Fort Stewart 12: a Survey of a Portion of Natural Resource Management Unit D7.2, Fort Stewart, Liberty County, Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream-Temperature Characteristics in Georgia

STREAM-TEMPERATURE CHARACTERISTICS IN GEORGIA By T.R. Dyar and S.J. Alhadeff ______________________________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4203 Prepared in cooperation with GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION Atlanta, Georgia 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 3039 Amwiler Road, Suite 130 Denver Federal Center Peachtree Business Center Box 25286 Atlanta, GA 30360-2824 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . 1 Purpose and scope . 2 Previous investigations. 2 Station-identification system . 3 Stream-temperature data . 3 Long-term stream-temperature characteristics. 6 Natural stream-temperature characteristics . 7 Regression analysis . 7 Harmonic mean coefficient . 7 Amplitude coefficient. 10 Phase coefficient . 13 Statewide harmonic equation . 13 Examples of estimating natural stream-temperature characteristics . 15 Panther Creek . 15 West Armuchee Creek . 15 Alcovy River . 18 Altamaha River . 18 Summary of stream-temperature characteristics by river basin . 19 Savannah River basin . 19 Ogeechee River basin. 25 Altamaha River basin. 25 Satilla-St Marys River basins. 26 Suwannee-Ochlockonee River basins . 27 Chattahoochee River basin. 27 Flint River basin. 28 Coosa River basin. 29 Tennessee River basin . 31 Selected references. 31 Tabular data . 33 Graphs showing harmonic stream-temperature curves of observed data and statewide harmonic equation for selected stations, figures 14-211 . 51 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. Map showing locations of 198 periodic and 22 daily stream-temperature stations, major river basins, and physiographic provinces in Georgia. -

2017 Altamaha Regional Water Plan

2017 REGIONAL WATER PLAN ALTAMAHA REGION BACKGROUND The Altamaha Regional Water Plan was initially completed in 2011 and subsequently updated in 2017. The plan outlines near-term and long-term Counties: Appling, Bleckley, strategies to meet water needs through 2050. The Altamaha River, formed Candler, Dodge, Emanuel, by the confluence of the Ocmulgee and Oconee Rivers, is the major surface Evans, Jeff Davis, Johnson, water feature in the region. The Altamaha Region encompasses several Montgomery, Tattnall, Telfair, Toombs, Treutlen, Wayne, major population centers including Vidalia, Jesup, Swainsboro, Eastman, Wheeler, Wilcox and Glennville. OVERVIEW OF ALTAMAHA REGION The Altamaha Region includes 16 counties in the south central portion of Georgia. Over the next 35 years, the population of the region is projected to increase from approximately 256,000 to 285,000 residents. Key economic drivers in the region include agriculture, forestry, professional and business services, education, healthcare, manufacturing, public administration, fishing and hunting, and construction. KEY WATER RESOURCE ISSUES Groundwater (the majority from the Floridan aquifer) is forecasted to meet about 70% ADDRESSED BY THE COUNCIL of the water supply needs, with agricultural and industrial uses being the dominant 1. Current and future groundwater demand sectors. Surface water is utilized to meet about 30% of the forecasted water supplies for municipal/domestic, supply needs, with agriculture and energy as the dominant demand sectors. The industrial and agricultural water use energy sector is a major user of surface water from the Altamaha River. 2. Sufficient surface water quantity and quality to accommodate current and ALTAMAHA future surface water demands WATER 3. Low dissolved oxygen and other PLANNING water quality issues in streams during REGION periods of low flow 4. -

Chemical Character of Surface Waters of Georgia

SliEU' :\0..... / ........ RO O ~ l NO. ···- ··-<~ ......... U )'On no l~er need this publication write to the Geological Sur»ey in Washlndon for ali official maillne label to use In returning it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA Prepared In cooperation wilh the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF 'l'HE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 889- E ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 889-E CHEMICAL CHARACTER OF SURFACE WATERS OF GEORGIA BY WILLIAM L. LAMAR Prepared in cooperation with the DIVISION OF MINES, MINING, AND GEOLOGY OF THE GEORGIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Contributions to the Hydrology of the United States, 19~1-!3 (Pages 317- 380) UN ITED STATES GOVEHNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1944 For sct le Ly Ll w S upcrinkntlent of Doc uments, U. S. Gover nme nt Printing Office, " ' asbingtou 25, D . C. Price 15 ce nl~ CONTENTS Page- Abstract ___________________________________________ -----_--------- 31 T Introduction __________________ c ________________________________ -- _ 317 Physiography_____________________________________________________ 318 Climate__________________________________________________________ 820 Collection and examination of samples_______________________________ 323 Stream flow __________________________ --------- ___________ c ________ . 324 Rainfall and discharge during sampling years_____________________ -

Archaeological Testing at Allenbrook (9Fu286), Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, Roswell, Georgia

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TESTING AT ALLENBROOK (9FU286), CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, ROSWELL, GEORGIA Chicora Research Contribution 547 ARCHAEOLOGICAL TESTING AT ALLENBROOK (9FU286), CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER NATIONAL RECREATION AREA, ROSWELL, GEORGIA Prepared By: Michael Trinkley, Ph.D. Debi Hacker Prepared For: National Park Service Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area 1978 Island Ford Parkway Atlanta, Georgia 30350 Contract No. P11PC50748 ARPA Permit No. CHAT 2012-001 CHICORA RESEARCH CONTRIBUTION 547 Chicora Foundation, Inc. PO Box 8664 Columbia, SC 29202 803-787-6910 www.chicora.org December 3, 2012 This report is printed on permanent paper ∞ MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The investigations were conducted in saprolite rock that was designated Level 2 and compliance with ARPA Permit CHAT 2012-001 extended from 0.07 to 0.17m bs. This zone under contract with the National Park Service to represented fill and no artifacts were identified. examine archaeological features that may be associated with the foundation wall of the Level 3 was slightly deeper, extending Allenbrook House (9FU286, CHAT-98) and from 0.17 to 0.35m and consisted of identical determine if archaeological evidence of a previous compact mottled red (2.5YR 4/4) clay and porch on the south façade of the structure could saprolite rock that graded into a red clay (2.5YR be identified. 4/6) and saprolite rock. This fill was also sterile. The work was conducted by Dr. Michael Level 4 extended from 0.35 to 0.48m and Trinkley, RPA (who was on-site during the entire consisted of red clay (2.5YR 4/6) and saprolite project), Ms. Debi Hacker, and Mr. -

Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College Version June 20, 2012

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version June 20, 2012 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation. The articles use a variety of measurements. Some useful conversions: 1”=2.54 -

Long Range Transportation Plan

Long Range Transportation Plan Prepared by RS&H For the Hinesville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (HAMPO) In cooperation with: Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, Georgia Department of Transportation, Liberty County, Long County, and the Cities of Allenhurst, Flemington, Gum Branch, Hinesville, Midway, Riceboro, Walthourville Adopted on October 14, 2010 Amended June 14, 2012 (incorporated by reference the changes made by the adoption of HAMPO’s FY 2013-2016 Transportation Improvement Plan, see resolution on page 2) Amendment #1: As stated in the last paragraph of the resolution above, HAMPO’s FY 2013-2016 TIP is hereby incorporated into this document. The FY 2013-2016 TIP is attached as Appendix F. METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION A RESOLUTION ADOPTING THE 2035 LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN AS THE OFFICIAL LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN FOR LIBERTY COUNTY WHEREAS, federal regulations for urban transportation planning issued in October 1993, require that the Metropolitan Planning Organization, in cooperation with participants in the planning process, develop and update the Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) every five years; and WHEREAS, the Hinesville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization has been designated by the Governor as the Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) of the Hinesville urbanized area; and WHEREAS, the Hinesville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization, in accordance with federal requirements for a Long Range Transportation Plan, has developed a twenty-year integrated plan -

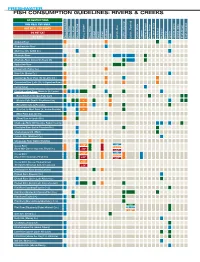

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Archeology Inventory Table of Contents

National Historic Landmarks--Archaeology Inventory Theresa E. Solury, 1999 Updated and Revised, 2003 Caridad de la Vega National Historic Landmarks-Archeology Inventory Table of Contents Review Methods and Processes Property Name ..........................................................1 Cultural Affiliation .......................................................1 Time Period .......................................................... 1-2 Property Type ...........................................................2 Significance .......................................................... 2-3 Theme ................................................................3 Restricted Address .......................................................3 Format Explanation .................................................... 3-4 Key to the Data Table ........................................................ 4-6 Data Set Alabama ...............................................................7 Alaska .............................................................. 7-9 Arizona ............................................................. 9-10 Arkansas ..............................................................10 California .............................................................11 Colorado ..............................................................11 Connecticut ........................................................ 11-12 District of Columbia ....................................................12 Florida ........................................................... -

Whittaker-Annotated Atlbib July 31 2014

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version of August 2, 2014 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. I try in particular to note problems in some of the studies that are often cited by others with less atlatl knowledge, and correct some of the misinformation. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation, but at heart I am an old-fashioned paper-lover. -

An Assessment of Lithic Extraction Technology at a Metavolcanic Quarry in the Slate Belt of North Carolina

An Assessment of Lithic Extraction Technology at a Metavolcanic Quarry in the Slate Belt of North Carolina by Lawrence E. Abbott, Jr. Abstract The Three Hat Mountain Quarry, 31DV51, is located in Davidson County, North Carolina. Prehistoric groups used this quarry as a rich and variable source of metavolcanic raw materials, which included rhyodacites and tuffs. Excavations at the site revealed stratified deposits of cultural materials. This paper will present a comparative assessment of these materials and will address issues regarding changes in extraction technology, reduction strategies, and modes of distribution over time. Particular attention will be given to how the differences in raw material types across the quarry may have affected the technological aspects of procurement and initial processing strategies. In North Carolina we are both blessed and cursed at the same time. We are blessed in the fact that a major portion of the Piedmont Region of the state lies within the Carolina Slate Belt. The Slate Belt is a region of numerous metavolcanic outcrops, which supported prehistoric people with an abundance of knappable raw materials. As a result, the area is littered with prehistoric quarry sites. We are cursed in the fact that very little work has been undertaken on any of these quarries. Quarry studies in North Carolina is still in its infancy (Abbott 2003). Few detailed studies have been made at specific quarries. In this paper I will attempt to address several issues related to quarry studies, lithic resource procurement and distribution based on some of the information at hand. I will focus my discussion on a specific quarry site (31DV51, Three Hat Mountain) located in Davidson County, North Carolina. -

Military Bases

Dade Catoosa Fannin Towns Rabun Murray Union Whitfield Walker Gilmer Habersham Georgia Military White Lumpkin Stephens Gordon Chattooga Pickens Bases Dawson Franklin Banks Hart Bartow Hall Floyd Cherokee Forsyth Jackson Dobbins Madison Elbert Polk Air Reserve Base Barrow Clarke Gwinnett Oglethorpe Paulding Cobb Oconee Haralson DeKalb Walton Wilkes Lincoln Douglas Fort McPherson* Rockdale Fulton Morgan Greene Carroll Fort Gillem* Taliaferro Columbia Clayton Newton McDuffie Henry Warren Coweta Fayette Richmond Heard Fort Gordon Spalding Putnam Jasper Butts Hancock Glascock Pike Lamar Monroe Baldwin Troup Meriwether Jones Burke Jefferson Washington Upson Bibb Wilkinson Jenkins Harris Twiggs Talbot Crawford Johnson Screven Robins Taylor Muscogee Peach Air Force Base Emanuel Laurens Marion Houston Bleckley Treutlen Candler Fort Benning Macon Bulloch Effingham Chattahoochee Montgomery Pulaski Schley Dodge Dooly Toombs Evans Bryan Stewart Wheeler Sumter Hunter Army Webster Tattnall Wilcox Telfair Aireld Crisp Chatham Quitman Fort Stewart Terrell Jeff Davis Randolph Lee Appling Turner Ben Hill Long Liberty Clay Irwin Dougherty Calhoun Worth Coffee Bacon Wayne McIntosh Marine Corps Tift Early Baker Logistics Base Albany Atkinson Pierce Berrien Brantley Glynn Miller Mitchell Colquitt Cook Clinch Ware Lanier Seminole Moody Camden Grady Decatur Thomas Brooks Air Force Base Charlton Lowndes Echols Kings Bay Naval Submarine Base Key: Army Air Force Navy Marine Corps *Will close by 9/2011 due to 2005 BRAC Realignment. -

A Complex Web of History and Artifact Types in the Early Archaic Southeast

A COMPLEX WEB OF HISTORY AND ARTIFACT TYPES IN THE EARLY ARCHAIC SOUTHEAST By KARA BRIDGMAN SWEENEY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Kara Bridgman Sweeney 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Most deserving of my acknowledgment are the indigenous American groups who created the archaeological record that forms the basis of this research. I hope that this document will serve as a partial history of the Early Archaic, which so long has been relegated to “prehistory.” I would very much like to thank the numerous individuals who shared their artifact collections and local knowledge with me. I especially want to express appreciation to those artifact collectors who make a concerted effort to share the information they have with archaeologists, and who assist in the recording of archaeological sites. In Alabama, I thank Ed and Richard Kilborn. I would also like to thank Don Marley and Steve Lamb for their contributions, as well as one individual who asked that he not be named in my dissertation (in this document, I have called him “X,” as requested). In South Carolina, I thank Doug Boehme, Darby, Kevin, and Ted Hebert, Gary LeCroy, Earline Mitchum, George Neil, Jimmy Skinner, and Larry Strong. Becky Shuler of the Elloree Heritage Museum and Barbara Butler of the South Carolina Bank and Trust of Elloree deserve thanks for allowing access to artifact collections at their repositories. In Georgia, I thank Danny Greenway, Seaborn Roberts, Danny Ely, Emery Fennell, John Arena, Larry Meadows, Marvin Singletary, and John Whatley.