the works of Ludwig von Mises and Murray N. Rothbard as the core of what sets Austrian economics apart from the neoclassical mainstream. And he insightfully relegates the writings of F.A. Hayek and Israel M. Kirzner to an intermediate position between the praxeological and neoclassical approaches.2 We shall defend this core of Austrian economics against Caplan’s criticisms, and show that, just as in the case of these others, his arrows fall wide of their mark. It is nevertheless instructive to highlight his errors. The benefits are a better understanding of the Austrian School, and greater insight into neoclassical short- comings. This article follows the outline of Caplan (1999) and is divided into the same four sections as his: first an introduction, second, consumer theory, third, welfare economics, and fourth, a conclusion. WALTER BLOCK is economics department chairman and professor at the University of Cen- tral Arkansas, Conway. The author would like to thank Guido Hülsmann and Michael Levin for helpful comments to an earlier draft of this paper. He would also like to thank an anony- mous referee who made no fewer than seven suggestions, all of which were incorporated into this paper, much to its improvement. All remaining errors are, of course, my responsibil- ity. 1See in this regard Rosen (1997), Tullock (1998), Timberlake (1987), Demsetz (1997), Yeager (1987) and Krugman (1998). -

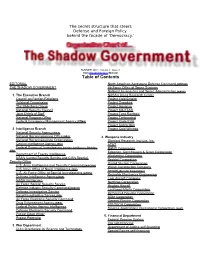

Table of Contents

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

Ad Law Incarcerated Giovanna Shay

Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law Volume 14 | Issue 2 Article 1 2010 Ad Law Incarcerated Giovanna Shay Recommended Citation Giovanna Shay, Ad Law Incarcerated, 14 Berkeley J. Crim. L. 329 (2010). Available at: http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/bjcl/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals and Related Materials at Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Berkeley Journal of Criminal Law by an authorized administrator of Berkeley Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shay: Ad Law Incarcerated Ad Law Incarcerated Giovanna Shayt INTRODUCTION: THE REGULATION OF "MASS INCARCERATION" 1 The United States has over two million prisoners, 2 the largest incarcerated population worldwide. 3 Our nation has been described as a "carceral state" with a policy of "mass imprisonment, '4 and our vast prison system has been termed a "prison industrial complex." 5 Massive growth in the prison t Assistant Professor of Law, Western New England College School of Law. Thanks are due to Ty Alper, Bridgette Baldwin, Rachel Barkow, John Boston, Erin Buzuvis, Jamie Fellner, Amy Fettig, James Forman, Jr., Lisa Freeman, Betsy Ginsberg, Valerie Jenness, Johanna Kalb, Diana Kasdan, Christopher N. Lasch, Art Leavens, Dori Lewis, Jerry Mashaw, Michael Mushlin, Alexander Reinert, Andrea Roth, Melissa Rothstein, Margo Schlanger, Sudha Setty, Robert Tsai, and the Feminist Legal Theory Workshop at Emory School of Law, especially Martha Fineman and Pamela Bridgewater, for inviting me to participate, and Kim Buchanan, Kristin Bumiller, Brett Dignam, and Cole Thaler for their comments.