Gendering Migration Determinants: a Phenomenological Analysis of Professional Immigrant Women from India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The House of Dust

The House of Dust Conrad Aiken The House of Dust Table of Contents The House of Dust.....................................................................................................................................................1 Conrad Aiken.................................................................................................................................................1 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................1 PART I...........................................................................................................................................................1 PART II........................................................................................................................................................10 PART III......................................................................................................................................................23 PART IV......................................................................................................................................................48 i The House of Dust Conrad Aiken This page copyright © 2001 Blackmask Online. http://www.blackmask.com • NOTE • PART I. • PART II. • PART III • PART IV. THE HOUSE OF DUST A Symphony To Jessie NOTE . Parts of this poem have been printed in "The North American Review, Others, Poetry, Youth, Coterie, The Yale Review". I am indebted to Lafcadio Hearn for the episode -

PUSHING to the FRONT Volume II This E-Book by ORISON SWETT MARDEN Copyright 1911

Please Share PUSHING TO THE FRONT Click Here For This E-Book BY ORISON SWETT MARDEN Reading Tips Pushing to the Front BY ORISON SWETT MARDEN VOLUME II "The world makes way for the determined man.' PUBLISHED BY The Success Company's Branch Offices Digital Version 1.00 by www.arfalpha.com Created November 2003 PETERSBURG, TOLEDO DANVILLE N.Y. OKLAHOMA SAN JOSE CITY Please Share PUSHING TO THE FRONT Volume II This E-Book BY ORISON SWETT MARDEN Copyright 1911 COPYRIGHT, 1911 BY ORISON SWETT MARSDEN Please Share PUSHING TO THE FRONT Volume II This E-Book BY ORISON SWETT MARDEN Copyright 1911 CONTENTS VOLUME II Chapter PAGE XXXIII. PUBLICSPEAKING.............................................................. 411 XXXIV. THE TRIUMPHS OF THE COMMON VIRTUES......................... 424 XXXV. GETTING AROUSED............................................................ 433 XXXVI. THE MAN WITH AN IDEA..................................................... 439 XXXVII. DARE................................................................................ 452 XXXVIII. THE WILL AND THE WAY..................................................... 471 XXXIX. ONE UNWAVERING AIM..................................................... 485 XL. WORK AND WAIT.............................................................. 500 XLI. THE MIGHT of LITTLE THINGS............................................. 513 XLII. THE SALARY YOU DO NOT FIND IN YOUR PAY ENVELOPE....... 525 XLIII. EXPECT GREAT THINGS of YOURSELF................................... 540 XLIV. THE NEXT TIME YOU THINK -

The Fortunes & Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders &C

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders &c., by Daniel Defoe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders &c. Author: Daniel Defoe Release Date: March 19, 2008 [EBook #370] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOLL FLANDERS *** The Fortunes & Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders &c. Who was Born in Newgate, and during a Life of continu'd Variety for Threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother), Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv'd Honest, and dies a Penitent. Written from her own Memorandums … by Daniel Defoe 1 THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE The world is so taken up of late with novels and romances, that it will be hard for a private history to be taken for genuine, where the names and other circumstances of the person are concealed, and on this account we must be content to leave the reader to pass his own opinion upon the ensuing sheet, and take it just as he pleases. The author is here supposed to be writing her own history, and in the very beginning of her account she gives the reasons why she thinks fit to conceal her true name, after which there is no occasion to say any more about that. -

JANUS a Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillment O F ^ 0 1Q the R

JANUS A Written Creative Work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of ^ 0 1 q the requirements for m e w tte D q ,re e Master o f Fine Arts In Creative Writing by A i Ebashi San Francisco, California M ay 2019 Copyright by A i Ebashi 2019 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read JANUS by Ai Ebashi, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master o f Fine Arts in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. M ichelle Carter, M.F.A. Professor o f Creative Writing fry - Andrew Joron, B.A. Assistant Professor o f Creative Writing JANUS A i Ebashi San Francisco, California 2019 JANUS is a full-length play which portrays the moment of the psychic disintegration of the Roman God Janus and inner battles that ensue. It explores the themes o f gender, identity, duality, power structure and transgenderism. Through the lenses o f the divided Gods, He Janus and She Janus, who are trapped in an apocalyptic world, I used the yin and yang concept, symbol and dynamics to portray the two polarized forces that are forever opposing or conflicting but are also ultimately complementary. My approach to these themes is philosoph al but I also included physical movement, farcical element and outrageous happenings to create comedic effects. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation o f the content o f this written creative work. -

Stories by a Sioux Teacher Evelyn Alexandria Good Striker

Autobiography: Stories by a Sioux Teacher Evelyn Alexandria Good Striker B.Ed., University of Lethbridge, 1986 A One-Credit Project Submitted to the Faculty of Education of The University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA December, 1998 I ABSTRACT Human science research is a fOTTn of writing. Creating a phemonenological text is the object of the research proces-s- (Van Manen, 1990). In the case of this- project my writing. and research serves as pedagogy. Anecdotal narrative as story form is an effective way of dealing with certain kinds of knowledge. Anecdotes can -teach us. The use of story or of anecdotal material in phenomenological writing is not merely a literary embellishmenL The stories themselves are -examples -of practical theorizing. Anecdotal narratives {stories) are important for pedagogy in that they function as experiential case material on which pedagogic reflection is possible; H. Rosen (1986), points out the significance- and power of anecdotal llarrative: (1) to compel: a s-tory recruits- our willing. attention; (2) to lead us to reflect: a story tends to invite us to a reflective search for significance; (3) to involve us personally: one tends to search actively for the storyteller's . , meanmg VIa one sown; (4) to transform: we may be touched, shaken, moved by story; it teaches us; (5}tomeasureone!s interpretive sense: one's responsetoa story is a measure of one's deepened ability to make interpreti ve sense (Rosen, 1986). Famous- works- shared by the likes- of Van Manen and Rosen (and many others} have encouraged me to communicate my stories; to validate my life; to heal. -

Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol

Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 17, No. 97, January, 1876 Various The Project Gutenberg eBook, Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 17, No. 97, January, 1876, by Various, Edited by John Foster Kirk This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 17, No. 97, January, 1876 Author: Various Release Date: August 4, 2004 [eBook #13116] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LIPPINCOTT'S MAGAZINE OF POPULAR LITERATURE AND SCIENCE, VOL. 17, NO. 97, JANUARY, 1876*** E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Sandra Brown, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: The Table of Contents and the list of illustrations were added by the transcriber. Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 13116-h.htm or 13116-h.zip: (http://www.gutenberg.net/1/3/1/1/13116/13116-h/13116-h.htm) or (http://www.gutenberg.net/1/3/1/1/13116/13116-h.zip) LIPPINCOTT'S MAGAZINE OF POPULAR LITERATURE AND SCIENCE January, 1876. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. Volume XVII, No. 97 TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS THE CENTURY: ITS FRUITS AND ITS FESTIVAL. -

Pastors' Conference

missions group who have permeated our whole church with This testimony could not be complete without stating perhaps mission concern. They have succeeded in overcoming the idea that the most major contribution of all. Our women have had a large missions is a woman’s project. Filled with the spirit of compassion, role in making our church a praying fellowship. We have more they have led our church to see missions not as their thing, but prayer meetings than any other kind. Intercessory prayer is a as God's thing, and therefore everyone’s thing. Because of our major ministry of our church. WMU works in tandem with David Roddy whose commitment to These are reflections from a pastor’s grateful heart for WMU. religious education includes a commitment to missions education, It was in a Royal Ambassador chapter led by Mrs. Myers of the our people have an unusual awareness of the needs of the First Baptist Church in Olney, Texas that as a ten-year-old boy I sin-blighted world. For God’s people to be aware means to be learned that God’s people are here on business for our King. How active. The Cooperative Program, special missions offerings, world I thank the Lord Woman’s Missionary Union is still leading us to hunger, local and distant missions projects, are the activities born do the King’s business. of mission awareness. physical frame and it leaves in wreckage God’s beautiful creation. PASTORS' CONFERENCE That was why the Lord God used blood to teach Israel the For release after 7 :35 p.m., Sunday, June 10, penalty and judgment of sin and the necessity of atonement. -

Nothing to Lose but Your Head Talks Given from 13/2/76 To

Nothing to Lose But Your Head Talks given from 13/2/76 to 12/3/76 Darshan Diary 22 Chapters Year published: 1977 Nothing to Lose But Your Head Chapter #1 Chapter title: None 13 February 1976 pm in Chuang Tzu Auditorium Archive code: 7602135 ShortTitle: TOLOSE01 Audio: No Video: No [A visitor asked what the agreement of sannyas meant.] That you are no more. It is a total surrender. No agreement -- because in an agreement there are two parties. You simply surrender. Much courage is needed... It is not an agreement because it is not a legal thing. It is just a love affair... you fall in love. It is not an agreement because it is not a marriage. So if you feel love for me you take the jump and of course it needs courage, the greatest courage. All other courages are nothing compared to it, because before you were moving on familiar ground. Even if something new was there, it was not absolutely new. You knew it somehow; it had a context in your past, with your mind, with your intellect. You simply move in deep trust. Much happens through it -- and there is no other way of happening -- because once you put yourself aside, all barriers drop. Suddenly you are open, vulnerable. That is the meaning of courage -- to remain vulnerable. Whatsoever happens, one remains open. Storms may come, but still one never closes the doors. Once you close the door, it is closed against the enemy. It is also dosed against the friend. A closed door makes no difference between the enemy and the friend. -

Playing Destiny Elizabeth Jo Birmingham Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1994 Playing destiny Elizabeth Jo Birmingham Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Birmingham, Elizabeth Jo, "Playing destiny" (1994). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16228. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , Playing destiny by Elizabeth J. Bilmingham A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fultillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Creative Wliting) Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames. Iowa 1994 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1. 1 CHAPTER 2. 15 CHAPTER 3. 28 CHAPTER 4. 41 CHAPTER 5. 58 CHAPTER 6. 79 CHAPTER 7. 97 CHAPTER 8. 105 1 CHAPTER 1. Linear Kelt walked to campus everyday. To clear his head. He was beginning to feel his home life was, well, less than satisfactory. The old man was impossible. What was the boy? Uncommunicative. How could he know what the boy was? Rohan Bree never said, and anymore information could be neither cajoled nor coerced from him. He had simply become too strong for that Kelt hoped that the boy wouldn't realize he could defy them. -

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders

The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders Daniel Defoe The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders Table of Contents The Fortunes & Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders...........................................................................1 i The Fortunes & Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders &c. Who was Born in Newgate, and during a Life of continu'd Variety for Threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother), Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv'd Honest, and dies a Penitent. Written from her own Memorandums . by Daniel Defoe THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE The world is so taken up of late with novels and romances, that it will be hard for a private history to be taken for genuine, where the names and other circumstances of the person are concealed, and on this account we must be content to leave the reader to pass his own opinion upon the ensuing sheet, and take it just as he pleases. The author is here supposed to be writing her own history, and in the very beginning of her account she gives the reasons why she thinks fit to conceal her true name, after which there is no occasion to say any more about that. It is true that the original of this story is put into new words, and the style of the famous lady we here speak of is a little altered; particularly she is made to tell her own tale in modester words that she told it at first, the copy which came first to hand having been written in language more like one still in Newgate than one grown penitent and humble, as she afterwards pretends to be. -

The-Success-Principles-2-Chapters.Pdf

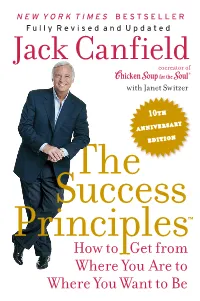

over all gloss/ 2 foil/ emboss 6 × 9 SPINE: 1 FLAPS: 0 Get ready to transform yourself for success 10th NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER with #1 New York Times bestselling author anniversary edition Fully Revised and Updated JACK CANFIELD! Canf “The results you’ll achieve will be extraordinary!” —ANTHONY ROBBINS, Jack author of Money: Master the Game and Awaken the Giant Within Jack Canfield ince its publication a decade ago, Jack Canfield’s practical and inspiring guide has become a cocreator of classic that has helped hundreds of thousands of people achieve success. This fully revised i eld hicken oup for the oul Sand updated edition of The Success Principles™ features one hundred pages of additional material, including a new section that offers a comprehensive guide to “Success in the Digital Age.” In this special 10th Anniversary Edition of his 500,000-copy bestseller, Canfield—the with Janet Switzer cocreator of the phenomenal bestselling Chicken Soup for the Soul® series—turns to the The Success Principles The Success principles he’s studied, taught, and lived for more than forty years in this practical and inspiring Get to How guide that will help any aspiring person get from where they are to where they want to be. The Success Principles™ will teach you how to increase your confidence, tackle daily chal- 10th lenges, live with passion and purpose, and realize all your ambitions. Not merely a collection of good ideas, this book spells out the 67 timeless principles and practices used by the world’s anniversary most successful men and women. -

Program Diva Universal Noiembrie 2014

NOIEMBRIE 2014 PROGRAM TV DIVA UNIVERSAL Pentru mai multe informaţii contactaţi: Alina Caraclischi [email protected] Produs de Tel: +44 20 7702 4436 www.globallistings.info NOIEMBRIE 2014 PAGE 2 sâmbătă Orson jură să o ajute pe Bree să-și duminică revină. Susan află cine e tatăl copilului 1 noiembrie 2014 lui Julie. Gemenii vor să se întoarcă 2 noiembrie 2014 acasă, dar Lynette nu e încântată. 06.00 Hercule Poirot: Hercule Poirot: 17.00 În mintea criminalului: Aur roșu – 06.00 Numai tată să nu fii !: Happy Elefanţii nu uită niciodată – Drama SERIES Drama, USA 2010, Thanksgiving – DRA, distribuţie: Series 2013 distribuţie: Simon Baker, Robin Lauren Graham, Peter Krause, Erika (Agatha Christie's Poirot: Elephants Tunney, Tim Kang Christensen Can Remember) Sezonul 13, Episodul (The Mentalist: Red Gold) Sezonul 3, (Parenthood: Happy Thanksgiving) 1 Episodul 15 Sezonul 2, Episodul 10 Poirot investighează moartea unui Agentul Hightower își unește forțele cu Camille şi Amber devin mai apropiate profesor. Ariadne Oliver se ocupă de o Patrick când Lisbon e rănită în timpul în timp ce pregătesc cina de Ziua tragedie petrecută pe o stâncă, în urmă anchetei asupra uciderii unui căutător Recunoştinţei. Adam se simte sfâşiat cu 13 ani. de aur. între carieră şi familie. 08.00 Hercule Poirot: Hercule Poirot: 18.00 În mintea criminalului: Regina roșie 07.00 FILM Sister Act 2: De la capăt – Societatea secretă – Drama Series – SERIES Drama, USA 2010, Comedy 1993, regia: Bill Duke, 2013 distribuţie: Simon Baker, Robin distribuţie: Whoopi Goldberg, Kathy (Agatha Christie's Poirot: The Big Four) Tunney, Tim Kang Najimy, James Coburn Sezonul 13, Episodul 2 (The Mentalist: Red Queen) Sezonul 3, (Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit) Se apropie Al Doilea Război Mondial.