Introduction to Portraiture Through the Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Hylas and the Matinée Girl: John William Waterhouse and the Female Gaze

Hylas and the Matinée Girl: John William Waterhouse and the Female Gaze Jennifer Bates Ehlert British painter John William Waterhouse (1849-1917), One trend was the emergence of the female gaze during is best known for paintings of beguiling women, such as The the late nineteenth century, a gaze which is evident in paint- Lady of Shalott and La Belle Dame Sans Merci. Dedicated to the ings such as Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896, The Awakening power and vulnerability of the female form, he demonstrated of Adonis, 1900, and Echo and Narcissus, 1903 (see Figures the Victorian predilection for revering and fearing the feminine. 1 and 2). These paintings could be read as commentary on Often categorized as a Pre-Raphaelite or a Classical Academy the rise of the male figure as a spectacle and the impact of painter, Waterhouse was enamored of femme fatales and tragic the female gaze. Specifically, this paper correlates the actions damsels, earning him a reputation as a painter of women. and gaze of the nymphs in Hylas and the Nymphs to that Nonetheless, the men in Waterhouse’s art warrant scholarly of the matinée girl. Matinée girls, a late nineteenth-century attention and their time is due. Simon Goldhill’s article, “The social phenomena, discomfited theater audiences with their Art of Reception: J.W. Waterhouse and the Painting of Desire freedom and open admiration of actors. in Victorian Britain,” recognizes the significance of the male Although Waterhouse’s artworks have and do lend subject in Waterhouse’s oeuvre, writing, “His classical pictures themselves to discussions within the realm of queer gaze and in particular show a fascinating engagement with the position theory, it is purposefully avoided because the focus here is of the male subject of desire, which has been largely ignored in the rarely discussed female gaze. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti •William Holman Hunt •John Everett Millais

ArtH 2257 19th Century Art Realism vs. Symbolism Robert Campin: The Merode Altarpiece, 1425-28 Robert Campin: The Merode Altarpiece, 1425-28 Jan van Eyck: Arnolfini Wedding. 1434 Jan van Eyck, Arnolfini Wedding, 1434 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 Augustus Egg: Past and Present, 1858 G.F. Watts: Found Drowned, 1849-50 Richard Redgrave: The Poor Teacher, 1845 Gustave Dore: Orange Court, Drury Lane, illustration in in B. Jerrold, London, a Pilgrimage,1872 The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Founded 1848 by: •Dante Gabriel Rossetti •William Holman Hunt •John Everett Millais Rossetti Millais Hunt Julia Margaret Cameron: William Holman Hunt, 1850 WH Hunt: Early Britons Sheltering Christian Missionary from Druids, 1850 William Holman Hunt, The Hireling Shepherd, 1851 William Holman Hunt, The Hireling Shepherd, 1851 William Holman Hunt, The Hireling Shepherd, 1851 WH Hunt: The Awakening Conscience, 1852 WH Hunt: The Awakening Conscience, 1852 WH Hunt: The Awakening Conscience, 1852 WH Hunt: The Awakening Conscience, 1852 WH Hunt: The Awakening Conscience, 1852 Jan van Eyck: Arnolfini Wedding. 1434 Ford Maddox Brown, Take Your Son, Sir!, 1852-59; 1892 (unfinished) Ford Maddox Brown, Take Your Son, Sir!, 1852-59; 1892 (unfinished) John E. Millais: Lorenzo and Isabella, 1849 John E. Millais: Ophelia, 1851-2 John E. Millais: Ophelia, 1851-2 John E. Millais: Mariana, 1851 John E. Millais: Mariana, 1851 John E. Millais: Mariana, 1851 John E. Millais: Mariana, 1851 John E. -

Interiors in Victorian Painting

Women as Vestals of the Domestic Hearth: Interiors in Victorian Painting Simone Neuhauser M.A., Institute of Art History, University of Bern Ph.D. project. Supervisors: Prof. Norberto Gramaccini and Prof. Horst Bredekamp. My dissertation project, “Constructions of the Feminine Interior”, examines representations of women in interior spaces of contemporary paintings in Victorian England. The role of women in their dissociation from both men and other women are the object of my research. I proceed on the assumption that the spaces surrounding women are representations of the inner self of the figure being represented. I intend to demonstrate that representations of women in paintings contain within them a brisance similar to the portrayals of women by literary figures in novels and poetry of the same time. Therefore I will look at writers such as Emily Brontë, Henry James and Tennyson’s Moxon edition, which itself links the written and visual world. In addition works by the painters John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Elizabeth Siddal are examined. Painting and literature are thereby viewed in close connection and compared to one another using the reception theory. My dissertation will identify the various views of women with the aid of a social historical and psychoanalytical approach. Therefore studies such as those by art historians Elizabeth Prettejohn and Allan Staley will be touched upon. This theoretical view will be enhanced by studies of exhibitions, the latest being ‘The Cult of Beauty’ in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2011. I wish to show that “space” serves as a canvas for gender roles. -

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood: Painting

Marek Zasempa THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: PAINTING VERSUS POETRY SUPERVISOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga Completed in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. UNIVERSITY OF SILESIA KATOWICE 2008 Marek Zasempa BRACTWO PRERAFAELICKIE – MALARSTWO A POEZJA PROMOTOR: prof. dr hab. Wojciech Kalaga UNIWERSYTET ŚLĄSKI KATOWICE 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER 1: THE PRE-RAPHAELITE BROTHERHOOD: ORIGINS, PHASES AND DOCTRINES ............................................................................................................. 7 I. THE GENESIS .............................................................................................................................. 7 II. CONTEMPORARY RECEPTION AND CRITICISM .............................................................. 10 III. INFLUENCES ............................................................................................................................ 11 IV. THE TECHNIQUE .................................................................................................................... 15 V. FEATURES OF PRE-RAPHAELITISM: DETAIL – SYMBOL – REALISM ......................... 16 VI. THEMES .................................................................................................................................... 20 A. MEDIEVALISM ........................................................................................................................................ -

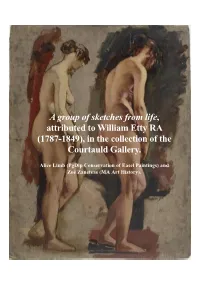

A Group of Sketches from Life, Attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the Collection of the Courtauld Gallery

A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings) and Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History). Zoë Zaneteas and Alice Limb Painting Pairs 2019 A group of sketches from life, attributed to William Etty RA (1787-1849), in the collection of the Courtauld Gallery. This report was produced as part of the Painting Pairs project and is a collaboration between Zoë Zaneteas (MA Art History) and Alice Limb (PgDip Conservation of Easel Paintings).1 Aims of the Project This project focusses on a group of seven sketches on board, three of which are double sided, which form part of the Courtauld Gallery collection. We began this project with three overarching aims: firstly, to contextualize the attributed artist, William Etty, within the artistic, moral and social circumstances of his time and revisit existing scholarship; secondly, to examine the works from a technical and stylistic perspective in order to establish if their attribution is justified and, if not, whether an alternative attribution might be proposed; finally, to treat one of the works (CIA2583), including decisions on whether the retention of material relating to the work’s early physical history was justified and if this material further informs our knowledge of Etty’s practice. It must be noted that Etty was a prolific artist during the forty years he was active, and that a vast amount of artistic and archival material (both critical and personal) relates to him. This study will 1 Special thanks must go to: the staff of the Courtauld Gallery (especially Dr Karen Serres, Kate Edmondson and Graeme Barraclough), the staff of the Department of Conservation and Technology (especially Clare Richardson, Dr Pia Gotschaller and Professor Aviva Burnstock), Dr Beatrice Bertram of York City Art Gallery, Jevon Thistlewood and Morwenna Blewett of the Ashmolean Museum, and the staff of the Royal Academy Library, Archives and Stores (especially Helen Valentine, Annette Wickham, Mark Pomeroy, and Daniel Bowman). -

The Woman Painter in Victorian Literature

The Woman Painter in Victorian Literature The Woman Painter in Victorian Literature A NTONI A L OS A NO The Ohio State University Press Columbus Cover: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, A Parable of Love (Love’s Mirror). Reproduced by permis- sion of the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery. Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Losano, Antonia Jacqueline. The woman painter in Victorian literature / Antonia Losano. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1081-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1081-3 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. English fiction—19th century—History and criticism. 2. English fiction—Women authors—History and criticism. 3. Art and literature—Great Britain—History—19th century. 4. Women artists in literature. 5. Aesthetics in literature. 6. Feminism in litera- ture. 7. Art in literature. I. Title. PR878.W6L67 2008 823.009'9287—dc22 2007028410 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1081-9) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9160-3) Cover design by Melissa Ryan Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Type design by Juliet Williams Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 In Memoriam Sarah Louise DeRolph Wampler 1908–2000 - C ONTENTS , List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction Chapter One Prevailing -

Paul Barlow Imagining Intimacy

J434 – 01-Barlow 24/3/05 1:06 pm Page 15 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Paul Barlow Imagining Intimacy: Rhetoric, Love and the Loss of Raphael This essay is concerned with intimacy in nineteenth-century art, in particular about an imagined kind of intimacy with the most admired of all artists – Raphael. I will try to demonstrate that this preoccupation with intimacy was a distinctive phenomenon of the period, but will concentrate in particular on three pictures about the process of painting emotional intimacy, all of which are connected to the figure of Raphael. Raphael was certainly the artist who was most closely associated with this capacity to ‘infuse’ intimacy into his art. As his biographers Crowe and Cavalcaselle wrote in 1882, Raphael! At the mere whisper of the magic name, our whole being seems spell-bound. Wonder, delight and awe, take possession of our souls, and throw us into a whirl of contending emotions … [He] infused into his creations not only his own but that universal spirit which touches each spectator as if it were stirring a part of his own being. He becomes familiar and an object of fondness to us because he moves by turns every fibre of our hearts … His versatility of means, and his power of rendering are all so varied and so true, they speak so straightforwardly to us, that we are always in commune with him.1 It is this particular ‘Raphaelite’ intimacy that I shall be exploring here, within the wider context of the transformations of History Painting in the period. -

19Th Century European, Victorian and British Impressionist Art New Bond Street, London I 26 September 2018

19th Century European, Victorian and British Impressionist Art New Bond Street, London I 26 September 2018 19th Century European, Victorian and British Impressionist Art Wednesday 26 September 2018 at 2pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES REGISTRATION PHYSICAL CONDITION OF Thursday 20 September Peter Rees (Head of Sale) IMPORTANT NOTICE LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8201 Please note that all customers, PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS Friday 21 September [email protected] irrespective of any previous NO REFERENCE IN THIS 9am to 4.30pm activity with Bonhams, are Sunday 23 September Charles O’Brien CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL 11am to 3pm (Head of Department) required to complete the Bidder CONDITION OF ANY LOT. Monday 24 September +44 (0) 20 7468 8360 Registration Form in advance of INTENDING BIDDERS MUST 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] the sale. The form can be found SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO Tuesday 25 September at the back of every catalogue THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT 9am to 4.30pm Emma Gordon and on our website at www. AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 Wednesday 26 September +44 (0) 20 7468 8232 bonhams.com and should be OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS 9am to 12pm [email protected] returned by email or post to the CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS CATALOGUE. specialist department or to the SALE NUMBER Alistair Laird bids department at 24742 +44 (0) 20 7468 8211 As a courtesy to intending [email protected] [email protected] bidders, Bonhams will provide a written Indication of the physical CATALOGUE To bid live online and / or leave condition of lots in this sale if a £25.00 Deborah Cliffe internet bids please go to +44 (0) 20 7468 8337 request is received up to 24 www.bonhams.com/ ILLUSTRATIONS [email protected] hours before the auction starts. -

Neo-Pre-Raphaelitism: the Final Generations

Neo-Pre-Raphaelitism: The Final Generations Amanda B. Waterman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair Stuart Lingo Joseph Butwin Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art History ©Copyright 2016 Amanda B. Waterman University of Washington Abstract Neo Pre-Raphaelitism: The Final Generations Amanda B. Waterman Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan P. Casteras Art History The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of seven young men who wanted to rebel against the teachings and orthodoxies of the Royal Academy. It was a short-lived movement, beginning in 1848 and ending in the early 1850s, but this dissertation will argue that their influence lived on and inspired a group of artists who were working at the turn of the century and well into the twentieth-century. This dissertation is unprecedented; it is the first publication which aims to specifically categorize certain artists whose oeuvres are indebted to various generations of Pre-Raphaelitism. In short, I am characterizing these artists and thereby dubbing them “Neo-Pre-Raphaelite,” channeling an early twentieth-century description of some of these artists. The most obvious reason to refer to them by this term is that they are stylistically and/or thematically linked to members of the original PRB or later generations / manifestations of Pre-Raphaelitism. The individuals on whom I am focusing are all British and produced Pre-Raphaelite inspired work from roughly 1895-1950. Consequently, the parameters within which I am working are threefold; firstly, the artists were exhibiting in the late 1880s/1890 – 1920 (a Neo-Pre-Raphaelite period that overlapped for most of them); secondly, those whose work echoed that of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; and thirdly, persons having a working relationship with Edwin Austin Abbey—an American artist who was in a unique position to be a hybrid between the earlier PRB and these younger artists. -

Roger Fenton

Roger Fenton PASHA AND BAYADERE Roger Fenton PASHA AND BAYADERE Gordon Baldwin GETTY MUSEUM STUDIES ON ART Los ANGELES Christopher Hudson, Publisher Cover: Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869). Pasha and Bayadere, 1858 [detail]. William Peterson, Editor Albumen print, 45 x 36.3 cm (17 "Ae x 14 V4 in.). Eileen Delson, Designer Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum (84.XP.219.32). Jeffrey Cohen, Series Designer Stacy Miyagawa, Production Coordinator Frontispiece: Ellen Rosenbery Photographer Roger Fenton. Self-Portrait in Zouave Uniform, 1855. © 1996 The J. Paul Getty Museum Albumen print, 17.3 x 15.3 cm (6I3/i6 x 6 in.). 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum (84.XM.io28.i7). Malibu, California 90265-5799 Mailing address: All works of art are reproduced (and photographs P.O. Box 2112 provided) courtesy of the owners unless otherwise Santa Monica, California 90407-2112 indicated. Library of Congress Typography by G 8i S Typesetters, Inc., Cataloging-in-Publications Data Austin, Texas Printed by C & C Offset Printing Co., Ltd., Baldwin, Gordon. Hong Kong Roger Fenton : Pasha and Bayadere / [Gordon Baldwin]. p. cm. (Getty Museum studies on art) ISBN 0-89236-367-3 i. Photography, Artistic. 2. Portrait photog- raphy. 3. Fenton, Roger, 1819-1869. I. Fenton, Roger, 1819-1869. II. Title. III. Series. TR652.B35 1996 77o'.092-DC20 96-1755 CIP CONTENTS Through Victorian Eyes: An Inventory of a Photograph i Etudes: Fenton and French Orientalism 22 Travelers' Notes and Poet's License: British Pictorial