At Bede's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jarrow Booklet 2019.Cdr

Programme of events 1988 - 2019 Welcome to the 31st Jarrow Festival Since its revival by Jarrow Councillors in 1988, the Jarrow Festival has gone on from strength to strength celebrating art, culture, education, sport and leisure activities and I know that this year's festival will not disappoint. We remain a strong, vibrant and close community, which is why we believe it is important that we continue to celebrate the Jarrow Festival every year and we hope that everyone will come along and support the many events. This year the Festival Finale will be a “Parade of Banners” from the Town Hall to Drewett's Park bringing together communities, groups and organisations from across Jarrow and culminating in a celebration of all the charitable and volunteer organisations and local volunteers in Jarrow and across South Tyneside . I am sure that despite the difficulties many of the community organisations have had this year that Jarrow Festival 2019 will be one of the most successful and enjoyable yet, particularly if we are blessed with some good weather. Roy Merrin (Chair Person Jarrow Festival Committee) Cllr Ken Stephenson (Vice Chair and Mayor South Tyneside Council) The Jarrow Festival 2019 would like to thank....... South Tyneside Council Best Wishes from Bede Ward Councillors Fay Cunningham and Margaret Peacock hope everyone enjoys the fantastic events which are taking place at our “31st Anniversary” Jarrow Festival this year. Jarrow Hall Anglo Saxon Farm and Bede Museum will be open every day during Jarrow fesval week 10am – 4pm. There will be plenty for everyone to discover, learn and enjoy. -

Public Archaeology

Public Archaeology Arts of Engagement edited by Howard Williams Caroline Pudney Afnan Ezzeldin Access Archaeology aeopr ch es r s A A y c g c e o l s o s e A a r c Ah Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-373-7 ISBN 978-1-78969-374-4 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors Archaeopress 2019 Cover image: The Heritage Graffiti Project during creation (Photograph: Ryan Eddleston, reproduced with permission) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................................... vii Contributors.......................................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................x Foreword ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

EXARC Berlin 2020 Abstracts

#EXARCBerlin https://exarc.net/meetings/berlin #EXARCBERLIN 2020 Welcome Address by Pascale Barnes Hello, my name is Pascale Barnes and I am the current Chair of EXARC. For those of you not already familiar with EXARC, our organisation • Has been around since 2001 and has grown from very humble beginnings into the organisation that we are today – a vibrant, dynamic growing international cultural heritage network with over 350 members in over 40 countries. • Our MISSION is to make the archaeological past widely accessible and includes facilitating both research and education. • EXARC has 4 LEGS: Ancient & traditional Technology, Experimental Archaeology, Museum Practice and Interpretation & Education. • EXARC has 4 TARGET GROUPS: Museums, Higher Education Centres, Organisations and Individuals who are working in the fi elds connected with our 4 LEGS. • I am very proud to say that EXARC is an inclusive organisation. We are great example of how a society, based in academic research, has opened itself to a diverse range of members from professors of archaeology to professional craft speople, from historical interpreters to students of experimental archaeology. 2 #EXARCBERLIN 2020 • We are active within the world of museums, as an affi liated organisation with ICOM - the International Council of Museums and as a member of NEMO the Network of European Museum Organisations. • EXARC connects people – We organise several cooperation projects, such as our Fellowship with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, our own Twinning Programme and collaborate on various EU projects. • We host a variety of national and international events including Experimental Archaeology Conferences and specifi cally themed meetings, Which brings me to the reason why we have all gathered virtually today. -

Hello Tomorrow, Change Is Happening

South Tyneside HELLO TOMORROW, CHANGE IS HAPPENING 00 Your pathway to employment 09 Council services online 14 South Tyneside Festival 25 Raising standards for children 26 New school for Hebburn 38 Health and wellbeing A Sum mer P arade fairy v isits Th e Word's handcrafte d, replica Sulley June 2018 Brought to you in Partnership with: South Tyneside Delivering our promise Wheels set in motion for We continue to deliver against our promise to make South Tyneside a great place to live, work and bring up families. We are investing across the whole of South Tyneside in regeneration and infrastructure, housing, schools, parks, £21million interchange adult social care, skills, children and young people and many more areas that are important to you. Construction of the new £21million transport I’m proud to see that work has started on the new transport interchange for South Shields is underway. interchange in South Shields Town Centre as part of the £100million regeneration masterplan. This follows the Work has started on schedule centre and the development of successful completion of The Word, National Centre for the on the state-of-the-art new new public transport facilities, Written Word which continues to attract thousands more facility, which will bring together connectivity and a high quality visitors into the town centre - more than 600,000 people a modern bus station and sense of arrival will help to have visited The Word in the first 18 months. relocated Metro station. attract more people to South Shields for shopping and leisure. As part of our long-term investment in schools and our The interchange forms Phase ambition and investment in towns and neighbourhoods, Two of the £100million South The Council is working with a new school in Hebburn has recently received planning Shields 365 regeneration partners Muse Developments permission. -

AGENDA ITEM No

JARROW HALL EDUCATION VOLUNTEER JOB TITLE Education Volunteer REPORTS TO Programme Lead (Education) Lead Education Project Officer LOCATION Jarrow Hall, Church Bank, NE32 3DY WHY WE WANT YOU Jarrow Hall has an incredibly popular educational offer for School Visits. We usually have schools in most weeks and cater mostly for Key Stage Two offering sessions on Anglo-Saxon life and the life of St. Bede. We run for a full day with time on the farm and the Thirlings hall in the morning and then there is a choice of workshops in the afternoon. We also run sessions at St. Pauls’ Church should the school wish to select this option. The day is lead by the Education team with school staff also present. The Education team run the activities and engage with the children offering role plays, crafts and hands on activities. We would love to have volunteers who would like to help run these sessions, preparing resources, setting up and cleaning up after but also shadowing sessions, helping during, and depending upon knowledge and experience delivering to the class. All with support and guidance from staff. As a volunteer at Jarrow Hall you will be entitled to certain benefits in return for your time. As a key part of the team you will be expected to play a proactive and dynamic role alongside your fellow volunteers and staff to ensure that Jarrow Hall builds and maintains a reputation as one of the finest, most welcoming and best loved venues in the region and beyond. 1 IS THIS ROLE FOR YOU? As an Education Volunteer you have the opportunity to make sure that school children and their teachers have a memorable day learning all about Jarrow, the Anglo-Saxons and of course St. -

4267 LDF Cover St.Pauls 1.Indd

SOUTH TYNESIDE local development framework THE NEW DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR YOUR BOROUGH Final ADOPTED Version Supplementary Planning Document 13 St. Paul’s Conservation Area Management Plan August 2007 South Tyneside Local Development Framework – Family Tree National Planning Policy Regional Spatial Strategy for the North East (RSS) South Tyneside Community Strategy / Local Area Agreement SOUTH TYNESIDE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (LDF) South Tyneside Regeneration Strategy Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) Core Strategy Local Development Scheme (LDS) Site-Specific Development Control Area Action Plans (AAP) Supplementary Planning Documents (SPD) Allocations Policies Conservation Area Management Plans East & West Boldon Villages Sustainable Construction South Shields Town Centre & Waterfront Planning Obligations and Development & Agreements Cleadon Village Jarrow Town Centre & Bede’s World Urban Design Framework Parking Standards Whitburn Village Hebburn Town Centre Open Space Strategy Green Travel Affordable Housing Masterplans and Design Guides Annual Monitoring Report (AMR) The Statutory Development Plan Contents Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Aims of the Management Plan 1.3 The Development Plan Aerial Photograph Maps Panoramic Photographs Section 2 Statement of Significance, Key Issues/ Vulnerability and Actions 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Character Area 1: North River Don Character Area 2.3 Character Area 2: Parkland Character Area 2.4 Character Area 3: St. Paul’s Historic Core Special Character Area Section 3 Conservation Area and Historic Buildings Legislation and Guidance 3.1 Conservation Area and Historic Buildings Legislation 3.2 Requirements for Works To Historic Buildings and Scheduled Ancient Monuments 3.3 Guidance on Repairs, Alterations and Extensions 3.4 Guidance on Works to Streets, Landscape and Open Spaces 3.5 Design Quality Management Section 4 References and Further Reading Appendix 1 Statement of Consultation Appendix 2 Sustainability Appraisal Report South Tyneside Local Development Framework (Adopted) SPD 13: St. -

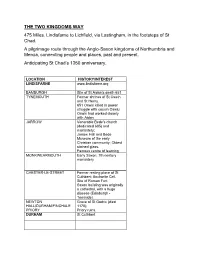

TKW Route Summary May 2021

THE TWO KINGDOMS WAY 475 Miles. Lindisfarne to Lichfield, via Lastingham, in the footsteps of St Chad. A pilgrimage route through the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Northumbria and Mercia, connecting people and places, past and present. Anticipating St Chad’s 1350 anniversary. LOCATION HISTORY/INTEREST LINDISFARNE www.lindisfarne.org BAMBURGH Site of St Aidan’s death 651 TYNEMOUTH Former shrines of St Oswin and St Henry. 651 Oswin killed in power struggle with cousin Oswiu Oswin had worked closely with Aidan JARROW Venerable Bede’s church (dedicated 685) and monastery; Jarrow Hall and Bede Museum of the early Christian community; Oldest stained glass. Famous centre of learning MONKWEARMOUTH Early Saxon, 7th century monastery CHESTER-LE-STREET Former resting place of St Cuthbert; Anchorite Cell. Site of Roman Fort. Saxon building was originally a cathedral, with a huge diocese (Edinburgh - Teesside) NEWTON Grave of St Godric (died HALL/DURHAM/FINCHALE 1170); PRIORY Priory ruins. DURHAM St Cuthbert HARTLEPOOL Hartlepool Abbey founded by Aidan c.640. Current site of St Hilda’s Church C12th. WHITBY Hilda’s monastery. Synod of Whitby 664AD LASTINGHAM Chad was Abbot YORK Chad was 2nd Abbot BEVERLEY “England’s grandest church” (1220 -1400) John of Beverley’s (640 – 721) grave and shrine. HUMBER BRIDGE BARTON-UPON-HUMBER Wulfhere also donated land sufficient for fifty families at a place in Lindsey, referred to by Bede as Ad Barwae. This is probably Barrow upon Humber: where an Anglo- Saxon monastery of a later date has been excavated. This was easily reached by river from the Midlands and close to an easy crossing of the River Humber, allowing rapid communication along surviving Roman roads with Lastingham. -

The Way of Learning

1 JARROW TO DURHAM Introduction This guide describes the pilgrimage route between St Paul’s Church in Jarrow and Durham Cathedral. All the Northern Saints Trails use the same waymark shown on the left. The route also follows Bede’s Way from Jarrow to Monkwearmouth, The Weardale Way from New Lambton to Durham and Cuddy’s Corse from Chester-le-Street to Durham, so those way marks will also be helpful. The route is 61 kilometres or 38 miles. It is the most urban of the routes with two thirds of the route on minor roads or paved paths, but it is a route full of interest. I have divided the route into 5 sections of between 10 to 17 kms in length. Points of interest are described in red. The primary focus for the majority of pilgrims journeying to Durham Cathedral in the Middle Ages was the shrine of St Cuthbert, but the other most notable person, whose tomb is in the the Galilee Chapel in the cathedral, is the Venerable Bede. It is primarily because of him that this route is called The Way of Learning. He was indeed a man of great learning, who is probably best known for writing the first history of England. It was called An Ecclesiastical History of the English Speaking People. His other talents included the fact that was that he was an accomplished linguist, an astronomer and he also popularised measuring time from the birth of Christ. During his long life of extraordinary scholarship, he wrote 60 books. There are other connections with the theme of learning, apart from Bede, along the route. -

What's on Weekly

What's On Weekly South Tyneside Saturday 3rd October 2015 Reference and Local Studies Library Central Library, Prince Georg Square, South Shields NE33 2PE Tel: 0191 424 7864 Fax: 0191 455 8085 Email: [email protected] www.southtyneside.gov.uk/libraries Central Library: Children’s 0191 424 7885 Lending 0191 424 7888 Branch Libraries: Boldon Lane 0191 456 2852 Chuter Ede 0780 523 7650 Cleadon Park 0191 424 6194 East Boldon 0191 424 7853 Hebburn 0191 483 2088 Jarrow 0191 489 7786 Primrose 0191 489 8564 Whitburn 0191 529 3412 Saturday 3rd October 12noon-3.30pm. The Open University. Come and meet us in South Shields Central Library. Call in for an informal discussion to find out more about our courses, learning methods and other general study topics. No appointment necessary. www.open.ac.uk Call: 0300 303 5303. Older People’s Festival 2015 at South Tyneside Libraries Coffee Mornings Join the staff at our Library’s for our Older People’s Festival Coffee Mornings. Free. Knit and Natter Come along to one of our friendly, welcoming library knitting groups. Free. Mat Making Come along and join in with our friendly, informal clippy mat making session. Help a traditional craft come back to life, and enjoy a laugh and good company. Free. Monday 5th October Knit and Natter Central Library, South Shields, 10:00am-11:30am Knit and Natter Jarrow Library, 1:30pm-3:00pm Knit and Natter Boldon Lane Library, 2:00pm-3:30pm Online Books and Magazine Drop In Whitburn Library, 2:00pm-4:00pm Come along to find out about e-books and online magazines that you can borrow from the library and use at home on your computer or tablet. -

The British Museum Review 2019–20

Reaching out Review 2019/20 Contents 08 Director’s preface 10 Chairman’s foreword 14 Headlines Reaching out 26 New museums in Africa 28 Listening and learning 30 Fighting heritage crime 32 National moves 34 100 years of conservation and science National 38 National tours and loans 44 National partnerships 48 Archaeology and research in the UK International 56 International tours and loans 60 International partnerships Ready for X-ray 64 World archaeology and research 2020 marks 100 years since the BM launched one of the world’s London first dedicated museum science 72 Collection laboratories. Here the celebrated 76 Exhibitions Roman sculpture of the Discobolus 90 Learning (‘Discus-Thrower’) is shown in the X-ray imaging lab of the BM’s World 98 Support Conservation and Exhibitions Centre. 108 Appendices 6 Egyptian cat, c.600 BC Director’s preface The Gayer-Anderson cat, one of the most beloved objects in the BM, bears symbols of protection, healing and rebirth. (Height 14 cm) The month of March 2020 saw unprecedented Despite the profound change in our living and This situation does present an opportunity to think scenes at the British Museum as we responded working habits, and this strange enforced period more calmly, perhaps more profoundly, about our to the COVID 19 health crisis. BM colleagues of ‘exile’, I have been so pleased to see how our work and our achievements but also to think about were outstanding, helping us to close the audiences have continued to engage with the how to improve what we are doing once we have Museum in an orderly way and making sure collection and the BM digitally. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Contemporary and Competing Vistas: Public Perceptions of Wearmouth and Jarrow LAIDLER, SOPHIE,JANE How to cite: LAIDLER, SOPHIE,JANE (2011) Contemporary and Competing Vistas: Public Perceptions of Wearmouth and Jarrow, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3253/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Contemporary and Competing Vistas Public Perceptions of Wearmouth and Jarrow Volume 2. Appendices Sophie Jane Laidler Student Number: 000471901 “The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged.” Contemporary and Competing Vistas 2 Appendices Contents continued from Volume 1: Contents: Page(s): Appendix 1: Project Time Table 8.1. Project Flow Chart 3 8.2. Project Gantt Chart 4 Appendix 2 : Ethics 9.1. -

WEARMOUTH-JARROW WORLD HERITAGE STATUS.Doc

Item No. 14 CABINET MEETING – 6 OCTOBER 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SHEET – PART I Title of Report: WEARMOUTH-JARROW WORLD HERITAGE STATUS Author(s): Executive Director of City Services Purpose of Report: The purpose of this report is to advise Cabinet Members of the development of the Nomination of Wearmouth-Jarrow for World Heritage Status and to achieve the co- ordinated endorsement of the Nomination to support its submission to the Department of Culture Media and Sport. Description of Decision Cabinet Members are requested to: i) Note the activity relating to World Heritage. ii) Endorse the nomination of the Twin Anglo Saxon Monastery of Wearmouth- Jarrow, by the UK government, to the World Heritage List. iii) Give approval to the Executive Director of City Services, in consultation with the Member with Portfolio for Safer City, to exercise his rights under delegated powers for the Nomination File to go forward (as the UK’s Official Nomination) to the Secretary of State in December 2010 who subsequently submits to UNESCO in January 2011. Is the decision consistent with the Budget/Policy Framework? Yes If not, Council approval is required to change the Budget/Policy Framework Suggested reason(s) for Decision: The Nomination will be submitted to the Department for Culture Media and Sport as preparation for it becoming the UK’s official nomination to UNESCO in January 2011. In approving this nomination, the Secretary of State must be assured that the partners to the nomination stand foursquare behind it and endorse it. This report seeks that endorsement on behalf of Sunderland City Council.