Date: February 2005 TERMINAL EVALUATION REPORT PROJECT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourth Review Idp 2016-2017

; FINAL APPROVED FOURTHFF REVIEWED IDP IDP DOCUMENT 2016-2017 i | Page: Final Approved Fourth Reviewed IDP 2016 - 2017 Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor .......................................................................................................... v Foreword by the Municipal Manager ................................................................................ vii Executive summary ................................................................................................................ ix Acronyms ................................................................................................................................. xii Chapter 1.................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………………….1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Guiding Principles……………………………………………………………………………...1 1.2.1 National Government’s outcomes based on delivery .................................... 2 1.2.2 National Development Plan ................................................................................ 2 1.2.3 CoGTA- National KPA's for municipalities .......................................................... 2 1.2.4. New Growth Path………………………………………………………………………..2 1.2.5 Northern Cape Provincial Spatial Development framework(2012)…………….3 1.2.6 Northern Cape Growth and Development Strategy……………………………...3 -

14 Northern Cape Province

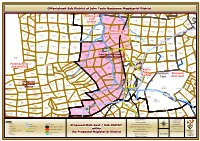

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

36740 16-8 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA August Vol. 578 Pretoria, 16 2013 Augustus No. 36740 PART 1 OF 2 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 303563—A 36740—1 2 No. 36740 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 AUGUST 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke -

NC Sub Oct2016 ZFM-Postmasburg.Pdf

# # !C # ### # ^ #!.C# # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # ## # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C # # # # # ## # #!C# # # # # # #!C # # ^ ## # !C# # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # # ^ !C # # # ^# # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # !C # # # !C# ## # !C# # ## # # # # #!C # # # #!C##^ # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# ## ## # ## # # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## #!C ## # ## # # !C### # # # # # # # # # # # # !C## # # ## #!C # # # ##!C# # # # ##^# # # # # ## ###!C# # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # ## # # ## !C# #^ # #!C # # !C# # # # # # # ## # # # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # ### # # ## ## # # # # ### ## ## # # # # !C# # !C # # # #!C # # # #!C# ### # #!C## # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # ## ## # # ## # # ## # # # # # # ## ### ## # ##!C # ## # # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ ## # #### ## # # # # # # #!C# # ## # ## #!C## # #!C# ## # # !C# # # ##!C#### # # ## # # # # # !C# # # # ## ## # # # # # ## # ## # # # ## ## ##!C### # # # # # !C # !C## #!C # !C # #!.##!C# # # # ## # ## ## # # ### #!C# # # # # # # ## ###### # # ## # # # # # # ## ## #^# ## # # # ^ !C## # # !C# ## # # ### # # ## # ## # # ##!C### ##!C# # !C# ## # ^ # # # !C #### # # !C## ^!C#!C## # # # !C # #!C## #### ## ## #!C # ## # # ## # # # ## ## ## !C# # # # ## ## #!C # # # # !C # #!C^# ### ## ### ## # # # # # !C# !.### # #!C# #### ## # # # # ## # ## #!C# # # #### # #!C### # # # # ## # # ### # # # # # ## # # ^ # # !C ## # # # # !C# # # ## #^ # # ^ # ## #!C# # # ^ # !C# # #!C ## # ## # # # # # # # ### #!C# # #!C # # # #!C # # # # #!C #!C### # # # # !C# # # # ## # # # # # # # # -

Report Groblershoop Sanddraai 391 Royal Haskon 2014

25 NOVEMBER 2014 FIRST PHASE ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE INVESTIGATION OF THE PROPOSED PV ENERGY DEVELOPMENTS AT THE FARM SANDDRAAI 391 NEAR GROBLERSHOOP, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Solafrica Photovoltaic Energy from Rivonia Road, Sandhurst, is planning the construction of a combined Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) and Photo Voltaic (PV) project on the farm Sanddraai 391, near Groblershoop in the Northern Cape. The farm covers about 4600ha. The land can be divided into two parts: a low lying area near the Orange River on bare layers of calcrete and further away, sterile red sand dunes covered by stands of Bushman Grass ( Cipa sp .) with indigenous trees and shrubs. Several heritage impact assessments around Groblershoop and Olifantshoek and along the Sishen-Saldanha railway line produced archaeological and historical material. In the case of Sanddraai 391, archaeological remains in the form of flaked cores and core flakes were found previously and in the present case along the river. Scatters of worked stone artefacts were found in association with calcrete outcrops. No dense concentrations occurred. Along the Orange River, cultural and historical remnants go along with human occupation, represented by a farm yard consisting of a residential house and a well built kraal with a solar installation and water supply equipment. No graves were found. Mitigation measures will be necessary in case graves or other human skeletal or unidentified heritage resources are found during the construction phase. Although the red sand dunes seem to be sterile, it is possible that the dune crests and streets between dunes could have been the activity and dwelling places during the Later Stone Age. -

B&Km Completes Challenging Iron Ore Rail Siding Contract

Press release from Jan de Beer, cell 082 456 3677: B&KM COMPLETES CHALLENGING IRON ORE RAIL SIDING CONTRACT Local civil engineering contractors, Botes & Kennedy Manyano (B&KM), has completed a challenging R12,7m contract for the concrete structures required for a new iron ore export railway siding for the new Khumani Iron Ore Mine in the Northern Cape. Morné van der Merwe, director of B&KM, says the project involved the construction of a rail-over-road bridge with post-tensioned, precast beams as well as all the other concrete structures including in-situ culverts, precast pipe and portal culverts on the siding. Work started on the Assmang contract in July last year and was completed in May this year. Van der Merwe said the bridge is one of few in South Africa with the capacity to carry the individual loads of 120t iron ore wagons, or full train loads of 41 000t, over the R325 road to Dingleton onto the Sishen-Saldanha railway line. “These exceptionally heavy loads, and the long 20m span of the bridge, called for a 1m wide bottom flange for the beams as well as more reinforcing and cable sleeves for post-tensioning. B&KM had to get the required 50MPa concrete fully compacted to all corners of the beams. This was achieved through a special concrete mix designed by Chryso SA, and a special Chryso admixture for self-compacting concrete.” Hennie van Heerden, Chryso SA Technical Services Manager, says the project called for self-compacting concrete because of the intricate shape of the structure and highly congested reinforcement at very narrow spacing. -

Integrated Development Plan Gamagara Local Municipality

Year: 2017-2022 Integrated Development Plan Gamagara Local Municipality i | Page: DRAFT IDP 2017 - 2022 Table of Contents Foreword by the Mayor ......................................................................................................... v Foreword by the Municipal Manager ................................................................................ vii Executive summary ................................................................................................................ ix Acronyms .................................................................................................................................xii Chapter 1.................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Legislative Framework…….…………………………………………………………………….1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Legislative Frameworks..……………………………………………………………………...1 1.2.1 Constitution of Republic Of South Africa (1996) ........................................................ 1 1.2.2 White Paper on Local Government (1998) ................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Municipal Systems Act ................................................................................................... 2 1.2.4. National Development Plan..……………………………………………………………..2 1.2.5 National Outcomes…………………………………………………………...…………….3 1.2.6 Provincial Spatial Development plan…………………………………………………...3 -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape Permit Number Primary Name Address 202103969 Coleberg Correctional Petrusville road, services Colesberg Centre, Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103950 Upington Clinic Schroder Street 52 Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103841 Assmang Blackrock Sering Avenue Mine OHC J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103831 Schmidtsdrift Satellite Sector 4 Clinic Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103744 Assmang Khumani Mine 1 Dingleton Road, Wellness Centre Dingleton J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103270 Prieska Clinic Bloekom Street, Prieska, 8940 Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103040 Kuyasa Clinic Tutuse Street Kuyasa Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103587 Petrusville Clinic Thembinkosi street, 1928 New Extention Petrusville Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103541 Keimoes CHC Hoofstraat 459 ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103525 Griekwastad 1 Moffat Street (Helpmekaar) CHC Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103457 Medirite Pharmacy - Erf 346 Cnr Livingstone Kuruman Road & Seadin Way J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103444 Progress Clinic Bosliefie Street,Progress Progress,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103443 Sarah Strauss Clinic Leeukop Str. Rosedale,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103442 Louisvaleweg Clinic Louisvale Weg Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103441 Lehlohonolo Adams Monyatistr 779 Bongani Clinic Douglas Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103430 Florianville (Floors) Stokroos Street, Clinic Squarehill Park, Kimberley -

Integrated Development Plan Draft John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality

2021-22 Integrated Development Plan Draft John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality INDEX 1. Section A: Executive Summary 1.1. Process to compile the 2021-2022 IDP Page 4 1.1.1. Consultation Page 4 1.1.2. Technical Process of compiling the IDP Page 6 1.2. Development Priorities Page 7 1.3. Achievements & Challenges Page 8 1.4. Development Priorities (Strategic Objectives) Page 10 2. Section B: Situational Analysis 2.1. The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Area Page 22 2.1.1. Population and Demographics Page 23 2.2. Spatial Analysis Page 26 2.2.1. Settlement Density Page 26 2.2.2. Hierarchy of Settlements Page 26 2.2.3. Land Use Composition Page 27 2.2.4. Land Claims Page 27 2.3. Basic Services Deliveries Page 28 2.3.1. Water and Sanitation Page 28 2.3.2. Refuse Removal Page 30 2.3.3. Energy and Electricity Page 30 2.3.4. Roads, Storm water and Transport Page 32 2.4. Social Analysis/Services Page 2.4.1. Housing Page 34 2.4.2. Education Page 36 2.4.3. Health And Social Development Page 39 2.4.4. Safety and Security Page 39 2.4.5. Employment Profile Page 40 2.5. Bio-Physical Environment Page 41 2.5.1. Topography and Hydrology Page 41 2.5.2. Climate Page 42 2.5.3. Climate Change Page 43 2.5.4. Fauna and Flora Page 43 2.5.5. Vegetation Page 44 2.5.6. Biodiversity, Environmental Sensitivity and Protected Page 46 Areas 2.5.7. -

NC Sub Oct2016 JTG-Olifantshoek

# # !C # # ### !C^# !.!C# # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # # ^ # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # # # # # # !C# # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # ##^ # !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C ## # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # !C #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ### !C # # # # !C !C# # ## # # # ## !C !C #!. # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C# # # # ## # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ### #^ # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # !C ## !C## # # # # ## # !C # ## !C# ## # # ## # !C # # ^ # !C ## # # # !C# ^# # # !C # # # !C ## # # #!C ## # # # # # # # # # ## # !C## ## # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # !. # # #!C # # # # # !C # # ## -

Tariff Increase Consultation 2020/2021

“Excellence in water services provision” TARIFF INCREASE CONSULTATION 2020/2021 PRESENTATION BY SEDIBENG WATER OCTOBER / NOVEMBER 2019 (nat.) (056) 515 0200 (nat.) (056) 515 0369 (intl.) (+ 2756) 515 0200 (intl.) (+ 2756) 515 0369 1 Table of Contents 1.Introduction 2.Area of Supply and Operation 3.Legislative requirements 4.Assumptions and cost drivers 5.Free State Region Tariff Increase Proposal 6.North West Region Tariff Increase Proposal 7.Namakwa Region Tariff Increase Proposal 8.Pella Region Tariff Increase Proposal 9.Vaal Gamagara Region Tariff Increase Proposal 10.Way forward 2 1. Introduction • As part of our Risk Management Strategies, our view is that tariff increases should be responsible, prudent and market-related in order to ensure sufficient cash and income generation for long-term sustainability. • To maintain financial credibility, our financial strategies are geared to deliver positive cash positions in order to fund capital expansions internally. • We continuously review our internal business processes to ensure that the internal value chain create customer and stakeholder satisfaction. • Recent growth has necessitated a review of the organisational structure and strategy. • Priorities aimed at creating a climate that supports organisational change, innovation and skills development. 3 2. Area of Supply and Operations • Sedibeng Water operates in the following areas: Free State Province: Matjhabeng Local Municipality Nala Local Municipality FREE STATE North West Province: Maquassi-Hills Local Municipality Dr Ruth Mompati District Municipality Ditsobotla Local Municipality Mahikeng Local Municipality Ngaka Modiri Molema District Municipality NORTH WEST Northern Cape Province: Phokwane Local Municipality Ga-Segonyane Local Municipality Tsantsabane Local Municipality Gamagara Local Municipality VAAL GAMAGARA Dikgatlong Local Municipality Joe Morolong Local Municipality Nama Khoi Local Municipality NAMAKWA Khâi-Ma Local Municipality PELLA 4 2. -

Report Olifantshoek Inglesby 580 Prospecting Re a Kgona

10 MAY 2014 FIRST PHASE ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE INVESTIGATION OF THE PROPOSED MINE PROSPECTING AT THE REMAINING EXTENT OF THE FARM INGLESBY 580 NEAR OLIFANTSHOEK, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Re A Kgona General Services from Kimberley is planning a prospecting and mining application on the Remainder of the farm Inglesby 580 near Olifantshoek in the Northern Cape. The land covers about 2600ha and can be divided into two parts, a low lying area made up of sterile coarse red sandy soil covered by indigenous trees and shrubs, and a mountainous part with steep slopes densely covered by a thick stand of almost impenetrable thorn bush and undergrowth. A number of heritage impact assessments around Olifantshoek produced archaeological and historical material. In the case of Inglesby 580, no archaeological remains were found. Cultural and historical remnants mainly revolve around the European occupation of the area in the Kloof. Several grave sites and old farm yards occur here. Road building for prospecting and mining activities will have a serious impact on these heritage remains and I recommend that the developers should avoid the lower part of the land and the Kloof during the planning, prospecting and mining phases of the project. I recommend that the access road should be from the top of the ridge. Mitigation measures will be required to protect the grave yards and cultural remains. A special effort should be made to find and protect the rock paintings and in case of the discovery of any archaeological or heritage material, the work should stop and a qualified archaeologist should be informed.