The Bigger Picture Black Womenomics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black and Blue: Police-Community Relations in Portland's Albina

LEANNE C. SERBULO & KAREN J. GIBSON Black and Blue Police-Community Relations in Portland’s Albina District, 1964–1985 It appears that there is sufficient evidence to believe that the Portland Police Department indulges in stop and frisk practices in Albina. They seem to feel that they have the right to stop and frisk someone because his skin is black and he is in the black part of town. — Attorney commenting in City Club of Portland’s Report on Law Enforcement, 1981 DURING THE 1960s, institutionalized discrimination, unemployment, and police brutality fueled inter-racial tensions in cities across America, including Portland, Oregon. Riots became more frequent, often resulting in death and destruction. Pres. Lyndon Johnson’s National Advisory Com- mission on Civil Disorders issued in early 198 what became known as the “Kerner Report,” which declared that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”2 Later that year, the City Club of Portland published a document titled Report on Problems of Racial Justice in Portland, its own version of the national study. The report documented evidence of racial discrimination in numerous institutions, including the police bureau. The section “Police Policies, Attitudes, and Practices” began with the following statement: The Mayor and the Chief of Police have indicated that in their opinions the Kerner Report is not applicable to Portland. Satisfactory police-citizen relations are not likely to be achieved as a reality in Portland in the absence of a fundamental change in the philosophy of the officials who formulate policy for the police bureau. -

Black Seminoles Vs. Red Seminoles

Black Seminoles vs. Red Seminoles Indian tribes across the country are reaping windfall profits these days, usually from gambling operations. But some, like the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, are getting rich from belated government payouts for lands taken hundreds of years ago. What makes the Seminoles unique is that this tribe, unlike any other, has existed for nearly three centuries as a mixture of Indians and blacks, runaway slaves who joined the Indians as warriors in Florida. Together, they fought government troops in some of the bloodiest wars in U.S. history. In the late 1830s, they lost their land, and were forced to a new Indian home in present-day Oklahoma. Over the years, some tribe members have intermarried, blurring the color lines even further. Now the government is paying the tribe $56 million for those lost Florida lands, and the money is threatening to divide a nation. Seminole Chief Jerry Haney says the black members of the tribe are no longer welcome. After 300 years together, the chief says the tribe wants them to either prove they're Indian, or get out. Harsh words from the Seminole chief for the 2,000 black members of this mixed Indian tribe. In response, the black members say they're just as much a Seminole as Haney is. www.jupiter.fl.us/history On any given Sunday, go with Loretta Guess to the Indian Baptist church in Seminole County, Okla., and you'll find red and black Seminoles praying together, singing hymns in Seminole, sharing meals, and catching up on tribal news. -

Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J

EDTRUST.ORG Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends Authors: Andrew Howard Nichols and J. Oliver Schak Andrew Howard Nichols, Ph.D., is the senior director of higher education research and data analytics and J. Oliver Schak is the senior policy and research associate for higher education at The Education Trust Understanding the economic and social benefits of more college-educated residents, over 40 states during the past decade have set goals to increase their state’s share of adults with college credentials and degrees. In many of these states, achieving these “degree attainment” goals will be directly related to their state’s ability to increase the shares of Black and Latino adults in those states that have college credentials and degrees, particularly as population growth among communities of color continues to outpace the White population and older White workers retire and leave the workforce.1 From 2000 to 2016, for example, the number of Latino adults increased 72 percent and the number of Black adults increased 25 percent, while the number of White adults remained essentially flat. Nationally, there are significant differences in degree attainment among Black, Latino, and White adults, but degree attainment for these groups and the attainment gaps between them vary across states. In this brief, we explore the national trends and state-by-state differences in degree attainment for Black adults, ages 25 to 64 in 41 states.2 We examine degree attainment for Latino adults in a companion brief. National Degree Attainment Trends FIGURE 1 DEGREE ATTAINMENT FOR BLACK AND WHITE ADULTS, 2016 Compared with 47.1 percent of White adults, just 100% 30.8 percent of Black adults have earned some form 7.8% 13.4% 14.0% 30.8% of college degree (i.e., an associate degree or more). -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Color Chart See Next Page for Trim-Gard Color Program

COLOR CHART SEE NEXT PAGE FOR TRIM-GARD COLOR PROGRAM 040–SUPER WHITE 068–POLAR WHITE 070–BLIZZARD PEARL 071–ARCTIC FROST OUG–PLATINUM 1C8–LUNAR MIST 1D4–TITANIUM 1F7–CLASSIC SILVER 700–ALABASTER 017–SWITCHBLADE OUX–INGOT SILVER 1D6–SILVER SKY 1F8–METEOR METAL 1F9–SLATE METAL 1G3–MAGNET GRAY 797–MOD STEEL 0J7–MAGNETIC METAL 8V1–WINTER GRAY 1EO–FLINT MICA 202–BLACK 209–BLACK SAND ORR–RUBY RED 3L5–RADIENT RED 3PO–ABSOLUTE RED 089–CRYSTAL RED 3R3–BARCELONA RED 3Q7–CASSIS PEARL 102–CHAMPAGNE 402–DESERT SAND 4T8–SANDY BEACH 4T3–PYRITE MICA 4U2–GOLDEN UMBER 4U3–SUNSET BRNZ 6T3–BLACK FOREST 6T6–EVERGLADE 6T8–TIMBERLAND 8S6–NAUTICAL BLUE 8T0–BLAZING BLUE 8Q5–COSMIC BLUE 8T5–BLUE RIBBON 8T7–BLUE STREAK 8R3–PACIFIC BLUE ACTUAL COLORS MAY VARY SLIGHTLY COLOR PROGRAM BULLET END TIPS ANGLE END TIPS WHEEL WELL DOOR EDGE COLOR 14XXXBT BTXXX 15XXXAT 75XXXAT 20XXXAT 3XXX NEXXX 000 - CLEAR X X 017 - SWITCHBLADE SILVER X X X X 040 - SUPER WHITE X X X X X X X 068 - POLAR WHITE X X X X X 070 - BLIZZARD PEARL X X X X X X 071 - ARCTIC FROST X X X X 089 - CRYSTAL RED TINTCOAT X X X X 0J7 - MAGNETIC METALLIC X X X X 0RR - RUBY RED METALLIC X X X X X 0UG - WHITE PLATINUM PEARL X X X X 0UX - INGOT SILVER METALLIC X X X X 102 - CHAMPAGNE SILVER X X X X 1C8 - LUNAR MIST X X X 1D4 - TITANIUM METALLIC X X X X X 1D6 - SILVER SKY X X X X X 1E0 - FLINT MICA X X X 1E7 - SILVER STREAK X X X 1F7 - CLASSIC SILVER X X X X X X X 1F8 - METEOR METALLIC X X X 1F9 - SLATE METALLIC X X X 1G3 - MAGNETIC GRAY X X X X X X X 202 - BLACK X X X X X X X 209 - BLACK SAND PEARL X X X X 3L5 -

Race, Health, and COVID-19: the Views and Experiences of Black Americans

October 2020 Race, Health, and COVID-19: The Views and Experiences of Black Americans Key Findings from the KFF/Undefeated Survey on Race and Health Prepared by: Liz Hamel, Lunna Lopes, Cailey Muñana, Samantha Artiga, and Mollyann Brodie KFF Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 4 The Big Picture: Being Black in America Today ........................................................................................... 6 The Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic .......................................................................... 11 Views Of A Potential COVID-19 Vaccine .................................................................................................... 16 Trust And Experiences In The Health Care System ................................................................................... 22 Trust of Providers and Hospitals ............................................................................................................. 22 Perceptions of Unfair Treatment in Health Care ..................................................................................... 24 Experiences With and Access to Health Care Providers ........................................................................ 26 Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................. -

The Black-White Test Score Gap: an Introduction

CHRISTOPHER JENCKS MEREDITH PHILLIPS 1 The Black-White Test Score Gap: An Introduction FRICAN AMERICANS currently score lower than A European Americans on vocabulary, reading, and mathematics tests, as well as on tests that claim to measure scholastic apti- tude and intelligence.1 This gap appears before children enter kindergarten (figure 1-1), and it persists into adulthood. It has narrowed since 1970, but the typical American black still scores below 75 percent of American whites on most standardized tests.2 On some tests the typical American black scores below more than 85 percent of whites.3 1. We are indebted to Karl Alexander, William Dickens, Ronald Ferguson, James Flynn, Frank Furstenberg, Arthur Goldberger, Tom Kane, David Levine, Jens Ludwig, Richard Nisbett, Jane Mansbridge, Susan Mayer, Claude Steele, and Karolyn Tyson for helpful criticisms of earlier drafts. But we did not make all the changes they suggested, and they are in no way responsible for our conclusions. 2. These statistics also imply, of course, that a lot of blacks score above a lot of whites. If the black and white distributions are normal and have the same standard deviation, and if the black-white gap is one (black or white) standard deviation, then when we compare a randomly selected black to a randomly selected white, the black will score higher than the white about 24 percent of the time. If the black-white gap is 0.75 rather than 1.00 standard deviations, a randomly selected black will score higher than a randomly selected white about 30 percent of the time. -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

Liberal Party Colours

Conservatives have blue, Labour have red and Liberal Democrats have yellow – but it wasn’t always like that. Graham Lippiatt examines the history of: LIBERal PARTY ColoURS lections of sorts have been than the intrinsic usefulness This was the case in Liverpool and held in the United Kingdom of the message itself.5 Some of Cumbria and across many parts of Esince the days of the knights this has been driven by election south-east England. The Liberal of the shires and burgesses of the legislation such as the use of party colours in Greenwich (then a two- boroughs.1 These elections were logos on ballot papers6 but it has member parliamentary borough in taking place before universal literacy come about principally as society, Kent), which Gladstone represented (in England; Scotland always had communication technology and from 1868 to 1880, were blue. When much higher literacy rates), even politics have changed and the Gladstone fought Greenwich in among the limited electorates nature of political communication 1874 he fought in blue and his two before the Great Reform Acts and organisation has changed Conservative opponents used of 18322 and during the advances with them. The Conservative crimson, while his Radical running towards the mass democratic state Party tree, the Labour rose or the mate, in honour of his support for of the twentieth century. So it Liberal Democrat freebird will Irish home rule, adopted green.8 was important to ensure that rival be the ubiquitous symbols of each More recently, Liberal colours candidates were properly identified, organisation and candidates and were traditionally blue in Berwick particularly in the days before the literature will be adorned in the on Tweed until changed by Alan secret ballot and the printed ballot same blue, red or yellow colours. -

R Color Cheatsheet

R Color Palettes R color cheatsheet This is for all of you who don’t know anything Finding a good color scheme for presenting data about color theory, and don’t care but want can be challenging. This color cheatsheet will help! some nice colors on your map or figure….NOW! R uses hexadecimal to represent colors TIP: When it comes to selecting a color palette, Hexadecimal is a base-16 number system used to describe DO NOT try to handpick individual colors! You will color. Red, green, and blue are each represented by two characters (#rrggbb). Each character has 16 possible waste a lot of time and the result will probably not symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F: be all that great. R has some good packages for color palettes. Here are some of the options “00” can be interpreted as 0.0 and “FF” as 1.0 Packages: grDevices and i.e., red= #FF0000 , black=#000000, white = #FFFFFF grDevices colorRamps palettes Two additional characters (with the same scale) can be grDevices comes with the base cm.colors added to the end to describe transparency (#rrggbbaa) installation and colorRamps topo.colors terrain.colors R has 657 built in color names Example: must be installed. Each palette’s heat.colors To see a list of names: function has an argument for rainbow colors() peachpuff4 the number of colors and see P. 4 for These colors are displayed on P. 3. transparency (alpha): options R translates various color models to hex, e.g.: heat.colors(4, alpha=1) • RGB (red, green, blue): The default intensity scale in R > #FF0000FF" "#FF8000FF" "#FFFF00FF" "#FFFF80FF“ ranges from 0-1; but another commonly used scale is 0- 255. -

"Fifty Shades of Black": the Black Racial Identity Development Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 4-15-2018 "Fifty Shades of Black": The lB ack Racial Identity Development of Black Members of White Greek Letter Organizations in the South Danielle Ford Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Ford, Danielle, ""Fifty Shades of Black": The lB ack Racial Identity Development of Black Members of White Greek Letter Organizations in the South" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4697. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4697 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FIFTY SHADES OF BLACK”: THE BLACK RACIAL IDENTITY DEVELOPMENT OF BLACK MEMBERS OF WHITE GREEK LETTER ORGANIZATIONS IN THE SOUTH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Education by Danielle Ford B.S. Louisiana State University, 2012 May 2018 Don’t Quit When things go wrong as they sometimes will, When the road you're trudging seems all up hill, When the funds are low and the debts are high And you want to smile, but you have to sigh, When care is pressing you down a bit, Rest if you must, but don't you quit. -

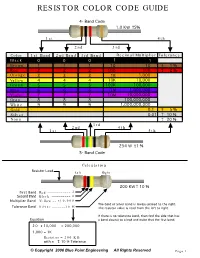

Resistor Color Code Guide

RESISTOR COLOR CODE GUIDE 4- Band Code 1.0 KW +- 5% 1st 4th 2nd 3rd Color 1st Band 2nd Band 3rd Band Decimal Multiplier Tolerance Black 0 0 0 1 1 Brown 1 1 1 10 10 +- 1 % Red 2 2 2 100 100 +- 2 % Orange 3 3 3 1K 1,000 Yellow 4 4 4 10K 10,000 Green 5 5 5 100K 100,000 Blue 6 6 6 1M 1,000,000 Violet 7 7 7 10M 10,000,000 Gray 8 8 8 100,000,000 White 9 9 9 1,000,000,000 Gold 0.1 +- 5 % Silver 0.01 +- 10 % None +- 20 % 3rd 2nd 4th 1st 5th 254 W +- 1 % 5- Band Code Calculation Resistor Lead Left Right 200 KW +- 10 % First Band Red 2 Second Band Black 0 Multiplier Band Yellow x10,000 The Gold or Silver band is always placed to the right. Tolerance Band Silver 10 % The resistor value is read from the left to right. If there is no tolerance band, then find the side that has Equation a band closest to a lead and make that the first band. 2 0 x 10,000 = 200,000 1,000 = 1K Resistor = 200 K with a + - 10 % Tolerance © Copyright 2006 Blue Point Engineering All Rights Reserved Page 1 Resistor Color Code 4 Band Quick Guide Resistance Notation Band 1 Band 2 Band 3 Tolerance .22 ohm R22 Red Red Silver S,G,R,B .27 ohm R27 Red Purple Silver S,G,R,B Color Value .33 ohm R33 Orange Orange Silver S,G,R,B Black 0 .39 ohm R39 Orange White Silver S,G,R,B Brown 1 .47 ohm R47 Yellow Purple Silver S,G,R,B Red 2 .56 ohm R56 Green Blue Silver S,G,R,B Orange 3 .68 ohm R68 Blue Gray Silver S,G,R,B Yellow 4 .82 ohm R82 Gray Red Silver S,G,R,B Green 5 1.0 ohm 1R0 Brown Black Gold S,G,R,B Blue 6 1.1 ohm 1R1 Brown Brown Gold S,G,R,B Violet 7 1.2 ohm 1R2 Brown Red Gold S,G,R,B