The Development and Improvement of Instructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economist Was a Workhorse for the Confederacy and Her Owners, the Trenholm Firms, John Fraser & Co

CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM Nassau, Bahamas (Illustrated London News Feb. 10, 1864) By Ethel Nepveux During the war, the Economist was a workhorse for the Confederacy and her owners, the Trenholm firms, John Fraser & Co. of Charleston, South Carolina, and Fraser, Trenholm & Co. of Liverpool, England, and British Nassau and Bermuda. The story of the ship comes from bits and pieces of scattered information. She first appears in Savannah, Georgia, where the Confederate network (conspiracy) used her in their efforts to obtain war materials of every kind from England. President Davis sent Captain James Bulloch to England to buy an entire navy. Davis also sent Caleb Huse to purchase armaments and send them back home. Both checked in to the Fraser, Trenholm office in Liverpool which gave them office space and the Trenholm manager Charles Prioleau furnished credit for their contracts and purchases. Neither the men nor their government had money or credit. George Trenholm (last Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederacy) bought and Prioleau loaded a ship, the Bermuda, to test the Federal blockade that had been set up to keep the South from getting supplies from abroad. They sent the ship to Savannah, Georgia, in September 1861. The trip was so successful that the Confederates bought a ship, the Fingal. Huse bought the cargo and Captain Bulloch took her himself to Savannah where he had been born and was familiar with the harbor. The ship carried the largest store of armaments that had ever crossed the ocean. Bulloch left all his monetary affairs in the hands of Fraser, Trenholm & Co. -

Boxoffice Records: Season 1937-1938 (1938)

' zm. v<W SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL JANET DOUGLAS PAULETTE GAYNOR FAIRBANKS, JR. GODDARD in "THE YOUNG IN HEART” with Roland Young ' Billie Burke and introducing Richard Carlson and Minnie Dupree Screen Play by Paul Osborn Adaptation by Charles Bennett Directed by Richard Wallace CAROLE LOMBARD and JAMES STEWART in "MADE FOR EACH OTHER ” Story and Screen Play by Jo Swerling Directed by John Cromwell IN PREPARATION: “GONE WITH THE WIND ” Screen Play by Sidney Howard Director, George Cukor Producer DAVID O. SELZNICK /x/HAT price personality? That question is everlastingly applied in the evaluation of the prime fac- tors in the making of motion pictures. It is applied to the star, the producer, the director, the writer and the other human ingredients that combine in the production of a motion picture. • And for all alike there is a common denominator—the boxoffice. • It has often been stated that each per- sonality is as good as his or her last picture. But it is unfair to make an evaluation on such a basis. The average for a season, based on intakes at the boxoffices throughout the land, is the more reliable measuring stick. • To render a service heretofore lacking, the publishers of BOXOFFICE have surveyed the field of the motion picture theatre and herein present BOXOFFICE RECORDS that tell their own important story. BEN SHLYEN, Publisher MAURICE KANN, Editor Records is published annually by Associated Publica- tions at Ninth and Van Brunt, Kansas City, Mo. PRICE TWO DOLLARS Hollywood Office: 6404 Hollywood Blvd., Ivan Spear, Manager. New York Office: 9 Rockefeller Plaza, J. -

Address by the Honorable Edward H. Levi, Attorney General of the United

ADDRESS BY THE HONORABLE EDWARD H. LEVI ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES AT THE DEDICATION CEREMONIES OF THE JOHN EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING 11:00 A.M. TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 1975 J. EDGAR HOOVER BUILDING WASHINGTON, D. C. We have come together to dedicate this new building as the headquarters of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It is a proper moment to look back to the tradition of this law enforcement organization as well as to look forward to t.he future it will meet in this new place. It was under Theodore Roosevelt that the predecessor of the FBI was founded. There was resistance to its creation. For varied reasons -- noble and base -- some feared the idea of a federal' criminal investigative agency within the Justice Department. But through'the persistence of Attorney General Charles Joseph Bonaparte the organization was formed. The resistance did not crumble when Bonaparte's idea was accompli-shed. There were bad years to follow for the Bureau. It did not escape the tarnish of the Teapot Dome era. The Justice Department and the Bureau were criticized for failing to attack official corruption with sufficient vigor. From this period the' Bureau emerged with a new beginning under the man to whose memory this new building is dedicated. John Edgar Hoover was 29 years old when Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone appointed him acting director of the Bureau in May of 1924. Hoover's reputation of scrupulous honesty had been commended to Stone. Such a man was needed. Hoover set about reforming the Bureau to meet the demanding requirements of a more complicated era. -

Art in Wartime

Activity: Saving Art during Wartime: A Monument Man’s Mission | Handouts Art in Wartime: Understanding the Issues At the age of 37, Walter Huchthausen left his job as a professor at the University of Minnesota and a designer and architect of public buildings to join the war efort. Several other artists, architects, and museum person- nel did the same. In December 1942, the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Francis Taylor, heard about the possibility of serving on a team of specialists to protect monuments in war zones. He wrote : “I do not know yet how the Federal Government will decide to organize this, but one thing is crystal clear; that we will be called upon for professional service, either in civilian or military capacity. I personally have ofered my services, and am ready for either.” Do you think it was a good use of U.S. resources to protect art? What kinds of arguments could be advanced for and against the creation of the MFAA? Arguments for the creation of the MFAA: Arguments against the creation of the MFAA: Walter Huchthausen lost his life trying to salvage an altarpiece in the Ruhr Valley, Germany. What do you think about the value of protecting art and architecture in comparison to the value of protecting a human life? Arguments for use of human lives to protect art during war: ABMCEDUCATION.ORG American Battle Monuments Commission | National History Day | Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media Activity: Saving Art during Wartime: A Monument Man’s Mission | Handouts Arguments against the use of human lives to protect art during war: Germany had purchased some of the panels of the famous Ghent altarpiece (above) before World War I, then removed other panels during its occupation of Belgium in World War I. -

John Steel, Artist of the Underwater World

Historical Diver, Number 19, 1999 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 23/09/2021 12:48:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30862 NUMBER 19 SPRING 1999 John Steel, Artist of the Underwater World Salvage Man - The Career of Edward Ellsberg • Sicard's 1853 Scuba Apparatus Underwater Photography 1935 • Lambertsen Gas Saver Unit • Lang Helmet • NOGI Awards ADC Awards • D.E.M.A. Awards • Carol Ann Merker • Beneath the Sea Show HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA A PUBLIC BENEFIT NON-PROFIT CORPORATION PMB 405 2022 CLIFF DRIVE SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA 93109-1506, U.S.A. PHONE: 805-692-0072 FAX: 805-692-0042 e-mail: [email protected] or HTTP://WWW.hds.org/ ADVISORY BOARD CORPORATE MEMBERS Dr. Sylvia Earle Lotte Hass DIVERS ALERT NETWORK Dr. Peter B. Bennett Dick Long STOLT COMEX SEAWAY Dick Bonin J. Thomas Millington, M.D. OCEAN FUTURES Scott Carpenter Bob & Bill Meistrell OCEANIC DIVING SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL Jean-Michel Cousteau Bev Morgan D.E.S.C.O. E.R. Cross Phil Nuytten SCUBA TECHNOLOGIES, INC. Andre Galerne Sir John Rawlins DIVE COMMERCIAL INTERNATIONAL, INC. Lad Handelman Andreas B. Rechnitzer, Ph.D. MARES Prof. Hans Hass Sidney J. Smith SEA PEARLS CALDWELL'S DIVING CO. INC. Les Ashton Smith OCEANEERING INTL. INC. WEST COAST SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS DRS MARINE, INC. Chairman: Lee Selisky, President: Leslie Leaney, Secretary: AQUA-LUNG James Forte, Treasurer: Blair Mott, Directors: Bonnie W.J. CASTLE P.E. & ASSOC.P.C. Cardone, Angela Tripp, Captain Paul Linaweaver, M.D., MARINE SURPLUS SUPPLY BEST PUBLISHING U.S.N. -

1905-1906 Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University

OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during: the Academical Year ending in JUNE, /9O6, INCLUDING THE RECORD OF A FEW WHO DIED PREVIOUSLY, HITHERTO UNREPORTED [Presented at the meeting of the Alumni, June 26, 1906] [No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] OBITUARY RECORD OF GRADUATES OF YALE UNIVERSITY Deceased during the Academical year ending in JUNE, 1906 Including the Record of a few who died previously, hitherto unreported [PRESENTED AT THE MEETING OF THE ALUMNI, JUNE 26, 1906] I No 6 of the Fifth Printed Series, and No 65 of the whole Record] YALE COLLEGE (ACADEMICAL DEPARTMENT) 1831 JOSEPH SELDEN LORD, since the death of Professor Samuel Porter of the Class of 1829, m September, 1901, the oldest living graduate of^Yale University, and since the death of Bishop Clark m September, 1903, the last survivor of his class, was born in Lyme, Conn, April 26, 1808. His parents were Joseph Lord, who carried on a coasting trade near Lyme, and Phoebe (Burnham) Lord. He united with the Congregational church m his native place when 16 years old, and soon began his college preparation in the Academy of Monson, Mass., with the ministry m view. Commencement then occurred in September, and after his graduation from Yale College, he taught two years in an academy at Bristol, Conn He then entered the Yale Divinity School, was licensed to preach by the Middlesex Congregational Association of Connecticut in 1835, and completed his theological studies in 1836. After supplying 522 the Congregational church in -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

Review by Howard J. Fuller University of Wolverhampton Department of War Studies

A Global Forum for Naval Historical Scholarship International Journal of Naval History August 2009 Volume 8 Number 2 Ari Hoogenboom, Gustavus Vasa Fox of the Union Navy: A Biography. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. 408 pp. 9 halftones, 10 line drawings. Review by Howard J. Fuller University of Wolverhampton Department of War Studies ________________________________________________________________________ Over a thousand pages long, the 1896 Naval History of the United States, by Willis J. Abbot, typically does not even mention Fox. “The story of the naval operations of the civil war is a record of wonderful energy and inventive skill in improving and building war vessels,” the story goes, and by the end of the conflict “the navy of the United States consisted of six hundred and seventy-one vessels. No nation of the world had such a naval power. The stern lessons of the great war had taught shipbuilders that wooden ships were a thing of the past. The little ‘Monitor’ had by one afternoon’s battle proved to all the sovereigns of Europe that their massive ships were useless,” (685-7). Of course the perception here is deterministic; it was a matter of American ‘destiny’ that the North would triumph, or even that the Union Navy would become a leading ironclad power—whatever that meant. Heroic naval admirals like Farragut, Porter and Du Pont seemed to operate under orders issued from behind a mysterious curtain back in Washington, D.C. We don’t see those hidden, historic actors who actually designed and launched the fine naval force Union officers wielded throughout the Civil War (often with mixed results). -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

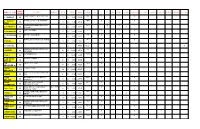

Name of Plan Wing Span Details Source Area Price Ama Ff Cl Ot Scale Gas Rubber Electric Other Glider 3 View Engine Red. Ot C

WING NAME OF PLAN DETAILS SOURCE AREA PRICE AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE RED. OT SPAN COMET MODEL AIRPLANE CO. 7D4 X X C 1 PURSUIT 15 3 $ 4.00 33199 C 1 PURSUIT FLYING ACES CLUB FINEMAN 80B5 X X 15 3 $ 4.00 30519 (NEW) MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 1/69, 90C3 X X C 47 PROFILE 35 SCHAAF 5 $ 7.00 31244 X WALT MOONEY 14F7 X X X C A B MINICAB 20 3 $ 4.00 21346 C L W CURLEW BRITISH MAGAZINE 6D6 X X X 15 2 $ 3.00 20416 T 1 POPULAR AVIATION 9/28, POND 40E5 X X C MODEL 24 4 $ 5.00 24542 C P SPECIAL $ - 34697 RD121 X MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 4/42, 8A6 X X C RAIDER 68 LATORRE 21 $ 23.00 20519 X AEROMODELLO 42D3 X C S A 1 38 9 $ 12.00 32805 C.A.B. GY 20 BY WALT MOONEY X X X 20 4 $ 6.00 36265 MINICAB C.W. SKY FLYER PLAN 15G3 X X HELLDIVER 02 15 4 $ 5.00 35529 C2 (INC C130 H PLAMER PLAN X X X 133 90 $ 122.00 50587 X HERCULES QUIET & ELECTRIC FLIGHT INT., X CABBIE 38 5/06 6 $ 9.00 50413 CABIN AEROMODELLER PLAN 8/41, 35F5 X X 20 4 $ 5.00 23940 BIPLANE DOWNES CABIN THE OAKLAND TRIBUNE 68B3 X X 20 3 $ 4.00 29091 COMMERCIAL NEWSPAPER 1931 Indoor Miller’s record-holding Dec. 1979 X Cabin Fever: 40 Manhattan Cabin. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Celebrating the Centennial of Naval Aviation in 1/72 Scale

Celebrating the Centennial of Naval Aviation in 1/72 Scale 2010 USN/USMC/USCG 1/72 Aircraft Kit Survey J. Michael McMurtrey IPMS-USA 1746 Carrollton, TX [email protected] As 2011 marks the centennial of U.S. naval aviation, aircraft modelers might be interested in this list of US naval aircraft — including those of the Marines and Coast Guard, as well as captured enemy aircraft tested by the US Navy — which are available as 1/72 scale kits. Why 1/72? There are far more kits of naval aircraft available in this scale than any other. Plus, it’s my favorite, in spite of advancing age and weakening eyes. This is an updated version of an article I prepared for the 75th Anniversary of US naval aviation and which was published in a 1986 issue of the old IPMS-USA Update. It’s amazing to compare the two and realize what developments have occurred, both in naval aeronautical technology and the scale modeling hobby, but especially the latter. My 1986 list included 168 specific aircraft types available in kit form from thirty- three manufacturers — some injected, some vacuum-formed — and only three conversion kits and no resin kits. Many of these names (Classic Plane, Contrails, Eagle’s Talon, Esci, Ertl, Formaplane, Frog, Griffin, Hawk, Matchbox, Monogram, Rareplane, Veeday, Victor 66) are no longer with us or have been absorbed by others. This update lists 345 aircraft types (including the original 168) from 192 different companies (including the original 33), many of which, especially the producers of resin kits, were not in existence in 1986, and some of which were unknown to me at the time.