EVOLVING FEMALE SEXUALITY in INDIAN CINEMA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

1 Bombay Dreams and Bombay Nightmares

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Bombay dreams and Bombay nightmares: Spatiality and Bollywood gangster film's urban underworld aesthetic AUTHORS Stadtler, FCJ JOURNAL Journal of Postcolonial Writing DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 February 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/31264 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Bombay dreams and Bombay nightmares: Spatiality and Bollywood gangster film’s urban underworld aesthetics Florian Stadtler * Department of English and Film, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK E-mail: [email protected] The importance of the city in an articulation of Indian modernity has been central to the narratives of Indian popular cinema since the 1950s. Much of the focus has been centred on Bombay/Mumbai. Especially since the mid-1970s, in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s declaration of a State of Emergency, Hindi cinema has explored the structures of power that determine Bombay’s urban city space where the hero of the film encounters exponentially communal, domestic, gang, and state violence. These films put forward textured views of the cityscape and address overtly its potential for corruption and violence. In the process commercial Indian cinema challenges the city’s status as a shining example of progress and modernity. Focussing on post-millennial Indian popular film, especially Milan Luthria’s Once Upon a Time in Mumbaai (2010), this article explores Hindi cinema’s engagement with urban violence in an age of market liberalisation, accelerated economic growth and planned expansion. -

7 Most Memorable Oscar Moments Taapsee Pannu

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 17 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA MARCH 2017 TOTAL RECALL: 7 MOST ST GUE MemoraBle VIEW INter OScar MomeNTS SEE TAAP PANNU THE BEST NEW MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: PHILLAPVR UMOVIESRI, FIRSTBADR INATH KI DULHANIYA, BEAUTY AND THE BEAST, chIPS, LIFE PAGE 1 GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, Taapsee Pannu takes us behind the scenes of “Naam Shabana.” Dishy 007 Daniel Craig loves cooking Here’s the March edition of Movies First, your exclusive and hates guns! Join us in wishing the superstar a window to the world of cinema. Happy Birthday. After playing the character for 17 years, Hugh Jackman makes We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous his final bow as Wolverine in “Logan,” our Movie of the Month. month of movie watching. Bring on the dhol and join the baraat as Varun and Alia rekindle their sparkling chemistry in “Badrinath ki Dulhania.” Regards Anushka Sharma haunts a groom-to-be in “Phillauri” while Rajkummar Rao finds himself “Trapped“ inside a Mumbai apartment. Treat yourself to the poignant “Sense of an Ending” Gautam Dutta and edgy real-life thriller “Patriots Day” this month. CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope youa’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAY TRAILER SET REMINDER BOOK TICKETS SHARE PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS Join the action as Hugh Jackman reprises the role of Wolverine for one last time. -

Seeing Like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-Centric Bollywood Films

Seeing like a Feminist: Representations of Societal Realities in Women-centric Bollywood Films Sutapa Chaudhuri, University of Calcutta, India The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2014 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract One of the most notable contemporary trends in Indian cinema, the genre of women oriented films seen through a feminist lens, has gained both critical acclaim and sensitive audience reception for its experimentations with form and cinematic representations of societal realities, especially women’s realities in its subject matter. The proposed paper is based on readings of such women centric, gender sensitive Bollywood films like Tarpan, Matrubhoomi or The Dirty Picture that foreground the harsh realities of life faced by women in the contemporary patriarchal Indian society, a society still plagued by evils like female foeticide/infanticide, gender imbalance, dowry deaths, child marriage, bride buying, rape, prostitution, casteism or communalism, issues that are glossed over, negated, distorted or denied representation to preserve the entertaining, escapist nature of the melodramatic, indeed addictive, panacea that the high-on-star-quotient mainstream Bollywood films, the so-called ‘masala’ movies, offer to the lay Indian masses. It would also focus on new age cinemas like Paheli or English Vinglish, that, though apparently following the mainstream conventions nevertheless deal with the different complex choices that life throws up before women, choices that force the women to break out from the stereotypical representation of women and embrace new complex choices in life. The active agency attributed to women in these films humanize the ‘fantastic’ filmi representations of women as either exemplarily good or baser than the basest—the eternal feminine, or the power hungry sex siren and present the psychosocial complexities that in reality inform the lives of real and/or reel women. -

Freemuse-The-State-Of-Artistic-Freedom

THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2018 FREEMUSE THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2018 1 Freemuse is an independent international organisation advocating for and defending freedom of artistic expression. We believe that at the heart of violations of artistic freedom is the effort to silence opposing or less preferred views and values by those in power – politically, religiously or societally – mostly due to fear of their transformative effect. With this assumption, we can address root causes rather than just symptoms – if we hold violators accountable. Our approach to artistic freedom is human rights-based as it provides an international legal framework and lays out the principles of accountability, equality and non-discrimination, and participation. ©2018 Freemuse. All rights reserved. ISSN 2596-5190 Design: www.NickPurser.com Infographics: sinnwerkstatt Medienagentur Author: Srirak Plipat Research team: Dwayne Mamo, David Herrera, Ayodele Ganiu, Jasmina Lazovic, Paige Collings, Kaja Ciosek and Joann Caloz Michaëlis Freemuse would like to thank Sara Wyatt, Deji Olatoye, Andra Matei, Sarah Hossain, Shaheen Buneri, Irina Aksenova and Magnus Ag for their review, research assistance and feedback. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of February 2018. Nevertheless, Freemuse cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. This report is kindly supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Fritt Ord Norway. THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2018 FREEMUSE THE STATE OF ARTISTIC FREEDOM 2018 3 I draw and I paint whenever “ I can. -

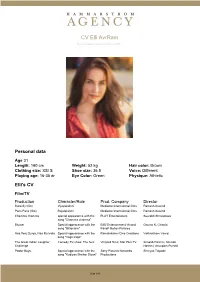

Elli Avrram CV

CV Elli AvrRam Senast uppdaterad 2021-05-18 09:14 Personal data Age 31 Length: 160 cm Weight: 52 kg Hair color: Brown Clothing size: XS/ S Shoe size: 36.5 Voice: Different Playing age: 16-35 år Eye Color: Green Physique: Athletic Elli's CV Film/TV Production Character/Role Prod. Company Director Butterfly (film) Vijaylakshmi Mediente International films Ramesh Aravind Paris Paris (film) Rajalakshmi Mediente International films Ramesh Aravind Chamma chamma special appearance with the PLAY Entertainment Sourabh Shrivastava song "Chamma chamma" Bazaar Special appearance with the B4U Entertainment/ Anand Gaurav K. Chawla song "Billionaire" Pandit Motion Pictures Naa Peru Surya, Naa Illu India Special appearance with the Ramalakshmi Cine Creations Vakkantham Vamsi song "Iraga Iraga" The Great Indian Laughter Comedy TV-show: The host Viniyard films/ Star Plus TV Simaab Hashmi, Simaab Challenge Hashmi, Anuupam Purohit Poster Boys Special appearance with the Sony Pictures Networks Shreyas Talpade song "Kudiyan Shehar Diyan" Productions Sida 1/4 Naam Shabana Sona (Cameo) Friday Filmworks Shivam Nair Comedy Nights with Kapil (TV- Star Guest SOL Productions Bharat Kukreti show) Skavlan (TV-talksow) Star guest Monkberry Daniel Jelinek Kis Kisko Pyaar Karoon Leading role: Deepika Kothari Venus/ V One Entertainment Abbas-Mustan Punj Big Boss 7 (reality TV) Elli A Sony Pictures Networks Ankur Poddar, Deepak Dhar, Kapil Batra, Shounok Ghosh Mickey Virus Leading role: Kamayani Dar motion picture Saurabh Varma Förbjuden Frukt Leading role: Selen Ali Alex -

March 30, 2017

THURSDAY 30 MARCH 2017 CAMPUS | 4 HEALTH | 8 BOLLYWOODWOOD | 1111 DPS-MIS attends Marathon running Manoj Bajpayee ‘DIAMUN 2017’ may cause kidney expresses displeasure conference in Dubai injury about the world Email: [email protected] HERITAGE MEETS ART ‘Heritage, Art and Embroidery’, a three-day exhibition held in Doha, showcased the rich Palestinian heritage. It featured the works of Inaash Association from Lebanon and it was sponsored by SIIL. P | 2-3 02 COVER STORY THURSDAY 30 MARCH 2017 The Peninsula he amazing art of cross stitch- ing to create table cloths, wall Expo showcases rich Thangings or portraits has a rich heritage of its own. The cen- tury-old unique Palestinian embroidery also holds a rich tradi- tional heritage and for the first time Palestinian heritage an outstanding exhibition of hand- made embroidery designs combining the wealthy Palestinian heritage and art was held in Doha recently. ‘Heritage, Art and Embroidery’, the three-day exhibition at the May- saloun Hall, Gate Mall, under the auspices of Salam International Investment Limited (SIIL), a lead- ing Doha based conglomerate with a reach across the GCC, Oman, Leb- anon, Jordan and Palestine, featured the dazzling works by the Inaash Association from Lebanon. Founded in 1969, Inaash Asso- ciation provides employment for craftsmanship and is considered to hosting the exhibition to reflect the mere glance one woman could dif- Palestinian refugee women through be a leader in its field. art and artistry of Palestinian ferentiate herself from another by the preservation and promotion of Itself the inheritor of a rich, over embroidery over more than a cen- the patterns on her dress. -

Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the 'Muslim' Courtesan (Tawaif) in Hindustani Cinema

DOCTORAL DISSERTATIO Beneath the Red Dupatta: an Exploration of the Mythopoeic Functions of the ‘Muslim’ Courtesan (tawaif) in Hindustani cinema Farhad Khoyratty Supervised by Dr. Felicity Hand Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanística Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Methodology & Literature Review 5 2.1 Methodology 5 2.2 Towards Defining Hindustani Cinema and Bollywood 9 2.3 Gender 23 2.3.1 Feminism: the Three Waves 23 2.4 Feminist Film Theory and Laura Mulvey 30 2.5 Queer Theory and Judith Butler 41 2.6 Discursive Models for the Tawaif 46 2.7 Conclusion 55 3. The Becoming of the Tawaif 59 3.1 The Argument 59 3.2 The Red Dupatta 59 3.3 The Historical Tawaif – the Past’s Present and the Present’s Past 72 3.4 Geisha and Tawaif 91 4. The Courtesan in the Popular Hindustani cinema: Mapping the Ethico-Ideological and Mythopoeic Space She Occupies 103 4.1 The Argument 103 4.2 Mythopoeic Functions of the Tawaif 103 4.3 The ‘Muslim’ Courtesan 120 4.4 Agency of the Tawaif 133 ii 4.5 Conclusion 147 5. Hindustani cinema Herself: the Protean Body of Hindustani cinema 151 5.1 The Argument 151 5.2 Binary Narratives 151 5.3 The Politics of Kissing in Hindustani Cinema 187 5.4 Hindustani Cinema, the Tawaif Who Seeks Respectability 197 Conclusion 209 Bibliography 223 Filmography 249 Webography 257 Photography 261 iii Dedicated to My Late Father Sulliman For his unwavering faith in all my endeavours It is customary to thank one’s supervisor and sadly this has become such an automatic tradition that I am lost for words fit enough to thank Dr. -

Iifa Awards 2011 Popular Awards Nominations

IIFA AWARDS 2011 POPULAR AWARDS NOMINATIONS BEST FILM MUSIC DIRECTION ❑ Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Salim - Sulaiman — Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Dabangg ❑ Sajid - Wajid & Lalit Pandit — Dabangg ❑ My Name Is Khan ❑ Vishal - Shekhar — I Hate Luv Storys ❑ Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Vishal Bhardwaj — Ishqiya ❑ Raajneeti ❑ Shankar Ehsaan Loy — My Name Is Khan ❑ Pritam — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai BEST DIRECTION ❑ Maneesh Sharma — Band Baaja Baaraat BEST STORY ❑ Abhinav Kashyap — Dabangg ❑ Maneesh Sharma — Band Baajaa Baaraat ❑ Sanjay Leela Bhansali — Guzaarish ❑ Abhishek Chaubey — Ishqiya ❑ Karan Johar — My Name Is Khan ❑ Shibani Bhatija — My Name Is Khan ❑ Milan Luthria — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Rajat Aroraa — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Vikramaditya Motwane — Udaan ❑ Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane — Udaan PERFORMANCE IN A LEADING ROLE: MALE LYRICS ❑ Salman Khan — Dabangg ❑ Amitabh Bhattacharya — Ainvayi Ainvayi, Band Baajaa Baraat ❑ Hrithik Roshan — Guzaarish ❑ Faaiz Anwar — Tere Mast Mast, Dabangg ❑ Shah Rukh Khan — My Name Is Khan ❑ Gulzar — Dil Toh Bachcha, Ishqiya ❑ Ajay Devgn — Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai ❑ Niranjan Iyengar — Sajdaa, My Name Is Khan ❑ Ranbir Kapoor — Raajneeti ❑ Irshad Kamil — Pee Loon, Once Upon A Time In Mumbaai PERFORMANCE IN A LEADING ROLE: FEMALE PLAYBACK SINGER: MALE ❑ Anushka Sharma — Band Baaja Baaraat ❑ Vishal Dadlani — Adhoore, Break Ke Baad ❑ Kareena Kapoor — Golmaal 3 ❑ Rahat Fateh Ali Khan — Tere Mast Mast Do Nain, Dabangg ❑ Aishwarya Rai Bachchan — Guzaarish ❑ Shafqat Amanat Ali — Bin Tere, I Hate -

Education 31 3.1

CONTENTS PRESENTATION 4 1. INSTITUTIONAL 7 1.1. BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE CASA DE LA INDIA FOUNDATION 7 1.2. COUNCIL OF HONOUR 8 1.3. FRIENDS AND BOARD OF FRIENDS OF CASA DE LA INDIA 8 1.4. INSTITUTIONAL EVENTS 9 1.5. INSTITUTIONAL COLLABORATIONS WITH OTHER ORGANISATIONS 13 1.6. AGREEMENTS 13 1.7. GRANTS 14 1.7.1. GRANTS AND INTERNSHIPS AT CASA DE LA INDIA 14 1.7.2. SCHOLARSHIPS FROM THE INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS (ICCR) OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 15 1.8. VIRTUAL PLATFORM INDIANET.ES 15 2. CULTURE 17 2.1. EXHIBITIONS 17 2.1.1. EXHIBITIONS AT CASA DE LA INDIA 17 2.1.2. EXHIBITIONS AT THE IX BIENNIAL HERITAGE RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT FAIR - AR&PA 2014 20 2.2. CINEMA 22 2.2.1. FILM CYCLES 22 2.2.2. OTHER SCREENINGS AT CASA DE LA INDIA 23 2.2.3. SCREENINGS IN OTHER CITIES 24 2.3. PERFORMING ARTS AND MUSIC 24 2.3.1. III INDIA IN CONCERT FESTIVAL 24 2.3.2. OTHER PERFORMANCES 25 2.3.3. COLLABORATION IN PROJECT "SPAIN-INDIA PLATFORM FOR THE PROMOTION AND DISSEMINATION OF CULTURAL INDUSTRIES 27 2.4. BOOK PRESENTATIONS 29 3. EDUCATION 31 3.1. COURSES 31 3.1.1. KALASANGAM. PERMANENT PERFORMING ARTS AND MUSIC SEMINAR 31 3.2. LECTURES, ROUND TABLES AND WORKSHOPS 33 3.2.1. LECTURES, ROUND TABLES AND WORKSHOPS IN CASA DE LA INDIA 33 3.2.2. LECTURES AND WORKSHOPS AT OTHER INSTITUTIONS 34 3.3. ESCUELA DE LA INDIA PROGRAMMES 37 3.3.1. -

Film Kache Dhage Songs Download

1 / 2 Film Kache Dhage Songs Download Watch Saif Ali Khan & Namrata Shirodhkar in the song 'Ek Jawani Teri Ek Jawani Meri' from the movie 'Kachche Dhaage'.sung by Alka Yagnik & Kumar Sanu .. Kachche Dhaage (1999) Mp3 Songs Download, K Mp3 Songs Kachche Dhaage (1999) Mp3 Songs, Listen, Mp3 Song Download, Mp3 Song.. Kachche,,Dhaage,,1999,,|,,Download,,Bollywood,,Movie,,Mp3,,Songs sabsongs.net/bollywood/kachche-dhaage-1999-songs-download.html. Bollywood,,Movies .... India film is produced under the banner of and distributed by Tips Music Films. Kachche Dhaage movie Direct Songs Download on mr-jatt Original Rip. The first .... Nov 22, 2018 — Kachche Dhaage Mp3 Songs Download , www.SongAction.In http://www.songaction.in/movie/kachche-dhaage-mp3-songs- download/- .... कच्चे धागे || Super hit Full Bhojpuri Movie || Kachche Dhaage || Khesari Lal Yadav - Bhojpuri Film. Wave Music. Play - Download. Khaali Dil Hai Jaan .... Download kachche dhaage full songs mp3 download ajay devgan manisha koirala ... Raj khosla enjoy this super hit song from the 1973 movie kachche dhaage ... Film, Kachche Dhaage. Release Date, 19th February, 1999. Director, Milan Luthria. Star Cast, Ajay Devgn, Saif Ali Khan, Manisha Koirala, Namrata Shirodkar, .... Bestselling bollywood music album of movie 'Gupt' is now in the form of Audio Jukebox. Enjoy watching the soulful 'Tere Bin Nahin Jeena Mar Jana', also sung as .... Ajay Devgn, Saif Ali Khan, and Manisha Koirala in Kachche Dhaage (1999) ... But Ajay- Saif chase scenes are well handled and entertaining sadly the film goes ... to scene Direction by Milan Luthria is average to below average Music is okay. Download Kachche Dhaage High Quality Mp3 Songs.Kachche Dhaage Is directed by Milan Luthria and its Music Director is Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. -

LIST of HINDI CINEMA AS on 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days

LIST OF HINDI CINEMA AS ON 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days/ Directed by- Partho Ghosh Class No : 100 HFC Accn No. : FC003137 Location : gsl 2 Title : 15 Park Avenue Class No : FIF HFC Accn No. : FC001288 Location : gsl 3 Title : 1947 Earth Class No : EAR HFC Accn No. : FC001859 Location : gsl 4 Title : 27 Down Class No : TWD HFC Accn No. : FC003381 Location : gsl 5 Title : 3 Bachelors Class No : THR(3) HFC Accn No. : FC003337 Location : gsl 6 Title : 3 Idiots Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC001999 Location : gsl 7 Title : 36 China Town Mn.Entr. : Mustan, Abbas Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001100 Location : gsl 8 Title : 36 Chowringhee Lane Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001264 Location : gsl 9 Title : 3G ( three G):a killer connection Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC003469 Location : gsl 10 Title : 7 khoon maaf/ Vishal Bharadwaj Film Class No : SAA HFC Accn No. : FC002198 Location : gsl 11 Title : 8 x 10 Tasveer / a film by Nagesh Kukunoor: Eight into ten tasveer Class No : EIG HFC Accn No. : FC002638 Location : gsl 12 Title : Aadmi aur Insaan / .R. Chopra film Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002409 Location : gsl 13 Title : Aadmi / Dir. A. Bhimsingh Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002640 Location : gsl 14 Title : Aag Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC001678 Location : gsl 15 Title : Aag Mn.Entr. : Raj Kapoor Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC000105 Location : MSR 16 Title : Aaj aur kal / Dir. by Vasant Jogalekar Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. : FC002641 Location : gsl 17 Title : Aaja Nachle Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No.