What Do Bihar's Voters Want?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

Dalit Factor in Bihar's Politics

7. The (Maha) Dalit Factor in Bihar’s Politics Shreyas Sardesai* Until the 2010 election for the Bihar Assembly, elections in the state were largely analysed in terms of a six caste categories – Upper castes, Yadavs, other OBCs, Pasis, other Dalits and Muslims. Since 2007 however, Bihar politics has witnessed new developments and the caste dimension of elections cannot be fully understood without taking into account two additional caste categories, namely EBCs or Extremely Backward Classes, and Mahadalits. This chapter seeks to analyse the emergence of latter and its implications. In August 2007, the Nitish Kumar led JDU-BJP government set up the Bihar State Mahadalit Commission to “identify the castes within Scheduled Castes who lagged behind in the development process” and to “study [their] educational and social status and suggest measures for [their] upliftment”. In April 2008, 18 Dalit castes were brought under the Mahadalit category to begin with. These are Bantar, Bauri, Bhogta, Bhuiya, Chaupal, Dabgar, Dom/Dhangad, Ghasi, Halalkhor, Hari/Mehtar/Bhangi, Kanjar, Kurariar, Lalbegi, Musahar, Nat, Pan/Swasi, Rajwar and Turi. Three months later Dhobi and Pasi castes were also added to the Mahadalit category based on the Commission’s recommendation and then Chamars were also included in the Mahadalit category by the state government in November 2009 on the grounds that they too were lagging in literacy and economic status and were victims of untouchability at the hands of other Mahadalit castes1. The only sub-caste that was left out was Paswan or Dusadh *Author is Research Associate at Lokniti, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. -

Brief Industrial Profile of ARWAL District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of ARWAL District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Patliputra Industrial Estate, Patna-13 Phone:- 0612-2262719, 2262208, 2263211 Fax: 0612-2262186 e-mail: [email protected] Web- www.msmedipatna.gov.in 1 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 4 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2. District at a glance 4 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District -------- 7 3. Industrial Scenario Of --------- 8 3.1 Industry at a Glance 8 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 8 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In The 9 District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 10 3.5 Major Exportable Item 10 3.6 Growth Trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 10 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 10 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 10 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 10 3.9 Service Enterprises 10 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 11 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 11 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 11 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 11 4.1.2 Service Sector 11 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 11 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 11 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 12 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Arwal District 1. -

Identity, Dignity and Development As Trajectory: Bihar As a Model for Democratic Progress in Nepal? Part I

Commonwealth & Comparative Politics ISSN: 1466-2043 (Print) 1743-9094 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fccp20 Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar's experience Harry Blair To cite this article: Harry Blair (2018) Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar's experience, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 56:1, 103-123, DOI: 10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 Published online: 27 Dec 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 19 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fccp20 COMMONWEALTH & COMPARATIVE POLITICS, 2018 VOL. 56, NO. 1, 103–123 https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar’s experience Harry Blair South Asian Studies Council, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA ABSTRACT Down into the last decades of the twentieth century, Bihar remained India’s poorest state and one under the domination of its landowning upper castes – a well-nigh hopeless case for development in the view of most outside observers. But in the 1990s, a fresh leader gained a new dignity for the Backward castes, even as the state’s poverty and corruption continued unabated. And then in the mid-2000s, another Backward leader was able to combine this societal uplift with a remarkable level of economic development. -

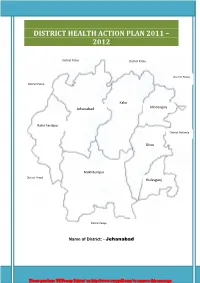

District Health Action Plan 2011 – 2012

DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN 2011 – 2012 District Patna District Patna District Patna District Patna Kako Modanganj Jehanabad Ratni Faridpur District Nalanda Ghosi Makhdumpur District Arwal Hulasganj District Gaya Name of District: - Jehanabad Please purchase 'PDFcamp Printer' on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this message. Acknowledgements This District Health Action plan prepared Under a Short & Hard Process of about survey of one month and this was a good Opportunity to revisit the situation of health services status and national programmes in district as well as to have a positive dialogue with departments like Public Health Engineering, Women and Child Development, Maternal and Child Health care etc. This document is an outcome of a collective effort by a number of individuals, related to our institutions and programmes:- Smt. Palka Shahni ,Chairperson of District Health Society, Jehanabad was a source of inspiration towards this effort vide her inputs to this process during D.H.S review meetings. Dr.Arvind kumar (A.C.M.O) Nodal officer for this action plan who always supported this endeavor through his guiding words and language. Mr. Nimish Manan , District Programme Manager was in incharge for the development of the DHAP(2011-12) . Mr Ravi Shankar Kumar , Distirct Planning Coordinator has given full time effort in developing DHAP(2011-12). Mr. Kaushal Kumar Jha, District Account Manager has put huge effort in financial Planning. Mr. Arvind Kumar, M&E Officer is the technical advisor for the data introduced inside this DISTRICT HEALTH ACTION PLAN. Mr. Manish Mani & Sefali from PHRN have given huge support. All district level Programme officer for various Health Programmes, B.H.Ms, M.O.I .Cs, PHCs, Field Office Staff have supported with their full participations, cooperation and learning spirit through out this process. -

Political Parties Worksheet- 1

POLITICAL PARTIES WORKSHEET- 1 QN QUESTION MA RK S 01 01 Which is not the component of a political party? (a) The leaders (b) The followers (c) The active members (d) The ministers 02 The clearly visible institutions of a democracy are: 01 (a) people (b) societies (c) political parties (d) pressure groups 03 Which is not a function of political party? 01 (a) To contest election (b) Faith in violent methods (c) Political education to the people (d) Form public opinion 04 Without the political parties, the utility of the government will remain: 01 (a) uncertain (b) powerful (c) peaceful (d) none of the above 05 .......... is an organised group of person who come together to contest election and try 01 to hold power in government. (a) Political party (b) Democracy (c) Parliament (d) None of these 06 Political parties can be reformed by 01 (a) reducing the role of muscle power (b) reducing the role of money (c) state funding of election (d) All of the above 07 The political parties of a country have a fundamental political in a society. 01 (a) choice (b) division (c) support (d) power 08 Political parties are there in a country to give people: 01 (a) freedom (b) choice (c) protection (d) none of the above Members of ruling party follows the directions of: (b) people (b) party leaders (c) pressure groups (d) None of the above 09 Which of the following is a regional party? 01 (a) Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) (b) Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) (c) Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) (d) Communist Party of India (Marxist) CPI 10 Name the party that emerged out of mass movement. -

Failure of the Mahagathbandhan

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Failure of the Mahagathbandhan In the Lok Sabha elections of 2019 in Uttar Pradesh, the contest was keenly watched as the alliance of the Samajwadi Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, and Rashtriya Lok Dal took on the challenge against the domination of the Bharatiya Janata Party. What contributed to the continued good performance of the BJP and the inability of the alliance to assert its presence is the focus of analysis here. In the last decade, politics in Uttar Pradesh (UP) has seen radical shifts. The Lok Sabha elections 2009 saw the Congress’s comeback in UP. It gained votes in all subregions of UP and also registered a sizeable increase in vote share among all social groups. The 2012 assembly elections gave a big victory to the Samajwadi Party (SP) when it was able to get votes beyond its traditional voters: Muslims and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The 2014 Lok Sabha elections saw the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) winning 73 seats with its ally Apna Dal. It was facilitated by the consolidation of voters cutting across caste and class, in favour of the party. Riding on the popularity of Narendra Modi, the BJP was able to trounce the regional parties and emerge victorious in the 2017 assembly elections as well. But, against the backdrop of anti-incumbency, an indifferent economic record, and with the coming together of the regional parties, it was generally believed that the BJP would not be able to replicate its success in 2019. However, the BJP’s performance in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections shows its continued domination over the politics of UP. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations

Election Commission of India- State Election, 2008 to the Legislative Assembly Of Rajasthan LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES - OTHER STATES 7 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 8 . CPI(ML)(L) Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) (Liberation) 9 . INLD Indian National Lok Dal 10 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 11 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 12 . RLD Rashtriya Lok Dal 13 . SHS Shivsena 14 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 15 . ABCD(A) Akhil Bharatiya Congress Dal (Ambedkar) 16 . ABHM Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha 17 . ASP Ambedkar Samaj Party 18 . BHBP Bharatiya Bahujan Party 19 . BJSH Bharatiya Jan Shakti 20 . BRSP Bharatiya Rashtravadi Samanta Party 21 . BRVP Bhartiya Vikas Party 22 . BVVP Buddhiviveki Vikas Party 23 . DBSP Democratic Bharatiya Samaj Party 24 . DKD Dalit Kranti Dal 25 . DND Dharam Nirpeksh Dal 26 . FCI Federal Congress of India 27 . IJP Indian Justice Party 28 . IPC Indian People¿S Congress 29 . JGP Jago Party 30 . LJP Lok Jan Shakti Party 31 . LKPT Lok Paritran 32 . LSWP Loktantrik Samajwadi Party 33 . NLHP National Lokhind Party 34 . NPSF Nationalist People's Front ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS - INDIA (Rajasthan ), 2008 LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 35 . RDSD Rajasthan Dev Sena Dal 36 . RGD Rashtriya Garib Dal 37 . RJVP Rajasthan Vikas Party 38 . RKSP Rashtriya Krantikari Samajwadi Party 39 . RSD Rashtriya Sawarn Dal 40 . -

Hon'ble Chief Minister of Bihar-Shri Nitish Kumar

Hon'ble Chief Minister of Bihar-Shri Nitish Kumar Profile: Tel: 2215601, 2217289 Fax- +91-612- 2224129 Email : [email protected] Fathers' Name : Late Kaviraj Ram Lakhan Singh Mother's Name : Late Parmeshwari Devi Date of Birth : 1st March, 1951 Place of Birth : Bakhtiarpur, District - Patna, State - Bihar. Marital Status : Married Date of Marriage : 22nd February, 1973. Spouse's Name : Late Manju Kumari Sinha. No. of Children : One. Educational Qualification : B.Sc. (Engineering) Educated at Bihar College of Engineering, Patna, Bihar. Profession : Political & Social worker, Agriculturist, Engineer. Permanent Address : Village - Hakikatpur , PO - Bakhtiarpur , District -Patna, Bihar Present Address : Patna, Bihar. Positions Held 1985-89 : Member, Bihar Legislative Assembly. 1986-87 : Member, Committee on Petitions, Bihar Legislative Assembly 1987-88 : President, Yuva Lok Dal, Bihar. 1987-89 : Member, Committee on Public Undertakings, Bihar Legislative Assembly 1989 : Secretary - General, Janata Dal, Bihar 1989 : Elected to 9th Lok Sabha. 1989-16/07/1990 : Member, House Committee (Resigned). 04/1990-11/1990 : Union Minister of State, Agriculture and Co-operation. 1991 : Re - elected to 10th Lok Sabha (2nd term). 1991-93 : General - Secretary, Janata Dal, Dy Leader of Janta Dal in Parliament 17/12/91-10/5/96 : Member, Railway Convention Committee. 8/4/93-10/5/96 : Chairman, Committee on Agriculture. 1996 : Re- elected to 11th Lok Sabha (3rd term) Member. Committee on Estimates. Member, General Purposes Committee. Member, Joint Committee on the Constitution (Eighty-first Amendment Bill, 1996). 1996-98 : Member, Committee on Defence. 1998 : Re- elected to 12th Lok Sabha (4th term) 19/3/98-5/8/99 : Union Cabinet Minister, Railways. -

Organization Profile

SANKALP JYOTI ORGANIZATION PROFILE Vision : To have healthy and self reliant society where equal opportunities are made available to the disadvantaged with special reference to women. Mission : To create a self reliant society of disadvantaged & marginalized groups who can avail equal opportunities in which woman play proactive role. Goal : Sustainable development of the society through women empowerment. Activities of the organization:- 1. We are actively participating in Mission Indradhanush(MI) program on Immunization in Bihar along with the support of BVHA, Alliance for Immunization in India & GAVI. 2. With the support of BVHA & KKS we conducted Skill Development Training Program on Beautician, Electrician, Masonry, Cycle-Motor repairing at 12 villages of Maner block in Patna districts of Bihar. 3. With the support of Agriculture department of GoB, We are mobilizing & mapping the farmers to develop the Bio-Gas plant in Patna, Gaya,Vaishali, Muzafarpur & Darbhanga district of Bihar. 4. Organized one day workshop on Bihar Baal Ghoshnapatra- Children Manifesto on the occasion of Bihar Legislative Assembly- 2015 with issues of Child, Health & Nutrition with the support of World Vision-Bihar in Kishanganj district 5. With the support of Dan Church Aid & IDF we procured the 7500 kg. SEED of rice to distribute among the dalit communities of Katra & Sonepur panchayat of Katra Block in Muzaffarpur district. 6. We are conducting Skill Development Training program on ICT, Yoga, Mass-communication, Soft Skill, Tailoring, Beauty Advisor under MES scheme of DGET in Patna district with the support of Ministry of Labour & employment Department, GOI. SANKALP JYOTI 7. We had translated the training material from English to Hindi on Emotional Resilience & Health under the Girls First project for the U.S.