Value-For-Money Audit: Indigenous Affairs in Ontario (2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Authors: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan with contributions from: Valerie McInnes Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Submitted to: Indigenous Services Canada Rolling River School Division Erickson Collegiate Institute Erickson Elementary School Rolling River First Nation Submitted by: Karen Rempel, Ph.D. Director, Centre for Aboriginal and Rural Education Studies (CARES) Faculty of Education Brandon University Written by: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan With contributions from: Valerie McInnes Table of Contents Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Manitoba Schools Executive Summary 1 Introduction 4 Process 5 Context of the Evaluators 6 Evaluation Framework 7 Program Evaluation Question 7 Program Evaluation Methodology 8 Data Collection and Assessment Inventory 8 Student Surveys 8 School Context Teacher Interviews 8 Data collection and analysis 9 Organization of this Report 9 Part 1: Introduction 10 Challenges of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education 10 Educational Achievement Gaps 11 Addressing Achievement Gaps 11 Context of Erickson, Manitoba Schools 12 Rolling River First Nation 12 Challenges for Erickson, Manitoba Schools in the Rolling River School Division 13 Cultural Proficiency: A Rolling River School Division Priority 13 Indigenization through the Application of Mino-Pimaatisiwin -

Cluster 2: a Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government

A Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government by Ted Longbottom C urrent t opiCs in F irst n ations , M étis , and i nuit s tudies Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence: First nations, Métis, and inuit relations with Government Setting the Stage: Economics and Politics by Ted Longbottom L earninG e xperienCe 2.1: s ettinG the s taGe : e ConoMiCs and p oLitiCs enduring understandings q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples share a traditional worldview of harmony and balance with nature, one another, and oneself. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples represent a diversity of cultures, each expressed in a unique way. q Understanding and respect for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples begin with knowledge of their pasts. q Current issues are really unresolved historical issues. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples want to be recognized for their contributions to Canadian society and to share in its successes. essential Questions Big Question How would you describe the relationship that existed among Indigenous nations and between Indigenous nations and the European newcomers in the era of the fur trade and the pre-Confederation treaties? Focus Questions 1. How did Indigenous nations interact? 2. How did First Nations’ understandings of treaties differ from that of the Europeans? 3. What were the principles and protocols that characterized trade between Indigenous nations and the traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company? 4. What role did Indigenous nations play in conflicts between Europeans on Turtle Island? Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence 27 Background Before the arrival of the Europeans, First Peoples were self-determining nations. -

(De Beers, Or the Proponent) Has Identified a Diamond

VICTOR DIAMOND PROJECT Comprehensive Study Report 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Overview and Background De Beers Canada Inc. (De Beers, or the Proponent) has identified a diamond resource, approximately 90 km west of the First Nation community of Attawapiskat, within the James Bay Lowlands of Ontario, (Figure 1-1). The resource consists of two kimberlite (diamond bearing ore) pipes, referred to as Victor Main and Victor Southwest. The proposed development is called the Victor Diamond Project. Appendix A is a corporate profile of De Beers, provided by the Proponent. Advanced exploration activities were carried out at the Victor site during 2000 and 2001, during which time approximately 10,000 tonnes of kimberlite were recovered from surface trenching and large diameter drilling, for on-site testing. An 80-person camp was established, along with a sample processing plant, and a winter airstrip to support the program. Desktop (2001), Prefeasibility (2002) and Feasibility (2003) engineering studies have been carried out, indicating to De Beers that the Victor Diamond Project (VDP) is technically feasible and economically viable. The resource is valued at 28.5 Mt, containing an estimated 6.5 million carats of diamonds. De Beers’ current mineral claims in the vicinity of the Victor site are shown on Figure 1-2. The Proponent’s project plan provides for the development of an open pit mine with on-site ore processing. Mining and processing will be carried out at an approximate ore throughput of 2.5 million tonnes/year (2.5 Mt/a), or about 7,000 tonnes/day. Associated project infrastructure linking the Victor site to Attawapiskat include the existing south winter road and a proposed 115 kV transmission line, and possibly a small barge landing area to be constructed in Attawapiskat for use during the project construction phase. -

Iroquois Falls Forest Independent Forest Audit 2005-2010 Audit Report

349 Mooney Avenue Thunder Bay, Ontario Canada P7B 5L5 Bus: 807-345- 5445 www.kbm.on.ca © Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2011 Iroquois Falls Forest – Independent Forest Audit 2005-2010 Audit Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... ii 2.0 Table of Recommendations and Best Practices ............................................................... 1 3.0 Introduction.................................................................................................................. ... 3 3.1 Audit Process ...................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Management Unit Description............................................................................................... 4 3.3 Current Issues ..................................................................................................................... 6 3.4 Summary of Consultation and Input to Audit .......................................................................... 6 4.0 Audit Findings .................................................................................................................. 6 4.1 Commitment.................................................................................................................... ... 6 4.2 Public Consultation and Aboriginal Involvement ...................................................................... 7 4.3 Forest Management Planning ............................................................................................... -

Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and Their Program Choices

Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and their Program Choices by Pamela Williamson A dissertation submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Higher Education Graduate Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto © Copyright by Pamela Williamson (2011) Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and their Post-Secondary Program Choices Doctor of Higher Education 2011 Pamela Williamson Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract The exploratory study focused on First Nation students and First Nation education counsellors within Ontario. Using an interpretative approach, the research sought to determine the relevance of the counsellors as a potentially influencing factor in the students‘ post-secondary program choices. The ability of First Nation education counsellors to be influential is a consequence of their role since they administer Post- Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP) funding. A report evaluating the program completed by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in 2005 found that many First Nation students would not have been able to achieve post-secondary educational levels without PSSSP support. Eight self-selected First Nation Education counsellors and twenty-nine First Nation post- secondary students participated in paper surveys, and five students and one counsellor agreed to complete a follow-up interview. The quantitative and qualitative results revealed differences in the perceptions of the two survey groups as to whether First Nation education counsellors influenced students‘ post-secondary program choices. -

TOXIC WATER: the KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It Was the Straw That Broke the Prover- Had Been Under a Boil-Water Alert on and Focus Bial Camel’S Back

TOXIC WATER: THE KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It was the straw that broke the prover- had been under a boil-water alert on and Focus bial camel’s back. A fax arrived from off for years. In fall 2005, Canadi- Health Canada (www.hc-sc.gc.ca) at the A week after the water tested positive ans were stunned to hear of the Kashechewan First Nations council for E. coli, Indian Affairs Minister appalling living office, revealing that E. coli had been Andy Scott arrived in Kashechewan. He conditions on the detected in the reserve’s drinking water. offered to provide the people with more Kashechewan First Enough was enough. A community bottled water but little else. Incensed by Nations Reserve in already plagued by poverty and unem- Scott’s apparent indifference, the Northern Ontario. ployment was now being poisoned by community redoubled their efforts, Initial reports documented the its own water supply. Something putting pressure on the provincial and presence of E. coli needed to be done, and some members federal governments to evacuate those in the reserve’s of the reserve had a plan. First they who were suffering from the effects of drinking water. closed down the schools. Next, they the contaminated water. The Ontario This was followed called a meeting of concerned members government pointed the finger at Ot- by news of poverty and despair, a of the community. Then they launched tawa because the federal government is reflection of a a media campaign that shifted the responsible for Canada’s First Nations. standard of living national spotlight onto the horrendous Ottawa pointed the finger back at the that many thought conditions in this remote, Northern province, saying that water safety and unimaginable in Ontario reserve. -

Waterfront Regeneration on Ontario’S Great Lakes

2017 State of the Trail Leading the Movement for Waterfront Regeneration on Ontario’s Great Lakes Waterfront Regeneration Trust: 416-943-8080 waterfronttrail.org Protect, Connect and Celebrate The Great Lakes form the largest group of freshwater During the 2016 consultations hosted by the lakes on earth, containing 21% of the world’s surface International Joint Commission on the Great Lakes, the freshwater. They are unique to Ontario and one of Trail was recognized as a success for its role as both Canada’s most precious resources. Our partnership is a catalyst for waterfront regeneration and the way the helping to share that resource with the world. public sees first-hand the progress and challenges facing the Great Lakes. Driven by a commitment to making our Great Lakes’ waterfronts healthy and vibrant places to live, work Over time, we will have a Trail that guides people across and visit, we are working together with municipalities, all of Ontario’s Great Lakes and gives residents and agencies, conservation authorities, senior visitors alike, an opportunity to reconnect with one of governments and our funders to create the most distinguishing features of Canada and the The Great Lakes Waterfront Trail. world. In 2017 we will celebrate Canada’s 150th Birthday by – David Crombie, Founder and Board Member, launching the first northern leg of the Trail between Waterfront Regeneration Trust Sault Ste. Marie and Sudbury along the Lake Huron North Channel, commencing work to close the gap between Espanola and Grand Bend, and expanding around Georgian Bay. Lake Superior Lac Superior Sault Garden River Ste. -

First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario's Northern Boreal

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations from 2009 2017 First Nation observations and perspectives on the changing climate in Ontario's Northern Boreal: forming bridges across the disappearing "Blue-Ice" (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom) Golden, Denise M. http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4202 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario’s Northern Boreal: Forming Bridges across the Disappearing “Blue-Ice” (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom). By Denise M. Golden Faculty of Natural Resources Management Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Forest Sciences 2017 © i ABSTRACT Golden, Denise M. 2017. First Nation Observations and Perspectives on the Changing Climate in Ontario’s Northern Boreal: Forming Bridges Across the Disappearing “Blue-Ice” (Kah-Oh-Shah-Whah-Skoh Siig Mii-Koom). Ph.D. in Forest Sciences Thesis. Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario. 217 pp. Keywords: adaptation, boreal forests, climate change, cultural continuity, forest carbon, forest conservation, forest utilization, Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous peoples, participatory action research, sub-Arctic Forests can have significant potential to mitigate climate change. Conversely, climatic changes have significant potential to alter forest environments. Forest management options may well mitigate climate change. However, management decisions have direct and long-term consequences that will affect forest-based communities. The northern boreal forest in Ontario, Canada, in the sub-Arctic above the 51st parallel, is the territorial homeland of the Cree, Ojibwe, and Ojicree Nations. -

Engineering & Mining Journal

Know-How | Performance | Reliability With MineView® and SmartFlow® Becker Mining Systems offers two comprehensive and scalable data management solutions for your Digital Mine. MineView® is a powerful state-of-the-art 3D SCADA system, that analyses incoming data from various mine equipment and visualises it in a 3D mine model. SmartFlow® takes Tagging & Tracking to a new level: collected asset data is centrally processed and smart software analytics allow for process optimization and improved safety. MINEVIEW BECKER MINING SYSTEMS AG We have been at the forefront of technology in Energy Distribution, Automation, Communication, Transportation and Roof Support since 1964. Together with our customers we create and deliver highest quality solutions and services to make operations run more profi tably, reliably and safely. For more information go to www.becker-mining.com/digitalmine Becker Mining is a trademark of Becker Mining Systems AG. © 2018 Becker Mining Systems AG or one of its affi liates. DECEMBER 2018 • VOL 219 • NUMBER 12 FEATURES China’s Miners Promote New Era of Openness and Cooperation Major reforms within the mining sector and the government will foster green mines at home and greater investment abroad ....................................42 Defeating the Deleterious Whether at the head of a circuit or scavenging tailings, today’s flotation innovations address challenges presented by declining grades, rising costs and aging plants ..................................................................................52 Staying on Top of -

20-24 October 14'20 Meeting

THE CORPORATION OF THE MUNICIPALITY OF HURON SHORES October 14, 2020 (20-24) - Regular The regular meeting of the Council of the Corporation of the Municipality of Huron Shores was held on Wednesday, October 14, 2020, and called to order by Mayor Georges Bilodeau at 7:44 p.m. PRESENT (Council Chambers): Mayor Georges Bilodeau, and Councillors Debora Kirby and Jock Pirrie PRESENT (electronically): Councillors Jane Armstrong, Gord Campbell, Nancy Jones-Scissons, Blair MacKinnon (lost connection from 7:17 - 7:20 p.m., and 8:38 - 8:55 p.m.), and Dale Wedgwood REGRETS: Councillor Darlene Walsh STAFF (Council Chambers): Clerk/Administrator Deborah Tonelli STAFF (electronically): Deputy Clerk Natashia Roberts, and Treasurer John Stenger (left meeting when Council went into closed session) DELEGATION (electronically): GALLERY (electronically): Joanne Falk (left shortly after Council returned to open session); Dan Gray (left when Council went into closed session); Peter Tonazzo (left at 8:11 p.m.); Jim Falconer (left when Council went into into closed session); Cornelia Poeschl (left at approximately 8:20 p.m.); Nancy Richards (left when Council went into closed session); David Ratz (left when Council went into closed session), Dave Smith (left when Council went into closed session) AGENDA REVIEW No changes made. DECLARATION OF PECUNIARY INTEREST Councillor Wedgwood declared a pecuniary interest respecting Item 5, pertaining to the Hughes Supply account. Councillor Kirby declared a pecuniary interest respecting Item 5, pertaining to the Tulloch Engineering account and Item 8b-1 (declared at the time the item came up for discussion on the agenda). Councillor Armstrong declared a pecuniary interest respecting Items 5, pertaining to the Armstrong Enterprise account, and Item 8d-2. -

How to Apply

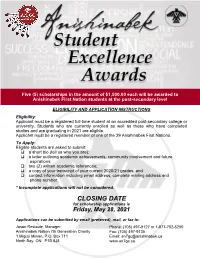

Five (5) scholarships in the amount of $1,500.00 each will be awarded to Anishinabek First Nation students at the post-secondary level ELIGIBILITY AND APPLICATION INSTRUCTIONS Eligibility: Applicant must be a registered full-time student at an accredited post-secondary college or university. Students who are currently enrolled as well as those who have completed studies and are graduating in 2021 are eligible. Applicant must be a registered member of one of the 39 Anishinabek First Nations. To Apply: Eligible students are asked to submit: a short bio (tell us who you are); a letter outlining academic achievements, community involvement and future aspirations; two (2) written academic references; a copy of your transcript of your current 2020/21 grades; and contact information including email address, complete mailing address and phone number. * Incomplete applications will not be considered. CLOSING DATE for scholarship applications is Friday, May 28, 2021 Applications can be submitted by email (preferred), mail, or fax to: Jason Restoule, Manager Phone: (705) 497-9127 or 1-877-702-5200 Anishinabek Nation 7th Generation Charity Fax: (705) 497-9135 1 Migizii Miikan, P.O. Box 711 Email: [email protected] North Bay, ON P1B 8J8 www.an7gc.ca Post-secondary students registered with the following Anishinabek First Nation communities are eligible to apply Aamjiwnaang First Nation Moose Deer Point Alderville First Nation Munsee-Delaware Nation Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Namaygoosisagagun First Nation Aundeck Omni Kaning Nipissing First Nation -

Formal Customary Care a Practice Guide to Principles, Processes and Best Practices

Formal Customary Care A Practice Guide to Principles, Processes and Best Practices In accordance with the Ontario Permanency Funding Policy Guidelines (2006) and the Child and Family Services Act Formal Customary Care* A Practice Guide to Principles, Processes and Best Practices *In accordance with the Ontario Permanency Funding Policy Guidelines (2006) and the Child and Family Services Act 2 Table of Contents Formal Customary Care Practice Guide Project Team ................................................................ 6 Disclaimers ................................................................................................................................... 6 Artwork ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. 7 Preamble ............................................................................................................................. 9 Success Indicator .......................................................................................................................... 9 Scope of the Guide ....................................................................................................................... 9 Clarification of Terms Used in this Practice Guide ................................................................... 10 Acronyms Used in this Practice Guide .....................................................................................