Bassenthwaite Vital Uplands DRAFT Baseline Assessment of Ecosystem Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lords Seat, Thornthwaite, Keswick

LORDS SEAT, THORNTHWAITE, KESWICK rightmove.co.uk The UK’s number one property website rural | forestry | environmental | commercial | residential | architectural & project management | valuation | investment | management | dispute resolution | renewable energy LORDS SEAT, THORNTHWAITE, KESWICK, CUMBRIA, CA12 5SG Energy Performance Certificate Lords Seat, Thornthwaite Dwelling type: Semi-detached house KESWICK Date of assessment: 15 March 2010 CA12 5SG Date of certificate: 15 March 2010 Reference number: 9558-8058-6267-7730-7930 Type of assessment: RdSAP, existing dwelling Total floor area: 284 m² This home's performance is rated in terms of energy use per square metre of floor area, energy efficiency based on fuel costs and environmental impact based on carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) emissions. Energy Efficiency Rating Environmental Impact (CO 2 ) Rating Current Potential Current Potential Very energy efficient - lower running costs Very environmentally friendly - lower CO2 emissions (92 plus) (92 plus) (81-91) (81-91) (69-80) (69-80) (55-68) (55-68) (39-54) (39-54) (21-38) (21-38) (1-20) (1-20) Not energy efficient - higher running costs Not environmentally friendly - higher CO 2 emissions EU Directive EU Directive England & Wales 2002/91/EC England & Wales 2002/91/EC The energy efficiency rating is a measure of the The environmental impact rating is a measure of a overall efficiency of a home. The higher the rating home's impact on the environment in terms of the more energy efficient the home is and the carbon dioxide (CO2 ) emissions. The higher the lower the fuel bills are likely to be. rating the less impact it has on the environment. -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

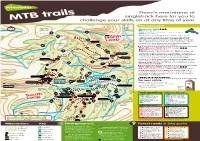

MTB Trails Challenge450 Your Skills on at Any Time of Year

There’s mountains of 150 singletrack here for you to 200 250 300 350 400 450 MTB trails challenge450 your skills on at any time of year. 500 500 Barf 550 Trail information 100 Bassenthwaite 600 Lord’s N Quercus TrailLake • • • Seat Blue moderate. 21 7.5km (4.6miles). 3.5km (2miles) shorter option. 29 23 Start at Cyclewise. This trail is a gem waiting to be discovered. Expect 5 flowing singletrack with gentle berms, rolling jumps, 30 Aiken Beck North 100 wide gradual climbs with technical features for the 7 adventurous riders. Suitable for intermediate mountain The slog Loop bikers withA66 basic off-road skills and reasonable fitness. 500 Ullister Finding your way: Follow the blue arrows on timber Spout Force 28 27 24 Hill 600 8 posts. Look out for any warning markers. Beckstones 18 550 Plantation The Altura Trail North Loop • • • 200 150 500 450 250 300 350 W 400 Red difficult. 10km (6miles). 450 53 C o Black Severe, (optional features). Start at Cyclewise. Darling h m Scawgill 350 54 b 500 Waymarked, with 200 metres height gain of climbing. Bridge How 26 i G Luchini’s view n ill This is a singletrack trail, with steep climbs, twisting turns, Spout Force l Seat 9 exhilaratingThornthwaite descents involving berms, jumps and Car Park How Its a rollover some technical black graded sections as an option. Seat wow Happy days a 3 450 Finding your way: Follow the red arrows on timber posts. W D 16 Lorton r i Look out for any warning markers. Also on this route are l y t l y c b l 10 Fells 450 o Tarbarrel Black grade trail features. -

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

Bassenthwaite Lake (English Lake District)

FRESHWATER FORUM VOLUME 25, 2006 Edited by Karen Rouen SPECIAL TOPIC THE ECOLOGY OF BASSENTHWAITE LAKE (ENGLISH LAKE DISTRICT) by Stephen Thackeray, Stephen Maberly and Ian Winfield Published by the Freshwater Biological Association The Ferry House, Far Sawrey, Ambleside, Cumbria LA22 0LP, UK © Freshwater Biological Association 2006 ISSN 0961-4664 CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................. 3 Introduction ....................................................................................... 5 Catchment characteristics .................................................................. 7 Physical characteristics of Bassenthwaite Lake ................................ 9 Water chemistry ................................................................................ 16 Phytoplankton .................................................................................... 32 Macrophytes ...................................................................................... 39 Zooplankton ...................................................................................... 48 Benthic invertebrates ......................................................................... 52 Fish populations ................................................................................ 52 Birds .................................................................................................. 60 Mammals ........................................................................................... 61 -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

The North Western Fells (581M/1906Ft) the NORTH-WESTERN FELLS

FR CATBELLS OM Swinside THE MAIDEN MOOR Lanthwaite Hill HIGH SPY NORTH Newlands valley FR OM Crummock THE Honister Pass DALE HEAD BARROW RANNERDALE KNOTTS SOUTH Wa Seatoller High Doat Br FR te aithwait r OM CAUSEY PIKE DALE HEAD e HINDSCARTH THE Buttermer GRASMOOR Rosthwaite WHITELESS PIKE EAS BARF HIGH SPY e SALE FELL CA FR T HINDSCARTH S Sleet How TLE OM High Snockrigg SCAR CRAGS CRA ROBINSON WANDOPE Bassenthwait THE LORD’S SEAT G MAIDEN MOOR ROBINSON LING FELL WES EEL CRAG (456m/1496ft) GRISEDALE PIKE Gr e SAIL T ange-in-Borrowdale Hobcarton End 11 Graystones 11 MAIDEN MOOR Buttermer SAIL BROOM FELL ROBINSON EEL CRAG BROOM FELL KNOTT RIGG SALE e FELL LORD’S SEAT HOPEGILL HEAD Ladyside Pike GRAYSTONES ARD CRAGS Seat How WANDOPE CATBELLS LING FELL Der SAIL HINDSCARTH (852m/2795ft) High EEL CRAGS went GRASMOOR SCAR CRAGS Lor Wa WHITESIDE 10 Grasmoor 10 CAUSEY PIKE ton t DALE HEAD WHINLATTER er GRAYSTONES Whinlatter Pass Coledale Hause OUTERSIDE Kirk Fell Honister Swinside BARROW High Scawdel Hobcarton End HOPEGILL HEAD Pass Harrot HIGH SPY GRISEDALE PIKE Swinside Dodd (840m/2756ft) Ladyside Pike GRISEDALE PIKE Br Seatoller High Doat 9 Eel Crag Eel 9 HOPEGILL HEAD aithwait Hobcarton End WHITESIDE CASTLE CRAG e Whinlatter Pass Coledale Hause WHINLATTER THE NORTH- Whinlatter WES GRASMOOR FELL Crummock Seat How (753m/2470ft Forest WANDOPE four gr Par TERN Wa Thirdgill Head Man 8 Dale Head Dale 8 projections k LORD’S SEAT S te of the r r BARF WHITELESS PIKE BROOM FELL aphic KNOTT RIGG ange RANNERDALE KNOTTS Bassenthwait (637m/2090ft) LING FELL -

Download Dodd Wood Walking

96 98 99 99 Lake District Visitor information Osprey Get a bird’s Enjoy your visit Cockermouth Workington A66 Penrith B5292 Project Dodd Wood A66 M6 A66 A591 eye view... Keswick B5289 A partnership project between the Forestry Whitehaven Whinlatter A592 Commission, Lake District National Park and Forest A591 Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) A685 with fantastic support from many volunteers. Dodd Wood is a fantastic place Ambleside A6 Hawkshead B5285 B5286 Windermere A591 The partnership aims to The ospreys have returned A685 to get some amazing views of B5284 Grizedale A593 Kendal Amazing ensure the continued success every year and used different Forest A6684 A592 A5074 of breeding ospreys at nest sites, successfully raising the northern Lake District. A5084 M6 Bassenthwaite, and at least one chick each year. A595 The network of walking trails will take you deep into the A5092 views, A590 to provide visitors to the The project is funded by visitor woodland, and if you are up for it, you can access the Lakes with the opportunity A65 donations, and support from paths that lead to the Skiddaw mountain range. Walk to Ulverston to see and fi nd out Location Parking other partners, but operates the top of Dodd Summit for spectacular views over the Keswick is the nearest town or Start your visit from Dodd Wood fantastic more about ospreys. at a loss which is shared by fells and mountains. village. By Road: From Keswick car park. A pay and display take the A591 towards Bothel. system operates here. A The return of ospreys to the Forestry Commission, RSPB You can also see the magnifi cent Bassenthwaite ospreys Bassenthwaite Lake in 2001 and Lake District National Park. -

Trusmadoor and Other Cumbrian `Pass' Words

Trusmadoor and Other Cumbrian `Pass' Words Diana Whaley University of Newcastle Nobody ever sang the praises of Trusmadoor, and it's time someone did. This lonely passage between the hills, an obvious and easy way for man and beast and beloved by wheeling buzzards and hawks, has a strange nostalgic charm. Its neat and regular proportions are remarkable—a natural `railway cutting'. What a place for an ambush and a massacre!1 No ambushes or massacres are promised in the following pages, but it will be argued that the neglected name of Trusmadoor holds excitements of a quieter kind. I will consider its etymology and wider onomastic and historical context and significance, and point to one or possibly two further instances of its rare first element. In the course of the discussion I will suggest alternative interpretations of two lost names in Cumbria. Trusmadoor lies among the Uldale Fells in Cumbria, some five miles east of the northern end of Bassenthwaite Lake (National Grid Reference NY2733). An ascending defile, it runs south-east, with Great Cockup to its west and Meal Fell to the north-east. The top of the pass forms a V-shaped frame for splendid views north over the Solway Firth some twenty miles away. Trusmadoor is a significant enough landscape feature to appear on the Ordnance Survey (OS) One Inch and 1:50,000 maps of the area, yet it is unrecorded, so far as I know, until its appearance on the First Edition Six Inch OS map of 1867. In the absence of early spellings one would normally be inclined to leave the name well alone, a practice followed, intentionally or not, by the editors of the English Place-Name Society survey of Cumberland.2 However, to speakers or readers of Welsh the name is fairly transparent. -

The Lake District Atlantis What Lies Beneath Haweswater Reservoir?

http://www.discoveringbritain.org/connectors/system/phpthumb.php?src=co- ntent%2Fdiscoveringbritain%2Fimages%2FNess+Point+viewpoint%2FNess+- Point+test+thumbnail.jpg&w=100&h=80&f=png&q=90&far=1&HTTP_MODAUTH- =modx562284b1ecf2c4.82596133_2573b1626b27792.46804285&wctx=mgr&source=1 Viewpoint The Lake District Atlantis Time: 15 mins Region: North West England Landscape: rural Location: Bowderthwaite Bridge, Mardale, nearest postcode CA10 2RP Grid reference: NY 46793 11781 Keep and eye out for: Evidence of glaciation revealed in the smoothness of some of the boulders and rocks lying around the water’s edge Visitors to Haweswater receive little indication of the history of this remote valley. Like many of the other valleys in the Lake District, we might assume it is purely of volcanic and glacial origin, which indeed it is. But a quick glance at the map tells us that rather than being a natural lake we are looking at a reservoir. The passage of time has softened the shoreline of the lake to the extent that it now appears perfectly natural. However, when the water level is low little clues to the past may emerge... What lies beneath Haweswater reservoir? When the water level is low the tops of old stone walls stick out of the water like the scales of crocodiles basking in the sun. The stone walls are in fact the remnants of a lost village. The valley used to have a small hamlet at its head – Mardale Green – but this was submerged in the late 1930s when the water level of the valley’s original lake was raised to form a reservoir. -

Axe Working Sites on Path Renewal Schemes, Central Lake District

AXE WORKING SITES ON PATH RENEWAL SCHEMES, CENTRAL LAKE DISTRICT CUMBRIA Archaeological Survey Report Oxford Archaeology North June 2009 The National Trust and Lake District National Park Authority Issue No 2008-2009/903 OAN Job No:L10032 NGR: NY 21390 07921 NY 21891 08551 NY 27514 02410 NY 23676 08230 NY 36361 11654 (all centred) Axe Working Sites on Path Renewal Schemes, Cumbria: Archaeological Survey Report 1 CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................ 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................ 3 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Circumstances of the Project......................................................................... 4 1.2 Objectives..................................................................................................... 4 2. METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Project Design .............................................................................................. 6 2.2 The Survey ................................................................................................... 6 2.4 Archive......................................................................................................... 7 3. TOPOGRAPHIC AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................ 8 -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D.