Identity, Dignity and Development As Trajectory: Bihar As a Model for Democratic Progress in Nepal? Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

Bihar's Exposure to Innovative Governance Practices

Bihar’s Exposure To Innovative Governance Practices A REPORT OF THE SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI OCTOBER, 2007 FINAL DRAFT BIHAR’S EXPOSURE TO INNOVATIVE GOVERNANCE PRACTICES A REPORT OF THE SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI OCTOBER, 2007 SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR 1. Dr. Satish C. Jha - Chairman 2. Shri Saurabh Srivastava - Member 3. Late Shri Rajender Singh - Member 4. Shri R.K. Sinha - Member 5. Dr. P.V. Dehadrai - Member 6. Dr. Nachiket Mor - Member 7. Shri Tarun Das - Member 8. Shri Deepak Dasgupta - Member 9. Prof. Pradip N. Khandwalla - Member 10. Prof. C. P. Sinha - Member 11. Chief Secretary, Government of Bihar - Member 12. Resident Commissioner, Government of Bihar - Member iv Bihar’s Exposure to Innovative Governance Practices — A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report is based on extensive survey of literature and analysis on issues of governance carried out by Special Task Force Member, Prof. Pradip N. Khandwalla (Ex-Director of IIM, Ahmedabad). He was assisted by Task Force Research Consultants Gordhan Saini and Sudhir Suthar. Prof. Khandwalla received support from Pravin Lahiri, Ex-Chief Secretary of Gujarat and Anita Karwal, IAS, on information/data related to a Gujarat innovation. He also received information access from Prof. Gopal Naik (of IIM, Bangalore), and comments of Hasmukh Adhia, IAS, former Principal Secretary to Chief Minister of Gujarat. The Task Force received valuable information and comments from the Government of Bihar and Kamla Prasad (Ex-Chief Secretary of Bihar). The other Task Force Members provided valuable comments. -

S. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; B. June 5, 1937; M. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 D.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986

M MADDANNA, SHRI M. : Studied upto B.A.; Congress (I) (Karnataka); s. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; b. June 5, 1937; m. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 d.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986. Per. Add. : 5, III Cross, Annayappa Block, Kumara Park West, Bangalore (Karnataka). MADHAVAN, SHRI K. K. : B.A., LL.B.; Congress (U) (Kerala); s. of Shri Kunhan; b. July 23, 1917; m. Shrimati Devi, 1 s. and 1 d.; Member, (i) Kerala Legislative Assembly, 1965 and (ii) Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1976 to 2-4-1982; Died. Obit. on 21-10-1999. MADHAVAN, SHRI S. : B.Com., B.L.; A.I.A.D.M.K. (Tamil Nadu); s .of Shri Selliah Pillai; b . October 3, 1933; m. Shrimati Dhanalakshmi, 1 s. and 2 d.; Member, Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly, 1962-76 and 1984-87; Minister, Government of Tamil Nadu, 1967-76; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1990 to 2-4- 1996. Per. Add. : 17, Sixth Main Road, Raja Annamalai Puram, Madras (Tamil Nadu). MADNI, SHRI MAULANA ASAD : Fazil (equivalent to M.A. in Islamic Theology); Congress (I) (Uttar Pradesh); s. of Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni; b. 1928; m. Shrimati Barirah Bano, 4 s. and 2 d.; Vice-President, U.P.C.C.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1968 to 2-4-1974, 5-7-1980 to 4-7-1986 and 3-4-1988 to 2-4-1994. Per. Add . : Madani Manzil , Deoband , District Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh). MAHABIR PRASAD, DR. : M.A., Ph.D.; Janata Party (Bihar); s. of Shri Sahdev Yadav; b. 1939; m. Shrimati Chandra Kala Devi, 2 s. -

Conference Agenda

CONFERENCE AGENDA 8:30 AM: Participant Registration and Coffee 9:00 AM Welcome and Introductions Iqbal Dhaliwal, Director of Policy, J-PAL Global, M.I.T. Gyanendra Badgaiyan, Director of J-PAL South Asia at IFMR, Chennai 9:30 AM HEALTH - Full Immunization, Fortification & Provider Attendance Rachel Glennerster, Executive Director, J-PAL, M.I.T. Neelima Khetan, CEO, Seva Mandir, Udaipur, Rajasthan 10:15 AM HEALTH - Improving Health and Increasing School Attendance via Deworming Karthik Muralidharan, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of California - San Diego L.V. Subramanyam, I.A.S., Principal Secretary-Health, Government of Andhra Pradesh 10:45 AM Coffee break 11:00 AM Inauguration and Key Findings Honorable Nitish Kumar, Chief Minister of Bihar Abhijit Banerjee, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. 12:00 PM GOVERNANCE - Voters' Campaign Rohini Pande, Professor of Economics, Harvard University Anjali Bhardwaj, Founding Member and Director, Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Delhi 12:45 PM Lunch break 1:45 PM PANEL DISCUSSION - Partnerships for Bihar’s Development Keynote Speaker: Honorable Sushil Kumar Modi, Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar Honorable N.K. Singh, Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) from Bihar Navin Kumar, I.A.S., Development Commissioner, Government of Bihar Bhanu Pratap Sharma, I.A.S., Principal Secretary of Finance, Government of Bihar Michael Anderson, Head of the India Program, UK Department for International Development Roberto Zagha, World Bank Country Director for India Abhijit Banerjee, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. Robin Burgess, Professor of Economics, London School of Economics 3:00 PM GOVERNANCE - Improving Police Effectiveness in Rajasthan Esther Duflo, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. -

India: the Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India

ASARC Working Paper 2009/06 India: The Weakening of the Congress Stranglehold and the Productivity Shift in India Desh Gupta, University of Canberra Abstract This paper explains the complex of factors in the weakening of the Congress Party from the height of its power at the centre in 1984. They are connected with the rise of state and regional-based parties, the greater acceptability of BJP as an alternative in some of the states and at the Centre, and as a partner to some of the state-based parties, which are in competition with Congress. In addition, it demonstrates that even as the dominance of Congress has diminished, there have been substantial improvements in the economic performance and primary education enrolment. It is argued that V.P. Singh played an important role both in the diminishing of the Congress Party and in India’s improved economic performance. Competition between BJP and Congress has led to increased focus on improved governance. Congress improved its position in the 2009 Parliamentary elections and the reasons for this are briefly covered. But this does not guarantee an improved performance in the future. Whatever the outcomes of the future elections, India’s reforms are likely to continue and India’s economic future remains bright. Increased political contestability has increased focus on governance by Congress, BJP and even state-based and regional parties. This should ensure improved economic and outcomes and implementation of policies. JEL Classifications: O5, N4, M2, H6 Keywords: Indian Elections, Congress Party's Performance, Governance, Nutrition, Economic Efficiency, Productivity, Economic Reforms, Fiscal Consolidation Contact: [email protected] 1. -

RAJYA SABHA ______∗SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Wednesday, August 24, 2011/ Bhadrapada 2, 1933 (Saka) ______

RAJYA SABHA _________ ∗SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _________ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _________ Wednesday, August 24, 2011/ Bhadrapada 2, 1933 (Saka) _________ OBITUARY REFERENCE MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I refer with profound sorrow to the passing away of Shri Rafique Alam, a former Member of this House on the 3rd of April, 2011 at the age of 82 years. Born at Kashibari in Purnea, Bihar in June, 1929, Shri Rafique Alam had his education at Russel High School, Kishanganj High School, Purnea, and Aligarh Muslim University. An agriculturist, Shri Rafique Alam was associated with several educational institutions in Purnea district of Bihar. Shri Rafique Alam was the recipient of the National Integration Award, 1988. Shri Alam began his legislative career as a Member of the Bihar Legislative Assembly in 1962 and was a Member of that Assembly from 1962 to 1967 and again from 1969 to 1980. He served as Cabinet Minister in the Government of Bihar for several terms, holding portfolios of Transport, Local Self-Government, Irrigation, Housing, Jails, Animal Husbandry, Fishery and Wakf, PWD, Rural Reconstruction and Panchayati Raj. Shri Rafique Alam represented the State of Bihar in this House from April, 1982 to April, 1988, and again from April, 1988 to ___________________________________________________ ∗This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. 206 April, 1994. Shri Rafique Alam also served as Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas from February to June, 1988; as Minister of State in the Ministry of Textiles from 1988 to 1989, and as Minister of State (Independent Charge) in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare from July to November, 1989 in the Union Council of Ministers. -

U.S. Ambassador to China Terry Branstad

U.S. Ambassador to China Terry Branstad On December 7, 2016, Governor Branstad announced that he had accepted the nomination from President-elect Donald Trump to serve as Ambassador of the United States to the People’s Republic of China. He was confirmed by the Senate on May 22, 2017, and was sworn in on May 24, 2017. Ambassador Terry Branstad was born, raised and educated in Iowa. A native of Leland, Branstad was elected to the Iowa House in 1972, ’74 and ’76, and elected as Iowa’s lieutenant governor in 1978. Branstad was Iowa’s longest-serving governor, from 1983 to 1999. As the state’s chief executive, he weathered some of Iowa’s worst economic turmoil, during the farm crisis of the ‘80s, while helping lead the state’s resurgence to a booming economy in the ‘90s. At the end of his tenure, Iowa enjoyed record employment, an unprecedented $900 million budget surplus, and the enactment of historic government overhauls that led to greater efficiencies in state government. As a result of Governor Branstad’s hands-on, round-the-clock approach to economic development, Iowa’s unemployment rate went from 8.5 percent when he took office to a record low 2.5 percent by the time he left in 1999. Following his four terms as governor, Branstad served as president of Des Moines University (DMU). During his 6-year tenure, he was able to grow the university into a world-class educational facility. Its graduates offer health care in all 50 states and in nearly every Iowa county. -

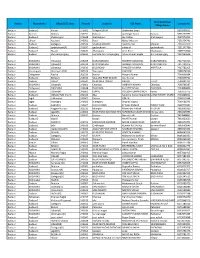

Zila Parishad JITESH KUMAR ARARIA

Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad JITESH KUMAR 2 Araria RAJ KUMAR RAJ KRIPA NAND JHA 9835838537 3 Bhargama MD. SARWAR ALAM MD. SIRAJUDDIN 9709996217 4 Forbesganj SANJAY KUMAR SAH MAHENDRA SAH 9199120088 5 Jokihat MD. ASHALAM JAFAR HAZI ASFAQUE HUSAIN 9308734215 ARARIA 6 Kursakatta SANTOSH KUMAR SAH MAKSHUDAN SAH 7 Narpatganj MANOJ KR. BHARATI BHAGWAN MANDAL 9709573281 8 Palasi 9 Raniganj ANUBHAV KUMAR JAI PRAKASH NAYAK 9570357990 10 Sikti PREM KUMAR PASWAN YOGENDRA PASWAN 7250394187 D:\Sarvesh-2012\IT Operators Deployed in District HQ Block\IT Operators deployed in the districts_HQ_Block 1 | 38 it operator_Blocks_n_HQ_280 (2) Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad SANTOSH KUMAR 9771734044 2 Arwal ARVIND KUMAR BHIM SINGH 9334480335 3 Kaler AMITSH SHRIVASTAV VIJAY KUMAR SHRIVASTAV ARWAL 4 Karapi RAVIRANJAN KR. PARASAR HARIDWAR SHARMA 8334800422 5 Kurtha KUNDAN KUMAR BINESHWAR PANDIT 9279386443 6 Sonabhadra Vanshi Suryapur MANOJ KUMAR LEELA SINGH D:\Sarvesh-2012\IT Operators Deployed in District HQ Block\IT Operators deployed in the districts_HQ_Block 2 | 38 it operator_Blocks_n_HQ_280 (2) Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad RAKESH -

RJD Eyes Mumbai, to Consolidate Political Strength and Expand Base in Maharashtra by : INVC Team Published on : 19 Dec, 2017 08:04 PM IST

RJD eyes Mumbai, to consolidate political strength and expand base in Maharashtra By : INVC Team Published On : 19 Dec, 2017 08:04 PM IST INVC NEWS Mumbai, Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) has geared its resources and is all set to flex its political muscle in Mumbai. The party has also drawn a strategy to field candidates for contesting maximum number of seats in civic polls, assembly elections and the general elections in Maharashtra even as it looks confident to consolidate its political strength and expand its base across the state. “We are committed to improving Mumbai’s rapidly creaking infrastructure and providing a sustained roadmap to the city’s economic development. It is our sincere belief that prudent economic policies and administrative initiatives need to be rolled out to restore the vibrancy of the city. RJD has the capabilities and is fully ready to gain the requisite public mandate to restore the bustling megapolis to its former glory and strengthen its efficacies as the financial capital of the country. The party is also fully committed to the sustained growth and development of Maharashtra.” stated Ayub Hungund, RJD President, Mumbai. RJD followers and party workers had gathered in huge numbers to felicitate Mumbai Party President Ayub Hungund. The impressive gathering of the party cadre was seen as a show of strength for the party in a politically important constituency like Mumbai. Following its consolidation in Mumbai, the party has also planned a mass outreach across Maharashtra to spread its appeal to the population in the state. The party will be placing emphasis on core issues which have severely affected the growth and development of the state and try to address them in a proactive manner. -

4 Patrimonial and Programmatic Talking About Democracy in a South Indian Village

4 Patrimonial and Programmatic Talking about Democracy in a South Indian Village PAMELA PRICE AND DUSI SRINIVAS How do people in India participate politically, as citizens, clients and/or subjects?1 This query appears in various forms in ongoing debates concerning the extent and nature of civil society, the pitfalls of patronage democracy, and the role of illegal- ity in political practice, to name a few of the several concerns about political spheres in India. A focus for discussion has been the relationship of civil society institutions (with associated principles of equality and fairness) to political spheres driven mainly by political parties and to what Partha Chatterjee desig- nated as ‘political society’.2 Since 2005, with the publication of the monograph, Seeing the State: Governance and Governmentality in India (Corbridge et al.), there is growing support for the argument that political cultures and practices in India, from place to place and time to time, to greater and lesser degrees, include 1. Thanks to those who commented on earlier drafts of this piece when it was presented at the Department of Political Science at the University of Hyderabad, the South Asia Symposium in Oslo, and at the workshop ‘Practices and Experiences of Democracy in Post-colonial Locali- ties’, part of the conference, ‘Democracy as Idea and Practice’ organized by the University of Oslo. We are grateful to K.C. Suri for suggesting the term ‘programmatic’ in our discussions of the findings here. Thanks to the editors of this volume, David Gilmartin and Sten Widmalm for reading and commenting on this piece. -

Bareilly Zone CSC List

S Grampanchayat N District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name o Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 Badaun Ujhani Nausera 243601 Rural Mukul Maurya 7351054741 Badaun Budaun Dataganj 243631 VILLEGE MARORI Ajeet Kumar Marauri 7351070370 Badaun Budaun2 qadarchowk(R) 243637 qadarchowk sifate ali qadarchowk 7351147786 Badaun Budaun1 Bisauli 243632 dhanupura Amir Khan Dhanupura 7409212060 Badaun Budaun shri narayanganj 243639 mohalla shri narayanganj Ashok Kumar Gupta shri narayanganj 7417290516 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 NARAYANGANJ SHOBHIT AGRAWAL NARAYANGANJ 7417721016 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(U) 243639 BILSI ROAD PRADEEP MISHRA AHIRTOLA 7417782205 Badaun Vazeerganj Wazirganj (NP) 202526 Wazirganj YASH PAL 7499478130 Badaun Dahgawan Nadha 202523 Nadha Mayank Kumar 7500006864 Badaun Budaun2 Bichpuri 243631 VILL AND POST MIAUN Atul Kumar 7500379752 Badaun Budaun Ushait 243641 NEAR IDEA TOWER DHRUV Ushait 7500401211 Badaun BUDAUN1 Ujhani(R) 243601 Chandau AMBRISH KUMAR Chandau 7500766387 Badaun Dahgawan DANDARA 243638 DANDARA KULDEEP SINGH DANDARA 7534890000 Badaun Budaun Ujhani(R) 243601 KURAU YOGESH KUMAR SINGH Kurau 7535079775 Badaun Budaun2 Udhaiti Patti Sharki 202524 Bilsi Sandeep Kumar ShankhdharUGHAITI PATTI SHARKI 7535868001 -

I'8cj.I8sl the G9vemment to Lat [Translation) This August House Know the Steps It Is Going to Take to Solve Water Crisis in Deihl

403 WlttenAnstNtS APRIL 10,1992 WritrenAnswers 404 would Ike to I'8CJ.I8Sl the G9vemment to lat [Translation) this august House know the steps It Is going to take to solve water crisis in Deihl. This Is SHRI BRISHIAN PATEL: He has been not the problem merely In those areas where arrested. Arrests have been made. They the hon. Mermers of Par1Iament or the Min- hav~ been nabbed. * is related to the leader isters live, but for the common man who face of the opposition in Bihar, Dr Jagannath the water problem. The Goveml'l'J8nt should Mishra. Because thls is a case of political take some concrete steps to supply them vendena. Shri J)e.vendra Prasad Yadav's water and make a statement in the younger brother was killed deliberately. It is House ..•..• ( Int8fl1Jptions). because Shri Lalu Prasad Yadav was about to inaugurate the Phulparas Sub-division. SHRI KALKA' tiAs (KaroIbagh): Mr. Those people did not want it and resented It. Speaker, SIr, we have drawn the attention of They thought that because of initiative being the House towards this many times. This Is taken by Janata Dal Phulparas has been the factual position that Delhi is going to face made a sub division and later this credit will acute water crisis, as stated by the hon. go to them only. That is why quite deliber- Member. This has created a lot of tension In ately a conspiracy was hatched and hon. the minds of people. W. have been drawing Member, Shri Devendra Prasad Yadav's the attention of the administration for many youngerbrotherwas killed.