Crossing Class Boundaries: Race, Siblings and Socioeconomic Heterogeneity. JCPR Working Paper. INSTITUTION Joint Center for Poverty Research, IL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Pattillo

Curriculum Vitae Mary Pattillo Northwestern University Home: 1810 Chicago Avenue 1036 E. 47th Street, #3E Evanston, IL 60208 Chicago, IL 60653 Tel. 847.491.3409; Fax 847.491.9907 [email protected] RESEARCH AND TEACHING AREAS Race and Ethnicity, Urban Sociology, Ethnographic Methods, Housing, Education, Criminal Justice EDUCATION 1997 Ph. D. in Sociology University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1994 M. A. in Sociology University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1991 B. A. cum laude in Urban Studies-Sociology Columbia University, New York, NY EMPLOYMENT 2020 - Chair, African American Studies Department 2010 - Harold Washington Professor, Departments of Sociology and African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2004 - Faculty Associate, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University 2006 - 2009 Chair, Department of Sociology 2001 - 2006 Associate to Full Professor, Departments of Sociology and African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2004-2007 Arthur Andersen Research and Teaching Professor, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2001 - 2002 Chair, African American Studies Department 1998 - 2001 Assistant to Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Department of African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 1998 - 2004 Faculty Fellow, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 1997 - 1998 Postdoctoral Fellow and Research Associate, Poverty Research and Training Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI -

A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2008 A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa T. Alexander, A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago, 17 J. Affordable Hous. & Cmty. Dev. L. 155 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/773 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFROM THE READING ROOM A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Waitingfor Gautreaux:A Story of Segregation,Housing, and the Black Ghetto By Alexander Polikoff I Northwestern University Press (2006) 422 pages Black on the Block: 2 The Politics of Race and Class in the City By Mary Pattillo University of Chicago Press (2007) 388 pages As the Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE VI)3 pro- gram enters its fifteenth year of implementation, two recent books pro- vide the historical context often missing from recent policy debates about HOPE VI's efficacy. Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto, by long-time legal crusader Alexander Polikoff, and Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, by award-winning sociologist Mary Pattillo, both convey the rich sociolegal history of public housing reform in Chicago. -

−1− Carrillo, Héctor

INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY (Sociology 110) - Fall 2012 Tu/Th 11am - 12:20pm, Leverone Hall - Coon Auditorium Professor: Professor Mary Pattillo Office hours: Wednesdays 2-6pm, 5-111 Crowe Hall Phone: 847-491-3409 (Sociology), 847-491-2036 (AFAM) E-mail: [email protected] TAs: TBA COURSE DESCRIPTION: Sociology is the study of the individual in a range of social contexts – from dyads (parent-child, romantic partners, boss-employee, assailant-victim) to large and anonymous, but somehow coherent, groups (e.g., Germans, Asian-Americans, bisexuals, lawyers), to institutions that surround and envelop us (religion, capitalism, sexism). This course aims to awaken students’ sociological imagination by going beneath our common sense assumptions to ask: How do social relationships, contexts, institutions and organizations work and how do we actively or passively participate? What are the major trends in employment, crime, political party affiliation, and racial inequality? How does sociology help to understand concepts like power, passion, and popularity? At root, all of these things are “social constructions,” but as the early sociologist W.I. Thomas teaches us “If men [and women] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” This course uses theory, research, and real-world examples to explore all three parts of this postulate: our definitions, the situations, and their consequences. COURSE OBJECTIVES: At the end of the course, students should be able to: • Recognize unacknowledged social processes that underlie everyday phenomena • Recognize, define, and utilize sociological vocabulary (e.g., stratification, correlation, reflexivity) • Define “social structure” and identify structural causes of social patterns • Apply your sociological imagination to generate questions about current and historical events EVALUATION: Grades will be based on a midterm (30%), research proposal (10%), paper (30%), and final (30%). -

"Give Me Something That Relates to My Life" : Exploring African American Adolescent Male Identities Through Young Adul

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 "Give me something that relates to my life" : exploring African American adolescent male identities through young adult literature Angelle Leblanc Hebert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Hebert, Angelle Leblanc, ""Give me something that relates to my life" : exploring African American adolescent male identities through young adult literature" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3588. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3588 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “GIVE ME SOMETHING THAT RELATES TO MY LIFE”: EXPLORING AFRICAN AMERICAN ADOLESCENT MALE IDENTITIES THROUGH YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Educational Theory, Policy, and Practice by Angelle L. Hebert B.A., Nicholls State University, 1995 M.Ed., Nicholls State University, 2005 August 2013 For Richie, Caroline, Maria, and Abbie ii Acknowledgments I am so very grateful to the individuals in my life who have made this journey possible for me. Whether through their scholarly expertise, their continual support, or their insistence on seeing me complete what I began—I am most thankful for the help of these people. -

Am2021-Program.Pdf

ASA is pleased to acknowledge the supporting partners of the 116th Virtual Annual Meeting 116th Virtual Annual Meeting Emancipatory Sociology: Rising to the Du Boisian Challenge 2021 Program Committee Aldon D. Morris, President, Northwestern University Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, Vice President, University of Southern California Nancy López, Secretary-Treasurer, University of New Mexico Joyce M. Bell, University of Chicago Hae Yeon Choo, University of Toronto Nicole Gonzalez Van Cleve, Brown University Jeff Goodwin, New York University Tod G. Hamilton, Princeton University Mignon R. Moore, Barnard College Pamela E. Oliver, University of Wisconsin-Madison Brittany C. Slatton, Texas Southern University Earl Wright, Rhodes College Land Acknowledgement and Recognition Before we can talk about sociology, power, inequality, we, the American Sociological Association (ASA), acknowledge that academic institutions, indeed the nation-state itself, was founded upon and continues to enact exclusions and erasures of Indigenous Peoples. This acknowledgement demonstrates a commitment to beginning the process of working to dismantle ongoing legacies of settler colonialism, and to recognize the hundreds of Indigenous Nations who continue to resist, live, and uphold their sacred relations across their lands. We also pay our respect to Indigenous elders past, present, and future and to those who have stewarded this land throughout the generations TABLE OF CONTENTS d Welcome from the ASA President..............................................................................................................................................................................1 -

A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-2008 A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa T. Alexander, A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago, 17 J. Affordable Hous. & Cmty. Dev. L. 155 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/773 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFROM THE READING ROOM A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Waitingfor Gautreaux:A Story of Segregation,Housing, and the Black Ghetto By Alexander Polikoff I Northwestern University Press (2006) 422 pages Black on the Block: 2 The Politics of Race and Class in the City By Mary Pattillo University of Chicago Press (2007) 388 pages As the Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE VI)3 pro- gram enters its fifteenth year of implementation, two recent books pro- vide the historical context often missing from recent policy debates about HOPE VI's efficacy. Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto, by long-time legal crusader Alexander Polikoff, and Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, by award-winning sociologist Mary Pattillo, both convey the rich sociolegal history of public housing reform in Chicago. -

Neighborhoods Black-White Mobility

NEIGHBORHOODS AND THE BLACK-WHITE MOBILITY GAP BY PATRICK SHARKEY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Patrick Sharkey is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at New York University and is a Faculty Affiliate at NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. His research focuses on the persistence of racial inequality in American neighborhoods in the post-civil rights era and the consequences of life in disadvantaged environments as experienced over generations of African-American families. The author gives special thanks to Scott Winship at the Economic Mobility Project who provided thoughtful feedback, edits, ideas, and suggestions throughout this project. Christopher Jencks also provided insightful comments and suggestions, many of which were implemented in the final analysis. Additional thanks go to Erin Currier, Harry Holzer, Ianna Kachoris, Marvin Kosters, Sara McLanahan and Robert Rector for their helpful comments on the research, and to Dalton Conley, Robert Sampson, Florencia Torche, William Julius Wilson, and Christopher Winship for feedback on previous research that is closely related to the work presented here. Lastly, the author also thanks Donna Nordquist at the Institute for Social Research at Michigan for her assistance with the PSID geocode data. Editorial assistance was provided by Ellen Wert, and design expertise by Carole Goodman of Do Good Design. All Economic Mobility Project materials are reviewed by members of the Principals’ Group and guided with input of the project’s Advisory Board (see back cover). The views expressed -

Punishment, Deterrence and Social Control: the Paradox of Punishment in Minority Communities

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2000 Punishment, Deterrence and Social Control: The Paradox of Punishment in Minority Communities Jeffrey Fagan Columbia Law School, [email protected] Tracey L. Meares [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey Fagan & Tracey L. Meares, Punishment, Deterrence and Social Control: The Paradox of Punishment in Minority Communities, OHIO STATE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW, VOL. 6, P. 173, 2008; COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL PUBLIC LAW & LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 00-10 (2000). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/1213 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Columbia Law School Public Law & Legal Theory Working Paper Group Paper Number 00-10 PUNISHMENT, DETERRENCE AND SOCIAL CONTROL: THE PARADOX OF PUNISHMENT IN MINORITY COMMUNITIES (version of Nov. 24, 2008) BY: PROFESSOR JEFFREY FAGAN COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL AND PROFESSOR TRACEY L. MEARES YALE LAW SCHOOL Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=223148 Punishment, Deterrence and Social Control: The Paradox of Punishment in Minority Communities† Jeffrey Fagan* and Tracey L. Meares** Since the early 1970s, the number of individuals in jails and state and federal prisons has grown exponentially. Today, nearly two million people are currently incarcerated in state and federal prisons and local jails. -

May 1 July 2020 Reuben A. Buford May Department of Sociology

July 2020 Reuben A. Buford May Department of Sociology University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 702 S. Wright St. 3084 Lincoln Hall Urbana, IL 61801 EDUCATION Ph.D. 1996, Sociology, University of Chicago M.A. 1991, Sociology, DePaul University B.A. 1987, Criminal Justice, Aurora University RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Race and Ethnicity, Urban Sociology, Sociology of Sport POSITIONS 2020-present Florian Znaniecki Professorial Scholar and Professor of Sociology, University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign 2018-2019 Associate Department Head, Department of Sociology, Texas A & M University 2017- Presidential Professor for Teaching Excellence, Texas A & M University 2015-2018 Glasscock University Professor in Undergraduate Teaching Excellence, Texas A & M University http://today.tamu.edu/2015/09/02/four-faculty-honored-with- professorships-for-undergraduate-teaching/ 2015 Interim Associate Department Head, Department of Sociology, Texas A & M University 2009-Present Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology, Texas A & M University 2011 Visiting Lectureship, Department of Sociology, Princeton University (Declined) May 1 2010 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Visiting Professor, School of the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2009 Sheila Biddle Ford Foundation Fellow, W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Harvard University 2008-present Faculty Affiliate, Africana Studies Program, Texas A & M University 2008-2009 Assistant Director, The Race and Ethnic Studies Institute, Texas A & M University 2005-2008 Associate Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology, Texas A & M University 2002-2005 Associate Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia 1996-2002 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia 1995 Lecturer, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, Illinois. -

The Middle-Class African American Home: Its Objects and Their Meanings Carol Lynnette Hall Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 The middle-class African American home: its objects and their meanings Carol Lynnette Hall Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Home Economics Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Carol Lynnette, "The middle-class African American home: its objects and their meanings " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 783. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/783 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The middle-class African American home: Its objects and their meanings by Carol Lynnette Hall A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Textiles and Clothing Program of Study Committee Mary Lynn Damhorst, Major Professor Mary Littrell Ann Marie Fiore Christine Cook Chalandra Bryant Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Carol Lynnette Hall, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3136316 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Moelis Institute

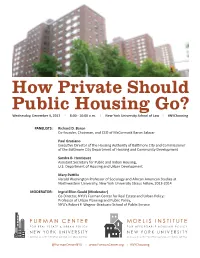

Wednesday, December 4, 2013 I 8:00 - 10:00 a.m. I New York University School of Law I #NYChousing PANELISTS: Richard D. Baron Co-founder, Chairman, and CEO of McCormack Baron Salazar Paul Graziano Executive Director of the Housing Authority of Baltimore City and Commissioner of the Baltimore City Department of Housing and Community Development Sandra B. Henriquez Assistant Secretary for Public and Indian Housing, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Mary Pattillo Harold Washington Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Northwestern University; New York University Straus Fellow, 2013-2014 MODERATOR: Ingrid Ellen Gould (Moderator) Co-Director, NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy; Professor of Urban Planning and Public Policy, NYU’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service FURMAN CENTER MOELIS INSTITUTE FOR REAL ESTATE & URBAN POLICY FOR AFFORDABLE HOUSING POLICY NEW YORK UNIVERSITY NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW • WAGNER SCHOOL OF PUBLIC SERVICE SCHOOL OF LAW • WAGNER SCHOOL OF PUBLIC SERVICE @FurmanCenterNYU I www.FurmanCenter.org I #NYChousing ABOUT THE PANELISTS RICHARD D. BARON Co-founder, Chairman, and CEO of McCormack Baron Salazar Richard D. Baron is co-founder, chairman, and chief executive officer of McCormack Baron Salazar (MBS), which redevelops neighborhoods in inner-city areas across the country. In the past thirty years, MBS has developed 157 projects with costs of $2.7 billion. It has developed more than 17,000 housing units and one million square feet of retail/ commercial space. MBS has closed 55 phases of HOPE VI developments in 15 cities involving 7,739 units and $1.4 billion in total development costs. -

April 1999 Number 4

VOLUME 27 APRIL 1999 NUMBER 4 Annual Meeting Special Event 1999 Annual Meeting Town Meeting with Kenneth Black Chicago Fourth in a series of articles in anticipation of the Prewitt on Census 2000 1999 ASA Annual Meeting in Chicago Bring a brown bag lunch to this by Mary Pattillo-Mccoy year’s Town Meeting on “Census and Northwestern University Consensus: Controversies in the 2000 Census” featuring Dr. Kenneth Prewitt, If only the winds had blown the Director of the U.S. Bureau of the great scholar and activist W.E.B. DuBois Census. Dr. Prewitt will open the westward, rather than east and south... session with a brief status report on the For with the noted exception of DuBois, well-being of the Census only nine nearly every classic contribution to the months out. A panel of sociologists sociological understanding of African will ask questions of Dr. Prewitt about American communities was influenced how to achieve a sound and scientifi- by Chicago as a “laboratory” in the true cally-accurate Census given the sense of the word—as a site for research, broader political climate that might training and theory building. While it is affect implementing the best Census plausible that my perspective is slanted plan possible. The full audience will by my own Chicago-based training and also be engaged in raising issues and Kenneth Prewitt empirical focus, “the list” overcomes probing questions to Dr. Prewitt. Every any such charge of subjectivity: E. “Where is this Black Chicago,” you attendee—as researcher and concerned and participate in an open and candid Franklin Frazier, Oliver Cromwell Cox, ask? Most of the famed streets of citizen—has a stake in a high-quality, discussion of where things stand.