The Preraphaelites, 1840-1860

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Portraiture Through the Centuries

• The aim of the course is look at nineteenth-century British art in new ways and so to dispel the myths. One of these myths is that France was the only country in the nineteenth century where artists innovated and another is that British art was wholly derivative from French art. These myths first arose in the early twentieth century because of the rapid changes that took place in Britain at the end of the Victorian period. The anti-Victorian rhetoric was fuelled by a small number of British commentators and art historians who valorised French art and criticized British art. I will show that Victorian art was lively, innovative and exciting and reflected the history and culture of the period. • Art reflects the social conventions and expectations of the period and in Britain’s rapidly changing industrial society there were many controversial innovations and styles. We shall see how Britain's lead in the industrial revolution and its growing population and wealth led to new markets for art. It also led both to a new confidence offset by a respect for the classical period and a nostalgia for an imagined romantic medieval period. The gradual emancipation of the poor, workers and woman was reflected in a number of art works of the period. • My background: a degree in art and architecture from Birkbeck College, followed by an MA from the Courtauld Institute where I specialised in nineteenth century art and a PhD from the University of Bristol. I have published various papers including parts of two books and I have spoken at conferences here and in the USA. -

Pre-Raphaelites. an Extraordinary Exhibition in Milan

Ressort: Kunst, Kultur und Musik Pre-Raphaelites. An extraordinary Exhibition in Milan Rome/Milan, 05.06.2019 [ENA] In 1848, political and social revolutions involving almost all nations break out in Europe. In England, seven students joined to produce an artistic revolution: freeing British painting from conventions and dependence on old masters. The group's intention was to reform art by rejecting what it considered the mechanistic approach first adopted by Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. The men and women of the so-called Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) experienced new beliefs, new lifestyles and personal relationships, as radical as their art. Their splendid paintings will be on exhibition for the first time in Milan thanks to the extraordinary collaboration project between Palazzo Reale Milan and Tate Britain.The exhibition “Preraffaelliti. Amore e desiderio” (Pre-Raphaelites. Love and desire ), promoted and produced by the Municipality of Milan-Culture, Palazzo Reale and 24 ORE Cultura-Gruppo 24 ORE is organized in collaboration with Tate and curated by Carol Jacobi, Curator British Art of the London museum. Maria Teresa Benedetti’s scientific contribution highlited the relationship of the Pre-Raphaelites with Italy. It will thus be possible to admire about 80 works in Milan, together with some iconic paintings difficult to see outside of the UK, such as the Ophelia by John Everett Millais, The Awakening of Consciousness by William Holman Hunt, Love of April by Arthur Hughes, the Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse.The Palazzo Reale exhibition, open to the public from 19 June to 6 October 2019, reveals the universe of art and values of the 18 pre-Raphaelite artists. -

The Afterglow in Egypt Teachers' Notes

Teacher guidance notes The Afterglow in Egypt 1861 A zoomable image of this painting is available by William Holman Hunt on our website to use in the classroom on an interactive whiteboard or projector oil on canvas 82 x 37cm www.ashmolean.org/learning-resources These guidance notes are designed to help you use paintings from our collection as a focus for cross- curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see the painting offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Starting questions Questions like these may be useful as a starting point for developing speaking and listening skills with your class. What catches your eye first? What is the lady carrying? Can you describe what she is wearing? What animals can you see? Where do you think the lady is going? What do you think the man doing? Which country do you think this could be? What time of day do you think it is? Why do you think that? If you could step into the painting what would would you feel/smell/hear...? Background Information Ideas for creative planning across the KS1 & 2 curriculum The painting You can use this painting as the starting point for developing pupils critical and creative thinking as well as their Hunt painted two verions of ‘The Afterglow in Egypt’. The first is a life-size painting of a woman learning across the curriculum. You may want to consider possible ‘lines of enquiry’ as a first step in your cross- carrying a sheaf of wheat on her head, which hangs in Southampton Art Gallery. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

PRE-RAPHAELITES: DRAWINGS and WATERCOLOURS Opening Spring 2021, (Dates to Be Announced)

PRESS RELEASE 5 February 2021 for immediate release: PRE-RAPHAELITES: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS Opening Spring 2021, (dates to be announced) Following the dramatic events of 2020 and significant re-scheduling of exhibition programmes, the Ashmolean is delighted to announce a new exhibition for spring 2021: Pre-Raphaelites: Drawings and Watercolours. With international loans prevented by safety and travel restrictions, the Ashmolean is hugely privileged to be able to draw on its superlative permanent collections. Few people have examined the large number of Pre-Raphaelite works on paper held in the Western Art Print Room. Even enthusiasts and scholars have rarely looked at more than a selection. This exhibition makes it possible to see a wide range of these fragile works together for the first time. They offer an intimate and rare glimpse into the world of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the artists associated with the movement. The exhibition includes works of extraordinary beauty, from the portraits they made of each other, studies for paintings and commissions, to subjects taken from history, literature and landscape. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) In 1848 seven young artists, including John Everett Millais, William The Day Dream, 1872–8 Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, resolved to rebel against the Pastel and black chalk on tinted paper, 104.8 academic teaching of the Royal Academy of Arts. They proposed a × 76.8 cm Ashmolean Museum. University of Oxford new mode of working, forward-looking despite the movement’s name, which would depart from the ‘mannered’ style of artists who came after Raphael. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) set out to paint with originality and authenticity by studying nature, celebrating their friends and heroes and taking inspiration from the art and poetry about which they were passionate. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

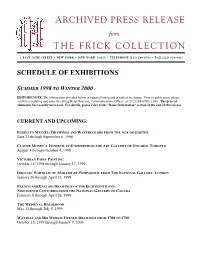

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SUMMER 1998 TO WINTER 2000 EDITORS NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm scheduling and dates by calling Heidi Rosenau, Communications Officer, at (212) 288-0700, x 264. The price of admission has recently increased. For details, please refer to the “Basic Information” section at the end of this release. CURRENT AND UPCOMING: FUSELI TO MENZEL: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLORS FROM THE AGE OF GOETHE June 23 through September 6, 1998 CLAUDE MONET’S VÉTHEUIL IN SUMMER FROM THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO, TORONTO August 4 through October 4, 1998 VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 DROUAIS’ PORTRAIT OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON January 26 through April 25, 1999 FRENCH AND ENGLISH DRAWINGS OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA February 8 through April 26, 1999 THE MEDIEVAL HOUSEBOOK May 11 through July 5, 1999 WATTEAU AND HIS WORLD: FRENCH DRAWINGS FROM 1700 TO 1750 October 18, 1999 through January 9, 2000 UPCOMING: VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Critically and commercially popular during the 19th century was the intriguing and distinctly British genre of Victorian fairy painting, the subject of an exhibition that comes this fall to The Frick Collection. The paintings and works on paper, roughly thirty in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from a comprehensive touring exhibition – the first of its type for this subject. -

Art in the Modern World

Art in the Modern World A U G U S T I N E C O L L E G E Beata Beatrix 1863 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI The Girlhood of Mary 1849 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Ecce ancilla Domini 1850 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Our English Coasts William Holman HUNT | 1852 Our English Coasts detail 1852 William Holman HUNT The Hireling Shepherd 1851 | William Holman HUNT The Awakening Conscience 1853 William Holman HUNT The Scapegoat 1854 | William Holman HUNT The Shadow of Death 1870-73 William Holman HUNT Christ in the House of His Parents 1849 | John Everett MILLAIS Portrait of John Ruskin 1854 John Everett MILLAIS Ophelia 1852 | John Everett MILLAIS George Herbert at Bemerton 1851 | William DYCE The Man of Sorrows 1860 | William DYCE Louis XIV & Molière 1862 | Jean-Léon GÉRÔME Harvester 1875 William BOUGUEREAU Solitude 1890 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Seaside 1878 James Jacques Joseph TISSOT The Awakening Heart 1892 William BOUGUEREAU The Beguiling of Merlin 1874 | Edward BURNE JONES Innocence 1873 William BOUGUEREAU Bacchante 1894 William BOUGUEREAU The Baleful Head 1885 Edward BURNE JONES Springtime 1873 Pierre-Auguste COT The Princesse de Broglie James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Woman of Ambition 1883-85 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Prayer in Cairo Jean-Léon GEROME The Boyhood of Raleigh 1870 | John Everett MILLAIS Flaming June 1895 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Lady Lilith 1864 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Holyday 1876 | James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Autumn on the Thames 1871 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the Ford 1857 | John Everett MILLAIS A Reading -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY of IRELAND

National Gallery of Ireland Gallery of National Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Annual Report nationalgallery.ie Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 02 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Our mission is to care for, interpret, develop and showcase art in a way that makes the National Gallery of Ireland an exciting place to encounter art. We aim to provide an outstanding experience that inspires an interest in and an appreciation of art for all. We are dedicated to bringing people and their art together. 03 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND 04 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Contents Introducion 06 Chair’s Foreword 06 Director’s Review 10 Year at a Glance 2017 14 Development & Fundraising 20 Friends of the National Gallery of Ireland 26 The Reopening 15 June 2017 34 Collections & Research 51 Acquisition Highlights 52 Exhibitions & Publications 66 Conservation & Photography 84 Library & Archives 90 Public Engagement 97 Education 100 Visitor Experience 108 Digital Engagement 112 Press & Communications 118 Corporate Services 123 IT Department 126 HR Department 128 Retail 130 Events 132 Images & Licensing Department 134 Operations Department 138 Board of Governors & Guardians 140 Financial Statements 143 Appendices 185 Appendix 01 \ Acquisitions 2017 186 Appendix 02 \ Loans 2017 196 Appendix 03 \ Conservation 2017 199 05 NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND Chair’s Foreword The Gallery took a major step forward with the reopening, on 15 June 2017, of the refurbished historic wings. The permanent collection was presented in a new chronological display, following extensive conservation work and logistical efforts to prepare all aspects of the Gallery and its collections for the reopening. -

Victorian Visions

AUDIO TOUR TRANSCRIPTS Art GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WaLES AUDIO TOUR www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/audiotours VICTORIAN VISIONS John William Waterhouse Mariamne, 1887, John Schaeffer Collection Photo Dallan Wright © Eprep/FOV Editions VICTORIAN VISIONS audio tour 1. RICHARD REDGravE THE SEMPSTRESS 1846 Richard Redgrave’s painting The sempstress shows a This is a highly important painting because it’s one of poor young woman sitting in a garret stitching men’s the very first works in which art is used as a medium shirts. It’s miserably low-paid work and to make of campaigning social commentary on behalf of the ends meet she has to work into the early hours of poor. The industrial revolution in Britain brought with the morning. So as you can tell by the clock – the it a goodly share of social problems and as the century time is now 2.30 am. Through the window the sky is progressed, these would frequently furnish painters streaked with moonlight. And the lighted window of a with subject matter. But in the 1840s, when Redgrave neighbouring house suggests that the same scene is painted this picture, the idea of an artist addressing repeated on the other side of the street. himself to social questions was something completely new. The sempstress’ eyes are swollen and inflamed with all And it seems there was a personal dimension for the that close work she is having to do by the inadequate artist because Richard Redgrave didn’t come from a light of a candle. On the table you can find the rich family and his sister had been forced to leave home instruments of her trade: her work basket, her needle and find employment as a governess.