Notes and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walter A. Skya

Japan’s Holy War asia-pacific: culture, politics, and society Editors: Rey Chow, H. D. Harootunian, and Masao Miyoshi WALTER A. SKYA Japan’s Holy War THE IDEOLOGY OF RADICAL SHINTO¯ ULTRANATIONALISM Duke University Press Durham and London 2009 ∫ 2009 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Arno with Magma Compact display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. dedicated to my wife, mariko, daughter, amy, and son, mark Contents acknowledgments ix introduction 1 I. Emperor Ideology and the Debate over State and Sovereignty in the Late Meiji Period 1. From Constitutional Monarchy to Absolutist Theory 33 2. Hozumi Yatsuka: The Religious Völkisch Family-State 53 3. Minobe Tatsukichi: The Secularization of Politics 82 4. Kita Ikki: A Social-Democratic Critique of Absolute Monarchy 112 II. Emperor Ideology and the Debate over State and Sovereignty in the Taish¯o Period 5. The Rise of Mass Nationalism 131 6. Uesugi Shinkichi: The Emperor and the Masses 153 7. Kakehi Katsuhiko: The Japanese Emperor State at the Center of the Shint¯o Cosmology 185 III. Radical Shint¯o Ultranationalism and Its Triumph in the Early Sh¯owa Period 8. Terrorism in the Land of the Gods 229 9. Orthodoxation of a Holy War 262 conclusion 297 notes 329 select bibliography 363 index 379 Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful to a number of scholars in the United States, Japan, and Europe who have taught me and enthusiastically supported me and my research projects over the past two decades. -

Southeast Asia Program

SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM FALL • 1994 BULLETIN • 0 ,., SEAP ARCHIVE COPY ' DO NOT REMOVE FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, This has been a year of many changes in the Southeast Asia Program, some of them sad and others happy. First, the news that is both sad and happy. Randolph Barker's term as director came to an end, and I was elected to take his place as director. At the same time that Randy stepped down, Helen Swank retired. Many of us think of her affectionately as an institution coterminous with the Southeast Asia Program, and after thirty-three years it is hard to conceive of the office without her. Her place was taken by Nancy Stage. Nancy brings back home to Ithaca a range of experience in fund-raising and development from her previous work in Colorado. Helen is a hard act to follow, but Nancy's intelligence and sparkle keep the office an exciting and pleasant place to work or visit. We also had some losses among our faculty. We are sad to announce the passing of two of our most beloved colleagues, Lauriston Sharp and Milton Barnett. Both Lauri and Milt were active in the Southeast Asia Program until a short time before their deaths. Their careers and contributions to SEAP are outlined in the following pages. To honor Lauri, in 1975 we established the Lauriston Sharp Prize for the most outstanding thesis in Southeast Asian studies at Cornell. Winners of this prize have become top scholars in their fields and are active in universities throughout the country. -

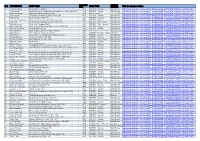

URL De Gruyter Online 1 Frank A

SUBJECT No.2 CONTRIBUTOR SHORT TITLE COPYRIGHT BISAC TITLE YEAR PACKAGE URL De Gruyter Online 1 Frank A. Kierman Chinese Ways in Warfare 1974 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674182059&searchTitles=true 2 Chi-ming Hou Foreign Investment and Economic Development in China, 1840-1937 1965 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674182479&searchTitles=true 3 Richard H. Minear Japanese Tradition and Western Law 1970 LAW / General Law & Political Science http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674182554&searchTitles=true 4 Yen-p'ing Hao Comprador in Nineteenth Century China, The 1970 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674182783&searchTitles=true 5 Han-yi Fêng Chinese Kinship System, The 1967 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674183803&searchTitles=true 6 Johannes Hirschmeier Origins of Entrepreneurship in Meiji Japan, The 1985 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674184336&searchTitles=true 7 Ping-ti Ho Studies on the Population of China, 1368-1953 1959 HISTORY / Asia / China World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674184510&searchTitles=true 8 Marius B. Jansen China in the Tokugawa World 1992 HISTORY / Asia / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674184763&searchTitles=true 9 Kwang-Ching Liu Anglo-American Steamship Rivalry in China, 1862-1874 1962 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674184886&searchTitles=true 10 Arthur N. Holcombe Chinese Revolution, The 1930 HISTORY / General World History http://www.degruyter.com/search?f_0=isbnissn&q_0=9780674184978&searchTitles=true 11 Dorris D. -

THE. /Ourrml OF

THE. /ourrml OF PUBLISHED BY THE ASSOCIATION FOR ASIAN STUDIES, INC Volume XX, Number 1 November 1960 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.229, on 29 Sep 2021 at 04:06:43, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.2307/2050068 THE ASSOCIATION FOR ASIAN STUDIES, INC. Formerly the Far Eastern Association, Inc. OFFICERSOF THE ASSOCIATION W. NORMAN BROWN, President HYMAN KUBLIN, Treasurer University of Pennsylvania Brooklyn College LAURISTON SHARP, Vice-President DELMER M. BROWN, Editor of Monographs, Cornell University University of California ROBERT I. CRANE, Secretary ROGER F. HACKETT, Editor of Journal University of Michigan Northwestern University DIRECTORS VIRGINIA T. ADLOFF (1958-1961) DANIEL H. H. INGALLS (1959-1962) New York City Harvard University JOHN F. CADY (1959-1962) CHARLES O. HUCKER (1960-1963) Ohio University University of Arizona NORTON GINSBURG (1958-1961) ROBERT A. SCALAPINO (1960-1963) University of Chicago University of California JOHN W. HALL (1958-1961) MILTON B. SINGER (1960-1963) University of Michigan University of Chicago DOUGLAS G. HARING (1959-1962) C. MARTIN WILBUR (1958-1961) Syracuse University Columbia University JAMES R. HIGHTOWEK (1960-1963) CHITOSHI YANAGA (1959-1962) Harvard University Yale University JOHN K. FAIRBANK (Honorary) GEORGE B. CRESSEY (Honorary) Harvard University Syracuse University COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN KNIGHT BIGGERSTAFF, Nominating HILARY CONROY, Program Cornell University University of Pennsylvania WARD MOREHOUSE, Membership The Asia Society EDITORS OF THE JOURNAL ROGER F. HACKETT, Editor MYRON WEINER, Assistant Editor Northwestern University University of Chicago ALBERT FEUERWERKER, Associate Editor RHOADS MURPHEY, Book Reviews University of Michigan University of Washington G. -

Institute of Pacific Relations Fonds

Institute of Pacific Relations fonds Compiled by Kate McCandless, Philip Holden, and Laurenda Daniells (1981) Revised by Jane Turner (1990), Marnie Burnham (1996), and Erwin Wodarczak (2004, 2012) Last revised February 2012 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Custodial History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Publications series o Correspondence series o Annual Reports series o Financial series o IPR Conferences series o Senate Investigation series o Tax Evasion Court Case series o Miscellaneous series File List Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description Institute of Pacific Relations fonds. – 1925-1989; predominant 1950-1960. 12.95 m of textual records. ca. 150 photographs: b&w ; 21 x 29 cm. or smaller. 1 album. Administrative History The Institute of Pacific Relations (IPR) was established in 1925 as a private non-partisan forum for the promotion of mutual understanding amongst nations of the Pacific Rim through discussion, research, and education. The IPR's programmes of conferences, research projects, publications, and its quarterly journal Pacific Affairs contributed to the interchange of information in the field of Asian Studies. The Institute conducted its affairs through autonomous national councils, each represented on the Pacific Council, the international governing body which directed the IPR's programmes. The International Secretariat, the Pacific Council's administrative organ, was based in Hawaii until it moved to New York in 1933. The American IPR was of particular importance to the organization due in part to its substantial financial contributions; it also carried out its own programmes of research, conferences, and publishing, the latter including Far Eastern Survey. -

Present Nationalism and Communist Power

RESEARCH PAPERS AND POLICY STUDIES 44 F L' INSTITUTE OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES ~ 'UUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY The Challenge of Change East Asia in the New Millennium EDITED BY David Arase A publication of the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of Califor nia, Berkeley. Although the Institute of East Asian Studies is responsible for the selection and acceptance of manuscripts in this series, responsibil ity for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of statements rests with their authors. Correspondence and manuscripts may be sent to: Ms. Joanne Sandstrom, Managing Editor Institute of East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley, California 94720-2318 E-mail: [email protected] The Research Papers and Policy Studies series is one of several publica tions series sponsored by the Institute of East Asian Studies in conjunc tion with its constituent units. The others include the China Research Monograph series, the Japan Research Monograph series, and the Korea Research Monograph series. A list of recent publications appears at the back of the book. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The challenge of change : East Asia in the new millennium I edited by David Arase. p. em. - (Research papers and policy studies ; 44) Festschrift in honor of Chalmers Johnson. Includes bibliographical references. List of author's works : at end of work. ISBN 1-55729-079-2 (alk. paper) 1. East Asia-Relations-United States. 2. United States Relations-East Asia. 3. Japan-Economic policy-1945- 4. China-Politics and government-1976- I. Title: East Asia in the new millennium. II. Arase, David. III. -

Volume XXXVI, Number I November 1976

THE V OF PUBLISHED BY THE ASSOCIATION FOR ASIAN STUDIES, INC. Volume XXXVI, Number i November 1976 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.219, on 25 Sep 2021 at 18:54:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911800078852 The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. i Lane Hall, The University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Officers of the Association. President: MARIUS B. JANSEN. Princeton University. Vice President: JOHN M E( HOLS. Cornell University. Secretary-Treasurer: RHOADS MURPHEY. University of Michigan. Editor, Journal of Asian Studies: RALPH W. NICHOLAS. University of Chicago. Editor, Monographs, Occasional Papers, and Reference Series: PAUL WHEATLEY. University of Chicago. And the Board of Directors. Board of Directors. President. Vice President, and Secretary-Treasurer; Past President: PING-TI HO. University of Chicago. 1974-1977: DANIEL S. LEV, University of Washington: Tsi'LiN MEI. Cornell University: JOHN MESKILL fat large), Barnard College: ROBERT K SAKAI. University of Hauah: and W HOWARD WRIGGINS, Columbia University. 1975-1978: CAROLYN M. ELLIOTT. Welles/ey College: CHAR- LOTTE FL'RTH (at large), California Slate University, Long Beach: MARLEIGH G. RYAN. University of Iowa; LYMAN P. VAN SLYKE, Stanford University; and PALL WHEATLEY, University of Chicago. 1976-1979: PAUL A. COHEN (at large), Wellesley College; HILDRED GEERTZ, Princeton University; Sl'SAN L. Hi'NT- INGTON. Ohio Slate University; EVELYN S. RAWSKI, University of Pittsburgh; and HIROSHI WAGATSUMA, University of California, Los Angeles. Executive Committee. President, Vice President. Past President, and Secretary-Treasurer; Chair. -

~Lv-LLJ CR.13 (11-64)

- ROUTING SLIP FICHE DE TRANSMISSION TO a A: R~-4~-c . 1 FOR ACTION I POUR SUITE A DONNER FOR APPROVAL POUR APPROBATION FOR SIGNATURE POUR SIGNATURE PREPARE DRAFT PROJET A REDIGER FOR COMMENTS POUR OBSERVATIONS MAY WE CONFER? POURRIONS-NOUS EN PARLER? I YOUR ATTENTION I VOTRE ATTENTION AS DISCUSSED COMME CONVENU ll AS REQUESTED l v SUITE A VOTRE DEMANDE NOTE AND FILE NOTER ET CLASSER NOTE AND RETURN I NOTER ET RETOURNER FOR INFORMATION POUR INFORMATION Date: FROM: DE: ?t> ~~, ~lv-LLJ CR.13 (11-64) - t Mr. Lemieux / with ineOIIing latter Daar Mr. 'l'aJ'1or, 'fbe cretarJ'-(JeMral hu •a4 • to ae la"-, Vit. tbaD, ncetpt of f'O'U' letter of 21 Much 1966 by Whieb you seat bill copiea ot the •stat..at oa Ulli.tect State• Chi• PalleT' aDd other :pa:pen relat.t t o tbe poa1t1011 lupporte4 'b7 198 aahol.ars of Aataa affa1ra. lf'be 8eCN'tal"J'-0eDeral VCNld ll.1Dt J'O\t to kDclr that be bal read theM pa:pera Y1 th snat i lltar.at. 1Ja If. Miller P1"1nc1pal. Officer Mr. Harold Taylor Cba.1me lat1o•l eearch 11 CD Puce Stnateg- ~1 Weat 12th St t 1leV York, I.Y. 1001~ NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL ON PEACE STRATEGY HAROLD TAYLOR, Clwlrman 241 WEST 12TH STREET BETTY I::IOETZ l.ALL., NEW YORK, N.Y. 10014 Vice Chairman OREGON S-3839 MAURICE ALBERTSON EMILE BENOIT Le:WIB BOHN KENNETH BoULOINill DONALD BRENNAN URI£ BRONF"ENBRENNER DAVID CAVERB 1...-( .JAMES CROW ( / KARL DEUTSCH MORTON DEUTSCH FREEMAN DYBON BERNARD FELO v~· RoiliER FisHER .JEROME FRANK ERICH FROMM Be:NTLEY I::ILABB HUOBON HDAiliLANO DAVID INiliLIB WALTER IBARO HERBERT KELMAN RALPH LAPP ARTHUR LARBON HAROLD l.ABBWELL CHAUNCEY LEAKE ROBERT LIF"TON ~ · SEYMOUR MARTIN LIPSET ROLLO MAY MARiliARET MEAD SEYMOUR Me:LMAN DONALD MICHAEL WALTER MILLIS RUBBELL MDRiliAN HANB MORiliENTHAU I::IARONER MURPHY A • .J. -

The Evolution of Regional Awareness and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

THE EVOLUTION OF REGIONAL AWARENESS AND REGIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Malaya ITO MITSUOMI of University FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2017 THE EVOLUTION OF REGIONAL AWARENESS AND REGIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Malaya ITO MITSUOMIof THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY University FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2017 UNIVERSIT MALAYA PERAKUAN KEASLIAN PENULSAN Nama: Ito Mitsuomi No. Pendaftaran/Matrik: AHA100001 Nama Ijazah: Ph.D (Sejarah) Tajuk Disertasi: The Evolution of Regional Awareness and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Bidang Penyelidikan: Regionalism in Southeast Asian Saya dengan sesungguhnya dan sebenarnya mengaku bahawa: (1) Saya adalah satu-satunya pengarang/penulis Hasil Kerja ini; (2) Hasil Kerja ini adalah asli; (3) Apa-apa penggunaan mana-mana Hasil Kerja yang mengandungi hakcipta telah dilakukan secara urusan yang wajar dan bagi maksud yang dibenarkan dan apa- apa petikan, ekstrak, rujukan, atau pengeluaran semula daripada atau kepada mana-mana hasil kerja yang mengandungi hakcipta telah dinyatakan dengan sejelasnya dan secukupnya dan satu pengiktirafan tajuk Hasil Kerja tersebut dan pengarang/penulisnya telah dilakukan di dalam Hasi Kerja ini; (4) Saya tidak menpunyai apa-apa pengetahuan sebenar atau patut semunasabahnya tahu bahawa penghasilan Hasil Kerja ini melanggarMalaya suatu hakcipta Hasil Kerja yang lain; (5) Saya dengan ini menyerahkan kesemuaof dan tiap-tiap hak yang terkandung di -

A History of Asia 7Th Edition Free Download

FREE A HISTORY OF ASIA 7TH EDITION PDF Rhoads Murphey | 9780205168552 | | | | | Editions of A History of Asia by Rhoads Murphey We recommend Burning the Books by Richard Ovenden. Buy now. Delivery included to Germany. Rhoads Murphey author eBook 13 May English. A History of Asia is the only textbook to provide a historical overview of the whole of this region, encompassing India, China, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Engaging and lively, it chronicles the complex political, social, and intellectual histories of the area from prehistory to the present day. Taking a comparative approach throughout, the book offers a balanced history of each major tradition, also dedicating coverage to countries or regions such as Vietnam and Central Asia that are less frequently discussed in depth. This eighth edition has been streamlined and updated to reflect the most recent scholarship on Asian history, bringing the book up to date with recent events and key trends in historical research. Highlights of the book include close-up portraits of significant Asian cities, detailed discussion of environmental factors that have shaped Asian history, quotes from Asian poetry and philosophical writing, and attention to questions of gender and national identity. Highly illustrated with images and maps, each chapter also contains discussion questions, A History of Asia 7th edition source excerpts, and in-depth boxed features. Written clearly throughout, A History of Asia is the perfect introductory textbook for all students of the history, culture, and politics of this fascinating region. Routledge is the world's leading academic publisher in the Humanities and Social Sciences. We publish thousands of books and journals each year, serving scholars, instructors, and professional communities worldwide. -

Thai Studies in the United States1 Ä·ÂÈÖ¡Éòã¹êëãñ°Íàáãô¡Ò

Thai Studies & Thai-ization 19 Thai Studies in the United States1 ä·ÂÈÖ¡ÉÒã¹ÊËÃÑ°ÍàÁÃÔ¡Ò Charles F. Keyes ชารลส เอฟ. คายส Abstract “Thai Studies” in the United States have always been infl uenced – some would even say on occasion been determined – by American policies regarding Thailand and by Thai politics. In this paper I trace the development of Thai studies in the US from the immediate post-World War II period when a few American scholars began to develop Thai studies to the present day. Since the early twenty-fi rst century, fewer and fewer American graduate students have chosen to study Thailand and fewer and fewer Thai are coming to the US to study. Nonetheless, Thai studies in America will not disappear. The impressive Thai collections at libraries at Cornell, Wisconsin, Northern Illinois University, and the University of Washington and smaller collections elsewhere ensure that there will continue to be a signifi cant scholarly legacy for Thai studies in the United States. Future scholars – from Thailand, the US and elsewhere will be able to fi nd in these collections signifi cant materials for future research. Keywords: Thai studies, the United States, Thailand 20 วารสารสังคมศาสตร ปที่ 29 ฉบับที่ 1/2560 (มกราคม-มิถุนายน) บทคัดยอ ตลอดระยะเวลาทผี่ านมา “ไทยศกษาึ ” ในสหรฐอเมรั กามิ กจะไดั ร บอั ทธิ พลิ จากนโยบายของอเมริกาที่มีตอประเทศไทย กับทั้งการเมืองของประเทศไทย ในบทความนี้ ผูเขียนยอนใหเห็นถึงพัฒนาการของไทยศึกษาในสหรัฐอเมริกา จากยุคหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่สองที่มีนักวิชาการชาวอเมริกันเพียงไมกี่คนไดเริ่ม พัฒนางานไทยศึกษา มาจนถึงปจจุบัน