Self Study 12/30/04 Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory,Ritual and Place in Africa TWIN CITIES AFRICANIST SYMPOSIUM

Sacred Ground: Memory,Ritual and Place in Africa TWIN CITIES AFRICANIST SYMPOSIUM Carleton College February 21-22, 2003 Events Schedule Friday, February 21 Great Hall, 4 to 9 p.m. Welcoming Remarks Allen Isaacman, University of Minnesota Keynote Lecture “The Politics and Poetics of Sacred Sites” Sandra Greene, Professor of History, Cornell University 4 to 6 p.m. Reception with African Food, Live Music Musical performance by Jalibah Kuyateh and the Mandingo Griot Ensemble 6 to 9 p.m. Saturday, February 22 Alumni Guest House Meeting Room Morning panel: 9 to 10:30 a.m. Theme: Sacred Ground: Memory, Ritual and Place in Africa Chair: Sandra Greene, Cornell University William Moseley, Department of Geography, Macalester College, “Leaving Hallowed Practices for Hollow Ground: Wealth, Poverty and Cotton Production in Southern Mali” Kathryn Linn Geurts, Department of Anthropology, Hamline University, “Migration Myths, Landscape, and Cultural Memory in Southeastern Ghana” Jamie Monson, Department of History, Carleton College, “From Protective Lions to Angry Spirits: Local Discourses of Land Degradation in Tanzania” Cynthia Becker, Department of Art History, University of St. Thomas, “Zaouia: Sacred Space, Sufism and Slavery in the Trans-Sahara Caravan Trade” Coffee Break Mid-Morning panel: 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Theme: Memory, Ritual and Performance in Africa Chair: Dianna Shandy, Macalester College Michele Wagner, Department of History, University of Minnesota, “Reburial in Rwanda: Ritual of Healing or Ritual of Revenge?” Tommie Jackson, Department of English, St. Cloud State University, “‘Fences’ in the drama by August Wilson and ‘Sizwe Bansi is Dead,’ by Athol Fugard” Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, Department of History, University of Minnesota, “Memory and Violence in Soweto” Pamela Feldman-Savelsberg, Department of Anthropology, Carleton College, “Remembering the Troubles: Collective Memory and Reproduction in Cameroon” Break 12:30 to 2 p.m. -

Lawrence University (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) at Beloit College (1-1, 0-0

Lawrence University (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) at Beloit College (1-1, 0-0 MWC North) Saturday, September 19, 2015, 1 p.m., Strong Stadium, Beloit, Wisconsin Webcast making his first start, was 23-for-36 ing possession and moved 75 yards A free video webcast is available for 274 yards and three touchdowns. in 12 plays for the game’s first touch- at: http://portal.stretchinternet.com/ Mandich, a senior receiver from Green down. Byrd hit freshman receiver and lawrence/. Bay, had a career-high eight catches Appleton native Cole Erickson with an for 130 yards and a touchdown for the eight-yard touchdown pass to com- The Series Vikings. plete the drive and give Lawrence a Lawrence holds a 58-36-5 edge in The Lawrence defense limited 7-3 lead. a series that dates all the way back to Beloit to 266 yards and made a key The Vikings then put together 1899. This year marks the 100th game stop late in the game to preserve the another long scoring drive early in in the series, which is the second- victory. Linebacker Brandon Taylor the second quarter. Lawrence went longest rivalry for Lawrence. The Vi- paced the Lawrence defense with 14 80 yards in eight plays and Byrd found kings have played 114 games against tackles and two pass breakups. Trevor Spina with a 24-yard touch- Ripon, and that series dates to 1893. Beloit was down by eight but got down pass for a 14-3 Lawrence lead Lawrence has won three of the last an interception on a tipped ball and with 11:53 left in the first half. -

Below Is a Sampling of the Nearly 500 Colleges, Universities, and Service Academies to Which Our Students Have Been Accepted Over the Past Four Years

Below is a sampling of the nearly 500 colleges, universities, and service academies to which our students have been accepted over the past four years. Allegheny College Connecticut College King’s College London American University Cornell University Lafayette College American University of Paris Dartmouth College Lehigh University Amherst College Davidson College Loyola Marymount University Arizona State University Denison University Loyola University Maryland Auburn University DePaul University Macalester College Babson College Dickinson College Marist College Bard College Drew University Marquette University Barnard College Drexel University Maryland Institute College of Art Bates College Duke University McDaniel College Baylor University Eckerd College McGill University Bentley University Elon University Miami University, Oxford Binghamton University Emerson College Michigan State University Boston College Emory University Middlebury College Boston University Fairfield University Morehouse College Bowdoin College Florida State University Mount Holyoke College Brandeis University Fordham University Mount St. Mary’s University Brown University Franklin & Marshall College Muhlenberg College Bucknell University Furman University New School, The California Institute of Technology George Mason University New York University California Polytechnic State University George Washington University North Carolina State University Carleton College Georgetown University Northeastern University Carnegie Mellon University Georgia Institute of Technology -

APRIL 2020 Newsletter

Submissions from the t- shirt design contest are Read about future plans in! Check them out on for some of the class of page 4! 2020 in the Senior Spotlights on pages 7-8! ST. OLAF COLLEGE TRIO Upward Bound Messenger March/April 2020 Volume XXXI Issue #6 wp.stolaf.edu/upward/ UB Reminders and Updates By: Mari Avaloz Although spring is generally a time we will focus on math and science start thinking about graduation, BBQs homework help and are available to and living at Olaf for the summer, we you for the remainder of the school seem to remain in a time of year. uncertainty. UB staff also feel the same and miss seeing our students in UB Summer Program person, but we are thankful for their continued dedication to the program. UB is here to remind students to SP The most up-to-date information and remember, this too will pass. about summer is detailed in the letter th Don’t lose motivation to finish the sent on April 10 . Students, please school year strong, and look forward keep up with your email regarding In This Issue: to the time we can unite again. It will updates about summer. Parents/ happen. This article highlights a few guardians, we will send more info of our most recent updates (more once we lock down more specifics. UB SPIRIT WEEK . page 2 details can be found in the letter sent Please feel free to call UB with any to participants on April 10, 2020). additional questions or concerns. WELCOME NEW STUDENTS! . -

Fall 2019 College Visits Users' Guide

Fall 2019 College Visits Users’ Guide Providence Academy College Counseling Disclaimer: The descriptions in this guide have been formed from the combined experience of PA’s college counselors, input from admission representatives, feedback from PA students and graduates, and recognized college guides. This guide does not depict all that there is to know about these campuses, nor does it mention all the strong academic offerings which may be available. We hope it helps you choose visits well and to broaden your college search! REMINDER: To attend college meetings scheduled during the Light Blue or Pink elective periods, students must obtain a college visit pass from Mrs. Peterson at least one day in advance of the visit and then, also at least one day in advance, speak with and obtain the signature of their elective course or study hall instructor . With a signed college visit pass, students may proceed directly to the college meeting at the start of the period. Tuesday, September 24 8:00 AM: University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC) (UBC is a very large, internationally recognized research university that recruits heavily from abroad, which includes recruiting U.S. students to its campus on the edge of the Strait of Georgia in Vancouver, Canada. The massive campus requires considerable independence and self-direction, but the academic programs are widely considered to be first-rate. Prominent programs include computer science, economics, and international relations.) 8:00 AM: Lynn University (Boca Raton, FL) (A private university in Boca Raton, Fla., Lynn enrolls 2,300 undergraduate students and is considered one of the country’s most innovative colleges. -

Lawrence University

Lawrence University a college of liberal arts & sciences a conservatory of music 1425 undergraduates 165 faculty an engaged and engaging community internationally diverse student-centered changing lives a different kind of university 4 28 Typically atypical Lawrentians 12 College should not be a one-size-fits-all experience. Five stories of how Find the SLUG in this picture. individualized learning changes lives (Hint: It’s easy to find if you know at Lawrence. 10 what you’re looking for.) Go Do you speak Vikes! 19 Lawrentian? 26 Small City 20 Music at Lawrence Big Town 22 Freshman Studies 23 An Engaged Community 30 Life After Lawrence 32 Admission, Scholarship & Financial Aid Björklunden 18 29 33 Lawrence at a Glance Find this bench (and the serenity that comes with it) at Björklunden, Lawrence’s 425-acre A Global Perspective estate on Door County’s Lake Michigan shore. 2 | Lawrence University Lawrence University | 3 The Power of Individualized Learning College should not be a one-size-fits-all experience. Lawrence University believes students learn best when they’re educated as unique individuals — and we exert extraordinary energy making that happen. Nearly two- thirds of the courses we teach at Lawrence have the optimal (and rare) student-to-faculty ratio of 1 to 1. You read that correctly: that’s one student working under the direct guidance of one professor. Through independent study classes, honors projects, studio lessons, internships and Oxford-style tutorials — generally completed junior and senior year — students have abundant -

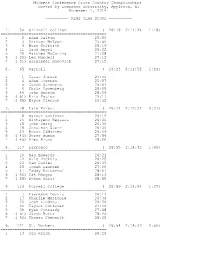

Midwest Conference Cross Country Championships Hosted by Lawrence University, Appleton, WI November 1, 2014 ===MENS TEAM

Midwest Conference Cross Country Championships Hosted by Lawrence University, Appleton, WI November 1, 2014 ========== MENS TEAM SCORE ========== 1. 54 Grinnell College ( 26:19 2:11:34 1:18) ============================================= 1 2 Adam Dalton 25:50 2 3 Anthony McLean 25:55 3 9 Evan Griffith 26:19 4 11 Zach Angel 26:22 5 29 Matthew McCarthy 27:08 6 ( 30) Lex Mundell 27:12 7 ( 31) Alexander Monovich 27:15 2. 65 Carroll ( 26:23 2:11:52 2:29) ============================================= 1 1 Isaac Jordan 25:40 2 4 Adam Joerres 25:57 3 5 Jacob Sundberg 26:01 4 6 Chris Pynenberg 26:05 5 49 Jake Hanson 28:09 6 ( 61) Eric Paulos 29:17 7 ( 65) Bryce Pierson 29:32 3. 78 Lake Forest ( 26:31 2:12:32 0:37) ============================================= 1 8 Mansur Soeleman 26:12 2 14 Sintayehu Regassa 26:26 3 15 John Derry 26:30 4 18 Jonathan Stern 26:35 5 23 Rocco DiMatteo 26:49 6 ( 43) Steve Auman 27:54 7 ( 45) Alec Bruns 28:00 4. 117 Lawrence ( 26:55 2:14:32 1:46) ============================================= 1 10 Max Edwards 26:21 2 12 Kyle Dockery 26:25 3 22 Cam Davies 26:39 4 26 Jonah Laursen 27:00 5 47 Teddy Kortenhof 28:07 6 ( 50) Pat Mangan 28:13 7 ( 55) Ethan Gniot 28:55 5. 119 Cornell College ( 26:59 2:14:54 1:37) ============================================= 1 7 Lawrence Dennis 26:11 2 17 Charlie Mesimore 26:34 3 20 Josh Lindsay 26:36 4 36 Taylor Christen 27:45 5 39 Ryan Conrardy 27:48 6 ( 51) Jacob Butts 28:24 7 ( 52) Thomas Chenault 28:25 6. -

St. Olaf College

National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment September 2020 Assessment in Motion: Steps Toward a More Integrated Model Susan Canon, Kelsey Thompson, and Mary Walczak Olaf College St. Foreword By Pat Hutchings As part of an ongoing effort to track and explore developments in student learning outcomes assessment, the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA) has published a number of institutional case studies which are housed on the website. We are now revisiting and updating some of those earlier examples in order to understand how campus assessment practices evolve over time—through lessons learned from local experience but also as a result of changes in institutional priorities, the launch of new initiatives, leadership transitions, and trends in the larger assessment movement. This report on St. Olaf College is an update of theoriginal 2012 case study by Natasha Jankowski. Founded in 1874 by Norwegian Lutheran immigrants, St. Olaf College is a nationally ranked residential liberal arts college of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) located in Northfield, Minnesota. St. Olaf challenges students to excel in the liberal arts, examine faith and values, and explore meaningful vocation in an inclusive, globally engaged community nourished by Lutheran tradition. St. Olaf has roughly 3,000 students, offers 49 majors and 20 concentrations (minors), and has a robust study-abroad program, with more than two-thirds of students studying abroad before graduating. St. Olaf has a long history with assessment, having participated in many different assessment initiatives over the years including a Teagle-funded project with Carleton College and Macalester College focused on using assessment findings to improve specific learning outcomes, and eth Associated Colleges of the Midwest-Teagle Collegium on Student Learning exploring how students learn and acquire the knowledge and skills of a liberal education. -

The Faculty, of Which He Was Then President

Carleton Moves CoddentJy Into Its Second Century BY MERRILL E. JARCHOW 1992 CARLETON COLLEGE NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA Q COPYRIGHT 1992 BY CARLETON COLLEGE, NORTHFIELD, MINNESOTA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Libray of Congress Curalog Card Number: 92-72408 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Cover: Old and New: Scoville (1895). Johnson Hall (admissions) / Campus Club (under construction) Contents Foreword ...................................................................................vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................xi 1: The Nason Years ........................................................................1 2: The Swearer Years ....................................................................27 3: The Edwards Years ...................................................................69 4: The Porter Year .......................................................................105 5: The Lewis Years ......................................................................121 Epilogue ..................................................................................155 Appendix .................................................................................157 iii Illustrations President John W . Nason and his wife Elizabeth at the time of Carleton's centennial ..................................................2 Isabella Watson Dormitory ...............................................................4 Student Peace March in 1970 ..........................................................15 -

Wheaton College Catalog 2003-2005 (Pdf)

2003/2005 CATALOG WHEATON COLLEGE Norton, Massachusetts www.wheatoncollege.edu/Catalog College Calendar Fall Semester 2003–2004 Fall Semester 2004–2005 New Student Orientation Aug. 30–Sept. 2, 2003 New Student Orientation Aug. 28–Aug. 31, 2004 Labor Day September 1 Classes Begin September 1 Upperclasses Return September 1 Labor Day (no classes) September 6 Classes Begin September 3 October Break October 11–12 October Break October 13–14 Mid-Semester October 20 Mid-Semester October 22 Course Selection Nov. 18–13 Course Selection Nov. 10–15 Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 24–28 Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 26–30 Classes End December 13 Classes End December 12 Review Period Dec. 14–15 Review Period Dec. 13–14 Examination Period Dec. 16–20 Examination Period Dec. 15–20 Residence Halls Close Residence Halls Close (9:00 p.m.) December 20 (9:00 p.m.) December 20 Winter Break and Winter Break and Internship Period Dec. 20 – Jan. 25, 2005 Internship Period Dec. 20–Jan. 26, 2004 Spring Semester Spring Semester Residence Halls Open Residence Halls Open (9:00 a.m.) January 25 (9:00 a.m.) January 27, 2004 Classes Begin January 26 Classes Begin January 28 Mid–Semester March 11 Mid–Semester March 12 Spring Break March 14–18 Spring Break March 15–19 Course Selection April 11–15 Course Selection April 12–26 Classes End May 6 Classes End May 7 Review Period May 7–8 Review Period May 8–9 Examination Period May 9–14 Examination Period May 10–15 Commencement May 21 Commencement May 22 First Semester Deadlines, 2004–2005 First Semester Deadlines, 2003–2004 Course registration -

2014 NSSE Report

Lake Forest College NSSE 2014 Administered in Spring 2014 Report by S. Boyd Institutional Research 1 Introduction Lake Forest College administered the most recent iteration of the NSSE (National Survey of Student Engagement) in the spring of 2014. Previous surveys were given in 2007, 2008, and 2011. This iteration continues the College’s administration of the survey on a three year cycle. The results discussed here compare: • Lake Forest to the NSSE universe, and in particular those schools scoring in the top 10%. • Lake Forest compared to a comparison group of selected liberal arts colleges and universities who responded to the NSSE in 2013 and 2014. Generally, engagement indicator scores were very favorable for first-years and seniors. First-years compared well to the NSSE Top 10% group on 9 out of 10 indicators. Seniors compared well to the NSE Top 10% group on 2 out of 10 indicators. What is NSSE? NSSE is administered nationally. In 2014, 713 schools participated in the survey. Extract from the NSSE 2014 Overview: “The National Survey of Student Engagement collected information annually from first-year and senior students about the characteristics and quality of their undergraduate experience. Since the inception of the survey, nearly 1,500 bachelor’s-granting colleges and universities in the United States and Canada have used it to measure the extent to which students engage in effective educational practices that are empirically linked with learning, personal development, and other desired outcomes such as persistence, satisfaction, and graduation. NSSE data are used by faculty, administrators, research and others for institutional improvement, accountability, and related purposes.” The survey is administered over the Web to volunteers in the first year and senior class. -

GRADUATE PROGRAM in the HISTORY of ART Williams College/Clark Art Institute

GRADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF ART Williams College/Clark Art Institute Summer 2003 NEWSLETTER The Class of 2003 at its Hooding Ceremony. Front row, from left to right: Pan Wendt, Elizabeth Winborne, Jane Simon, Esther Bell, Jordan Kim, Christa Carroll, Katie Hanson; back row: Mark Haxthausen, Ben Tilghman, Patricia Hickson, Don Meyer, Ellery Foutch, Kim Conary, Catherine Malone, Marc Simpson LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR CHARLES w.: (MARK) HAxTHAUSEN Faison-Pierson-Stoddard Professor of Art History, Director of the Graduate Program With the 2002-2003 academic year the Graduate Program began its fourth decade of operation. Its success during its first thirty years outstripped the modest mission that shaped the early planning for the program: to train for regional colleges art historians who were drawn to teaching careers yet not inclined to scholarship and hence having no need to acquire the Ph.D. (It was a different world then!) Initially, those who conceived of the program - members of the Clark's board of trustees and Williams College President Jack Sawyer - seem never to have imagined that it would attain the preeminence that it quickly achieved under the stewardship of its first directors, George Heard Hamilton, Frank Robinson, and Sam Edgerton. Today the Williams/Clark program enjoys an excellent reputation for preparing students for museum careers, yet this was never its declared mission; unlike some institutions, we have never offered a degree or even a specialization in "museum studies" or "museology." Since the time of George Hamilton, the program has endeavored simply to train art historians, and in doing so it has assumed that intimacy with objects is a sine qua non for the practice of art history.