Neighborhoods Black-White Mobility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black and Blue: Police-Community Relations in Portland's Albina

LEANNE C. SERBULO & KAREN J. GIBSON Black and Blue Police-Community Relations in Portland’s Albina District, 1964–1985 It appears that there is sufficient evidence to believe that the Portland Police Department indulges in stop and frisk practices in Albina. They seem to feel that they have the right to stop and frisk someone because his skin is black and he is in the black part of town. — Attorney commenting in City Club of Portland’s Report on Law Enforcement, 1981 DURING THE 1960s, institutionalized discrimination, unemployment, and police brutality fueled inter-racial tensions in cities across America, including Portland, Oregon. Riots became more frequent, often resulting in death and destruction. Pres. Lyndon Johnson’s National Advisory Com- mission on Civil Disorders issued in early 198 what became known as the “Kerner Report,” which declared that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”2 Later that year, the City Club of Portland published a document titled Report on Problems of Racial Justice in Portland, its own version of the national study. The report documented evidence of racial discrimination in numerous institutions, including the police bureau. The section “Police Policies, Attitudes, and Practices” began with the following statement: The Mayor and the Chief of Police have indicated that in their opinions the Kerner Report is not applicable to Portland. Satisfactory police-citizen relations are not likely to be achieved as a reality in Portland in the absence of a fundamental change in the philosophy of the officials who formulate policy for the police bureau. -

Black Seminoles Vs. Red Seminoles

Black Seminoles vs. Red Seminoles Indian tribes across the country are reaping windfall profits these days, usually from gambling operations. But some, like the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, are getting rich from belated government payouts for lands taken hundreds of years ago. What makes the Seminoles unique is that this tribe, unlike any other, has existed for nearly three centuries as a mixture of Indians and blacks, runaway slaves who joined the Indians as warriors in Florida. Together, they fought government troops in some of the bloodiest wars in U.S. history. In the late 1830s, they lost their land, and were forced to a new Indian home in present-day Oklahoma. Over the years, some tribe members have intermarried, blurring the color lines even further. Now the government is paying the tribe $56 million for those lost Florida lands, and the money is threatening to divide a nation. Seminole Chief Jerry Haney says the black members of the tribe are no longer welcome. After 300 years together, the chief says the tribe wants them to either prove they're Indian, or get out. Harsh words from the Seminole chief for the 2,000 black members of this mixed Indian tribe. In response, the black members say they're just as much a Seminole as Haney is. www.jupiter.fl.us/history On any given Sunday, go with Loretta Guess to the Indian Baptist church in Seminole County, Okla., and you'll find red and black Seminoles praying together, singing hymns in Seminole, sharing meals, and catching up on tribal news. -

Felix Elwert

July 2021 FELIX ELWERT University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Sociology and Center for Demography and Ecology 4426 Sewell Social Sciences Building 1180 Observatory Drive Madison, WI 53706 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS University of Wisconsin–Madison 2017- Professor, Department of Sociology Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics (affiliated) Department of Population Health Sciences (affiliated) 2013–2017 Associate Professor (Affiliated), Department of Population Health Sciences 2012–2017 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology 2007–2012 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Germany 2015–2016 Acting Director, Research Unit Social Inequality and Social Policy 2014–2015 Karl W. Deutsch Visiting Professor Harvard Medical School 2006–2007 Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Health Care Policy EDUCATION 2007 Ph.D., Sociology, Harvard University 2006 A.M., Statistics, Harvard University 1999 M.A., Sociology, New School for Social Research 1997 Vordiplom, Sociology, Free University of Berlin Felix Elwert / May 2020 AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS 2018 Leo Goodman Award, Methodology Section, American Sociological Association 2018 Elected member, Sociological Research Association 2018 Vilas Midcareer Faculty Award, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2017- H. I. Romnes Faculty Fellowship, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2016-2018 Fellow, WZB Berlin Social Science Center, Berlin, Germany 2013 Causality in Statistics Education Award, American Statistical Association 2013 Vilas Associate Award, University of Wisconsin–Madison 2012 Jane Addams Award (Best Paper), Community and Urban Sociology Section, American Sociological Association 2010 Gunther Beyer Award (Best Paper by a Young Scholar), European Association for Population Studies 2009, 2010, 2017 University Housing Honored Instructor Award, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2009 & 2010 Best Poster Awards, Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America 2005–2006 Eliot Fellowship, Harvard University 2004 Aage B. -

Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J

EDTRUST.ORG Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J. Oliver Schak Andrew Howard Nichols, Ph.D., is the senior director of higher education research and data analytics and J. Oliver Schak is the senior policy and research associate for higher education at The Education Trust Understanding the economic and social benefits of more college-educated residents, over 40 states during the past decade have set goals to increase their state’s share of adults with college credentials and degrees. In many of these states, achieving these “degree attainment” goals will be directly related to their state’s ability to increase the shares of Black and Latino adults in those states that have college credentials and degrees, particularly as population growth among communities of color continues to outpace the White population and older White workers retire and leave the workforce.1 From 2000 to 2016, for example, the number of Latino adults increased 72 percent and the number of Black adults increased 25 percent, while the number of White adults remained essentially flat. Nationally, there are significant differences in degree attainment among Black, Latino, and White adults, but degree attainment for these groups and the attainment gaps between them vary across states. In this brief, we explore the national trends and state-by-state differences in degree attainment for Black adults, ages 25 to 64 in 41 states.2 We examine degree attainment for Latino adults in a companion brief. National Degree Attainment Trends FIGURE 1 DEGREE ATTAINMENT FOR BLACK AND WHITE ADULTS, 2016 Compared with 47.1 percent of White adults, just 100% 30.8 percent of Black adults have earned some form 7.8% 13.4% 14.0% 30.8% of college degree (i.e., an associate degree or more). -

Moving to Inequality: Neighborhood Effects and Experiments Meet Social Structure1

Moving to Inequality: Neighborhood Effects and Experiments Meet Social Structure1 Robert J. Sampson Harvard University The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) housing experiment has proven to be an important intervention not just in the lives of the poor, but in social science theories of neighborhood effects. Competing causal claims have been the subject of considerable disagreement, culmi- nating in the debate between Clampet-Lundquist and Massey and Ludwig et al. in this issue. This article assesses the debate by clar- ifying analytically distinct questions posed by neighborhood-level theories, reconceptualizing selection bias as a fundamental social process worthy of study in its own right rather than a statistical nuisance, and reconsidering the scientific method of experimenta- tion, and hence causality, in the social world of the city. The author also analyzes MTO and independent survey data from Chicago to examine trajectories of residential attainment. Although MTO pro- vides crucial leverage for estimating neighborhood effects on indi- viduals, as proponents rightly claim, this study demonstrates the implications imposed by a stratified urban structure and how MTO simultaneously provides a new window on the social reproduction of concentrated inequality. Contemporary wisdom traces the idea of neighborhood effects to William Julius Wilson’s justly lauded book, The Truly Disadvantaged (1987). Since its publication, a veritable explosion of work has emerged, much of it attempting to test the hypothesis that living in a neighborhood of con- 1 I am indebted to Corina Graif for superb research assistance and to Patrick Sharkey for his collaborative work on neighborhood selection. They both provided incisive comments as well, as did Nicholas Christakis, Steve Raudenbush, Bruce Western, P.-O. -

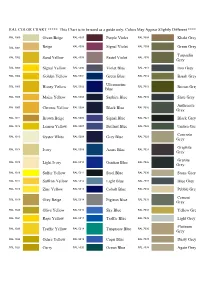

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Crossing Class Boundaries: Race, Siblings and Socioeconomic Heterogeneity. JCPR Working Paper. INSTITUTION Joint Center for Poverty Research, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 460 236 UD 034 696 AUTHOR Heflin, Colleen M.; Pattillo, Mary TITLE Crossing Class Boundaries: Race, Siblings and Socioeconomic Heterogeneity. JCPR Working Paper. INSTITUTION Joint Center for Poverty Research, IL. SPONS AGENCY Ford Foundation, New York, NY.; Northwestern Univ., Evanston, IL. Inst. for Policy Research. REPORT NO JCPR-WP-252 PUB DATE 2002-01-07 NOTE 23p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: Lpattillo.pdf. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blacks; Middle Class; Poverty; *Racial Differences; *Siblings; Social Mobility; *Socioeconomic Status; Whites ABSTRACT This study used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (comprised of three subsamples taken in 1979) to characterize the siblings of middle class and poor Blacks and Whites, testing for racial differences in the probability of having a sibling on the other side of the socioeconomic divide. In support of theories in the urban poverty literature about the social isolation of poor blacks, results found that African Americans were less likely than Whites to have siblings who crossed social lines in w'ays that were beneficial. Low-income African Americans were less likely to have a middle class sibling than were low-income Whites, and middle class African Americans were more likely than middle class Whites to have a low-income sibling. Therefore, low-income African Americans were less likely to have a sibling to turn to for help but more likely to have a sibling to turn to them for assistance if they were middle class. The study results suggest that racial differences in the composition of kin networks may indicate another dimension of racial stratification. -

Color Chart See Next Page for Trim-Gard Color Program

COLOR CHART SEE NEXT PAGE FOR TRIM-GARD COLOR PROGRAM 040–SUPER WHITE 068–POLAR WHITE 070–BLIZZARD PEARL 071–ARCTIC FROST OUG–PLATINUM 1C8–LUNAR MIST 1D4–TITANIUM 1F7–CLASSIC SILVER 700–ALABASTER 017–SWITCHBLADE OUX–INGOT SILVER 1D6–SILVER SKY 1F8–METEOR METAL 1F9–SLATE METAL 1G3–MAGNET GRAY 797–MOD STEEL 0J7–MAGNETIC METAL 8V1–WINTER GRAY 1EO–FLINT MICA 202–BLACK 209–BLACK SAND ORR–RUBY RED 3L5–RADIENT RED 3PO–ABSOLUTE RED 089–CRYSTAL RED 3R3–BARCELONA RED 3Q7–CASSIS PEARL 102–CHAMPAGNE 402–DESERT SAND 4T8–SANDY BEACH 4T3–PYRITE MICA 4U2–GOLDEN UMBER 4U3–SUNSET BRNZ 6T3–BLACK FOREST 6T6–EVERGLADE 6T8–TIMBERLAND 8S6–NAUTICAL BLUE 8T0–BLAZING BLUE 8Q5–COSMIC BLUE 8T5–BLUE RIBBON 8T7–BLUE STREAK 8R3–PACIFIC BLUE ACTUAL COLORS MAY VARY SLIGHTLY COLOR PROGRAM BULLET END TIPS ANGLE END TIPS WHEEL WELL DOOR EDGE COLOR 14XXXBT BTXXX 15XXXAT 75XXXAT 20XXXAT 3XXX NEXXX 000 - CLEAR X X 017 - SWITCHBLADE SILVER X X X X 040 - SUPER WHITE X X X X X X X 068 - POLAR WHITE X X X X X 070 - BLIZZARD PEARL X X X X X X 071 - ARCTIC FROST X X X X 089 - CRYSTAL RED TINTCOAT X X X X 0J7 - MAGNETIC METALLIC X X X X 0RR - RUBY RED METALLIC X X X X X 0UG - WHITE PLATINUM PEARL X X X X 0UX - INGOT SILVER METALLIC X X X X 102 - CHAMPAGNE SILVER X X X X 1C8 - LUNAR MIST X X X 1D4 - TITANIUM METALLIC X X X X X 1D6 - SILVER SKY X X X X X 1E0 - FLINT MICA X X X 1E7 - SILVER STREAK X X X 1F7 - CLASSIC SILVER X X X X X X X 1F8 - METEOR METALLIC X X X 1F9 - SLATE METALLIC X X X 1G3 - MAGNETIC GRAY X X X X X X X 202 - BLACK X X X X X X X 209 - BLACK SAND PEARL X X X X 3L5 -

The Bigger Picture Black Womenomics

The Bigger Picture | March 9, 2021 BLACK WOMENOMICS Investing in the Underinvested Daan Struyven Gizelle George-Joseph Daniel Milo [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. Goldman Sachs The Bigger Picture Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Confronting the Wealth Gap 6 Earnings Gap 8 Education Gap 12 Capital Access Gap 15 Personal Finance Gap 19 Housing Gap 21 Health Gap 22 Actions to Invest in the Underinvested 27 Good for Growth 30 Fairer and Richer Society 31 Disclosure Appendix 32 The Bigger Picture is a publication series from Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research devoted to longer-term economic and policy issues, which complements our more market-focused analysis. For other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix. BLACK9 March WOMENOMICS 2021 2 2 Goldman Sachs The Bigger Picture ExecutiveExecutive Summary Summary 1. Black women face a 90% wealth gap. The economic and business case for diversity will only grow as US demographics and the labor force are set to become increasingly racially and ethnically diverse over the coming decades. Yet, due to complex historical factors and ongoing discrimination, Black Americans and especially Black women remain heavily disadvantaged across a broad range of economic measures, including wealth, earnings, and health. The median Black household owns nearly 90% less wealth than the median white household and the gap is even slightly larger for single Black women relative to single white men. The structural factors that have created and reinforced these economic disparities that Black women face are multifaceted and interrelated, and inevitably we neglect many important issues. -

The Crime and Society Issue

FALL 2020 THE CRIME AND SOCIETY ISSUE Can Academics Such as Paul Butler and Patrick Sharkey Point Us to Better Communities? Michael O’Hear’s Symposium on Violent Crime and Recidivism Bringing Baseless Charges— Darryl Brown’s Counterintuitive Proposal for Progress ALSO INSIDE David Papke on Law and Literature A Blog Recipe Remembering Professor Kossow Princeton’s Professor Georgetown’s Professor 1 MARQUETTE LAWYER FALL 2020 Patrick Sharkey Paul Butler FROM THE DEAN Bringing the National Academy to Milwaukee—and Sending It Back Out On occasion, we have characterized the work of Renowned experts such as Professors Butler and Sharkey Marquette University Law School as bringing the world and the others whom we bring “here” do not claim to have to Milwaukee. We have not meant this as an altogether charted an altogether-clear (let alone easy) path to a better unique claim. For more than a century, local newspapers future for our communities, but we believe that their ideas have brought the daily world here, as have, for decades, and suggestions can advance the discussion in Milwaukee broadcast services and, most recently, the internet. And and elsewhere about finding that better future. many Milwaukee-based businesses, nonprofits, and So we continue to work at bringing the world here, organizations are world-class and world-engaged. even as we pursue other missions. To reverse the phrasing Yet Marquette Law School does some things in this and thereby to state another truth, we bring Wisconsin regard especially well. For example, in 2019 (pre-COVID to the world in issues of this magazine and elsewhere, being the point), about half of our first-year students had not least in the persons of those Marquette lawyers been permanent residents of other states before coming who practice throughout the United States and in many to Milwaukee for law school. -

Mary Pattillo

Curriculum Vitae Mary Pattillo Northwestern University Home: 1810 Chicago Avenue 1036 E. 47th Street, #3E Evanston, IL 60208 Chicago, IL 60653 Tel. 847.491.3409; Fax 847.491.9907 [email protected] RESEARCH AND TEACHING AREAS Race and Ethnicity, Urban Sociology, Ethnographic Methods, Housing, Education, Criminal Justice EDUCATION 1997 Ph. D. in Sociology University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1994 M. A. in Sociology University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1991 B. A. cum laude in Urban Studies-Sociology Columbia University, New York, NY EMPLOYMENT 2020 - Chair, African American Studies Department 2010 - Harold Washington Professor, Departments of Sociology and African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2004 - Faculty Associate, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University 2006 - 2009 Chair, Department of Sociology 2001 - 2006 Associate to Full Professor, Departments of Sociology and African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2004-2007 Arthur Andersen Research and Teaching Professor, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 2001 - 2002 Chair, African American Studies Department 1998 - 2001 Assistant to Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Department of African American Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 1998 - 2004 Faculty Fellow, Institute for Policy Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 1997 - 1998 Postdoctoral Fellow and Research Associate, Poverty Research and Training Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI -

A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2008 A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lisa T. Alexander, A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago, 17 J. Affordable Hous. & Cmty. Dev. L. 155 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/773 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFROM THE READING ROOM A Sociolegal History of Public Housing Reform in Chicago Lisa T. Alexander Waitingfor Gautreaux:A Story of Segregation,Housing, and the Black Ghetto By Alexander Polikoff I Northwestern University Press (2006) 422 pages Black on the Block: 2 The Politics of Race and Class in the City By Mary Pattillo University of Chicago Press (2007) 388 pages As the Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE VI)3 pro- gram enters its fifteenth year of implementation, two recent books pro- vide the historical context often missing from recent policy debates about HOPE VI's efficacy. Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto, by long-time legal crusader Alexander Polikoff, and Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City, by award-winning sociologist Mary Pattillo, both convey the rich sociolegal history of public housing reform in Chicago.