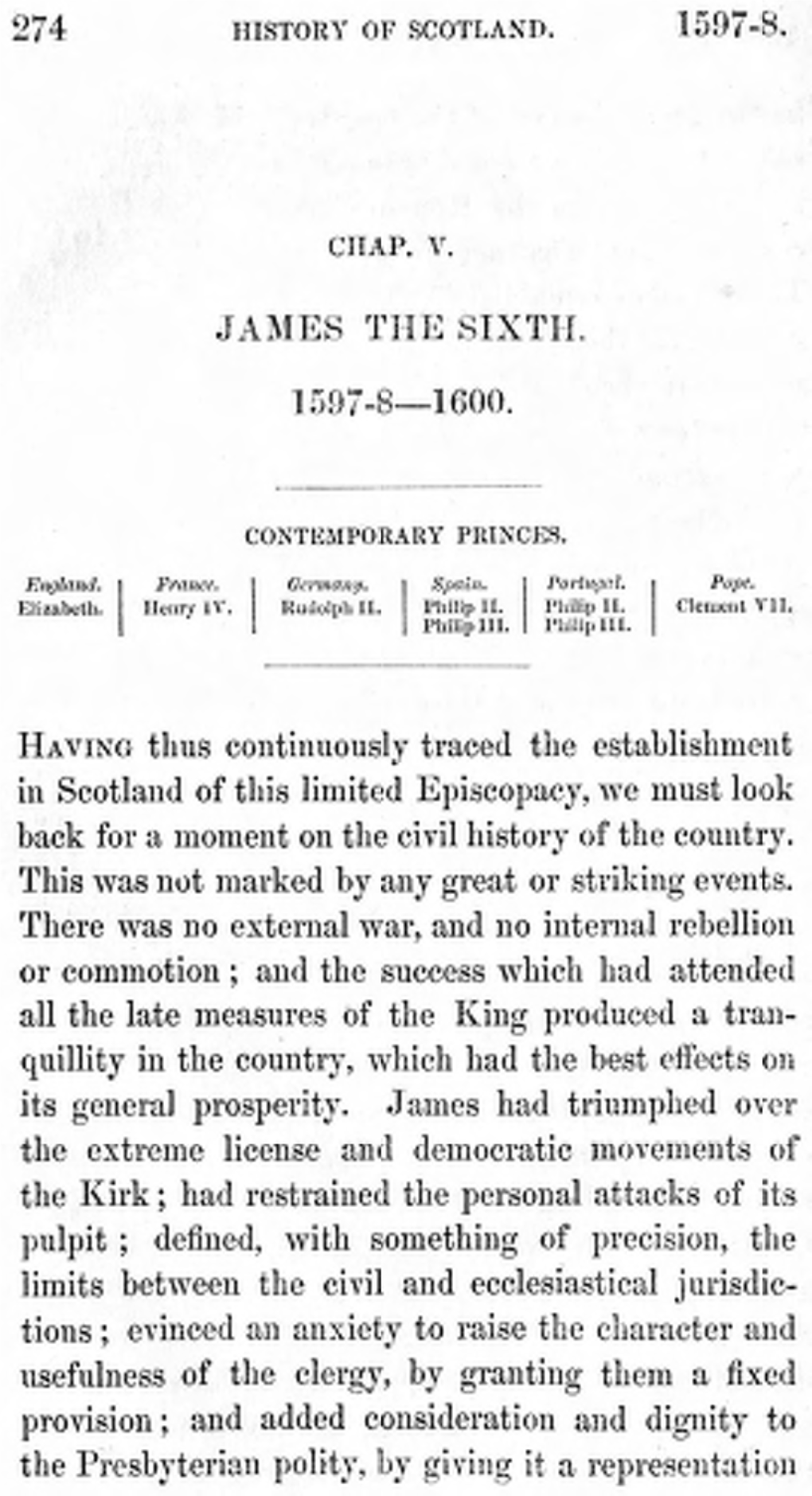

JAMES the SIXTH. 1597-8-1600. HAVING Thus Continuously Traced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF EPUB} the Correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske Esquire

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske Esquire the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scotland by Robert Bowes Jun 09, 2008 · The correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, esquire, the ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the court of Scotland Item PreviewPages: 636Images of The Correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske Esquire T… bing.com/imagesSee allSee all imagesThe Correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, Esquire, the ...https://www.amazon.com/Correspondence-Esquire...The Correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, Esquire, the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scotland [Stevenson, Joseph, Bowes, Robert] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. The Correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, Esquire, the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scotland The correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske, esquire, the ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the court of Scotland by Bowes, Robert, 1535?- 1597 ; Stevenson, Joseph, 1806-1895 The Correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, Esquire, the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scotland Volume 14 of Publications of the Surtees Society: … Amazon.com: The Correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske, Esquire, the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scorland (9780543968517): Bowes, Robert: BooksAuthor: Bowes, Robert, Joseph Stevenson, Robert BowesPublish Year: 2004The correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske, esquire, the ...https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001679795The correspondence of Robert Bowes of Aske, esquire, the ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the court of Scotland. The Correspondence of Robert Bowes, of Aske, Esquire, the Ambassador of Queen Elizabeth in the Court of Scotland Volume 14 of Publications of the Surtees Society Volume 14 of Publications, Durham Surtees Society (England) Author: Robert Bowes: Editor: Joseph Stevenson: Publisher: J. -

107394589.23.Pdf

Scs s-r<?s/ &.c £be Scottish tlert Society SATIRICAL POEMS OF THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION SATIRICAL POEMS OF THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION EDITED BY JAMES CRANSTOUN, LL.D. VOL. II. ('library''. ) Printcti fat tljt Sacietg Iig WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCXCIII V PREFATORY NOTE TO VOL. II. The present volume is for the most part occupied with Notes and Glossary. Two poems by Thomas Churchyard — “ The Siege of Edenbrough Castell ” and “ Mvrtons Tragedie ”—have been included, as possessing considerable interest of themselves, and as illustrating two important poems in the collection. A complete Index of Proper Names has also been given. By some people, I am aware, the Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation that have come down to us through black- letter broadsheets are considered as of little consequence, and at best only “sorry satire.” But researches in the collections of historical manuscripts preserved in the State-Paper Office and the British Museum have shown that, however deficient these ballads may be in the element of poetry, they are eminently trustworthy, and thus have an unmistakable value, as contemporary records. A good deal of pains has accordingly been taken, by reference to accredited authorities, to explain unfamiliar allusions and clear up obscure points in the poems. It is therefore hoped that not many difficulties remain to perplex the reader. A few, however, have defied solution. To these, as they occurred, I have called attention in the notes, with a view to their being taken up by others who, with greater knowledge of the subject or ampler facilities for research than I possess, may be able to elucidate them. -

Irish and Scots

Irish and Scots. p.1-3: Irish in England. p.3: Scottish Regents and Rulers. p.4: Mary Queen of Scots. p.9: King James VI. p.11: Scots in England. p.14: Ambassadors to Scotland. p.18-23: Ambassadors from Scotland. Irish in England. Including some English officials visiting from Ireland. See ‘Prominent Elizabethans’ for Lord Deputies, Lord Lientenants, Earls of Desmond, Kildare, Ormond, Thomond, Tyrone, Lord Bourke. 1559 Bishop of Leighlin: June 23,24: at court. 1561 Shane O’Neill, leader of rebels: Aug 20: to be drawn to come to England. 1562 Shane O’Neill: New Year: arrived, escorted by Earl of Kildare; Jan 6: at court to make submission; Jan 7: described; received £1000; Feb 14: ran at the ring; March 14: asks Queen to choose him a wife; April 2: Queen’s gift of apparel; April 30: to give three pledges or hostages; May 5: Proclamation in his favour; May 26: returned to Ireland; Nov 15: insulted by the gift of apparel; has taken up arms. 1562 end: Christopher Nugent, 3rd Lord Delvin: Irish Primer for the Queen. 1563 Sir Thomas Cusack, former Lord Chancellor of Ireland: Oct 15. 1564 Sir Thomas Wroth: Dec 6: recalled by Queen. 1565 Donald McCarty More: Feb 8: summoned to England; June 24: created Earl of Clancare, and son Teig made Baron Valentia. 1565 Owen O’Sullivan: Feb 8: summoned to England: June 24: knighted. 1565 Dean of Armagh: Aug 23: sent by Shane O’Neill to the Queen. 1567 Francis Agard: July 1: at court with news of Shane O’Neill’s death. -

Scotland to England 1

SCOTLAND TO ENGLAND Hiram Morgan 1 TO ENGLAND (1474)-1 Bp of Aberdeen, Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, James Schaw of Sauchy; Lyon herald. Commission 15 June 1474. July in London. Ambassadors Hiram£20 prepayment to Lyon. Embassy suggested by parliament for treaty confirmation, redress & possible marriage alliance between infant prince of Scotland and Cecilia, daughter of Ed IV. TA 1 lv-vi. Morgan 2 TO ENGLAND (1474)-2 Lyon herald Leaves after 3 Nov, signs document in London on 3 Dec 3 Nov 1474 J3 signs articles of peace & Lyon proceeds to London 'for the interchanging of the truces'. 3 Dec LH signs indenture re remission of Cecilia's dowry HiramTA 1 p.lix. Morgan 3 TO ENGLAND (1488) Abp of St Andrews, bps of Aberdeen & Glasgow Sent after the death of J3 & coronation of J4. Ambassadors HiramObtained renewal of truce arranged in 1486 TA 1 pp.lxxiv-v; (Also derived from Rymer’s Foedera, XII, 343,345. Morgan 4 TO ENGLAND (1501-2) Abp. of Glasgow, Patrick. E. of Bothwell, Adw. Forman, bp. elect of Moray; Sir John Home of Aytoun; Lyon Herald; Dunbar? Commissioned 8 Oct 1501, left soon after Ambassadors £28 to Home; £18 & £8 8s to Lyon. HiramMarriage contract of J4 & Margaret signed 29 1 1502. En & Sc commissioners also conclude a perpetual peace & an extradition treaty. TA 2 pp.liv-vi, 122, 132. Morgan 5 TO ENGLAND (1502) Lyon herald Sent 23 Dec 1502 £28 prepayment Post haste to EN with the truces 'when Sir Thomas Darcy would not interchange' TA 2 p.352 Hiram Morgan 6 TO ENGLAND (1507) R. -

Scotland in Renaissance Diplomacy, 1488-1603

TO SCOTLAND Hiram Morgan 1 FROM DENMARK (1473/4) An esquire of the king of Denmark Envoy Lodged at Snowdon herald's house; K of SC entrusted him with buying Hirammunitions in DK when departing. TA 1 pp. lv, 68, 69. Morgan 2 FROM DENMARK (1495) Chancellor of DK Ambassador Probably return mission to treat on matters propounded by Lord Ogilvy in DK. HiramTA 1 pp.cxvii, 240; (as derived from Exchequer Rolls no. 307). Morgan 3 FROM DENMARK (1496) Herald of Denmark Leaving SC 20 March 1496. HiramTA 1 p.325. Morgan 4 FROM DENMARK (1497) Chancellor of DK Ambassador HiramTA 1 pp.cxviii, 240, (as derived from Exchequer Rolls. no.310). Morgan 5 FROM DENMARK (1503) Thomas Lummysdene, herald of Denmark. ???? HiramTA 2 p.373 Morgan 6 FROM DENMARK (1505) Thomas Lummysden in SC in Feb herald HiramAudience 3 Feb Brought 'Christofer' - Prince Christian? - who is now to be one of the royal pages. Zeeland reports on the state of the war & negotiations. LJ4 3-4. Morgan 7 FROM DENMARK (1506)-1 Thomas Lummysden, Zeeland herald of DK. Delivered letters of 5 March & 4 May on July 10 letter delivery. Zeeland not permitted to continue to H7 but sent back to DK with HiramMountjoy k of Arms. LJ4 27-9 Morgan 8 FROM DENMARK (1506)-2 Thomas Lummysden, Zeeland herald of Denmark. Given instructions in Sept. Left SC on or after 15 Oct. Envoy?? HiramFrench Marriage of King John's son, and military help from James against Lubeck-Swedish alliance next summer. Zeeland continues to FR with SC LJ4, 33; TA 3 lxxiv, v, 350. -

Siobhan Talbott Phd Thesis

AN ALLIANCE ENDED? : FRANCO-SCOTTISH COMMERCIAL RELATIONS, 1560- 1713 Siobhan Talbott A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1999 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons License AN ALLIANCE ENDED?: Franco-Scottish Commercial Relations, 1560-1713 Siobhan Talbott Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of St Andrews August 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the commercial links between Scotland and France in the long seventeenth century, with a focus on the Scottish mercantile presence in France’s Atlantic ports. This study questions long-held assumptions regarding this relationship, asserting that the ‘Auld Alliance’ continued throughout the period, despite the widely held belief that it ended in 1560. Such assumptions have led scholars largely to ignore the continuing commercial relationship between Scotland and France in the long seventeenth century, focusing instead on the ‘golden age’ of the Auld Alliance or the British relationship with France in the eighteenth century. Such assumptions have been fostered by the methodological approaches used in the study of economic history to date. While I acknowledge the relevance of traditional quantitative approaches to economic history, such as those pioneered by T. C. Smout and which continue to be followed by historians such as Philipp Rössner, I follow alternative methods that have been recently employed by scholars such as Henriette de Bruyn Kops, Sheryllynne Haggerty, Xabier Lamikiz, Allan Macinnes and Steve Murdoch. -

University of York December 1991

THE BOWES OF STREATLAM. COUNTY DURHAM: A STUDY OF THE POLITICS AND RELIGION OF A SIXTEENTH CENTURY NORTHERNGENTRY FAMILY. CHRISTINE MARY NEWMAN SUBMITTED FOR THE QUALIFICATION OF DOCTOROF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITYOF YORK DEPARTMENTOF HISTORY DECEMBER1991 CONTENTS Abbreviations. p. 5 Introduction. p. 7 1. The Bowes of Streatlam in the Later Middle Ages: p. 22 the Foundation of Family, Inheritance and Tradition. 2. Service, Rebellion and Achievement; p. 71 Robert Bowes and the Pilgrimage of Grace. 3. The Rewards of Loyalty: p. 126 Robert Bowes and the Late Henrician Regime. 4. The Bowes of Streatlam and the Era of Reform: p. 171 1547-1553. 5. Sir George Bowes and the Defence of p. 226 the North: 1558-1569. 6. The House of Bowes and the end of an Era. p. 260 Conclusion: The Bowes of Streatlam and the p. 307 Tudor Regime: An Overview. Bibliography. p. 344 -2- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe an immense debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Professor M. C. Cross of the Department of History, University of York, whose inspirational guidance and encouragement has made the completion of this thesis possible. I would like, also, to thank Dr. A. J. Pollard, Reader in History at Teesside Polytechnic, who first introduced me to the Bowes family and who has provided me with considerable support and advice throughout the course of my study. I am grateful, too, for the unfailing support and encouragement given to me by members of Professor Cross's postgraduate seminar group, particularly Dr. D. Lamburn, Dr. D. Scott and Mr. J. Holden. Special thanks are due to the Earl of Strathmore who kindly granted me access to the Bowes letterbooks, held amongst the muniments at Glamis Castle. -

King James VI of Scotland's Foreign Relations with Europe (C.1584-1603)

DIPLOMACY & DECEPTION: KING JAMES VI OF SCOTLAND'S FOREIGN RELATIONS WITH EUROPE (C. 1584-1603) Cynthia Ann Fry A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/5902 This item is protected by original copyright DIPLOMACY & DECEPTION: King James VI of Scotland’s Foreign Relations with Europe (c. 1584-1603) Cynthia Ann Fry This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews October 2014 ABSTRACT This thesis is the first attempt to provide an assessment of Scottish-Jacobean foreign relations within a European context in the years before 1603. Moreover, it represents the only cohesive study of the events that formed the foundation of the diplomatic policies and practices of the first ruler of the Three Kingdoms. Whilst extensive research has been conducted on the British and English aspects of James VI & I’s diplomatic activities, very little work has been done on James’s foreign policies prior to his accession to the English throne. James VI ruled Scotland for almost twenty years before he took on the additional role of King of England and Ireland. It was in his homeland that James developed and refined his diplomatic skills, and built the relationships with foreign powers that would continue throughout his life. James’s pre-1603 relationships with Denmark-Norway, France, Spain, the Papacy, the German and Italian states, the Spanish Netherlands and the United Provinces all influenced his later ‘British’ policies, and it is only through a study such as this that their effects can be fully understood. -

The English Border Town of Berwick-Upon-Tweed, 1558-1625

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 From A “strong Town Of War” To The “very Heart Of The Country”: The English Border Town Of Berwick-Upon-Tweed, 1558-1625 Janine Maria Van Vliet University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Van Vliet, Janine Maria, "From A “strong Town Of War” To The “very Heart Of The Country”: The English Border Town Of Berwick-Upon-Tweed, 1558-1625" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3078. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3078 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3078 For more information, please contact [email protected]. From A “strong Town Of War” To The “very Heart Of The Country”: The English Border Town Of Berwick-Upon-Tweed, 1558-1625 Abstract The English border town of Berwick-upon-Tweed provides the perfect case study to analyze early modern state building in the frontiers. Berwick experienced two seismic shifts of identity, instituted by two successive monarchs: Elizabeth I (1558-1603) and James I (1603-1625). Both sought to expand state power in the borders, albeit in different ways. Elizabeth needed to secure her borders, and so built up Berwick’s military might with expensive new fortifications and an enlarged garrison of soldiers, headed by a governor who administered the civilian population as well. This arrangement resulted in continual clashes with Berwick’s traditional governing guild. Then, in 1603, Berwick’s world was turned upside-down when James VI, king of Scotland, ascended the English throne. -

The Correspondence of Elizabeth I and James VI in the Context of Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1572-1603

The Correspondence of Elizabeth I and James VI in the context of Anglo-Scottish Relations, 1572-1603 Elizabeth Tunstall BA Hons (University of New England, Australia) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of History School of Humanities, Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide, Australia September 2015 Abstract From 1572 until 1603 Queen Elizabeth I of England maintained a significant correspondence with King James VI of Scotland. This correspondence has recently begun to receive some scholarly attention but generally it sits separated from its context in historical analysis. This thesis seeks to analyse the lengthy correspondence in order to understand its role in diplomacy and to reintegrate it into its broader Anglo-Scottish diplomatic context. In doing so it explores the idea of the existence of a multilayered approach to diplomatic relations during the Elizabethan period, which enabled Elizabeth to manage the difficulties that arose in the Anglo-Scottish relationship. The thesis discusses the role of the correspondence through four main concerns that occurred from 1585 until Elizabeth’s death in 1603. It commences by examining the negotiations for the Treaty of Berwick that occurred in 1585-1586, negotiations that took place within the royal correspondence and through the work of ambassadors. Shortly after the treaty’s conclusion the discovery of Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, involvement in the Babington plot sparked a diplomatic storm that involved not only the various threads of Anglo-Scottish diplomatic relations but also pressure from France. Diplomatic relations were only restored shortly before the Spanish Armada but were immediately placed under significant strain by the uncovering of the Brig o’ Dee Affair and the Spanish Blanks plot in Scotland. -

The Visitations of Yorkshire in the Years 1563 and 1564, Made By

0279551 i Visitation of gorKsfttre IN THE YEARS 1563 AND 1564, MADE BY WILLIAM FLOWER, ESQUIRE, \\ ~ \. Hottop Itittg of arms. V ^ (X ' DEXIQUE COELESTI SITMUS OMNE3 SEMINE ORIONDI ; OMNIBUS ILLE IDEM PATEB EST." Lucretius. EDITED BY CHARLES BEST NORCLIEFE, MA.., OF LANGTON. CHUR SAINTS LATTER-DAY LONDON 1881. THE p xx li i i c a 1 1 o n s €!je ^arinan ^>®tiztp. ESTABLISHED A.D. MDCCCLXIX. -.. ;.T>'./ Volume X&E FOR THE YEAR MD.CCC.LXXXI. LONDON: SD HUGHES, PRINTERS, preface. The Harleian Society has turned its attention from London to York, and with the publication of this Volume the list of Heraldic Visitations of Yorkshire is complete. It may be useful to place on record the dates of publication of the other four. That made in 1530 by Thomas Tonge, Norroy, was published by the Surtees Society in 1863, with critical notes such as few persons except its Editor, Mr. W. H. D. Longstaffe, could have furnished. Sir William Dugdale's Visitation of 1664 and 1665 was published by the same Society in 1859, being transcribed from Miss Currer's Manuscript by the late Mr. Robert Davies, F.S.A., sometime Town Clerk of York. Nearly all the proof-sheets were read, and the heraldic descriptions revised, by the Editor of this Work, who was glad to be associated, in however humble a capacity, with the first Visitation of Yorkshire that appeared in print. His share in correcting and revising those of Glover and St. George, made in the years 1584-5 and 1612, and published in 1875 by the commendable enterprise of Mr. -

Durham E-Theses

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Durham e-Theses Durham E-Theses Lead production on the northeast periphery: A study of the Bowes family estate, c.1550-1771 BROWN, JOHN,WILLIAM How to cite: BROWN, JOHN,WILLIAM (2010) Lead production on the northeast periphery: A study of the Bowes family estate, c.1550-1771 , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/558/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Lead production on the northeast periphery: a study of the Bowes family estate, c.1550-1771. John W. Brown Abstract This is a study of a family estate‟s relationship with a high value mineral product. It aims to fill a knowledge gap in the extractive industry‟s history in the Northeast by examining the lead production process on Bowes‟ lands.