The India-China Conflict in the Himalaya Should Break Open IR Theory Written by Alexander Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh Kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online Journal of Political Sciences & Public Affairs Editorial 1962 Sino-Indian Conflict : Battle of Eastern Ladakh Agnivesh kumar* Department of Sociology, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India. E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL protests. Later they also constructed a road from Lanak La to Kongka Pass. In the north, they had built another road, west of the Aksai Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 in Eastern Ladakh was fought in the area Chin Highway, from the Northern border to Qizil Jilga, Sumdo, between Karakoram Pass in the North to Demchok in the South East. Samzungling and Kongka Pass. The area under territorial dispute at that time was only the Aksai Chin plateau in the north east corner of Ladakh through which the Chinese In the period between 1960 and October 1962, as tension increased had constructed Western Highway linking Xinjiang Province to Lhasa. on the border, the Chinese inducted fresh troops in occupied Ladakh. The Chinese aim of initially claiming territory right upto the line – Unconfirmed reports also spoke of the presence of some tanks in Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) – Track Junction and thereafter capturing it general area of Rudok. The Chinese during this period also improved in October 1962 War was to provide depth to the Western Highway. their road communications further and even the posts opposite DBO were connected by road. The Chinese also had ample animal In Galwan – Chang Chenmo Sector, the Chinese claim line was transport based on local yaks and mules for maintenance. The horses cleverly drawn to include passes and crest line so that they have were primarily for reconnaissance parties. -

India's Military Strategy Its Crafting and Implementation

BROCHURE ONLINE COURSE INDIA'S MILITARY STRATEGY ITS CRAFTING AND IMPLEMENTATION BROCHURE THE COUNCIL FOR STRATEGIC AND DEFENSE RESEARCH (CSDR) IS OFFERING A THREE WEEK COURSE ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. AIMED AT STUDENTS, ANALYSTS AND RESEARCHERS, THIS UNIQUE COURSE IS DESIGNED AND DELIVERED BY HIGHLY-REGARDED FORMER MEMBERS OF THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES, FORMER BUREAUCRATS, AND EMINENT ACADEMICS. THE AIM OF THIS COURSE IS TO HELP PARTICIPANTS CRITICALLY UNDERSTAND INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY INFORMED BY HISTORY, EXAMPLES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE. LED BY PEOPLE WHO HAVE ‘BEEN THERE AND DONE THAT’, THE COURSE DECONSTRUCTS AND CLARIFIES THE MECHANISMS WHICH GIVE EFFECT TO THE COUNTRY’S MILITARY STRATEGY. BY DEMYSTIFYING INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY AND WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE IT, THE COURSE CONNECTS THE CRAFTING OF THIS STRATEGY TO THE LOGIC BEHIND ITS CRAFTING. WHY THIS COURSE? Learn about - GENERAL AND SPECIFIC IDEAS THAT HAVE SHAPED INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY ACROSS DECADES. - INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS AND PROCESSES. - KEY DRIVERS AND COMPULSIONS BEHIND INDIA’S STRATEGIC THINKING. Identify - KEY ACTORS AND INSTITUTIONS INVOLVED IN DESIGNING MILITARY STRATEGY - THEIR ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES. - CAUSAL RELATIONSHIPS AMONG A MULTITUDE OF VARIABLES THAT IMPACT INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. Understand - THE REASONING APPLIED DURING MILITARY DECISION MAKING IN INDIA - WHERE THEORY MEETS PRACTICE. - FUNDAMENTALS OF MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND ESCALATION/DE- ESCALATION DYNAMICS. - ROLE OF DOMESTIC POLITICS IN AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. - THREAT PERCEPTION WITHIN THE DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT AND ITS MILITARY ARMS. Explain - INDIA’S MILITARY ORGANIZATION AND ITS CONSTITUENT PARTS. - INDIA’S MILITARY OPTIONS AND CONTINGENCIES FOR THE REGION AND BEYOND. - INDIA’S STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS AND OUTREACH. -

Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring

SANDIA REPORT SAND2007-5670 Unlimited Release Printed September 2007 Demilitarization of the Siachen Conflict Zone: Concepts for Implementation and Monitoring Brigadier (ret.) Asad Hakeem Pakistan Army Brigadier (ret.) Gurmeet Kanwal Indian Army with Michael Vannoni and Gaurav Rajen Sandia National Laboratories Prepared by Sandia National Laboratories Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185 and Livermore, California 94550 Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under Contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. Approved for public release; further dissemination unlimited. Issued by Sandia National Laboratories, operated for the United States Department of Energy by Sandia Corporation. NOTICE: This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors or subcontractors. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government, any agency thereof, or any of their contractors. Printed in the United States of America. -

History of Project Vartak

Brig JS Ishar Chief Engineer HISTORY OF PROJECT VARTAK The Beginning 1. During the second meeting of BRDB on 13 May 1960, late Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the then Prime Minister directed that the work on the construction of Road Bhalukpong- Tenga should commence on 01 Jun 1960. Accordingly, Project Tusker was raised on 07 May 1960. Thus Project Tusker was the first in Border Roads Organisation to commence road construction activity. 2. Project Tusker was also made responsible for the maintenance of road Missamari- Foothills-Chaku-Tenga, which had been constructed by PWD. Elephant Gate: Entry To Bomdila-Tawang Road 3. Work on the improvement of the Road Bhalukpong-Tenga-Bomdila was continued by 14 BRTF, which was raised in early 1962. The most difficult stretch on this high priority road was between Sessa and Bomdila. The task was completed in 6 months and the road was made trafficable by Oct 1962. Further improvements continued. Shri YB Chavan, the then Defence Minister formally opened the road in Apr 1963. 4. In 1962, a jeepable track Bomdila-Dirang-Sela-Tawang was also attempted. A Signals Task Force was raised for laying of telephone lines for Bomdila-Tawang, North Lakhimpur-Lekhabali-Along, Kimin-Ziro and Along-Daporijo sector. Initial Problems 5. During the initial induction of the Project, there were many teething problems. Maj Gen OM Mani, the first Chief Engineer (then Brigadier) of the Project later recalled:- “The Administrative Offices functioned under the cover of tarpaulins spread over bamboos. The office furniture comprised of a few packing cases and even these were in short supply. -

Realignment and Indian Air Power Doctrine

Realignment and Indian Airpower Doctrine Challenges in an Evolving Strategic Context Dr. Christina Goulter Prof. Harsh Pant Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs requests a courtesy line. ith a shift in the balance of power in the Far East, as well as multiple chal- Wlenges in the wider international security environment, several nations in the Indo-Pacific region have undergone significant changes in their defense pos- tures. This is particularly the case with India, which has gone from a regional, largely Pakistan-focused, perspective to one involving global influence and power projection. This has presented ramifications for all the Indian armed services, but especially the Indian Air Force (IAF). Over the last decade, the IAF has been trans- forming itself from a principally army-support instrument to a broad spectrum air force, and this prompted a radical revision of Indian aipower doctrine in 2012. It is akin to Western airpower thought, but much of the latest doctrine is indigenous and demonstrates some unique conceptual work, not least in the way maritime air- power is used to protect Indian territories in the Indian Ocean and safeguard sea lines of communication. Because of this, it is starting to have traction in Anglo- American defense circles.1 The current Indian emphases on strategic reach and con- ventional deterrence have been prompted by other events as well, not least the 1999 Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan, which demonstrated that India lacked a balanced defense apparatus. -

Evaluating India-China Tactical Military Standoff Through Strategic Lens

1 EVALUATING INDIA-CHINA TACTICAL MILITARY STANDOFF THROUGH STRATEGIC LENS * Dr. Ahmed Saeed Minhas, Dr. Farhat Konain Shujahi and Dr. Raja Qaiser Ahmed Abstract India and China are two big neighbours by all respects, may it be geography, military might, natural resources, leading international engagements, armed forces in terms of quality, aspirations for global dominance, vibrant economy, plausible market and above all nuclear weapons states. India since its inception has not been under normal strategic relations with China. The international border between India and China has yet to be formalized and thus still termed as Line of Actual Control (LAC). In May 2020, the two sides had a face-off in Ladakh area having potential of spiralling up to uncontrollable limits, if not immediately, in future for sure. India under its hardliner nationalist political leadership is looking for regional hegemony with due American political, military and diplomatic support. India by strengthening its military infrastructure at Ladakh in Western Indian Held Kashmir (IHK) is suspected to build a jump-off point to check China-Pakistan Economic Corridor moving through Pakistani Gilgit Baltistan (GB) area. The tactical level Indo-China stand-off in Ladakh has strategic implications for South Asian peace and stability. Keywords: Kashmir, Line of Actual Control (LAC), India-China Rivalry, China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and Strategic Stability. Introduction ndo-China bilateral relations have come to a standstill which over a period of time I had remained veiled with limited face valued engagements at different levels. Although, in the past India and China had summit level meetings having main agenda of addressing territorial disputes. -

BRIEF ABOUT SIACHEN CIV TREK for ADG PI 1. the Siachen Glacier Trek for the Year 2016 Will Be Conducted from 15 September To

BRIEF ABOUT SIACHEN CIV TREK FOR ADG PI 1. The Siachen Glacier Trek for the year 2016 will be conducted from 15 September to 15 October 2016 in the ruggedized terrain of Siachen. A total of 45 volunteers from different fields to include cadets from Rashtriya Indian Military College, Rashtriya Military School and National Cadet Corps, dependents of Army pers of all Comds, pers posted at IHQ of MoD (Army) and civilians will be shortlisted for the trek. 2. Indian Army has been conducting Annual High Altitude trek to Siachen Glacier since 2007 commencing from Siachen base camp to Kumar post and back in the month of Sep/Oct every year keeping in mind the prevailing weather conditions. The aim of the trek is to expose the participants to harsh realities and regime of nature and terrain faced by the Indian Army. This unique adventure activity is organized to motivate younger generation to join Indian Army. 3. The vacancies for civilians are allotted to Indian Mountaineering Foundation, being the nodal agency. Indian Mountaineering Foundation selects the names of participants and sends it to Army Adventure Wing. For media, the vacancies are given to Additional Directorate General of PubIic Information and for cadets of Rashtriya Indian Military College, Rashtriya Military School and National Cadet Corps, the vacancies are given to concerned directorates. The last dates for submission of application is 01 Aug 2016. 4. Enthusiastic volunteers may contact the under mentioned officer for further query / clarification, if any:- General Staff Officer-1 (Land & Coord) Military Adventure Wing Military Training Directorate Integrated Headquarters of Ministry of Defence (Army) DHQ PO New Delhi-110011, Phone No -23016548 (Civil) Email –[email protected] 5. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Are India and China Destined for War? Three Future Scenarios

19 ARE INDIA AND CHINA DESTINED FOR WAR? THREE FUTURE SCENARIOS Srini Sitaraman “Frontiers are indeed the razor’s edge on which hang suspended the modern issues of war or peace, of life or death to nations.” Lord Curzon Introduction The Greek historian Thucydides writing on the Peloponnesian War argued that when an established power encounters a rising power, the possibility of conflict between the established and rising power would become in- evitable.1 Graham T. Allison in his book, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, extended Thucydides’ primary argument by suggesting that the power dynamics between China and the United States is similarly poised, an established power—the United States—confronting an aggressive power in China may produce a military conflict between them.2 The Thucydides Trap argument has also been applied to the India- China conflict, in which India, a rising power, is confronted by China, the established power.3 But such comparisons are unsatisfactory because of the power asymmetry is against India. The overall military, economic, and political balance of power tilts towards China. Chinese strategists discount India as a serious security or economic threat. For China, India assumes substantial low priority military threat compared to the United States.4 More often India is described as a “barking dog” that must be ignored and its policy actions are described as having little political impact.5 In- dia has resisted the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), refused to the join the Beijing-led -

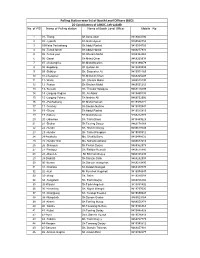

ERONET Pre Reqst Format.Xlsx

Polling Station wise list of Booth Level Officers (BLO) 26-Constituency of LAHDC, Leh-Ladakh No. of P/S Name of Polling station Name of Booth Level Officer Mobile . No 1 01- Thang Sh Sana Ullah 9419864100 2 02 -Tyakshi Sh Mohs Ayoub 9469552752 3 03Waha Pachathang Sh Abdul Rashid 9419534709 4 04 -Turtuk farool Sh Abdul Hamid 9469277933 5 05 -Turtuk youl Sh Ghulam Mohd 9469462863 6 06 -Garari Sh Mohd Omar 9469265938 7 07 -Chulungkha Sh Mohd Ibrahim 9419388079 8 08 -Bogdang Sh Qurban Ali 9419829393 9 09 -Skilkhor Sh. Shamsher Ali 9419971169 10 10-Changmar Sh Mohd Ali Khan 9469265209 11 11- Waris Sh. Ghulam Mohd 9469515130 12 12 -Fastan Sh Ghulam Mohd 9469531252 13 13- Sunudo Sh. Thoskor Spalgyas 9469176699 14 14 -Largyap Gogma Sh. Ali Akbar 9419440193 15 15 -Largyap Yokma Sh Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 16 16 –Pachathang Sh Mohd Hassan 9419386471 17 17 -Terchay Sh Sonam Nurboo 9419880947 18 18 –Skuru Sh Abdul Rashid 9419515915 19 19 -Rakuru Sh Mohd Mussa 9469212778 20 20 -Udmaroo Sh. Tashi Dawa 9419440625 21 21 -Shukur Sh Tsering Dorjey 9469178364 22 22 -Hundri Sh. Stanzin Dorjay 9469617039 23 23 -Hunder Sh Tashi Wangdus 9419550812 24 24-Awaksha Ms. Shakila Bano 9419448032 25 25 -Hunder Dok Ms. Naheda Akhatar 9469572613 26 26 -Skampuk Sh Tsetan Dorjey 9469362975 27 27 -Partapur Sh. Rehbar Hussain 9469571886 28 28 –Diskit-A Sh Rinchen Dorjey 9469165230 29 29-Diskit-B Sh Stanzin Galik 9469292903 30 30 -Burma Sh Stanzin Wangchok 9469213895 31 31 -Charasa Sh Deldan Namgail 9469387070 32 32 –Kuri Mr Punchok Angchok 9419974947 33 33- Murgi Sh. -

ORF Issue Brief 23 Rajeswari P & K Prasad

EARCH S F E O R U R N E D V A R T E I O S N B O ORF ISSUE BRIEF August 2010 ISSUE BRIEF # 23 Sino-Indian Border Infrastructure: Issues and Challenges* Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan & Kailash Prasad Introduction in the politico-strategic arena, as tension and suspicion continue to strain bilateral relations. These Asia has been at the centre of emerging global tensions do manifest themselves, from time to time, politics, for a variety of reasons. Some of the world's on the border and at various diplomatic fora. India's major military powers—India, China, Russia and the border tension with China is only a symptom of the US—are in Asia; six of the nine nuclear powers are in larger problem in the India-China equation. This is Asia; some of the fastest growing economies are in likely to continue until there is clarity on the Line of Asia. Among these, China is an important country Actual Control (LAC). Despite the talks since 1981, whose rise is inevitable but there is a need to the big push by successive Prime Ministers (Rajiv recognize that the rise of any one power does not lead Gandhi during his visit in 1988, Atal Bihari Vajpayee to a period of more insecurities and instability in the during his visit in 2003, Manmohan Singh in his talks region. Since India, China and Japan are the rising with Premier Wen Jiabao in 2005 and President Hu powers in Asia they have to find ways of working Jintao in 2006, Manmohan Singh's visit in January with each other and not against each other. -

Kibithoo Can Be Configured As an Entrepôt in Indo- China Border Trade

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Kibithoo Can Be Configured as an Entrepôt in Indo- China Border Trade JAJATI K PATTNAIK Jajati K. Pattnaik ([email protected]) is an Associate Professor, at the Department of Political Science, Indira Gandhi Government College, Tezu (Lohit District), Arunachal Pradesh Vol. 54, Issue No. 5, 02 Feb, 2019 Borders are the gateway to growth and development in the trajectory of contemporary economic diplomacy. They provide a new mode of interaction which entails de-territorialised economic cooperation and free trade architecture, thereby making the spatial domain of territory secondary in the global economic relations. Taking a cue from this, both India and China looked ahead to revive their old trade routes in order to restore cross-border ties traversing beyond their political boundaries. Borders are the gateway to growth and development in the trajectory of contemporary economic diplomacy. They provide a new mode of interaction which entails de-territorialised economic cooperation and free trade architecture, thereby making the spatial domain of territory secondary in the global economic relations. Taking a cue from this, both India and China looked ahead to revive their old trade routes in order to restore cross-border ties traversing beyond their political boundaries. The reopening of the Nathula trade route in 2016 was realised as a catalyst in generating trust and confidence between India and China. Subsequently, the success of Nathula propelled the academia, policymakers and the civil society to rethink the model in the perspective of Arunachal Pradesh as well. So, the question that automatically arises here is: Should we apply this cross-border model in building up any entrepôt in Arunachal Pradesh? The response is positive and corroborated by my field interactions at the ground level.