Cefnllys Castle Radnorshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trilingualism and National Identity in England, from the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2015 Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century Christopher Anderson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christopher, "Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century" (2015). WWU Graduate School Collection. 449. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/449 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three Languages, One Nation Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century By Christopher Anderson Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School Advisory Committee Chair, Dr. Peter Diehl Dr. Amanda Eurich Dr. Sean Murphy Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

14 High Street, Builth Wells 01982 553004 [email protected]

14 High Street, Builth Wells 01982 553004 [email protected] www.builthcs.co.uk Builth Wells Community Services provided: Support was established in Community Car scheme 1995 and is a registered charity and Company Limited Prescription Delivery by Guarantee. The aims of Befriending Community Support are to Monthly Outings provide services, through our team of 98 Volunteers, which Lunch Club help local people to live “Drop in” information & healthy independent lives signposting within their community and Volunteer Bureau working to be a focal point for with volunteering and general information. Powys Volunteer Centre to promote Volunteering We are demand responsive. All services are accessed by In 2013 we became a Company Limited by requests from individuals, Guarantee , retaining our family members or support charitable status agencies, we can add to statutory service provision; offering the extras that are We also have our own important in people’s lives. Charity Shop at 39 High Street, Builth Wells The office is open 9.30a.m – 1p.m Monday—Friday 2 Organisations 4 Churches 12 Community Councils 14 Health & Social Care 17 Schools 20 Leisure & Social Groups 22 Community Halls 28 Other Contacts 30 Powys Councillors 34 Index 36 3 Action on Hearing Loss Cymru Address: Ground Floor, Anchor Court North, Keen Road, Cardiff, CF24 5JW Tel: 02920 333034 [Textphone: 02920 333036] Email: [email protected] Website: www.actiononhearingloss.org.uk Age Cymru Powys Address: Marlow, South Crescent, Llandrindod, LD1 5DH Tel: 01597 825908 Email: -

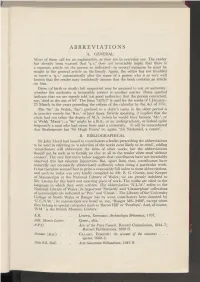

ABBREVIATIONS Use. the Reader That

ABBREVIATIONS A. GENERAL Most of these call for no explanation, as they are in everyday use. The reader has already been warned that 'q.v.' does not invariably imply that there is a separate article on the person so indicated—in several instances he must be sought in the general article on his family. Again, the editor has not troubled to insert a 'q.v.' automatically after the name of a person who is so very well known that the reader may confidently assume that the book contains an article on him. Dates (of birth or death) left unqueried may be assumed to rest on authority: whether the authority is invariably correct is another matter. Dates queried indicate that we are merely told (on good authority) that the person concerned, say, 'died at the age of 64'. The form '1676/7' is used for the weeks of 1 January- 25 March in the years preceding the reform of the calendar by the Act of 1751. The 'Sir' (in Welsh, 'Syr') prefixed to a cleric's name in the older period is in practice merely the 'Rev.' of later times. Strictly speaking, it implied that the cleric had not taken the degree of M.A. (when he would have become 'Mr.', or in Welsh 'Mastr'); a 'Sir' might be a B.A., or an undergraduate, or indeed quite frequently a man who had never been near a university. It will be remembered that Shakespeare has 'Sir Hugh Evans' or, again, 'Sir Nathaniel, a curate'. B. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL Sir John Lloyd had issued to contributors a leaflet prescribing the abbreviations to be used in referring to 'a selection of the works most likely to be cited', adding 'contributors will abbreviate the titles of other works, but the abbreviations should not be such as to furnish no clue at all to the reader when read without context'. -

Cymmrodorion Vol 25.Indd

8 THE FAMILY OF L’ESTRANGE AND THE CONQUEST OF WALES1 The Rt Hon The Lord Crickhowell PC Abstract The L’Estrange family were important Marcher lords of Wales from the twelfth century to the Acts of Union in the sixteenth century. Originating in Brittany, the family made their home on the Welsh borders and were key landowners in Shropshire where they owned a number of castles including Knockin. This lecture looks at the service of several generations of the family to the English Crown in the thirteenth century, leading up to the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1282. With its practice of intermarriage with noble Welsh families, the dynasty of L’Estrange exemplifies the hybrid nature of Marcher society in the Middle Ages. Two points by way of introduction: the first to explain that what follows is taken from my book, The Rivers Join.2 This was a family history written for the family. It describes how two rivers joined when Ann and I married. Among the earliest tributaries traced are those of my Prichard and Thomas ancestors in Wales at about the time of the Norman Conquest; and on my wife’s side the river representing the L’Estranges, rising in Brittany, flowing first through Norfolk and then roaring through the Marches to Wales with destructive force. My second point is to make clear that I will not repeat all the acknowledgements made in the book, except to say that I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the late Winston Guthrie Jones QC, the author of the paper which provided much of the material for this lecture. -

HAY-ON-WYE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Review May 2016

HAY-ON-WYE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Review May 2016 BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Planning Policy Context 3. Location and Context 4. General Character and Plan Form 5. Landscape Setting 6. Historic Development and Archaeology 7. Spatial Analysis 8. Character Analysis 9. Definition of Special Interest of the Conservation Area 10. The Conservation Area Boundary 11. Summary of Issues 12. Community Involvement 13. Local Guidance and Management Proposals 14. Contact Details 15. Bibliography Review May 2016 1. Introduction Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are „areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance‟ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. Hay-on-Wye is one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. Planning authorities have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Local Development Plan. There is also a duty to review Conservation Areas to establish whether the boundaries need amendment and to identify potential measures for enhancing and protecting the Conservation Area. The purpose of a conservation area appraisal is to define the qualities of the area that make it worthy of conservation area status. A clear, comprehensive appraisal of its character provides a sound basis for development control decisions and for developing initiatives to improve the area. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1991 .................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME SEPTEMBER 1991 TO FEBRUARY 1992 ................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 4 BOOK REVIEW .................................................................................................................... 5 WORKERS EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE ............................................................................................................... 6 ANNUAL GARDEN PARTY .................................................................................................. 6 INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MEETING, 15TH MAY, 1991 ................................................ 7 A FIELD SURVEY IN KIMBOLTON ...................................................................................... 7 FIND OF A QUERNSTONE AT CRASWALL ...................................................................... 10 BOLSTONE PARISH CHURCH .......................................................................................... 11 REDUNDANT CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF HEREFORD ........................................ 13 THE MILLS OF LEDBURY ................................................................................................. -

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook

Princes of Gwynedd Guidebook Discover the legends of the mighty princes of Gwynedd in the awe-inspiring landscape of North Wales PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK Front Cover: Criccieth Castle2 © Princes of Gwynedd 2013 of © Princes © Cadw, Welsh Government (Crown Copyright) This page: Dolwyddelan Castle © Conwy County Borough Council PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 3 Dolwyddelan Castle Inside this book Step into the dramatic, historic landscapes of Wales and discover the story of the princes of Gwynedd, Wales’ most successful medieval dynasty. These remarkable leaders were formidable warriors, shrewd politicians and generous patrons of literature and architecture. Their lives and times, spanning over 900 years, have shaped the country that we know today and left an enduring mark on the modern landscape. This guidebook will show you where to find striking castles, lost palaces and peaceful churches from the age of the princes. www.snowdoniaheritage.info/princes 4 THE PRINCES OF GWYNEDD TOUR © Sarah McCarthy © Sarah Castell y Bere The princes of Gwynedd, at a glance Here are some of our top recommendations: PRINCES OF GWYNEDD GUIDEBOOK 5 Why not start your journey at the ruins of Deganwy Castle? It is poised on the twin rocky hilltops overlooking the mouth of the River Conwy, where the powerful 6th-century ruler of Gwynedd, Maelgwn ‘the Tall’, once held court. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If it’s a photo opportunity you’re after, then Criccieth Castle, a much contested fortress located high on a headland above Tremadog Bay, is a must. For more information, see page 15 © Princes of Gwynedd of © Princes If you prefer a remote, more contemplative landscape, make your way to Cymer Abbey, the Cistercian monastery where monks bred fine horses for Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, known as Llywelyn ‘the Great’. -

The Demo Version

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c. -

Llywelyn the Last

LLYWELYN THE LAST KEY STAGE 3 Medieval Wales was a place of warring kings who often met violent deaths, sometimes at the hands of members of their own family! These struggles were usually over local power and influence. All these rulers thought of themselves as Welsh, but their main concern was usually their own small kingdom (and staying alive long enough to help it flourish). The fortunes of these different Welsh kingdoms had risen and fallen over time, but in the thirteenth century the land of Gwynedd in north-west Wales became particularly powerful under the leadership of Llywelyn Fawr (‘Llywelyn the Great’). A skilled military leader, he defeated many rival Welsh rulers and at his death controlled much of Wales. Gwynedd’s power would reach its height, however, under Llywelyn Fawr’s grandson, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (‘Llywelyn the Last’). Llywelyn ap Gruffudd conquered several Welsh kingdoms, and soon claimed to be ruler over the whole of Wales, calling himself ‘Prince of Wales’. Many Welsh leaders swore loyalty to Llywelyn and recognised his authority, although even now some Welsh lords opposed him. The troubles experienced by a weakened English crown at this time saw Henry III sign the Treaty of Montgomery in 1267 which recognised Llywelyn’s title as Prince of Wales and ensured it would be passed on to his successors. ‘Wales’ now had a leader and a hereditary office he could occupy. Llywelyn had squeezed concessions out of Henry III who was a relatively ineffective English king, but the next king, Edward, was a different prospect. Edward I came to the throne in 1272. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’).