Landseer's Highlands: a Place of Fascination With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

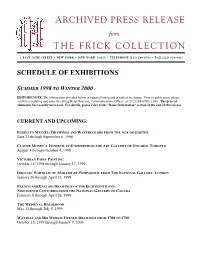

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SUMMER 1998 TO WINTER 2000 EDITORS NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm scheduling and dates by calling Heidi Rosenau, Communications Officer, at (212) 288-0700, x 264. The price of admission has recently increased. For details, please refer to the “Basic Information” section at the end of this release. CURRENT AND UPCOMING: FUSELI TO MENZEL: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLORS FROM THE AGE OF GOETHE June 23 through September 6, 1998 CLAUDE MONET’S VÉTHEUIL IN SUMMER FROM THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO, TORONTO August 4 through October 4, 1998 VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 DROUAIS’ PORTRAIT OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON January 26 through April 25, 1999 FRENCH AND ENGLISH DRAWINGS OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA February 8 through April 26, 1999 THE MEDIEVAL HOUSEBOOK May 11 through July 5, 1999 WATTEAU AND HIS WORLD: FRENCH DRAWINGS FROM 1700 TO 1750 October 18, 1999 through January 9, 2000 UPCOMING: VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Critically and commercially popular during the 19th century was the intriguing and distinctly British genre of Victorian fairy painting, the subject of an exhibition that comes this fall to The Frick Collection. The paintings and works on paper, roughly thirty in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from a comprehensive touring exhibition – the first of its type for this subject. -

Animal Painters of England from the Year 1650

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

William Holman Hunt's Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk Jennie Mae Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4920 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. Jennie Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Art History MA Thesis Spring 2017 Director: Catherine Roach Assistant Professor Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2017 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 Holman Hunt and Henry Monk: A Chance Meeting Chapter 2 Jan van Eyck: Rediscovery and Celebrity Chapter 3 Signs, Symbols and Text Conclusion List of Images Selected Bibliography Acknowledgements In writing this thesis I have benefitted from numerous individuals who have been generous with their time and encouragement. I owe a particular debt to Dr. Catherine Roach who was the thesis director for this project and truly a guiding force. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Eric Garberson and Dr. Kathleen Chapman who served on the panel as readers and provided valuable criticism, and Dr. Carolyn Phinizy for her insight and patience. -

Three Centuries of British Art

Three Centuries of British Art Three Centuries of British Art Friday 30th September – Saturday 22nd October 2011 Shepherd & Derom Galleries in association with Nicholas Bagshawe Fine Art, London Campbell Wilson, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Moore-Gwyn Fine Art, London EIGHTEENTH CENTURY cat. 1 Francis Wheatley, ra (1747–1801) Going Milking Oil on Canvas; 14 × 12 inches Francis Wheatley was born in Covent Garden in London in 1747. His artistic training took place first at Shipley’s drawing classes and then at the newly formed Royal Academy Schools. He was a gifted draughtsman and won a number of prizes as a young man from the Society of Artists. His early work consists mainly of portraits and conversation pieces. These recall the work of Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) and Benjamin Wilson (1721–1788), under whom he is thought to have studied. John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779), his friend and occasional collaborator, was also a considerable influence on him in his early years. Despite some success at the outset, Wheatley’s fortunes began to suffer due to an excessively extravagant life-style and in 1779 he travelled to Ireland, mainly to escape his creditors. There he survived by painting portraits and local scenes for patrons and by 1784 was back in England. On his return his painting changed direction and he began to produce a type of painting best described as sentimental genre, whose guiding influence was the work of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805). Wheatley’s new work in this style began to attract considerable notice and in the 1790’s he embarked upon his famous series of The Cries of London – scenes of street vendors selling their wares in the capital. -

Copyright Statement

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2017 Dogs and Domesticity Reading the Dog in Victorian British Visual Culture Robson, Amy http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/10097 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. i ii Dogs and Domesticity Reading the Dog in Victorian British Visual Culture by Amy Robson A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD Art History, 2017 Humanities and Performing Arts 2017 iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisors, Dr James Gregory and Dr Jenny Graham, for their ongoing support throughout this project. I would also like to extend immeasurable thanks to Dr Gemma Blackshaw, who was involved in the early and later stages of my research project. Each of these individuals brought with them insights, character, and wit which helped make the PhD process all the more enjoyable. -

An Ecorché Study of the Head of a Horse Black, Red and White Chalk on Blue-Grey Paper

Sir Edwin Landseer An Ecorché Study of the Head of a Horse Black, red and white chalk on blue-grey paper. A sketch of a lion and the torso of a youth in pencil on the verso. 500 x 310 mm. (19 3/8 x 12 1/4 in.) ACQUIRED BY THE SNITE MUSEUM OF ART, UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME, SOUTH BEND, INDIANA. Throughout his life, Edwin Landseer made countless studies and sketches of animals, in oil, watercolour, chalk and pencil. Most of these are unrelated to his larger finished paintings, and seem to have been done as exercises or to capture the appearance of an unusual animal or breed. This magnificent ecorché study of the head of a horse is among the finest of a small but significant group of anatomical studies of animals dating from the early years of Landseer’s independent career, which the artist kept among the contents of his studio until his death. Landseer had begun his formal training in 1815 with the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, who encouraged his young pupil to study the anatomy of various animals. Seven years later, Haydon recalled in his diary that Landseer ‘dissected animals under my eye, copied my anatomical drawings, and carried my principles of study into animal painting! His genius, thus tutored, has produced solid & satisfactory results.’ Haydon felt, however, that in later years Landseer did not credit the elder artist’s support and influence, noting in a diary entry of February 1824 that, ‘The higher a man is gifted by nature, the less willing he is always to acknowledge any obligation to any other being, however just or decent. -

2015 · Maastricht TEFAF: the European Fine Art Fair 13–22 March 2015 LONDON MASTERPIECE LONDON 25 June–1 July 2015 London LONDON ART WEEK 3–10 July 2015

LOWELL LIBSON LTD 2 015 • New York · annual exhibition British Art: Recent Acquisitions at Stellan Holm · 1018 Madison Avenue 23–31 January 2015 · Maastricht TEFAF: The European Fine Art Fair 13–22 March 2015 LONDON MASTERPIECE LONDON 25 June–1 July 2015 London LONDON ART WEEK 3–10 July 2015 [ B ] LOWELL LIBSON LTD 2 015 • INDEX OF ARTISTS George Barret 46 Sir George Beaumont 86 William Blake 64 John Bratby 140 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf John Constable 90 Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 John Singleton Copley 39 Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 Email: [email protected] John Robert Cozens 28, 31 Website: www.lowell-libson.com John Cranch 74 John Flaxman 60 The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday The entrance is in Old Burlington Street Edward Onslow Ford 138 Thomas Gainsborough 14 Lowell Libson [email protected] Daniel Gardner 24 Deborah Greenhalgh [email protected] Thomas Girtin 70 Jonny Yarker [email protected] Hugh Douglas Hamilton 44 Cressida St Aubyn [email protected] Sir Frank Holl 136 Thomas Jones 34 Sir Edwin Landseer 112 Published by Lowell Libson Limited 2015 Richard James Lane 108 Text and publication © Lowell Libson Limited Sir Thomas Lawrence 58, 80 All rights reserved ISBN 978 0 9929096 0 4 Daniel Maclise 106, 110 Designed and typeset in Dante by Dalrymple Samuel Palmer 96, 126 Photography by Rodney Todd-White & Son Ltd Arthur Pond 8 Colour reproduction by Altaimage Printed in Belgium by Albe De Coker Sir Joshua Reynolds 18 Cover: a sheet of 18th-century Italian George Richmond 114 paste paper (collection: Lowell Libson) George Romney 36 Frontispiece: detail from Thomas Rowlandson 52 William Turner of Oxford 1782–1862 The Sands at Barmouth, North Wales Simeon Solomon 130 see pages 116–119 Francis Towne 48 Overleaf: detail from William Turner of Oxford 116 John Robert Cozens 1752–1799, An Alpine Landscape, near Grindelwald, Switzerland J.M.W. -

Sir Edwin Landseer, As He Was Now Known, Produced Many of His Finest Works

THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/siredwinlandseerOOunse tfolk &ono;tf »»* £ouq;£ tfov <£!)(Itor*n EDITED BY JANE BYRD RADCLIFFE-WHITEHEAD HE most remarkably complete, comprehensive and interesting collection of English, Scottish, TIrish, German, French, Scandinavian, Polish and Russian, Italian, Spanish and American songs ever gotten together. In addition to the folk songs are : Songs of Patriotism of Various Nations, Carols, Rounds, Catches, Nursery Songs, Lullabies, etc., showing the most thorough knowledge, intense enthusiasm, and excellent musical training, and judgment in gathering, selecting and compiling, on the part of the author. A treasury of melody and of musical expression found only in songs of this class, delightful to the adult lover of music and especially adapted for the young. PRICE — 226 pages, folio size, bound in board cover with cloth back, $2.00 Sent prepaid on receipt of price OLIVER DITSON COMPANY, BOSTON, MASS. Chas. H. Ditson & Co., New York J. E. Ditson & Co., Philadelphia B133 BRAUN’S CARBON PRINTS FINEST AND MOST DURABLE IMPORTED WORKS OF ART NE HUNDRED THOUSAND direct reproductions from the original paintings and drawings by old and modern masters in the galleries of Amsterdam, Antwerp, Berlin, Dres- den, Florence, Haarlem, Hague, London, Ma- drid, Milan, Paris, St. Petersburg, Rome, Venice, Vienna, Windsor, and others. Special Terms to Schools BRAUN, CLEMENT & CO. 249 Fifth Avenue, corner 28th Street NEW YORK CITY In answering advertisements, please mention Masters in Art MASTERS IN ART *1 Exercise Your Skin Keep up its activity, and aid its natural changes, not by expensive Turkish baths, but by Hand Sapolio, the only soap that liberates the activities of the pores without working chemical changes. -

Dispelling the Myths Surrounding Nineteenth-Century British

Recommended book: Shearer West, Portraiture, Oxford History of Art, (£10.34 on Amazon). An introduction to portraiture through the centuries. • Portraits were the most popular category of painting in Britain and the mainstay of most artists earnings. There are therefore thousands of examples of portraits painted throughout the nineteenth century. I have chosen a small number of portraits that tell a story and link together some of the key artists of the nineteenth century while illustrating some of the most important aspects of portrait painting. • In the second exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1769 of the 265 objects a third were portraits, sixty years later, in 1830, of 1,278 objects half were portraits of which 300 were miniatures or small watercolours or and 87 sculptures. In the next 40 years photography became a thriving business, and in 1870 only 247, a fifth, of the 1,229 exhibits were portraits but only 32 were miniatures. Portrait sculptures, which photography could not emulate, increased to 117. • The unique thing about portrait paintings is that a recognisable likeness is a prerequisite and so the many fashions in modern art have had little impact on portrait painting. • The British have always been fascinated by the face of the individual. • Portraits had various functions: • Love token or family remembrance • Beauty, the representation of a particular woman because of her beauty (ideal beauties were painted but were not portraits) • Record for prosperity of famous or infamous people • Moral representation of the ‘great and the good’ to emulate. Renaissance portraits represented the ‘great and the good’ and this desire to preserve the unique physical appearance of ‘great men’ continued into the 19th century with Watts ‘House of Fame’. -

British Canvas, Stretcher and Panel Suppliers' Marks

British canvas, stretcher and panel suppliers’ marks: Part 3, Thomas Brown, 1805-54 This resource surveys suppliers’ marks on the reverse of picture supports. Thomas Brown (c.1778-1840) was in business from 1805/6. He was followed by his son, also Thomas Brown. For fuller details, see British artists' suppliers, 1650-1950 - B. In their day, the Browns were the business of choice among many professional artists. In 1842 the younger Brown claimed that he, his father, and his father's predecessor, had between them supplied all the Royal Academy’s Presidents up to that time, and that they had been the favoured servants of the Academy since its foundation (The Art-Union, January 1842). Thomas Brown’s marks can be conveniently divided, more or less chronologically, according to addresses: High Holborn, then 163 High Holborn and finally and briefly 260 Oxford St. Such was the volume of Brown’s business that it is likely that several similar stamps were in use at any one time. Canvas stamps and stencils are treated first (sections 1 to 8). They have been subject to studies by Martin Butlin and Norman Muller (note 4). For panels and some stretchers Brown used a small label (section 9) or an impressed mark (section 10). Most of Brown's rivals preferred to use conspicuous printed labels, especially on millboards, a type of support Brown did not favour. Measurements of marks, given where known, are approximate and may vary according to the stretching or later conservation treatment of a canvas or the trimming of a label. -

The Preraphaelites, 1840-1860

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • Our sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN 1. The History of the Tate 2. From Absolute Monarch to Civil War, 1540-1650 3. From Commonwealth to the Georgians, 1650-1730 4. The Georgians, 1730-1780 5. Revolutionary Times, 1780-1810 6. Regency to Victorian, 1810-1840 7. William Blake 8. J. M. W. Turner 9. John Constable 10. The Pre-Raphaelites, 1840-1860 West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Sir Edwin Landseer's Rent-Day in the Wilderness, 1868

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2015 Meet the Masters: Highlights from the Scottish National Gallery Sir Edwin Landseer’s Rent-day in the Wilderness, 1868 Alison Inglis 26/27 August 2015 Lecture summary: This lecture will examine Sir Edwin Landseer’s late work, Rent-day in the Wilderness, 1868. In addition to placing this painting in the context of Landseer’s career as one of the leading artists of the Victorian era, the lecture will also consider the work from a number of different perspectives, including the significance of the subject matter and the role of the patron; the shift from history painting to historical genre painting during the early nineteenth century; the influence of Sir Walter Scott on the depiction of Scottish subject matter; and Landseer’s reputation as a celebrated animal painter. Slide list: 1. Sir Edwin Landseer, The Connoisseurs, c.1865, oil on canvas, Royal Collection 2. Edwin Landseer, Rent-day in the Wilderness, 1868, Oil on canvas, National Gallery of Scotland 3. Sir Edwin Landseer, A Scene in the Grampians – The Drovers’ Departure, c.1835 Oil on canvas, V&A Museum 4. Sir Walter Scott, 1st Bart, c.1824, Oil on panel, National Portrait Gallery 5. John Millais, Diana Vernon, 1880, oil on canvas, National Gallery of Victoria, Felton Bequest, 1914 6. John Millais, The Bride of Lammermoor, 1878, Oil on canvas, Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives 7. Sir Edwin Landseer, A Scene at Abbotsford, c.1827, Oil on panel, Tate London 8. Stephen Pearce, Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1856, Oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, London 9.