Education and Innovation: Key to Sustaining Lake Winnipeg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Lake Winnipeg

Great Plains Lakes The State of Lake Winnipeg Elaine Page and Lucie Lévesque An Overview of Nutrients and Algae t nearly 25,000 square kilometers, Lake Winnipeg (Manitoba, Canada) is the tenth-largest freshwater lake Ain the world and the sixth-largest lake in Canada by surface area (Figure 1). Lake Winnipeg is the largest of the three great lakes in the Province of Manitoba and is a prominent water feature on the landscape. Despite its large surface area, Lake Winnipeg is unique among the world’s largest lakes because it is comparatively shallow, with a mean depth of only 12 meters. Lake Winnipeg consists of a large, deeper north basin and a smaller, relatively shallow south basin. The watershed is the second-largest in Canada encompassing almost 1 million square kilometers, and much of the land in the watershed is cropland and pastureland for agricultural production. The lake sustains a productive commercial and recreational fishery, with walleye being the most commercially important species in the lake. The lake is also of great recreational value to the many permanent and seasonal communities along the shoreline. The lake is also a primary drinking water source for several communities around the lake. Although Lake Winnipeg is naturally productive, the lake has experienced accelerated nutrient enrichment over the past several decades. Nutrient concentrations are increasing in the major tributaries that flow into Lake Winnipeg (Jones and Armstrong 2001) and algal blooms have been increasing in frequency and extent on the lake, with the most noticeable changes occurring since the mid 1990s. Surface blooms of cyanobacteria have, in some years, covered greater than 10,000 square kilometers of the north basin of the lake Figure 1. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

Minnesota Red River Trails

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No, 7024-0078 (Jan 1987) ' ^ n >. •• ' M United States Department of the Interior j ; j */i i~i U i_J National Park Service National Register of Historic Places 41990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_______________________________________ Minnesota Red River Trails B. Associated Historic Contexts Minnesota Red River Trails, 1835-1871 C. Geographical Data State of Minnesota I | See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the Nal ional Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National R< gister documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related ^fo^r^e&-^r\^^r(l \feith the Natii nal Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirerrlents^eftirfn in 36 GnWFari 6Q~ tftd-the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. rJ it fft> Sigriature or certifying official I an R. Stewart Date / / __________________Deputy State-Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau ,,. , , Minnesota Historical Society 1, herebAcertify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Clean Water Guide

Clean water. For me. For you. Forever. A hands-on guide to keeping Manitoba’s water clean and healthy. WaterManitoba’s natural treasure Water is Manitoba’s most precious and essential resource. Where the water fl ows Our deep, pristine lakes give us drinking water. As well, our lakes Water is contained in natural geographic regions called watersheds. are beautiful recreation spots enjoyed by thousands of campers, Think of them as large bowls. Sometimes they are grouped together cottagers and fi shers — including many fi shers who earn their living to form larger regions, sometimes they are small and isolated. on our lakes. Watersheds help us protect our water by allowing us to control the spread of pollutants and foreign species from one watershed to Manitoba’s lakes, rivers and wetlands are home to a wide variety another. When we see Manitoba as a network of watersheds, it helps us of fi sh and wildlife. And our rushing rivers generate power for our to understand how actions in one area can affect water in other areas. businesses and light up our homes. Even more important, water is the source Where the water meets the land of all life on earth. It touches every area The strip of land alongside rivers, lakes, streams, dugouts, ponds of our lives. Without it, we could not and even man-made ditches is called a riparian zone or shoreline. thrive — we could not even survive. The trees and vegetation along this strip of land are an important habitat for many kinds of wildlife and the last line of defense between Unfortunately, many of the things pollutants in the ground and our water. -

Red River Trails

Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau ------... ----,. I' , I 1 /7 Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau Compliments of the Great Northern Railway The Red River of the North Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau Foreword There is a certain hay meadow in southwestern Minnesota; curiously enough this low-lying bit of prairie, often entirely submerged, happens to be an important height of land dividing the great water sheds of Hudson's Bay and Mississippi riv,er. I t lies between two lakes: One of these, the Big Stone, gives rise to the Minnesota river, whose waters slide down the long tobog gan of the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf of Mexico; from the other, Lake Traverse, flows the Bois de Sioux, a main tributary of the Red River of the North, which descends for over five. hundred miles through one of the richest valleys in the world to Lake Winnipeg and eventually to Hudson's Bay. In the dim geologic past, the melting of a great glacier ground up limestone and covered this valley with fertile deposits, while the glacial Lake Agassiz subsequently levelled it to a vast flat plain. Occasionally in spring when the rivers are exceptionally high, the meadow is flooded and becomes a lake. Then a boatman, travelling southward from the semi-arctic Hudson's Bay, could float over the divide and reach the Gulf of Mexico entirely by water route. The early travellers gave, romantic names to the rive.rs of the West, none more so, it seems to me, than Red River of the North, 3 with its lonely cadence, its suggestion of evening and the cry of wild birds in far off quiet places. -

2.0 Native Land Use - Historical Period

2.0 NATIVE LAND USE - HISTORICAL PERIOD The first French explorers arrived in the Red River valley during the early 1730s. Their travels and encounters with the aboriginal populations were recorded in diaries and plotted on maps, and with that, recorded history began for the region known now as the Lake Winnipeg and Red River basins. Native Movements Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye records that there were three distinct groups present in this region during the 1730s and 1740s: the Cree, the Assiniboine, and the Sioux. The Cree were largely occupying the boreal forest areas of what is now northern and central Manitoba. The Assiniboine were living and hunting along the parkland transitional zone, particularly the ‘lower’ Red River and Assiniboine River valleys. The Sioux lived on the open plains in the region of the upper Red River valley, and west of the Red River in upper reaches of the Mississippi water system. Approximately 75 years later, when the first contingent of Selkirk Settlers arrived in 1812, the Assiniboine had completely vacated eastern Manitoba and moved off to the west and southwest, allowing the Ojibwa, or Saulteaux, to move in from the Lake of the Woods and Lake Superior regions. Farther to the south in the United States, the Ojibwa or Chippewa also had migrated westward, and had settled in the Red Lake region of what is now north central Minnesota. By this time some of the Sioux had given up the wooded eastern portions of their territory and dwelt exclusively on the open prairie west of the Red and south of the Pembina River. -

Cec-Decision-Pimicikamak.Pdf

The Manitoba Clean Environment Commission Pimicikamak Cree Nation Motion Respecting: The Wuskwatim Generation and Transmission Project Background In April 2003, Manitoba Hydro (“Hydro”) and the Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation (“NCN”) filed Environmental Impact Statements and the Justification, Need for and Alternatives to the proposed Wuskwatim Generation Project with the Manitoba Clean Environment Commission (“CEC”). Also, in April 2003 Hydro filed Environmental Impact Statements and the Justification, Need for and Alternatives to the proposed Wuskwatim Transmission Project with the CEC. These two filings constitute (“the Filing”). On August 28, 2003, the CEC set out a Preliminary Pre-Hearing Schedule to conduct a review of the Filing which provides an opportunity for all interested parties to submit information requests, file evidence prior to the hearing, conduct cross examination, and submit final argument at the hearing. On July 28, 2003, the CEC received a motion from the Pimicikamak Cree Nation (“PCN”) regarding the Filing. In addition to accepting written responses to the PCN motion from Hydro and NCN, the CEC received written comments from other interested parties and held a hearing on September 30, 2003 to listen to oral argument regarding the PCN motion. Oral and written submissions were provided by PCN, Hydro, NCN, the Association for the Displaced Residents of South Indian Lake (“DRSIL”), the Boreal Forest Network (“BFN”), the Canadian Nature Federation (“CNF”), the Community Association of South Indian Lake (“CASIL”), the Consumers Association of Canada/Manitoba Society of Seniors (“CAC/MSOS”), the O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation (“OCN”), the Tataskweyak Cree Nation (“TCN”), Time to Respect Earth’s Ecosystem/Resource Conservation Manitoba (“TREE/RCM”), Trapline #18, and Manitoba Conservation. -

Appendix 1. Details Regarding Historical and Current Colonial Waterbird Surveys on the Large Lakes of Southern Manitoba, Canada

Appendix 1. Details regarding historical and current colonial waterbird surveys on the large lakes of southern Manitoba, Canada. Table A1.1. Colonial waterbird surveys conducted between 1969 and 2017 in southern Manitoba. Details include survey dates when available, the portion of the region surveyed (where ‘Whole region’ = Lake Winnipeg, Lake Winnipegosis, Lake Manitoba, and the Interlake region), survey method when available (where ‘Aerial’ = fixed wing, helicopter, or a combination; ‘Boat’ = counts made from a boat; ‘Ground’ = counts made within the colony; or a combination), and species included in the survey. Year Dates Area surveyed Survey method Species Reference 1969 “when the eggs Whole region Aerial (visual)/ DCCO, Vermeer 1969, 1970a started to hatch” Ground AWPE 1970 24 June Lake Winnipegosis† Ground CATE Vermeer 1970b 1979 11, 12, 19 June Whole region Aerial (visual)/ All species Koonz and Rakowski Ground 1985 1986 NA Whole region NA CATE B. Koonz, cited in Wires and Cuthbert 2000 1987 Late June Lake Winnipegosis Boat/Ground DCCO Hobson et al. 1989 1989-92 NA Whole region NA CATE B. Koonz, cited in Wires and Cuthbert 2000 1990 NA Lake Winnipeg, Lake NA COTE Manitoba Conservation, Manitoba, Inter-lake as cited in Wilson et al. region 2014 1999 4-11 June Lake Winnipegosis Boat/Ground All species Koonz 2000 2012 13, 15, 16 June Whole region Aerial (photography) All species Wilson et al. 2014 2017 11, 12, 19, 20 June Whole region Aerial (photography) All species Current study †Surveys were also conducted at several colonies on Lake Winnipeg, but these were not included in our analysis LITERATURE CITED Hobson, K. -

RED RIVER a Canadian Heritage River Ten-Year Monitoring Report: 2007 – 2017

RED RIVER A Canadian Heritage River Ten-year Monitoring Report: 2007 – 2017 Prepared by Manitoba Sustainable Development Parks and Protected Spaces Branch for The Canadian Heritage Rivers Board April 2018 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by Manitoba Sustainable Development, with contributions from numerous individuals and organizations. Special thanks goes to Anne-Marie Thibert, outgoing Executive Director of Rivers West - Red River Corridor Association Inc., who provided photos and other input for the report. Manitoba Sustainable Development would also like to acknowledge the work of Rivers West and its partner organizations over the past ten years, and all they did to recognize, promote and sustain the Red River’s cultural heritage, natural heritage and recreational values over the first decade of the river’s designation to the Canadian Heritage Rivers System. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Over the course of thousands of years, the Red of channel migration and erosion. Riverbank River played a significant role, first in the lives of stabilization projects have been undertaken in Indigenous Peoples and subsequently, in the growth certain areas to address some issues with erosion. and development of Western Canada. It has been The identification of zebra mussels, an invasive the site of numerous historical and cultural events, species, in the Red River in 2015 is cause for while also providing recreational opportunities concern, but to date has not resulted in any and having a considerable influence on the area’s measurable impacts to the ecosystem or river-based natural landscape. On the basis of its strong cultural infrastructure. heritage values, the Red River was designated to the Canadian Heritage Rivers System (CHRS) in The management plan for the Red River was 2007. -

Abundance, Population Trends, and Negative Associations with Lake Water Levels for Six Colonial Waterbird Species Over Five Decades in Southern Manitoba

VOLUME 16, ISSUE 1, ARTICLE 7 McKellar, A. E., S. E. Simpson, and S. Wilson. 2021. Abundance, population trends, and negative associations with lake water levels for six colonial waterbird species over five decades in southern Manitoba. Avian Conservation and Ecology 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01789-160107 Copyright © 2021 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Research Paper Abundance, population trends, and negative associations with lake water levels for six colonial waterbird species over five decades in southern Manitoba Ann E. McKellar 1 , Steven E. Simpson 2 and Scott Wilson 3,4 1Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, Government of British Columbia, Canada, 3Wildlife Research Division, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 4Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, University of British Columbia, Canada ABSTRACT. Management of colonial waterbirds at regional, national, and continental scales requires up-to-date monitoring information on breeding locations, population sizes, and trends. The large lakes of southern Manitoba, Canada (Winnipeg, Winnipegosis, and Manitoba), and the inter-lake region host nationally and continentally significant populations of colonial waterbirds, but the area has been surveyed only irregularly in the past. We conducted surveys in 2017 to produce updated information on population abundance and trends for the six most abundant species breeding on the lakes: Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis), Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia), Common Tern (Sterna hirundo), Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), and American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos). We also examined the relationship between lake water levels and breeding pair abundance on Lake Winnipegosis. -

A Guide to Reviewing Minnesota's Draft Nutrient Reduction Strategy

www.pca.state.mn.us A Guide to Reviewing Minnesota’s Draft Nutrient Reduction Strategy How were the goals established? ................................................................................................................. 2 Why are milestones needed? ....................................................................................................................... 2 If we take actions to solely address local water quality impairments, will we be doing enough to protect downstream waters? .................................................................................................................................... 2 Is groundwater protection included? ........................................................................................................... 3 Have there been any recent nutrient reductions? ....................................................................................... 3 What will change in the state as a result of the Strategy? ........................................................................... 3 Are changes in local watershed planning proposed? ................................................................................... 4 How can BMP adoption be stepped up? ...................................................................................................... 4 Are new regulations proposed? .................................................................................................................... 5 Are cropping changes needed?.................................................................................................................... -

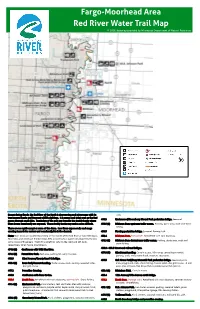

Fargo-Moorhead Area Red River Water Trail Map © 2020, Basemap Provided by Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Fargo-Moorhead Area Red River Water Trail Map © 2020, Basemap provided by Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Except during floods, the Red River of the North is slow-moving and picturesque with its trails. tree-covered banks and frequent wildlife sightings. It is serene and quiet even as the Red 460.3 Lindenwood/Gooseberry Mound Park pedestrian bridge. Seasonal. passes through small cities. Reminders of the past are found in the muddy banks where bison bones occasionally are exposed. These muddy banks may make access difficult. 458.5 (L) Midtown Dam upstream trailer access. Parking, picnic area, dock and shore fishing. There are no rapids except at some of the dams. Low flows expose rocks and snags creating hazards for motors and occasionally block the channel. 458.5 Floating pedestrian bridge. Seasonal. Portage Left. Note: River miles are counted beginning at the mouth of the Red River at Lake Winnipeg, 458.4 Midtown Dam. Portage left. Retrofitted with rock slopeway. Manitoba, and ending at Breckenridge, MN, according to a system developed by the U.S. 458.3 (L) Midtown Dam downstream trailer access. Parking, picnic area, dock and Army Corps of Engineers. Right (R) and left (L) refer to the right and left bank, shore fishing. respectively, when facing downstream. 458.0 - 457.5 Street and railroad bridges. 476.8 (L) Confluence with Wild Rice River. 457.8 (R) Hjemkomst Landing. Carry-in access, ADA ramp, canoe/kayak rental, 473.5 (L) Forest River Park. Rest area, parking lot, carry-in access. parking, trails, interpretive kiosk, museum, restrooms. 468.5 52nd Avenue/County Road 12 bridge.