Effects of D-Allulose on Glucose Tolerance and Insulin Response to A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determining the Effect of Small Doses of Fructose and Its Epimers on Glycemic Control

Determining the Effect of Small Doses of Fructose and its Epimers on Glycemic Control by Jarvis Clyde Noronha A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto © Copyright by Jarvis Clyde Noronha 2017 ii Determining the Effect of Small Doses of Fructose and its Epimers on Glycemic Control Jarvis Clyde Noronha Master of Science Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Toronto 2017 Abstract Given that sugars have emerged as the dominant nutrient of concern in diabetes, there is a need for the development of alternative sweeteners. To assess the role of small doses (5g, 10g) of fructose and allulose on postprandial glucose metabolism, we conducted an acute randomized controlled trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. We found that small doses of allulose, but not fructose, modestly reduced the postprandial glycemic response to a 75g oral glucose load. To assess whether low-dose (< 50-g/day) fructose and all its epimers (allulose, tagatose and sorbose) lead to sustainable improvements in long-term glycemic control, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. The available evidence suggested that fructose and tagatose led to significant reductions in HbA1c and fasting glucose. Our findings highlight the need for long-term randomized controlled trials to confirm the viability of fructose and its epimers as alternative sweeteners. iii Table of Contents Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... -

FDA Finalizes Allulose Guidance and Requests Information on Other Sugars Metabolized Differently Than Traditional Sugars

FDA Finalizes Allulose Guidance and Requests Information on Other Sugars Metabolized Differently Than Traditional Sugars October 19, 2020 Food, Drug, and Device FDA has taken two notable actions regarding the sugars declaration in the Nutrition Facts Label (NFL) and Supplement Facts Label (SFL). On Friday, the agency released a final guidance regarding the declaration of allulose, confirming that this monosaccharide need not be included in the declaration of “Total Sugars” or “Added Sugars,” though it must be included in the “Total Carbohydrates” declaration in the NFL. Today, FDA published a Federal Register notice requesting information about and comments on the nutrition labeling of other sugars that are metabolized differently than traditional sugars. We briefly summarize both documents below to help inform stakeholder comments on the notice, which are due to FDA by December 18, 2020. Allulose Final Guidance Allulose, or D-psicose, is a monosaccharide that can be used as a substitute for traditional sugar in food and beverage products. For purposes of nutrition labeling, FDA has generally 1 defined nutrients based on their chemical structure.0F Accordingly, when FDA updated its NFL and SFL regulations in 2016, the agency reiterated the definition of “Total Sugars” as the sum of 2 all free monosaccharides and disaccharides (e.g. glucose, fructose, and sucrose).1F FDA also added to these regulations a definition of “Added Sugars” – sugars added during the processing 3 of food, or packaged as such – and required their declaration in the NFL and SFL.2F Although the agency recognized that there are sugars that are metabolized differently than traditional sugars, FDA did not make a determination at that time as to whether allulose should be excluded from “Total Carbohydrate,” “Total Sugars,” or “Added Sugars” Declarations. -

Natural Alternative Sweeteners and Diabetes Management

Current Diabetes Reports (2019) 19:142 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1273-8 LIFESTYLE MANAGEMENT TO REDUCE DIABETES/CARDIOVASCULAR RISK (B CONWAY AND H KEENAN, SECTION EDITORS) Natural Alternative Sweeteners and Diabetes Management Emily Mejia1 & Michelle Pearlman2 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review The goal of this review is to discuss the data on natural alternative sweeteners and their effects on glucose homeostasis and other metabolic parameters within the past five years. We sought to answer whether common natural alternative sweeteners have a positive or negative effect on glucose control in both human and animal models, and whether the data supports their widespread use as a tool to help reduce the prevalence of diabetes and associated comorbid conditions. Recent Findings Recent studies suggest that natural alternative sweeteners may reduce hyperglycemia, improve lipid metabo- lism, and have antioxidant effects particularly in those that have baseline diabetes. Summary Diabetes and metabolic syndrome have become a global healthcare crisis and the sugar overconsumption plays a major role. The use of artificial sweeteners has become more prevalent to improve insulin resistance in those with diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, although the evidence does not support this result. There are however some promising data to suggest that natural alternative sweeteners may be a better alternative to sugar and artificial sweeteners. Keywords Natural alternative sweeteners . Diabetes . Stevia . Sugar alcohols . Rare sugars Introduction retinopathy, nephropathy, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cardiovascular disease [2–4]. Type 2 Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder that results DM (T2DM) often coexists with other metabolic disorders from glucose dysregulation. -

Calorie Restriction Mimetics: Upstream-Type Compounds for Modulating Glucose Metabolism

nutrients Review Calorie Restriction Mimetics: Upstream-Type Compounds for Modulating Glucose Metabolism Hideya Shintani 1 , Tomoya Shintani 2,* , Hisashi Ashida 3 and Masashi Sato 4 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Saiseikai Izuo Hospital, Osaka 551-0032, Japan; [email protected] 2 United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Ehime University, Matsuyama 790-8577, Japan 3 Faculty of Biology-Oriented Science and Technology, Kindai University, Wakayama 649-6493, Japan; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Agriculture, Kagawa University, Kagawa 761-0701, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-6-6621-5122 Received: 6 November 2018; Accepted: 18 November 2018; Published: 22 November 2018 Abstract: Calorie restriction (CR) can prolong the human lifespan, but enforcing long-term CR is difficult. Therefore, a compound that reproduces the effect of CR without CR is needed. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on compounds with CR mimetic (CRM) effects. More than 10 compounds have been listed as CRMs, some of which are conventionally categorized as upstream-type CRMs showing glycolytic inhibition, while the others are categorized as downstream-type CRMs that regulate or genetically modulate intracellular signaling proteins. Among these, we focus on upstream-type CRMs and propose their classification as compounds with energy metabolism inhibition effects, particularly glucose metabolism modulation effects. The upstream-type CRMs reviewed include chitosan, acarbose, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, and hexose analogs such as 2-deoxy-D-glucose, D-glucosamine, and D-allulose, which show antiaging and longevity effects. Finally, we discuss the molecular definition of upstream-type CRMs. -

D-Allulose Is a Substrate of Glucose Transporter Type 5 (GLUT5) in the Small Intestine

Food Chemistry 277 (2019) 604–608 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Chemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchem D-Allulose is a substrate of glucose transporter type 5 (GLUT5) in the small intestine T ⁎ Kunihiro Kishidaa, , Gustavo Martinezb, Tetsuo Iidac, Takako Yamadac, Ronaldo P. Ferrarisb,1, Yukiyasu Toyodad,1 a Department of Science and Technology on Food Safety, Kindai University, 930 Nishimitani, Kinokawa, Wakayama 649-6493, Japan b Department of Pharmacology, Physiology, and Neurosciences, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 185 S. Orange Avenue, Newark, NJ 07101-1749, USA c Research and Development, Matsutani Chemical Industry Company, Limited, 5-3 Kita-Itami, Itami, Hyogo 664-8508, Japan d Department of Pathobiochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Meijo University, 150 Yagotoyama, Tempaku-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 468-8503, Japan ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: D-Allulose has been reported to have beneficial health effects. However, the transport system(s) mediating in- D-Allulose testinal D-allulose transport has not yet been clearly identified. The aim of this study was to investigate whether Intestinal absorption intestinal D-allulose transport is mediated by glucose transporter type 5 (GLUT5). When D-allulose alone was GLUT5 gavaged, plasma D-allulose levels were dramatically higher in rats previously fed fructose. This suggests en- hanced intestinal D-allulose absorption paralleled increases in GLUT5 expression observed only in fructose-fed rats. When D-allulose was gavaged with D-fructose, previously observed increases in plasma D-allulose levels were dampened and delayed, indicating D-fructose inhibited transepithelial D-allulose transport into plasma. Tracer D- 14 [ C]-fructose uptake rate was reduced to 54.8% in 50 mM D-allulose and to 16.4% in 50 mM D-fructose, sug- 14 gesting D-allulose competed with D-[ C]-fructose and the affinity of D-allulose for GLUT5 was lower than that of D-fructose. -

GRAS Notifications to FDA – a Review of Ingredients with Intended Use In

GRAS Ingredients for Use in Medical Foods GRAS Ingredients for Use in Medical Foods: An Overview of FDA Regulation Ginny Bank, Cheryl Dicks, MS, RAC 1 © GRAS Associates 2016 www.gras-associates.com GRAS Ingredients for Use in Medical Foods Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................... 3 FDA Medical Food Regulation Overview ........................................................ 4 GRAS Notifications to FDA – A Review of Ingredients with Intended Use in Medical Foods ................................................................................................. 6 Ready to seek GRAS status for your medical food ingredient? ................. 11 Regulatory Services Include: ..................................................................... 11 Uncover greater market opportunities for your ingredient ......................... 12 Contact GRAS Associates today ............................................................... 12 Appendix A – Summary of GRAS Notifications Submitted to FDA for Ingredients Intended for Use in Medical Foods .......................................... 13 2 © GRAS Associates 2016 www.gras-associates.com GRAS Ingredients for Use in Medical Foods Introduction The medical food arena is a growing specialty product category that presents food and dietary supplement manufactures with interesting business opportunities for market expansion of an ingredient or final product. The Business Insights: The Emerging Market for Medical Foods Nutraceuticals -

D-Psicose Nutrasource, Inc.Inc

ORIGINAL SUBMISSION 000001 GRAS exemption claim for D-psicose NutraSource, Inc.Inc. August 18,18, 20112011 Dr. Susan CarlsonCarlson Division ofof BiotechnologyBiotechnology andand GRASGRAS NoticeNotice ReviewReview Office of Food AdditiveAdditive Safety-CFSANSafety-CFSAN U.S. Food andand DrugDrug AdministrationAdministration 5100 Paint Branch ParkwayParkway (HFS-255)(HFS-255) College Park, MDMD 20740-383520740-3835 DiVisionDivision of BiotechnologyBiotechnology and GRAS Notice ReviewReview Re: GRAS exemption claimclaim forfor D-psicoseD-psicose asas anan ingredientingredient inin foodsfoods Dear Dr. Carlson,Carlson, This is to notify you that CJCJ CheiljedangCheiljedang (based(based inin S.S. Korea)Korea) claimsclaims thatthat thethe useuse ofof thethe substance described below (D-psicose) is exempt fromfrom the the premarketpremarket approvalapproval requirementsrequirements ofof the Federal Food, Drug, and CosmeticCosmetic ActAct becausebecause CJCJ AmericaAmerica hashas determineddetermined suchsuch useuse toto bebe Generally Recognized AsAs SafeSafe (GRAS).(GRAS). On behalf ofCJof CJ Cheiljedang, NutraSource (an independent consultingconsulting firm)firm) assembledassembled aa panel of experts highly qualified byby scientificscientific trainingtraining andand experienceexperience toto evaluateevaluate thethe safetysafety ofof the intended uses ofofD-psicose. D-psicose. The panel includedincluded Dr.Dr. SusanSusan ChoCho atat NutraSourceNutraSource (Clarksville,(Clarksville, MD), Dr. Joanne Slavin (The University ofof Minnesota,Minnesota, -

Potent Inhibitory Effects of D-Tagatose on the Acid Production and Water-Insoluble Glucan Synthesis of Streptococcus Mutans GS5 in the Presence of Sucrose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Okayama University Scientific Achievement Repository Acta Med. Okayama, 2015 Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 105ン111 CopyrightⒸ 2015 by Okayama University Medical School. Original Article http ://escholarship.lib.okayama-u.ac.jp/amo/ Potent Inhibitory Effects of D-tagatose on the Acid Production and Water-insoluble Glucan Synthesis of Streptococcus mutans GS5 in the Presence of Sucrose Daijo Sawadaa,b*, Takaaki Ogawaa, Minoru Miyakea, Yoshinori Hasuib, Fuminori Yamaguchic, Ken Izumorid, and Masaaki Tokudac,d Departments of aOral and Maxillofacial Surgery and cCell Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kagawa University, Miki, Kagawa 761-0793, Japan, bHasui Dental Family Clinic, Kagawa 761-0704, Japan, dRare Sugar Research Center, Miki, Kagawa 761-0793, Japan We examined and compared the inhibitory effects of D-tagatose on the growth, acid production, and water-insoluble glucan synthesis of GS5, a bacterial strain of Streptococcus mutans, with those of xylitol, D-psicose, L-psicose and L-tagatose. GS5 was cultured for 12h in a medium containing 10オ (w/v) of xylitol, D-psicose, L-psicose, D-tagatose or L-tagatose, and the inhibitory effect of GS5 growth was assessed. Each sugar showed different inhibitory effects on GS5. Both D-tagatose and xylitol significantly inhibited the acid production and water-insoluble glucan synthesis of GS5 in the presence of 1オ (w/v) sucrose. However, the inhibitory effect of acid production by D-tagatose was significantly stronger than that of xylitol in presence of sucrose. Key words: Streptococcus mutans, D-tagatose, xylitol, acid production, water-insoluble glucan he definition of ʻrare sugarsʼ is monosaccha- the most extensively examined rare sugar, including T raides and their derivatives that are not com- anti-diabetes and anti-obesity effects [4-7]. -

GRAS Notice 828, D-Psicose

GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 828 https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-notice-inventory NutraSource, Inc. 6309 Morning Dew Ct, Clarksville, MD 21029 (410)-531 -3336 or (301) 875--6454 November 20, 2018 Dr. Paulette Gaynor Office of Food Additive Safety (HFS-200) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition offlCEOf ~ ~V'c SAfc,' Food and Drug Administration fOOO A0011• 5001 Campus Drive College Park, MD 20740 Subject: GRAS Notification - D-allulose (D-psicose) Dear Dr. Gaynor, On behalf of Samyang Corp., we are submitting a GRAS notification for D-allulose as a food ingredient. The enclosed document ~rovides notice of a claim that the food ingredient, D-allulose described in the enplosed notification is exempt from the premarket approval requirement of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act because it has been determined to be generally recognized as safe (GRAS), based on scientific procedures, for addition to foods. We bel eve that this determination and notification are in compliance with Pursuant to 21 C.F.R. Part 170, subpart E. We enclose an original copy of this notification and a CD Rom containing electronic files for your review. Please feel free to contact me if additional information or clarification is needed as you proceed with the review. We would appreciate your kind attention to this matter. Sincerely, Susan Cho, Ph.D. [email protected] Agent for Samyang Corp. 1 D-Allulose (D-Psicose) GENERALLY RECOGNIZED AS SAFE (GRAS) NOTICE FOR D-ALLULOSE (D-PSICOSE) AS A FOOD INGREDIENT On behalf of Samyang Corp. Prepared by: NutraSource, Inc. -

Sugar Matrix

Based on perfact’s database holding ingredients for over 250,000 products, we found that almost 300 names for sugar that appear on food labels aren’t covered by the “56 names of sugar” and SugarScience’s 61 names of sugar. The exact number depends on how one counts. This document aims to be a basis to help draw the lines between what should be considered “sugar” within the scope of those lists – and what shouldn’t. Diagram elements ANNOTATED ALTERNATIVE NAME Molecular Source Product sugar or sugar alcohol Diagram element constituting a dietary / functional fiber Molecular Source Product sugar or sugar alcohol Diagram elements explicitly ANNOTATED on 56/61 lists ALTERNATIVE NAME Molecular Source Product sugar or sugar alcohol Diagram elements explicitly or implicitly on 56/61 lists (e.g. because listed by one of its alternative name) Molecular Source Product sugar or sugar alcohol Production pathways Most common Less common This is a working document in progress. Current as of February 2019 Polysaccharides Disaccharides Monosaccharides Sugar alcohols Heat under pressure with hydrogen and Raney-nickel Feed with glucose Ribose Ribitol Ribose syrup Ribitol syrup Bacillus spp. Treat with acid E 967 E 460 Xylose Xylitol E 460I, MCC, CELLULOSE GEL, Treat with acid, pulp, and bleach Xylose syrup Xylitol syrup MICROCELLULOSE Heat under pressure with hydrogen and Raney-nickel Woody plant Cellulose Microcrystalline parts cellulose Wood Treat with acid or enzymes Treat with acid, pulp, and bleach Feed with glucose/sucrose Curdlan Agrobacterium Feed -

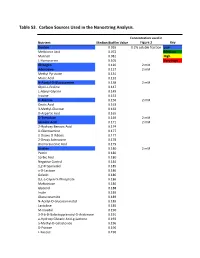

Supplementary Tables Vfinal.Xlsx

Table S3. Carbon Sources Used in the Nanostring Analysis. Concentration used in Nutrient Median Biofilm Value Figure 3 Key Dextrin 0.065 0.2% soluble fraction Low Melibionic Acid 0.072 Medium Mannan 0.081 High L-Homoserine 0.105 Very High Glycogen 0.120 2 mM Adenosine 0.127 2 mM Methyl Pyruvate 0.131 Mucic Acid 0.132 N-Acetyl-D-Glucosamine 0.138 2 mM Glycil-L-Proline 0.147 L-Alanyl-Glycine 0.149 Inosine 0.153 D-Alanine 0.156 2 mM Oxalic Acid 0.163 3-Methyl-Glucose 0.163 D-Aspartic Acid 0.165 D-Trehalose 0.169 2 mM Glycolic Acid 0.171 2 mM 2-Hydroxy Benzoic Acid 0.174 D-Glucosamine 0.177 2-Deoxy-D-Ribose 0.177 2-Deoxy Adenosine 0.178 Bromo Succinic Acid 0.179 Uridine 0.180 2 mM Pectin 0.180 Sorbic Acid 0.180 Negative Control 0.184 1,2-Propanediol 0.185 a-D-Lactose 0.186 Gelatin 0.186 D,L-a-Glycerol-Phosphate 0.186 Maltotriose 0.186 Glycerol 0.188 Inulin 0.189 Glucuronamide 0.189 N-Acetyl-D-Glucosaminatol 0.189 Lactulose 0.189 M-Inositol 0.190 3-0-b-D-Galactopyranosyl-D-Arabinose 0.191 a-Hydroxy Glutaric Acid-g-Lactone 0.193 a-Methyl-D-Galactoside 0.196 D-Psicose 0.196 L-Fucose 0.196 Succinamic Acid 0.197 D-Sorbitol 0.197 2 mM Dulcitol 0.198 D-Fructose-6-Phosphate 0.198 Sedoheptulosa 0.199 Glyoxylic Acid 0.200 Maltose 0.201 2 mM D-Ribono-1,4-Lactone 0.201 Sucrose 0.201 2 mM D-Melibiose 0.202 Mono Methyl Succinate 0.203 N-Acetyl-b-D-Mannosamine 0.204 p-Hydroxy Phenyl Acetic Acid 0.204 L-Rhamnose 0.205 2 mM D-Cellobiose 0.206 D-Glucuronic Acid 0.207 Adonitol 0.207 b-Methyl-D-Glucoside 0.207 Laminarin 0.208 Acetoacetic Acid 0.208 a-Keto-Glutaric -

Effects of the Rare Sugars D-Psicose and D-Tagatose on the Sugar Content and Incidence of Blossom End Rot in Tomato Grown Hydroponically with Salinity Treatment

Original Paper Environ. Control Biol., 52 (3), 155160, 2014 DOI: 10.2525/ecb.52.155 Effects of the Rare Sugars D-psicose and D-tagatose on the Sugar Content and Incidence of Blossom End Rot in Tomato Grown Hydroponically with Salinity Treatment 1 1 1 1 2 2 Yoshihiro YAMADA ,KazumasaKAKIBUCHI , Ayako KOZUKI , Yutaka ISHIDA ,KenIZUMORI , Shigeyuki TAJIMA , 2 3 3 Kazuya AKIMITSU , Takeo OHKOUCHI and Fumito KASAI 1 Shikoku Research Institute Inc., 21098 Yashima-nishimachi, Takamatsu, Kagawa 7610192, Japan 2 Faculty of Agriculture, Kagawa University, 2393 Ikenobe, Miki, Kida, Kagawa 7610795, Japan 3 Mitsui Chemicals Agro Inc., 1358 Ichimiyake, Yasu, Shiga 5202362, Japan (Received March 4, 2014; Accepted June 12, 2014) Low sugar content of fruits in winter, and blossom end rot in summer, are serious problems in the production of tomato with high soluble solids content. In the present study, we investigated the effects of the rare sugars D-psicose and D-tagatose on the sugar content of fruits and incidence of blossom end rot during several cropping seasons. We determined a highly positive correlation between the sugar content and the cumulative solar radiation during the maturation period. Treatment with D-psicose resulted in an increase in the sugar content over every cropping season. It resulted in a reduction in the in- cidence of blossom end rot, a reduction in stomatal conductance, and an increase in the relative water content in summer. On the other hand, it resulted in an increase in the incidence of blossom end rot in winter and rainy season. Treatment with D-tagatose had no effect on the sugar content, incidence of blossom end rot, water potential, stomatal conductance, or rela- tive water content.