Amending International Olympic Committee Rule 40 for the Modern Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's 3000M Steeplechase

Games of the XXXII Olympiad • Biographical Entry List • Women Women’s 3000m Steeplechase Entrants: 47 Event starts: August 1 Age (Days) Born SB PB 1003 GEGA Luiza ALB 32y 266d 1988 9:29.93 9:19.93 -19 NR Holder of all Albanian records from 800m to Marathon, plus the Steeplechase 5000 pb: 15:36.62 -19 (15:54.24 -21). 800 pb: 2:01.31 -14. 1500 pb: 4:02.63 -15. 3000 pb: 8:52.53i -17, 8:53.78 -16. 10,000 pb: 32:16.25 -21. Half Mar pb: 73:11 -17; Marathon pb: 2:35:34 -20 ht EIC 800 2011/2013; 1 Balkan 1500 2011/1500; 1 Balkan indoor 1500 2012/2013/2014/2016 & 3000 2018/2020; ht ECH 800/1500 2012; 2 WSG 1500 2013; sf WCH 1500 2013 (2015-ht); 6 WIC 1500 2014 (2016/2018-ht); 2 ECH 3000SC 2016 (2018-4); ht OLY 3000SC 2016; 5 EIC 1500 2017; 9 WCH 3000SC 2019. Coach-Taulant Stermasi Marathon (1): 1 Skopje 2020 In 2021: 1 Albanian winter 3000; 1 Albanian Cup 3000SC; 1 Albanian 3000/5000; 11 Doha Diamond 3000SC; 6 ECP 10,000; 1 ETCh 3rd League 3000SC; She was the Albanian flagbearer at the opening ceremony in Tokyo (along with weightlifter Briken Calja) 1025 CASETTA Belén ARG 26y 307d 1994 9:45.79 9:25.99 -17 Full name-Belén Adaluz Casetta South American record holder. 2017 World Championship finalist 5000 pb: 16:23.61 -16. 1500 pb: 4:19.21 -17. 10 World Youth 2011; ht WJC 2012; 1 Ibero-American 2016; ht OLY 2016; 1 South American 2017 (2013-6, 2015-3, 2019-2, 2021-3); 2 South American 5000 2017; 11 WCH 2017 (2019-ht); 3 WSG 2019 (2017-6); 3 Pan-Am Games 2019. -

Olympic Charter

OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 OLYMPIC CHARTER IN FORCE AS FROM 17 JULY 2020 © International Olympic Committee Château de Vidy – C.P. 356 – CH-1007 Lausanne/Switzerland Tel. + 41 21 621 61 11 – Fax + 41 21 621 62 16 www.olympic.org Published by the International Olympic Committee – July 2020 All rights reserved. Printing by DidWeDo S.à.r.l., Lausanne, Switzerland Printed in Switzerland Table of Contents Abbreviations used within the Olympic Movement ...................................................................8 Introduction to the Olympic Charter............................................................................................9 Preamble ......................................................................................................................................10 Fundamental Principles of Olympism .......................................................................................11 Chapter 1 The Olympic Movement ............................................................................................. 15 1 Composition and general organisation of the Olympic Movement . 15 2 Mission and role of the IOC* ............................................................................................ 16 Bye-law to Rule 2 . 18 3 Recognition by the IOC .................................................................................................... 18 4 Olympic Congress* ........................................................................................................... 19 Bye-law to Rule 4 -

A Longitudinal Analysis of the Super Bowl

RESEARCH AND REVIEWS Journal of Sport Management, 2008, 22, 392-409 © 2008 Human Kinetics, Inc. Mega-Special-Event Promotions and Intent To Purchase: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Super Bowl Norm O’Reilly Mark Lyberger Laurentian University Kent State University Larry McCarthy Benoît Séguin Seton Hall University University of Ottawa John Nadeau Nipissing University Mega-special-event properties (sponsees) have the ability to attain significant resources through sponsorship by offering exclusive promotional opportunities that target sizeable consumer markets and attract sponsors. The Super Bowl, one of the most watched television programs in the world, was selected as the mega- special-event for this study as it provides a rare environment where a portion of the television audience tunes in specifically for the purpose of watching new and entertaining commercials. A longitudinal analysis of consumer opinion related to the 1998, 2000, 2002, 2004, and 2006 Super Bowls provides empirical evidence that questions the ability of Super Bowl sponsorship to influence the sales of sponsor offerings. Results pertaining to consumers’ intent to purchase sponsors’ products—one of the most sought after metrics in relating sponsorship effectiveness to sales—demonstrate that levels of intent-to-purchase inspired by sponsorship of the Super Bowl is relatively low and, most importantly, that increases are not being achieved over time. These findings have implications for both mega-sponsees and their sponsors as well as media enterprise diffusing mega-special-events. As large global properties such as the Olympic Games, the FIFA World Cup, the Super Bowl, the World’s Fair, Mardi Gras, Wimbledon, the Running of the Bulls (Pamplona), and the Tour de France become central elements of an emerging culture O’Reilly is with the School of Sports Administration, Faculty of Management, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Canada P3E 2C6. -

Annual Report 2019 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 CONTENTS PAGE PRESIDENT'S REVIEW 8 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 12 AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 20 OLYMPISM IN THE COMMUNITY 26 OLYMPIAN SERVICES 38 TEAMS 46 ATHLETE AND NATIONAL FEDERATION FUNDING 56 FUNDING THE AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIC MOVEMENT 60 AUSTRALIA’S OLYMPIC PARTNERS 62 AUSTRALIA’S OLYMPIC HISTORY 66 CULTURE AND GOVERNANCE 76 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 88 AOF 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 119 CHAIR'S REVIEW 121 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 128 Australian Olympic Committee Incorporated ABN 33 052 258 241 REG No. A0004778J Level 4, Museum of Contemporary Art 140 George Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 P: +61 2 9247 2000 @AUSOlympicTeam olympics.com.au Photos used in this report are courtesy of Australian Olympic Team Supplier Getty Images. 3 OUR ROLE PROVIDE ATHLETES THE OPPORTUNITY TO EXCEL AT THE OLYMPIC GAMES AND PROMOTE THE VALUES OF OLYMPISM AND BENEFITS OF PARTICIPATION IN SPORT TO ALL AUSTRALIANS. 4 5 HIGHLIGHTS REGIONAL GAMES PARTNERSHIPS OLYMPISM IN THE COMMUNITY PACIFIC GAMES ANOC WORLD BEACH GAMES APIA, SAMOA DOHA, QATAR 7 - 20 JULY 2019 12 - 16 OCTOBER 2019 31PARTNERS 450 SUBMISSIONS 792 COMPLETED VISITS 1,022 11SUPPLIERS STUDENT LEADERS QLD 115,244 FROM EVERY STATE STUDENTS VISITED AND TERRITORY SA NSW ATHLETES55 SPORTS6 ATHLETES40 SPORTS7 ACT 1,016 26 SCHOOL SELECTED TO ATTEND REGISTRATIONS 33 9 14 1 4LICENSEES THE NATIONAL SUMMIT DIGITAL OLYMPIAN SERVICES ATHLETE CONTENT SERIES 70% 11,160 FROM FOLLOWERS Athlete-led content captured 2018 at processing sessions around 166% #OlympicTakeOver #GiveThatAGold 3,200 Australia, in content series to be 463,975 FROM OLYMPIANS published as part of selection IMPRESSIONS 2018 Campaign to promote Olympic CONTACTED announcements. -

Stealth Marketing As a Strategy

Business Horizons (2010) 53, 69—79 www.elsevier.com/locate/bushor Stealth marketing as a strategy Abhijit Roy *, Satya P. Chattopadhyay Kania School of Management, University of Scranton, 320 Madison Avenue, Scranton, PA 18510, U.S.A. KEYWORDS Abstract Stealth marketing has gained increasing attention as a strategy during the Stealth marketing; past few years. We begin by providing a brief historical review to provide some Typology; perspective on how this strategy has been practiced in a myriad of ways in various Market orientation; parts of the world, and how it has consequently evolved in the emerging new Ethical considerations; marketplace. A more inclusive definition of stealth marketing is then proposed to Social responsibility conceptually understand its use in various contexts. Specifically, we propose a new typology of stealth marketing strategies based on whether businesses or competitors are aware of them, and whether they are visible to the targeted customers. We further provide suggestions of how firms can counter the stealth marketing strategies used by their competitors. Contrary to conventional wisdom, evidence is also provided about how such strategies can be used for ‘‘doing good’’ for society. Finally, the assessment of efficiency and effectiveness of stealth marketing strategies, and their related ethical implications, are discussed. # 2009 Kelley School of Business, Indiana University. All rights reserved. 1. Responding to challenges the daunting task of making the appropriate adjust- ments to meet these new and emerging needs. Marketing in the new millennium continues to pres- Simultaneously, the marketplace continues to be- ent challenges and opportunities for organizations. come crowded, and marketers are finding it more The new consumer who is emerging today is challenging to be heard and seen above the crowd. -

Media Kit Contents

2005 IAAF World Outdoor Track & Field Championship in Athletics August 6-14, 2005, Helsinki, Finland Saturday, August 06, 2005 Monday, August 08, 2005 Morning session Afternoon session Time Event Round Time Event Round Status 10:05 W Triple Jump QUALIFICATION 18:40 M Hammer FINAL 10:10 W 100m Hurdles HEPTATHLON 18:50 W 100m SEMI-FINAL 10:15 M Shot Put QUALIFICATION 19:10 W High Jump FINAL 10:45 M 100m HEATS 19:20 M 10,000m FINAL 11:15 M Hammer QUALIFICATION A 20:05 M 1500m SEMI-FINAL 11:20 W High Jump HEPTATHLON 20:35 W 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 12:05 W 3000m Steeplechase HEATS 21:00 W 400m SEMI-FINAL 12:45 W 800m HEATS 21:35 W 100m FINAL 12:45 M Hammer QUALIFICATION B Tuesday, August 09, 2005 13:35 M 400m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 13:55 W Shot Put HEPTATHLON 11:35 M 100m DECATHLON\ Afternoon session 11:45 M Javelin QUALIFICATION A 18:35 M Discus QUALIFICATION A 12:10 M Pole Vault QUALIFICATION 18:40 M 20km Race Walking FINAL 12:20 M 200m HEATS 18:45 M 100m QUARTER-FINAL 12:40 M Long Jump DECATHLON 19:25 W 200m HEPTATHLON 13:20 M Javelin QUALIFICATION B 19:30 W High Jump QUALIFICATION 13:40 M 400m HEATS 20:05 M Discus QUALIFICATION B Afternoon session 20:30 M 1500m HEATS 14:15 W Long Jump QUALIFICATION 20:55 M Shot Put FINAL 14:25 M Shot Put DECATHLON 21:15 W 10,000m FINAL 17:30 M High Jump DECATHLON 18:35 W Discus FINAL Sunday, August 07, 2005 18:40 W 100m Hurdles HEATS Morning session 19:25 M 200m QUARTER-FINAL 11:35 W 20km Race Walking FINAL 20:00 M 3000m Steeplechase FINAL 11:45 W Discus QUALIFICATION 20:15 M Triple Jump QUALIFICATION -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 75-3121

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Book Chapter Reference

Book Chapter Athletes & Social Media: What constitutes Ambush Marketing in the Digital Age ? The Case of Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter DE WERRA, Jacques Reference DE WERRA, Jacques. Athletes & Social Media: What constitutes Ambush Marketing in the Digital Age ? The Case of Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter. In: Trigo Trindade, Rita ; Bahar, Rashid ; Neri-Castracane, Giulia. Vers les sommets du droit : "Liber amicorum" pour Henry Peter. Genève : Schulthess éditions romandes, 2019. p. 3-24 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:135051 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 ∗ DE WERRA JACQUES Athletes & Social Media : What constitutes Ambush Marketing in the Digital Age ? The Case of Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter Table of Contents Page Introduction .................................................................................................................... 4 I. Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter and its implementation .......................... 5 A. Rule 40 and the Rule 40 Guidelines ............................................................. 5 B. The Rule 40 waiver system ........................................................................... 7 C. The national implementation of the Rule 40 system ................................. 8 II. Challenges against Rule 40 in Germany ..................................................... 10 A. The administrative antitrust proceedings ................................................ 10 B. The Commitment Decision of the Bundeskartellamt -

Asia's Olympic

Official Newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia Edition 51 - December 2020 ALL SET FOR SHANTOU MEET THE MASCOT FOR AYG 2021 OCA Games Update OCA Commi�ee News OCA Women in Sport OCA Sports Diary Contents Inside Sporting Asia Edition 51 – December 2020 3 President’s Message 10 4 – 9 Six pages of NOC News in Pictures 10 – 12 Inside the OCA 13 – 14 OCA Games Update: Sanya 2020, Shantou 2021 15 – 26 Countdown to 19th Asian Games 13 16 – 17 Two years to go to Hangzhou 2022 18 Geely Auto chairs sponsor club 19 Sport Climbing’s rock-solid venue 20 – 21 59 Pictograms in 40 sports 22 A ‘smart’ Asian Games 27 23 Hangzhou 2022 launches official magazine 24 – 25 Photo Gallery from countdown celebrations 26 Hi, Asian Games! 27 Asia’s Olympic Era: Tokyo 2020, Beijing 2022 31 28 – 31 Women in Sport 32 – 33 Road to Tokyo 2020 34 – 37 Obituary 38 News in Brief 33 39 OCA Sports Diary 40 Hangzhou 2022 Harmony of Colours OCA Sponsors’ Club * Page 02 President’s Message OCA HAS BIG ROLE TO PLAY IN OLYMPIC MOVEMENT’S RECOVERY IN 2021 Sporting Asia is the official newsletter of the Olympic Council of Asia, published quarterly. Executive Editor / Director General Husain Al-Musallam [email protected] Director, Int’l & NOC Relations Vinod Tiwari [email protected] Director, Asian Games Department Haider A. Farman [email protected] Editor Despite the difficult circumstances we Through our online meetings with the Jeremy Walker [email protected] have found ourselves in over the past few games organising committees over the past months, the spirit and professionalism of our few weeks, the OCA can feel the pride Executive Secretary Asian sports family has really shone behind the scenes and also appreciate the Nayaf Sraj through. -

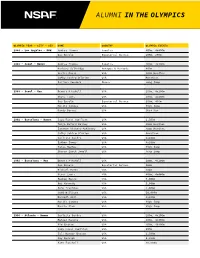

Alumni in the Olympics

ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS 1984 - Los Angeles - M&W Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m, 200m 1988 - Seoul - Women Andrea Thomas Jamaica 400m, 4x400m Barbara Selkridge Antigua & Barbuda 400m Leslie Maxie USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Juliana Yendork Ghana Long Jump 1988 - Seoul - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 200m, 400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Randy Barnes USA Shot Put 1992 - Barcelona - Women Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 1,500m Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeene Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Cathy Schiro O'Brien USA Marathon Carlette Guidry USA 4x100m Esther Jones USA 4x100m Tanya Hughes USA High Jump Sharon Couch-Jewell USA Long Jump 1992 - Barcelona - Men Dennis Mitchell USA 100m, 4x100m Gus Envela Equatorial Guinea 100m Michael Bates USA 200m Steve Lewis USA 400m, 4x400m Reuben Reina USA 5,000m Bob Kennedy USA 5,000m John Trautman USA 5,000m Todd Williams USA 10,000m Darnell Hall USA 4x400m Hollis Conway USA High Jump Darrin Plab USA High Jump 1996 - Atlanta - Women Carlette Guidry USA 200m, 4x100m Maicel Malone USA 400m, 4x400m Kim Graham USA 400m, 4X400m Suzy Favor Hamilton USA 800m Juli Henner Benson USA 1,500m Amy Rudolph USA 5,000m Kate Fonshell USA 10,000m ALUMNI IN THE OLYMPICS OLYMPIC YEAR - CITY - SEX NAME COUNTRY OLYMPIC EVENTS Ann-Marie Letko USA Marathon Tonja Buford Bailey USA 400m Hurdles Janeen Vickers-McKinney USA 400m Hurdles Shana Williams -

Ambush Marketing-The Problem and the Projected Solutions Vis-A-Vis

Journal of Intellectual Property Rights Vol 8, September 2003, pp 375-388 Ambush Marketing−The Problem and the Projected Solutions vis-a-vis Intellectual Property Law−A Global Perspective Sudipta Bhattacharjee The National University of Juridical Sciences,N U J S Bhawan 12 L B Block, Sector-III, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700098 (Received 11 May 2003) The problem of ambush marketing has been plaguing the organizers of various sporting and other events for the last four to five years. Due to the enormous financial losses caused by ambush marketing, the sponsors have been reconsidering the decisions to shell out astronomical sums for sponsoring various events. This paper analyses in great detail the concept of ambush marketing to its genesis, the various famous incidents of ambush marketing and the consequential losses and evaluates the existing intellectual property regime in combating this menace. It also analyses the various sui generis legislations framed by countries like South Africa and Australia to combat ambush marketing and tries to cull out a suitable anti-ambush marketing legislative policy for the Indian scenario. ‘Ambush marketing’ has assumed great legitimate sponsorship, their claims often importance in the modern advertising and provide no basis for legal action. This marketing terminology. In 1996, soft article examines instances of alleged drinks giant, Coke, paid a fortune for the ambushes and how these fit within a right to call itself the official sponsor of wider legal framework. Ambushing the World Cup. Rival Pepsi promptly appears to encompass legitimate launched a massive advertising blitz, competitive behaviour to passing-off and based on the catch line: Nothing official misuse of trademarks. -

Ambush Marketing: the Undeserved Advantage

Ambush Marketing: The Undeserved Advantage Michael Payne International Olympic Committee ABSTRACT The Olympic Games, as the world's largest and most prestigious sports event, has heen a m^jor target for amhush marketing activity. The position of the Intemational Oljonpic Committee is that the practice of amhush marketing represents a deliherate attempt to mislead consumers into helieving that the companies involved are supporters of the Olympic Games. The opposite is in fact the case. The activities of amhushers erode the integrity of msgor events and may potentially lessen the benefits to official sponsors, who are the real supporters of such events. Amhush marketing hreaches one of the fundamental tenets of husiness activity, namely, truth in advertising and husiness communications. The IOC, as custodian of the Olympic Games, successfully adopts a twofold strategy of protection and prevention to counter the threat of amhush marketing. © 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The sponsorship of sport is big business. It is an important revenue source for the owners of major sports events, and it simultaneously pro- vides considerable commercial advantages to sponsors who choose to associate with those events. The scales of the revenues involved can be seen from recent market reports. Sponsorship Research International reported the value ofthe worldwide sponsorship market at $16.57 bil- lion in 1996 (Sponsorship Research Institute, 1997), and sponsorship expenditure in the U.S. market for 1996 was reported at $5.5 billion (International Event Group, 1997). The increasing level of investment is testimony to corporate belief in sponsorship's ability to perform mar- Psychology & Marketing Vol. 15(4):323-331 (July 1998) © 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.