The Royal Academy of Arts and Its Anatomical Teachings; with an Examination of the Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shearer West Phd Thesis Vol 1

THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON (VOL. I) Shearer West A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 1986 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2982 This item is protected by original copyright THE THEATRICAL PORTRAIT IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY LONDON Ph.D. Thesis St. Andrews University Shearer West VOLUME 1 TEXT In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the I work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. ABSTRACT A theatrical portrait is an image of an actor or actors in character. This genre was widespread in eighteenth century London and was practised by a large number of painters and engravers of all levels of ability. The sources of the genre lay in a number of diverse styles of art, including the court portraits of Lely and Kneller and the fetes galantes of Watteau and Mercier. Three types of media for theatrical portraits were particularly prevalent in London, between ca745 and 1800 : painting, print and book illustration. -

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and Their Relations with Artists

Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their relations with artists Vanessa Remington Essays from two Study Days held at the National Gallery, London, on 5 and 6 June 2010. Edited by Susanna Avery-Quash Design by Tom Keates at Mick Keates Design Published by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012. Royal Collection Enterprises Limited St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1JR www.royalcollection.org ISBN 978 1905686 75 9 First published online 23/04/2012 This publication may be downloaded and printed either in its entirety or as individual chapters. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for non-commercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses please contact Royal Collection Enterprises Limited. www.royalcollection.org.uk Victoria Albert &Art & Love Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their relations with artists Vanessa Remington Victoria and Albert: Art and Love, a recent exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, was the first to concentrate on the nature and range of the artistic patronage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. This paper is intended to extend this focus to an area which has not been explored in depth, namely the personal relations of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the artists who served them at court. Drawing on the wide range of primary material on the subject in the Royal Archive, this paper will explore the nature of that relationship. It will attempt to show how Queen Victoria and Prince Albert operated as patrons, how much discretion they gave to the artists who worked for them, and the extent to which they intervened in the creative process. -

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: the Very English Ambience of It All

Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Hillstrom Museum of Art SEE PAGE 14 Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All September 12 through November 6, 2016 Opening Reception Monday, September 12, 2016, 7–9 p.m. Nobel Conference Reception Tuesday, September 27, 2016, 6–8 p.m. This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Katie Penkhus, who was an art history major at Gustavus Adolphus College, was an accomplished rider and a lover of horses who served as co-president of the Minnesota Youth Quarter Horse Association, and was a dedicated Anglophile. Hillstrom Museum of Art HILLSTROM MUSEUM OF ART 3 DIRECTOR’S NOTES he Hillstrom Museum of Art welcomes this opportunity to present fine artworks from the remarkable and impressive collection of Dr. Stephen and Mrs. Martha (Steve and Marty) T Penkhus. Animal and Sporting Paintings in the Penkhus Collection: The Very English Ambience of It All includes sixty-one works that provide detailed glimpses into the English countryside, its occupants, and their activities, from around 1800 to the present. Thirty-six different artists, mostly British, are represented, among them key sporting and animal artists such as John Frederick Herring, Sr. (1795–1865) and Harry Hall (1814–1882), and Royal Academicians James Ward (1769–1859) and Sir Alfred Munnings (1878–1959), the latter who served as President of the Royal Academy. Works in the exhibit feature images of racing, pets, hunting, and prized livestock including cattle and, especially, horses. -

Quarterdeck MARITIME LITERATURE & ART REVIEW

Quarterdeck MARITIME LITERATURE & ART REVIEW AUTUMN 2020 Compliments of McBooks Press MARITIME ART British Marine Watercolors A brief guide for collectors PD - Art BY JAMES MITCHELL All images courtesy of John Mitchell Fine Paintings in London ABOVE Detail from “A Frig- James Mitchell is the co-proprietor of John Mitchell ate and a Yacht becalmed Fine Paintings which has been associated with tradi- in the Solent,” oil on can- tional British and European paintings for ninety years. vas, 25” x 29”, by English marine artist Charles With a gallery just off Brook Street in the heart of Lon- Brooking (1723-1759). don’s Mayfair, the business is now run by James and William Mitchell, the grandsons of John Mitchell who began the dealership in 1931, and their colleague James Astley Birtwistle. ver the centuries, “the silver sea,” of which Shakespeare wrote, shaped Britain’s island home and deepest identity. Britons, many Obelieved, had saltwater running in their veins. However, in modern Britain, our extraordi- nary history as a seafaring nation is not nearly as familiar as it once was. The great Age of Sail has become the esoteric province of historians and enthusiasts sustained by regular doses of Quar- terdeck and the latest gripping novels of our fa- collectors of pictures from the same period. vorite naval authors. Once-acclaimed sea painters – Brooking, Similarly, English marine painting no longer Serres, Cleveley, Swaine, Pocock, among others receives the attention it deserves, and its subject – aren’t a common currency in the way they matter thought too specialized, even among were, say, half a century ago. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell Now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society

Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005 Page 1 of 6 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society Matthew H. Kaufman Professor of Anatomy, Honorary Librarian of the Royal Medical Society Abstract The two earliest diplomas in the possession of the Royal Medical Society were both awarded to George Joseph Bell, BA Oxford. One of these diplomas was his Extraordinary Membership Diploma that was awarded to him on 5 April 1839. Very few of these Diplomas appear to have survived, and the critical introductory part of his Diploma is inscribed as follows: Ingenuus ornatissimusque Vir Georgius Jos. Bell dum socius nobis per tres annos interfuit, plurima eademque pulcherrima, hand minus ingenii f elicis, quam diligentiae insignis, animique ad optimum quodque parati, exempla in medium protulit. In quorum fidem has literas, meritis tantum concessus, manibus nostris sigilloque munitas, discedenti lubentissime donatus.2 Edinburgi 5 Aprilis 1839.3 Copyright Royal Medical Society. All rights reserved. The copyright is retained by the author and the Royal Medical Society, except where explicitly otherwise stated. Scans have been produced by the Digital Imaging Unit at Edinburgh University Library. Res Medica is supported by the University of Edinburgh’s Journal Hosting Service url: http://journals.ed.ac.uk ISSN: 2051-7580 (Online) ISSN: ISSN 0482-3206 (Print) Res Medica is published by the Royal Medical Society, 5/5 Bristo Square, Edinburgh, EH8 9AL Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005: 39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Kaufman, M. H, Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society, Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2 2005, pp.39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society MATTHEW H. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

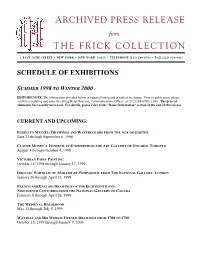

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SUMMER 1998 TO WINTER 2000 EDITORS NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm scheduling and dates by calling Heidi Rosenau, Communications Officer, at (212) 288-0700, x 264. The price of admission has recently increased. For details, please refer to the “Basic Information” section at the end of this release. CURRENT AND UPCOMING: FUSELI TO MENZEL: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLORS FROM THE AGE OF GOETHE June 23 through September 6, 1998 CLAUDE MONET’S VÉTHEUIL IN SUMMER FROM THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO, TORONTO August 4 through October 4, 1998 VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 DROUAIS’ PORTRAIT OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON January 26 through April 25, 1999 FRENCH AND ENGLISH DRAWINGS OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA February 8 through April 26, 1999 THE MEDIEVAL HOUSEBOOK May 11 through July 5, 1999 WATTEAU AND HIS WORLD: FRENCH DRAWINGS FROM 1700 TO 1750 October 18, 1999 through January 9, 2000 UPCOMING: VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Critically and commercially popular during the 19th century was the intriguing and distinctly British genre of Victorian fairy painting, the subject of an exhibition that comes this fall to The Frick Collection. The paintings and works on paper, roughly thirty in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from a comprehensive touring exhibition – the first of its type for this subject. -

Bell's Palsy Before Bell

Otology & Neurotology 26:1235–1238 Ó 2005, Otology & Neurotology, Inc. Bell’s Palsy Before Bell: Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel’s Observation of Bell’s Palsy in 1683 *Robert C. van de Graaf and †Jean-Philippe A. Nicolai *Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands, and †Department of Plastic Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, The Netherlands Bell’s palsy is named after Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842), Bell is limited to a few documents, it is interesting to discuss who has long been considered to be the first to describe Stalpart van der Wiel’s description and determine its additional idiopathic facial paralysis in the early 19th century. However, value for the history of Bell’s palsy. It is concluded that it was discovered that Nicolaus Anton Friedreich (1761–1836) Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel was the first to record Bell’s and James Douglas (1675–1742) preceded him in the 18th palsy in 1683. His manuscript provides clues for future century. Recently, an even earlier account of Bell’s palsy was historical research. Key Words: Bell’s Palsy—History—Facial found, as observed by Cornelis Stalpart van der Wiel (1620– Paralysis—Facial Nerve—Stalpart van der Wiel—Sir Charles 1702) from The Hague, The Netherlands in 1683. Because Bell—Facial nerve surgery. our current knowledge of the history of Bell’s palsy before Otol Neurotol 26:1235–1238, 2005. ‘‘Early in the winter of 1683.the housewife of notes of the physician James Douglas (1675–1742) from Verboom, shoemaker in The Hague.went to church to London (5,6). -

Chapter Eleven

Chapter eleven he greater opportunities for patronage and artistic fame that London could offer lured many Irish artists to seek their fortune. Among landscape painters, George Barret was a founding Tmember of the Royal Academy; Robert Carver pursued a successful career painting scenery for the London theatres and was elected President of the Society of Artists while, even closer to home, Roberts’s master George Mullins relocated to London in 1770, a year after his pupil had set up on his own in Dublin – there may even have been some connection between the two events. The attrac- tions of London for a young Irish artist were manifold. The city offered potential access to ever more elevated circles of patronage and the chance to study the great collections of old masters. Even more fundamental was the febrile artistic atmosphere that the creation of the Royal Academy had engen- dered; it was an exciting time to be a young ambitious artist in London. By contrast, on his arrival in Dublin in 1781, the architect James Gandon was dismissive of the local job prospects: ‘The polite arts, or their professors, can obtain little notice and less encouragement amidst such conflicting selfish- ness’, a situation which had led ‘many of the highly gifted natives...[to] seek for personal encourage- ment and celebrity in England’.1 Balancing this, however, Roberts may have judged the market for landscape painting in London to be adequately supplied. In 1769, Thomas Jones, himself at an early stage at his career, surveyed the scene: ‘There was Lambert, & Wilson, & Zuccarelli, & Gainsborough, & Barret, & Richards, & Marlow in full possession of landscape business’.2 Jones concluded that ‘to push through such a phalanx required great talents, great exertions, and above all great interest’.3 As well as the number of established practitioners in the field there was also the question of demand. -

Prolegomena to Pastels & Pastellists

Prolegomena to Pastels & pastellists NEIL JEFFARES Prolegomena to Pastels & pastellists Published online from 2016 Citation: http://www.pastellists.com/misc/prolegomena.pdf, updated 10 August 2021 www.pastellists.com – © Neil Jeffares – all rights reserved 1 updated 10 August 2021 Prolegomena to Pastels & pastellists www.pastellists.com – © Neil Jeffares – all rights reserved 2 updated 10 August 2021 Prolegomena to Pastels & pastellists CONTENTS I. FOREWORD 5 II. THE WORD 7 III. TREATISES 11 IV. THE OBJECT 14 V. CONSERVATION AND TRANSPORT TODAY 51 VI. PASTELLISTS AT WORK 71 VII. THE INSTITUTIONS 80 VIII. EARLY EXHIBITIONS, PATRONAGE AND COLLECTIONS 94 IX. THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF PASTEL PORTRAITS 101 X. NON-PORTRAIT SUBJECTS 109 XI. PRICES AND PAYMENT 110 XII. COLLECTING AND CRITICAL FORTUNE POST 1800 114 XIII. PRICES POST 1800 125 XIV. HISTORICO-GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY 128 www.pastellists.com – © Neil Jeffares – all rights reserved 3 updated 10 August 2021 Prolegomena to Pastels & pastellists I. FOREWORD ASTEL IS IN ESSENCE powdered colour rubbed into paper without a liquid vehicle – a process succinctly described in 1760 by the French amateur engraver Claude-Henri Watelet (himself the subject of a portrait by La Tour): P Les crayons mis en poudre imitent les couleurs, Que dans un teint parfait offre l’éclat des fleurs. Sans pinceau le doigt seul place et fond chaque teinte; Le duvet du papier en conserve l’empreinte; Un crystal la défend; ainsi, de la beauté Le Pastel a l’éclat et la fragilité.1 It is at once line and colour – a sort of synthesis of the traditional opposition that had been debated vigorously by theoreticians such as Roger de Piles in the previous century.