Bihar Towards a Development Strategy Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bihar's Exposure to Innovative Governance Practices

Bihar’s Exposure To Innovative Governance Practices A REPORT OF THE SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI OCTOBER, 2007 FINAL DRAFT BIHAR’S EXPOSURE TO INNOVATIVE GOVERNANCE PRACTICES A REPORT OF THE SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI OCTOBER, 2007 SPECIAL TASK FORCE ON BIHAR 1. Dr. Satish C. Jha - Chairman 2. Shri Saurabh Srivastava - Member 3. Late Shri Rajender Singh - Member 4. Shri R.K. Sinha - Member 5. Dr. P.V. Dehadrai - Member 6. Dr. Nachiket Mor - Member 7. Shri Tarun Das - Member 8. Shri Deepak Dasgupta - Member 9. Prof. Pradip N. Khandwalla - Member 10. Prof. C. P. Sinha - Member 11. Chief Secretary, Government of Bihar - Member 12. Resident Commissioner, Government of Bihar - Member iv Bihar’s Exposure to Innovative Governance Practices — A Report of the Special Task Force on Bihar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report is based on extensive survey of literature and analysis on issues of governance carried out by Special Task Force Member, Prof. Pradip N. Khandwalla (Ex-Director of IIM, Ahmedabad). He was assisted by Task Force Research Consultants Gordhan Saini and Sudhir Suthar. Prof. Khandwalla received support from Pravin Lahiri, Ex-Chief Secretary of Gujarat and Anita Karwal, IAS, on information/data related to a Gujarat innovation. He also received information access from Prof. Gopal Naik (of IIM, Bangalore), and comments of Hasmukh Adhia, IAS, former Principal Secretary to Chief Minister of Gujarat. The Task Force received valuable information and comments from the Government of Bihar and Kamla Prasad (Ex-Chief Secretary of Bihar). The other Task Force Members provided valuable comments. -

Identity, Dignity and Development As Trajectory: Bihar As a Model for Democratic Progress in Nepal? Part I

Commonwealth & Comparative Politics ISSN: 1466-2043 (Print) 1743-9094 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fccp20 Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar's experience Harry Blair To cite this article: Harry Blair (2018) Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar's experience, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 56:1, 103-123, DOI: 10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 Published online: 27 Dec 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 19 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fccp20 COMMONWEALTH & COMPARATIVE POLITICS, 2018 VOL. 56, NO. 1, 103–123 https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2018.1411231 Identity, dignity and development as trajectory: Bihar as a model for democratic progress in Nepal? Part I. Bihar’s experience Harry Blair South Asian Studies Council, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA ABSTRACT Down into the last decades of the twentieth century, Bihar remained India’s poorest state and one under the domination of its landowning upper castes – a well-nigh hopeless case for development in the view of most outside observers. But in the 1990s, a fresh leader gained a new dignity for the Backward castes, even as the state’s poverty and corruption continued unabated. And then in the mid-2000s, another Backward leader was able to combine this societal uplift with a remarkable level of economic development. -

S. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; B. June 5, 1937; M. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 D.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986

M MADDANNA, SHRI M. : Studied upto B.A.; Congress (I) (Karnataka); s. of Shri Mali Chikkapapanna; b. June 5, 1937; m. Shrimati Kenchamma, 1 d.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1980 to 2-4-1986. Per. Add. : 5, III Cross, Annayappa Block, Kumara Park West, Bangalore (Karnataka). MADHAVAN, SHRI K. K. : B.A., LL.B.; Congress (U) (Kerala); s. of Shri Kunhan; b. July 23, 1917; m. Shrimati Devi, 1 s. and 1 d.; Member, (i) Kerala Legislative Assembly, 1965 and (ii) Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1976 to 2-4-1982; Died. Obit. on 21-10-1999. MADHAVAN, SHRI S. : B.Com., B.L.; A.I.A.D.M.K. (Tamil Nadu); s .of Shri Selliah Pillai; b . October 3, 1933; m. Shrimati Dhanalakshmi, 1 s. and 2 d.; Member, Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly, 1962-76 and 1984-87; Minister, Government of Tamil Nadu, 1967-76; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1990 to 2-4- 1996. Per. Add. : 17, Sixth Main Road, Raja Annamalai Puram, Madras (Tamil Nadu). MADNI, SHRI MAULANA ASAD : Fazil (equivalent to M.A. in Islamic Theology); Congress (I) (Uttar Pradesh); s. of Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni; b. 1928; m. Shrimati Barirah Bano, 4 s. and 2 d.; Vice-President, U.P.C.C.; Member, Rajya Sabha, 3-4-1968 to 2-4-1974, 5-7-1980 to 4-7-1986 and 3-4-1988 to 2-4-1994. Per. Add . : Madani Manzil , Deoband , District Saharanpur (Uttar Pradesh). MAHABIR PRASAD, DR. : M.A., Ph.D.; Janata Party (Bihar); s. of Shri Sahdev Yadav; b. 1939; m. Shrimati Chandra Kala Devi, 2 s. -

Conference Agenda

CONFERENCE AGENDA 8:30 AM: Participant Registration and Coffee 9:00 AM Welcome and Introductions Iqbal Dhaliwal, Director of Policy, J-PAL Global, M.I.T. Gyanendra Badgaiyan, Director of J-PAL South Asia at IFMR, Chennai 9:30 AM HEALTH - Full Immunization, Fortification & Provider Attendance Rachel Glennerster, Executive Director, J-PAL, M.I.T. Neelima Khetan, CEO, Seva Mandir, Udaipur, Rajasthan 10:15 AM HEALTH - Improving Health and Increasing School Attendance via Deworming Karthik Muralidharan, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of California - San Diego L.V. Subramanyam, I.A.S., Principal Secretary-Health, Government of Andhra Pradesh 10:45 AM Coffee break 11:00 AM Inauguration and Key Findings Honorable Nitish Kumar, Chief Minister of Bihar Abhijit Banerjee, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. 12:00 PM GOVERNANCE - Voters' Campaign Rohini Pande, Professor of Economics, Harvard University Anjali Bhardwaj, Founding Member and Director, Satark Nagrik Sangathan, Delhi 12:45 PM Lunch break 1:45 PM PANEL DISCUSSION - Partnerships for Bihar’s Development Keynote Speaker: Honorable Sushil Kumar Modi, Deputy Chief Minister of Bihar Honorable N.K. Singh, Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) from Bihar Navin Kumar, I.A.S., Development Commissioner, Government of Bihar Bhanu Pratap Sharma, I.A.S., Principal Secretary of Finance, Government of Bihar Michael Anderson, Head of the India Program, UK Department for International Development Roberto Zagha, World Bank Country Director for India Abhijit Banerjee, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. Robin Burgess, Professor of Economics, London School of Economics 3:00 PM GOVERNANCE - Improving Police Effectiveness in Rajasthan Esther Duflo, Professor of Economics, M.I.T. -

Environment Impact Assessment and Socio Economic Studies

CHAPTER - IX ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND SOCIO ECONOMIC STUDIES 9.0 Objectives of the study The objective of environmental impact assessment and socio- economic studies is to identify the possible environmental and socio- economic effects due to the proposed Kosi-Mechi intrastate link project of Bihar and to suggest measures to mitigate or ameliorate the anticipated adverse impacts on the environment. The study was assigned to M/s Economic Development Trust (EDT), New Delhi. A brief account of the study is presented in this chapter. 9.1 The project proposal The Kosi-Mechi intrastate link project envisages diversion of 7,825 MCM of Kosi water from existing Hanuman Nagar Barrage on Indo-Nepal border to Mechi river (a tributary of Mahananda) about 1.5 km upstream of its confluence with Mahananda river in Makhanpur village of Kishanganj district of Bihar state. The proposed link canal offtakes from the left side (eastern side) of the barrage near Hanuman Nagar at FSL 74.371 m and outfalls into Mechi river at FSL 54.239 m. The total length of the link canal is 117.50 km. This link canal will cross number of streams/rivers, road and railway lines for which 9 canal syphons, 14 syphon aqueducts, 42 road bridges and 9 hume pipe culverts have been proposed. 28 head regulators, 10 cross regulators and 3 escapes have also been provided for the link canal regulation. 9.2 Project justification Bihar is India's most flood‐prone state, with about 76% of the population in north Bihar living under the recurring threat of flood devastation. -

RAJYA SABHA ______∗SYNOPSIS of DEBATE ______(Proceedings Other Than Questions and Answers) ______Wednesday, August 24, 2011/ Bhadrapada 2, 1933 (Saka) ______

RAJYA SABHA _________ ∗SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _________ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _________ Wednesday, August 24, 2011/ Bhadrapada 2, 1933 (Saka) _________ OBITUARY REFERENCE MR. CHAIRMAN: Hon. Members, I refer with profound sorrow to the passing away of Shri Rafique Alam, a former Member of this House on the 3rd of April, 2011 at the age of 82 years. Born at Kashibari in Purnea, Bihar in June, 1929, Shri Rafique Alam had his education at Russel High School, Kishanganj High School, Purnea, and Aligarh Muslim University. An agriculturist, Shri Rafique Alam was associated with several educational institutions in Purnea district of Bihar. Shri Rafique Alam was the recipient of the National Integration Award, 1988. Shri Alam began his legislative career as a Member of the Bihar Legislative Assembly in 1962 and was a Member of that Assembly from 1962 to 1967 and again from 1969 to 1980. He served as Cabinet Minister in the Government of Bihar for several terms, holding portfolios of Transport, Local Self-Government, Irrigation, Housing, Jails, Animal Husbandry, Fishery and Wakf, PWD, Rural Reconstruction and Panchayati Raj. Shri Rafique Alam represented the State of Bihar in this House from April, 1982 to April, 1988, and again from April, 1988 to ___________________________________________________ ∗This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. 206 April, 1994. Shri Rafique Alam also served as Deputy Minister in the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas from February to June, 1988; as Minister of State in the Ministry of Textiles from 1988 to 1989, and as Minister of State (Independent Charge) in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare from July to November, 1989 in the Union Council of Ministers. -

Kishanganj Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE KISHANGANJ INTRODUCTION Kishanganj district is one of the thirty-eight districts of Bihar. Kishanganj district is a part of Purnea division. Kishanganj is situated in the northeastern part of Bihar and is is part of the chicken neck on the map of India. Kishanganj has an international border with Nepal and a narrow strip of 20 km land of West Bengal separates Kishanganj district from Bangladesh. Kishanganj district is surrounded by the districts of Araria and Purnea of Bihar, districts of Uttar Dinajpur and Darjeeling of West Bengal and Nepal in the north. The important rivers flowing from the district are Mahananda, Kankai, Mechi, Doictnk, Ratua, Ramzan and Sudhani. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Kishanganj is the distortion of the name Krishna-Kunj. During the Mughal period, Kishanganj district was the part of Nepal and was known as Nepalgarh. Nepalgarh was captured during the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Alam and renamed as Alamganj in his honour. Khagara was made the administrative headquarters and the historical "Khagra Mela" is held here every year. During the Mughal rule under Nawab Mohammed Fakiruddin, a wandering Hindu saint refused to enter Amanganj despite being very tired because the names of the place, river and Nawab were Alamganj, Ramzan and Fakiruddin respectively. When the Nawab heard this grievance of the itinerant saint, he announced that some portion of land would be renamed as Krishna-Kunj. With passage of time, the name Krishna-Kunj got distorted to Kishanganj. Kishanganj was earlier an important sub-division of the erstwhile Purnea district and became an independent district on 14th January 1990. -

Zila Parishad JITESH KUMAR ARARIA

Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad JITESH KUMAR 2 Araria RAJ KUMAR RAJ KRIPA NAND JHA 9835838537 3 Bhargama MD. SARWAR ALAM MD. SIRAJUDDIN 9709996217 4 Forbesganj SANJAY KUMAR SAH MAHENDRA SAH 9199120088 5 Jokihat MD. ASHALAM JAFAR HAZI ASFAQUE HUSAIN 9308734215 ARARIA 6 Kursakatta SANTOSH KUMAR SAH MAKSHUDAN SAH 7 Narpatganj MANOJ KR. BHARATI BHAGWAN MANDAL 9709573281 8 Palasi 9 Raniganj ANUBHAV KUMAR JAI PRAKASH NAYAK 9570357990 10 Sikti PREM KUMAR PASWAN YOGENDRA PASWAN 7250394187 D:\Sarvesh-2012\IT Operators Deployed in District HQ Block\IT Operators deployed in the districts_HQ_Block 1 | 38 it operator_Blocks_n_HQ_280 (2) Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad SANTOSH KUMAR 9771734044 2 Arwal ARVIND KUMAR BHIM SINGH 9334480335 3 Kaler AMITSH SHRIVASTAV VIJAY KUMAR SHRIVASTAV ARWAL 4 Karapi RAVIRANJAN KR. PARASAR HARIDWAR SHARMA 8334800422 5 Kurtha KUNDAN KUMAR BINESHWAR PANDIT 9279386443 6 Sonabhadra Vanshi Suryapur MANOJ KUMAR LEELA SINGH D:\Sarvesh-2012\IT Operators Deployed in District HQ Block\IT Operators deployed in the districts_HQ_Block 2 | 38 it operator_Blocks_n_HQ_280 (2) Panchayati Raj Department Government of Bihar List of Panchayat IT Operators Deployed in the Districts for PRIASoft SL District Block Name Father's Name Mobile 1 Zila Parishad RAKESH -

TACR: India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 41127 March 2011 India: Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector Prepared by MMM Group, Canada Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada For Road Construction Department Government of Bihar This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Asian Development Bank Road Construction Department Government of Bihar FINAL REPORT ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector March 2011 (Updated May 2011) Milestone Report MMM Group, Canada Final Report, March 2011 ADB TA 7130-IND Institutional Strengthening of the Bihar Road Sector 3 Final Report, March 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Introduction and TA Timeline ........................................................................................ 7 1.2 Interim Report and Mid-term Workshop ........................................................................ 8 1.3 Need for Changes in TA Scope of Work ...................................................................... -

Access-Of-Muslims-And-Other-Religious-Minorities-To-Rights-And-Freedoms-Bihar.Pdf

Access of Muslims and Other Religious Minorities to Rights and Freedoms – Bihar This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for noncommercial purposes under the same original license terms. Some rights reserved Published by: Misaal - Centre for Equity Studies 24, Khazan Singh Building Adhchini, Aurobindo Marg New Delhi - 110 017, India Tel: +91 (0)11-26535961 / 62 Email: [email protected] Web : www.misaal.ngo Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/misaalfellowship Credits: This report has been produced with the assistance of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. Minority Rights Group International provided technical help. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Misaal-CES, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency or of Minority Rights Group International. December 2016 Access of Muslims and Other Religious Minorities to Rights and Freedoms Bihar December 2016 i Executive Summary 1. This study aims to examine the access of religious minorities in the state of Bihar to minority rights - including to freedom of religion, life and security, and social, economic and cultural rights. The focus of the study is Muslims - by far the largest religious minority in Bihar, and India as a whole. We try to measure access to rights by mapping poor Muslims’ conditions as well as by examining the quality of state provisioning for them. This examination is based on (i) primary data on micro evidence on the condition of poor Muslims, collected from 5 sample sites of Muslim habitations in UP (Patna, Vaishali, Sitamarhi, Darbhanga and Madhubani districts) using household surveys (sample of 100 poor Muslim households at each site) and interviews and focus group discussions, as methods. -

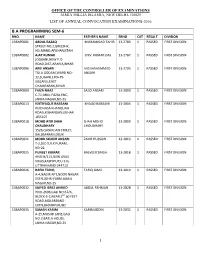

B.A Programming Sem-6

OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER OF EXAMINATIONS JAMIA MILLIA ISLAMIA, NEW DELHI-110025 LIST OF ANNUAL CONVOCATION EXAMINATIONS-2016 B.A PROGRAMMING SEM-6 RNO NAME FATHER'S NAME ERNO CAT RESULT DIVISION 13BAP0001 ABDUL RAZAQ MUHAMMAD TAHIR 13-2783 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION STREET NO.2,GREESHK, HELMAND,AFGHANISTAN 13BAP0002 AJAY KUMAR SHIV KUMAR DAS 13-2787 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION JOGBANI,NEW P.O ROAD,DIST-ARARIA,BIHAR 13BAP0006 ARIF ANSARI AAS MAHAMMAD 13-2795 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION TOLA GODAM,WARD NO- ANSARI 12,SUGANLI,PO+PS- SUGANLI,EAST CHAMPARAN,BIHAR 13BAP0009 FAIZA NAAZ SAJID ANSARI 13-2800 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION C-71,ABUL FAZAL ENC, JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 13BAP0013 ISHTIYAQUE RABBANI KHALID RABBANI 13-2804 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION RUIDHASA KHANQUAH ROAD,KISHANGANJ,BIHAR -855107 13BAP0018 MOHD ATIR SHAH SHAH MOHD 13-2809 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION CHAUDHARY CHOUDHARY 1526,QASIM JAN STREET, BALLIMARAN,DELHI 13BAP0021 MOHD SHAKIR ANSARI ZAKIR HUSSAIN 13-2813 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION T-2,SEC-9,R.K PURAM, ND-22 13BAP0025 PUNEET KUMAR BALVEER SINGH 13-2818 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION HNO-B/113,NEW AVAS VIKAS,KASHIPUR,U.S.N, UTTRAKHAND-244713 13BAP0026 RAFIA TARIQ TARIQ JAMIL 13-2819 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION A-4,NADIR APT,NOOR NAGAR EXTN,JOHRI FARM,JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 13BAP0032 SAIYED IBREZ AHMED ABDUL REHMAN 13-2828 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION HNO-2696,GALI NO.67/A, BLOCK-E-2,NEAR 3RD 60 FEET ROAD,MOLARBAND EXTN,BADARPUR,ND 13BAP0035 SAMAN KARIM KARIMUDDIN 13-2832 1 PASSED FIRST DIVISION A-25,MASJID LANE,GALI NO.7,BATLA HOUSE, JAMIA NAGAR,ND-25 1 OFFICE OF THE CONTROLLER -

A Report on the Survey of North Bihar In·Relation To

leAk A REPORT ON THE SURVEY OF NORTH BIHAR IN· RELATION TO ..~;EFFECTS OF GANDAK & KOSI RIVER VALLEY PROJECTS ON THE FISHERIES OF THE AREA SU"'VEY RE.PORT I JAN.19SS NO.-? _ CENTRAL INLAND FISHER.IES RESEARCH INSTITUTE (fNOIAN COUNCfL OF AGAICULTUAAL RESEARCH) aA~RACI(PORE • W£st BENGAL. INDIA A REpORT ON THE SURVEY OF NORTH BIHAR IN RELATION TO EFFECTS OF GA~JDAK AND KOSI RIVER VALLEY PROJECTS ON THE FISHERIES OF THE AREA ----------- by H.P.C. Shetty & J.C. Malhotra CENTRAL INLAND FISHERIES RESEARCH SUBSTATION ALLAHABAD ,i~~ .~- ~ ONTE NTS ''''i, L.. '~ Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 " 2. FIELD SURV EY 2 2.1 Man 2 2.1.1 Champaran district 2 2.1.2 Muzaffarpur district 10 2.1.3 Other districts 10 2.2 Riverin8 fisheries 11 2.3 Tank and pond fisheries 14 3 DISCUSSION 16 3 •.1 Effect of river valley projects 16 3.2 Destruction of fry and fingerlings 18 f.rection of barriers ('bundhs') across inflow and outflow nalas 18 Effect of stagnant conditions due to lack of flushing 18 4 RE C OMf·'ENOA II ONS 18 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 23 6 REFERENCES 23 c. 1 INTRODUCTION Th~ Gandak and Kosi river ~yst~ms form an extensive network in North Bihar, in the districts of Saran, Champaran, MuzafTafpur, Sahersa, Darbhanga, Monghyr and Purnea. North Bihar as a whole may be treated as a vast inland delta, as all the principal rivers emer• ging from the Himalayas debouch in the plains and ultimately flow into the Ganga on the south. The process of this delta formation has been in pruYJ.:t;i:;;dlor -chousands of years by principal rivers like the Ghaghara, the Gandak, the Kamla and the Kosi by their h~avy silt and detritus load from the Himalayas.