Zebra Mussels 101

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zebra Mussels Georgia Is Home to Several Species of Mussels, but Thankfully Zebra Mussels Currently Are Not One of Them

Zebra Mussels Georgia is home to several species of mussels, but thankfully zebra mussels currently are not one of them. A small mollusk having “zebra” stripes, it has spread throughout the country and has been described by the USGS as the “poster child of biological invasions”. In areas where it becomes established it can pose significant negative Photo: A Benson - USGS ecological and economic impacts through biofouling and outcompeting native species. Discoveries of Zebra Mussels Zebra Mussel Identification Though zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) have been found in several states since their introduction via ballast water into the Great Lakes, the species has thus far not been found in Georgia. Zebra mussels can be confused with other mussel species, particularly the non-native quagga mussel (Dreissena bugensis). The guide below can help further distinguish the species. Should you have questions regarding identification of a mussel you have found, or if you suspect you have found a zebra mussel, RETAIN THE SPECIMEN and IMMEDIATELY contact your regional Georgia DNR Wildlife Resources Division Fisheries Office. Source: USGS https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/factsheet.aspx?speciesid=5 So, What Harm do Zebra Mussels Cause? A notorious mussel introduced into the Great Lakes via ballast water a few decades ago, zebra mussels have since spread to several states throughout the U.S. Though small in size, the mussel has been known to cause enormous-sized problems, most notably its biofouling capabilities that often result in clogged water lines for power plants, industrial facilities, and other commercial entities. Such biofouling has resulted in significant economic costs to several communities. -

The State of Lake Winnipeg

Great Plains Lakes The State of Lake Winnipeg Elaine Page and Lucie Lévesque An Overview of Nutrients and Algae t nearly 25,000 square kilometers, Lake Winnipeg (Manitoba, Canada) is the tenth-largest freshwater lake Ain the world and the sixth-largest lake in Canada by surface area (Figure 1). Lake Winnipeg is the largest of the three great lakes in the Province of Manitoba and is a prominent water feature on the landscape. Despite its large surface area, Lake Winnipeg is unique among the world’s largest lakes because it is comparatively shallow, with a mean depth of only 12 meters. Lake Winnipeg consists of a large, deeper north basin and a smaller, relatively shallow south basin. The watershed is the second-largest in Canada encompassing almost 1 million square kilometers, and much of the land in the watershed is cropland and pastureland for agricultural production. The lake sustains a productive commercial and recreational fishery, with walleye being the most commercially important species in the lake. The lake is also of great recreational value to the many permanent and seasonal communities along the shoreline. The lake is also a primary drinking water source for several communities around the lake. Although Lake Winnipeg is naturally productive, the lake has experienced accelerated nutrient enrichment over the past several decades. Nutrient concentrations are increasing in the major tributaries that flow into Lake Winnipeg (Jones and Armstrong 2001) and algal blooms have been increasing in frequency and extent on the lake, with the most noticeable changes occurring since the mid 1990s. Surface blooms of cyanobacteria have, in some years, covered greater than 10,000 square kilometers of the north basin of the lake Figure 1. -

Risk Assessment for Three Dreissenid Mussels (Dreissena Polymorpha, Dreissena Rostriformis Bugensis, and Mytilopsis Leucophaeata) in Canadian Freshwater Ecosystems

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2012/174 Document de recherche 2012/174 National Capital Region Région de la capitale nationale Risk Assessment for Three Dreissenid Évaluation des risques posés par trois Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha, espèces de moules dreissénidées Dreissena rostriformis bugensis, and (Dreissena polymorpha, Dreissena Mytilopsis leucophaeata) in Canadian rostriformis bugensis et Mytilopsis Freshwater Ecosystems leucophaeata) dans les écosystèmes d'eau douce au Canada Thomas W. Therriault1, Andrea M. Weise2, Scott N. Higgins3, Yinuo Guo1*, and Johannie Duhaime4 Fisheries & Oceans Canada 1Pacific Biological Station 3190 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo, BC V9T 6N7 2Institut Maurice-Lamontagne 850 route de la Mer, Mont-Joli, QC G5H 3Z48 3Freshwater Institute 501 University Drive, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 4Great Lakes Laboratory for Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 867 Lakeshore Road, PO Box 5050, Burlington, Ontario L7R 4A6 * YMCA Youth Intern This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et des Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle traite des day in the time frames required and the problèmes courants selon les échéanciers dictés. documents it contains are not intended as Les documents qu‟elle contient ne doivent pas être definitive statements on the subjects addressed considérés comme des énoncés définitifs sur les but rather as progress reports on ongoing sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports investigations. d‟étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans la language in which they are provided to the langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit envoyé au Secretariat. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

Minnesota Red River Trails

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No, 7024-0078 (Jan 1987) ' ^ n >. •• ' M United States Department of the Interior j ; j */i i~i U i_J National Park Service National Register of Historic Places 41990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_______________________________________ Minnesota Red River Trails B. Associated Historic Contexts Minnesota Red River Trails, 1835-1871 C. Geographical Data State of Minnesota I | See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the Nal ional Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National R< gister documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related ^fo^r^e&-^r\^^r(l \feith the Natii nal Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirerrlents^eftirfn in 36 GnWFari 6Q~ tftd-the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. rJ it fft> Sigriature or certifying official I an R. Stewart Date / / __________________Deputy State-Historic Preservation Officer State or Federal agency and bureau ,,. , , Minnesota Historical Society 1, herebAcertify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Quagga/Zebra Mussel Control Strategies Workshop April 2008

QUAGGA AND ZEBRA MUSSEL CONTROL STRATEGIES WORKSHOP CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................v BACKGROUND .............................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW AND OBJECTIVE ....................................................................................................4 WORKSHOP ORGANIZATION ....................................................................................................5 LOCATION ...................................................................................................................................10 WORKSHOP PROCEEDINGS – THURSDAY, APRIL 3, 2008 ................................................10 AwwaRF Welcome ............................................................................................................10 Introductions, Logistics, and Workshop Objectives ..........................................................11 Expert #1 - Background on Quagga/Zebra Mussels in the West .......................................11 Expert #2 - Control and Disinfection - Optimizing Chemical Disinfections.....................12 Expert #3 - Control and Disinfection .................................................................................13 Expert #4 - Freshwater Bivalve Infestations; -

RAPID RESPONSE PLAN for the ZEBRA MUSSEL (Dreissena Polymorpha) in MASSACHUSETTS

RAPID RESPONSE PLAN FOR THE ZEBRA MUSSEL (Dreissena polymorpha) IN MASSACHUSETTS Prepared for the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation 251 Causeway Street, Suite 700 Boston, MA 02114-2104 Prepared by ENSR 2 Technology Park Drive Westford, MA 01886 June 2005 RAPID RESPONSE PLAN FOR THE ZEBRA MUSSEL (Dreissena polymorpha) IN MASSACHUSETTS Species Taxonomy and Identification....................................................................................................1 Species Origin and Geography..............................................................................................................1 Species Ecology.....................................................................................................................................2 Detection of Invasion .............................................................................................................................3 Species Confirmation.............................................................................................................................4 Quantifying the Extent of Invasion.........................................................................................................4 Species Threat Summary ......................................................................................................................5 Communication and Education..............................................................................................................5 Quarantine Options................................................................................................................................7 -

Zebra Mussels As Ecosystem Engineers: Their Contribution to Habitat Structure and Influences on Benthic Gastropods

ZEBRA MUSSELS AS ECOSYSTEM ENGINEERS: THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO HABITAT STRUCTURE AND INFLUENCES ON BENTHIC GASTROPODS NIRVANI PERSAUD Marist College, Poughkeepsie, NY 12601 USA MENTOR SCIENTIST: DR. JORGE GUTIERREZ Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, NY 12545 USA Abstract. In this study, the fractal properties of zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha, beds and the size and abundance of co-occurring gastropods were assessed. Data collected support the hypothesis that zebra mussels increase the roughness of intertidal bedrock. An analysis of plaster casts, made from rocks removed from Norrie Point (Hudson River, river mile 86), showed that the fractal dimension (FD) of the rocky substrates significantly decreases if mussels are removed (mussel covered rock mean FD: 1.43, bare rock mean FD:1.26). Fractal dimension values obtained from rocks with zebra mussels ranged between 1.03 and 1.52. However, variation in the size and density of snails did not correlate with the fractal dimension of these rocks. Further investigation comparing snail colonization rates in rocks with and without zebra mussels (or structural mimics) will help to elucidate whether modification of the fractal properties of the rocky substrate by ecosystem engineers affect gastropod abundance and distribution. INTRODUCTION Ecosystem engineers are defined as organisms that control the availability of resources to other organisms by causing physical state changes in biotic or abiotic materials (Jones et al. 1994, 1997). Many exotic species engineer the environment by altering its three-dimensional structure and, thus, the magnitude of a variety of resource flows (Crooks 2002). Aquatic mollusks are particularly important as engineers because of their ability to produce shells that often occur at high densities and persist over for long times (Gutiérrez et al. -

Zebra and Quagga Mussels

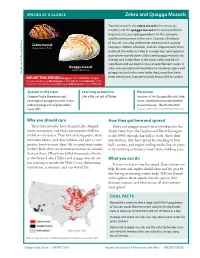

SPECIES AT A GLANCE Zebra and Quagga Mussels Two tiny mussels, the zebra mussel (Dreissena poly- morpha) and the quagga mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis), are causing big problems for the economy and the environment in the west. Colonies of millions of mussels can clog underwater infrastructure, costing Zebra mussel (Actual size is 1.5 cm) taxpayers millions of dollars, and can strip nutrients from nearly all the water in a lake in a single day, turning entire ecosystems upside down. Zebra and quagga mussels are already well established in the Great Lakes and Missis- sippi Basin and are beginning to invade Western states. It Quagga mussel takes only one contaminated boat to introduce zebra and (Actual size is 2 cm) quagga mussels into a new watershed; once they have Amy Benson, U.S. Geological Survey Geological Benson, U.S. Amy been introduced, they are virtually impossible to control. REPORT THIS SPECIES! Oregon: 1-866-INVADER or Oregon InvasivesHotline.org; Washington: 1-888-WDFW-AIS; California: 1-916- 651-8797 or email [email protected]; Other states: 1-877-STOP-ANS. Species in the news Learning extensions Resources Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Like a Mussel out of Water Invasion of the Quagga Mussels! slide coverage of quagga mussels: www. show: waterbase.uwm.edu/media/ opb.org/programs/ofg/episodes/ cruise/invasion_files/frame.html view/1901 (Only viewable with Microsoft Internet Explorer) Why you should care How they got here and spread These tiny invaders have dramatically changed Zebra and quagga mussels were introduced to the entire ecosystems, and they cost taxpayers billions Great Lakes from the Caspian and Black Sea region of dollars every year. -

Zebra Mussel (Dreissena Polymorpha (Pallas, 1771)

Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas, 1771) The zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha, was originally described by the famous Russian scientist and explorer Pyotr Simon Pallas from a population in a tributary of the Ural River in the Caspian Sea Basin (Pallas 1771). The common name of these mussels is derived from the zebra-like stripes on their shells. Once adult mussels (sexually mature) are attached to a substrate by their byssal threads, they generally remain there for life; this is particularly true for larger mussels. Aided by the expansion of commercial boat traffic through newly constructed canals, this species spread west from Russia into most of Europe during the 19th century. Zebra mussels were found for the first time in North America in 1988 in Lake St. Clair - the waterbody connecting Lake Huron with Lake Erie (Hebert et al. 1989). Estimated to be 2-3 years old, they were likely transported there as planktonic (i.e., floating) larvae or as attached juveniles or adults in the freshwater ballast of a transatlantic ship. Since their introduction, zebra mussels have spread throughout all the Great Lakes, the Hudson, Ohio, Illinois, Tennessee, Mississippi and Arkansas rivers, as well as other streams, lakes and rivers, which altogether cross 21 states and the provinces of Quebec and Ontario. The zebra mussel has become the most serious non-indigenous biofouling pest ever to be introduced into North American freshwater systems. It has the ability to tolerate a wide range of conditions and is extremely adaptable. It has the potential to significantly alter the ecosystem in any body of water it inhabits. -

Clean Water Guide

Clean water. For me. For you. Forever. A hands-on guide to keeping Manitoba’s water clean and healthy. WaterManitoba’s natural treasure Water is Manitoba’s most precious and essential resource. Where the water fl ows Our deep, pristine lakes give us drinking water. As well, our lakes Water is contained in natural geographic regions called watersheds. are beautiful recreation spots enjoyed by thousands of campers, Think of them as large bowls. Sometimes they are grouped together cottagers and fi shers — including many fi shers who earn their living to form larger regions, sometimes they are small and isolated. on our lakes. Watersheds help us protect our water by allowing us to control the spread of pollutants and foreign species from one watershed to Manitoba’s lakes, rivers and wetlands are home to a wide variety another. When we see Manitoba as a network of watersheds, it helps us of fi sh and wildlife. And our rushing rivers generate power for our to understand how actions in one area can affect water in other areas. businesses and light up our homes. Even more important, water is the source Where the water meets the land of all life on earth. It touches every area The strip of land alongside rivers, lakes, streams, dugouts, ponds of our lives. Without it, we could not and even man-made ditches is called a riparian zone or shoreline. thrive — we could not even survive. The trees and vegetation along this strip of land are an important habitat for many kinds of wildlife and the last line of defense between Unfortunately, many of the things pollutants in the ground and our water. -

Red River Trails

Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau ------... ----,. I' , I 1 /7 Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau Compliments of the Great Northern Railway The Red River of the North Red River Trails by Grace Flandrau Foreword There is a certain hay meadow in southwestern Minnesota; curiously enough this low-lying bit of prairie, often entirely submerged, happens to be an important height of land dividing the great water sheds of Hudson's Bay and Mississippi riv,er. I t lies between two lakes: One of these, the Big Stone, gives rise to the Minnesota river, whose waters slide down the long tobog gan of the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf of Mexico; from the other, Lake Traverse, flows the Bois de Sioux, a main tributary of the Red River of the North, which descends for over five. hundred miles through one of the richest valleys in the world to Lake Winnipeg and eventually to Hudson's Bay. In the dim geologic past, the melting of a great glacier ground up limestone and covered this valley with fertile deposits, while the glacial Lake Agassiz subsequently levelled it to a vast flat plain. Occasionally in spring when the rivers are exceptionally high, the meadow is flooded and becomes a lake. Then a boatman, travelling southward from the semi-arctic Hudson's Bay, could float over the divide and reach the Gulf of Mexico entirely by water route. The early travellers gave, romantic names to the rive.rs of the West, none more so, it seems to me, than Red River of the North, 3 with its lonely cadence, its suggestion of evening and the cry of wild birds in far off quiet places.