Why Washington, DC Airspace Restrictions Do Not Enhance Security John W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

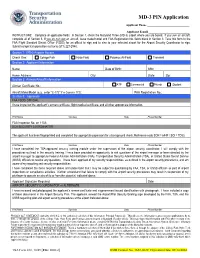

MD-3 PIN Application

MD-3 PIN Application Applicant Phone Applicant E-mail INSTRUCTIONS: Complete all applicable fields. In Section 1, check the Maryland Three (MD-3) airport where you are based. If you own an aircraft, complete all of Section 3. If you do not own an aircraft, leave make/model and FAA Registration No. fields blank in Section 3. Take this form to the FAA Flight Standard District Office (FSDO) for an official to sign and to also to your selected airport for the Airport Security Coordinator to sign. Submit completed application via fax to (571) 227-2948. Section 1: MD-3 Airports Access Check One: College Park Hyde Field Potomac Air Field Transient Section 2: Applicant Information Name: Date of Birth: SSN: Home Address: City: State: Zip: Section 3: Airman/Aircraft Information Airman Certificate No.: ATP Commercial Private Student Aircraft Make/Model (e.g., enter “C-172” if a Cessna 172): FAA Registration No.: Section 3: Approvals FAA FSDO OFFICIAL I have inspected the applicant’s airman certificate, flight medical certificate, and all other appropriate information. Print Name Signature Date Phone Number FAA Inspector No. on 110A: DCA SECURITY COORDINATOR The applicant has been fingerprinted and completed the appropriate paperwork for a background check. Reference code SON = 644F / SOI = TD30. Print Name Signature Date Phone Number I have completed the TSA-approved security training module under the supervision of the airport security coordinator. I will comply with the procedures outlined in the security training. I have been provided an opportunity to ask questions of the airport manager or been directed by the airport manager to appropriate Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Transportation Security Administration (TSA), or United States Secret Service (USSS) officials to resolve any questions. -

Table of Contents.Pdf

Prince George’s County Planning Department Airport Compatibility Planning Project The Prince George’s County Planning Department has been engaged in a work program effort to examine risk and land use compatibility issues around the county’s four general aviation airports: Potomac Airfield in Friendly, Washington Executive Airpark in Clinton, Freeway Airport in Mitchellville, and College Park Airport in College Park. The project is an outgrowth of several aircraft accidents in the neighborhoods close to Potomac Airfield during the mid-1990s and resulting residents’ concerns. To help the staff further understand the issues and risks involved at Potomac Airfield and the other airports in the county, the Planning Department hired a team of aviation consultants to examine safety and land use compatibility issues around each airport, to research what is being done in other jurisdictions, and to recommend state of the art approaches to address issues in Prince George’s County. For increased public accessibility, this consultant’s report is on the Planning Department website. A printed copy of the consultant’s report is available as a reference at the following public libraries: • Hyattsville Branch Library, 6532 Adelphi Road, Hyattsville • Bowie Branch Library, 15210 Annapolis Road, Bowie • Surratts-Clinton Branch Library, 9400 Piscataway Road, Clinton Airport Land Use Compatibility and Air Safety Study An aviation consultant, William V. Cheek and Associates of Prescott, Arizona, conducted research and field study around the county’s four general aviation airports during the past summer. They prepared a detailed report, entitled the Airport Land Use Compatibility and Air Safety Study for the Maryland National Capital Park and Planning Commission, which was submitted to the Planning Department on November 10, 2000. -

200115 SFRA Course

Security-related procedures and requirements are a fact of life for today's pilots, especially those who operate in the Washington, DC metropolitan area Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA) and the DC Flight Restricted Zone (FRZ). Although the rules may sound intimidating, they are not difficult. This course is intended to provide the information you need to fly safely, correctly, and confidently in this airspace. 1 This slide provides a summary of the changes made since the last version of this course. The only changes for this edition are new procedures for filing flight plans for the Flight Restricted Zone, or FRZ. As stated in the regulatory review section, 14 CFR 91.161 requires this training for pilots flying under visual flight rules (VFR) within a 60 nm radius of the Washington DC VOR/DME. This training is a one-time-only requirement, but it is a good idea to periodically review the material for updates and to refresh your knowledge. You should print the certificate of training completion. You do not have to carry it with you, but you must provide it within a reasonable period of time if requested. Now, let’s get started. 2 After the September 11 terrorist attacks, security authorities established the Washington DC Air Defense Identification Zone – the ADIZ – and the Flight Restricted Zone – the FRZ – to protect the nation’s capital. The ADIZ and the FRZ were established and operated via temporary flight restriction, or TFR, until the FAA developed a final rule that took effect on February 17, 2009. That rule codified the ADIZ and the FRZ in 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) part 93 as the DC Special Flight Rules Area (SFRA). -

COUNTY COUNCIL of PRINCE GEORGE's COUNTY, MARYLAND SITTING AS the DISTRICT COUNCIL 2002 Legislative Session Bill No

COUNTY COUNCIL OF PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND SITTING AS THE DISTRICT COUNCIL 2002 Legislative Session Bill No. CB-51-2002 Chapter No. 46 Proposed and Presented by The Chairman (by request – Planning Board) Introduced by Council Members Shapiro, Hendershot, and Scott Co-Sponsors Date of Introduction May 21, 2002 ZONING BILL AN ORDINANCE concerning General Aviation Airports and Aviation Policy Areas For the purpose of defining and adopting land use regulations for Aviation Policy Areas, providing for designation of Aviation Policy Areas adjacent to public use, general aviation airports, establishing procedures for amendment of the Aviation Policy Area regulations for individual properties, and making related amendments to the Zoning Ordinance. BY repealing and reenacting with amendments: Sections 27-107.01(a), 27-229(b), and 27-333, The Zoning Ordinance of Prince George's County, Maryland, being also SUBTITLE 27. ZONING. The Prince George's County Code (1999 Edition, 2001 Supplement). BY adding: Sections 27-548.32, 27-548.33, 27-548.34, 27-548.35, 27-548.36, 27-548.37, 27-548.38, 27-548.39, 27-548.40, 27-548.41, 27-548.42, 27-548.43, 27-548.44, 27-548.45, 27-548.46, 27-548.47, 27-548.48, and 27-548.49, The Zoning Ordinance of Prince George's County, Maryland, being also CB-51-2002 (DR-2) – Summary Page 2 SUBTITLE 27. ZONING The Prince George's County Code (1999 Edition, 2001 Supplement). SECTION 1. BE IT ENACTED by the County Council of Prince George's County, Maryland, sitting as the District Council for that part of the Maryland-Washington Regional District in Prince George's County, Maryland, that the following findings are made: A. -

College Park Airport Plan and Presentation

College Park Airport Safety Project Report Presenter: Christine Fanning Chief of Natural and Historical Resources Division M-NCPPC, Department of Parks and Recreation Prince George’s County Safety Project: Goals • Safety for Public and Pilots • Environmental Stewardship - Minimize Impact & Restore Resources • Enhanced Amenities • Improved Community Engagement and Communications Safety Project: Phases • Phase One: Airport Layout Plan Development includes Obstruction Analysis (2012) • Phase Two: Runway Renovation and Compliance with FAA / MAA Threshold Recommendations (2019) • Phase Three: Obstruction Removal and Conservation / Community Commitment (2020) • Phase Four: Precision Guidance System and Taxiway Renovation (2021) Safety Project: Compliance Met or exceeded all Federal, State, County and Local Regulations • Federal Aviation Administration (Federal) • Army Corp of Engineers (Federal) • Maryland Department of the Environment (State) • Department of Natural Resources (State) • Maryland Aviation Administration (State) • Prince George's County Soil Conservation District (County) • Prince George's County Tree Conservation Plan (County) • City of College Park tree canopy replacement requirements Airport Operations • Airport operating license was renewed on October 1, 2020 through September 30, 2021 by the Maryland Aviation Administration • Airplane traffic over the past three years: - 2018: 5 flights/day, 36 flights/week, 155 flights/month - 2019: 8 flights/day, 58 flights/week, 252 flights/month - 2020: 6 flights/day, 41 flights/week, -

College Park Airport (CGS) Maryland Economic Impact of Airports for More Information, Please Contact

Maryland Benefits from Airports - Maryland’s economic well-being is interconnected with its vibrant airport system and its robust aviation industry. The State’s aviation system allows the community at-large to capitalize on an increasingly global marketplace. - Aviation in Maryland both sustains and leads economic growth and development. Protecting and investing in airports will support the aviation industry and sustain the industry’s positive impact on local, regional, and state economies. With continued support, Maryland’s dynamic aviation system will continue to provide a significant economic return in the years to come. - When the regional and local economic impacts of Maryland’s 34 public-use general aviation and scheduled commercial service airports (excluding Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport) are added together, over 9,900 jobs can be traced to the aviation industry. These employees receive more than $583 million in total payroll, and generate nearly $1.1 billion in total economic activity – over $867 million in business revenue and $272 million in local purchases. - The total employment numbers for Maryland’s public-use general aviation and scheduled commercial service airports includes nearly 5,000 direct jobs created by airport and visitor activity at these airports. Over 2,300 jobs were supported in local economic sectors as a result of purchases for goods and services by those 5,000 directly-employed workers; and, over 2,600 indirect jobs were supported by over $272 million of local purchases by airport tenants. - Nearly $583 million dollars in personal wages and salary income was created in the State of Maryland by the activity at these 34 airports. -

College Park Airport Authority

College Park Airport Authority Minutes of Meeting (Virtual) 1 April 2021 The virtual meeting was called to order by the Chair, Jack Robson at 7:05 PM. Members present were David Dorsch, Chris Dullnig, Gabriel Iriarte, David Kolesar, and Anna Sandberg. James Garvin was absent. Also in attendance were Lee Sommer, Airport Manager, and Stephen Edgin, Assistant Manager. The Purple Line work on Paint Branch Creek to the north of the airport has about a month to go. They will remove the temporary access road that they installed across the north end of the airport. The tree trimming portion of the M-NCPPC runway safety project should complete on April 2nd or so. However, plantings and tree replacement will continue into the indefinite future. M-NCPPC has been meeting with the disc golf group, but the group has been unable to reach a consensus on tree placement. The replacement of the runway lights with LED fixtures should begin in July. In addition, installation of the Precision Approach Path Indicator (PAPI) systems, along with an electrical upgrade should also start in the same time frame. The power and PAPI systems are permit dependent so the actual dates are uncertain. The State will be providing a cost-sharing grant for this safety improvement. The response to a memo sent to the Mayor and Council by Mr. Gray, a Yarrow resident, was discussed at length. The Authority members unanimously approved the response and a copy is attached to the Minutes. Mr. Sommer reported that: There are 39 currently based aircraft There were 99 Transient operations There were 359 Tenant operations He also advised that when the restricted use of the Operations Building was to occur was still unknown. -

D.C. Renaissance

[ABCDE] Volume 3, Issue 7 D.C. Renaissance INSIDE Art Deco Radio — All the 13 Drive 17 Rage Headlines on Amending the 18 Trial 20 Constitution April 27, 2004 © 2004 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY Volume 3, Issue 7 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program D.C. Renaissance In the Field KidsPost Article: “The Unboring Illustrated True Story of the ➤ http://www.soulofamerica.com/ Washington Area from 1600 to Right Now, Part 7” cityfldr2/wash15.html U Street/Shaw District Lesson: The 1920s and 1930s the Chrysler Building. More than 20 years before the Harlem were decades of development, U Street and Howard University Renaissance, the D.C. Renaissance was daring and dangers, and the D.C. were the center of a thriving taking place on U Street. Jazz singer Renaissance during which writers, African American community. Pearl Bailey gave U Street the nickname musicians and artists were a Musicians, artists and writers “the Black Broadway.” Visit history and significant part of D.C. life. joined the doctors and attorneys, see today’s renaissance taking place in Level: All beauticians and barbers, Duke Ellington’s old neighborhood. newspapers and bank of Shaw. Subjects: History, social studies, Before the Harlem Renaissance ➤ http://americanhistory.si.edu/ art, music was the D.C. Renaissance of Duke youmus/ex11fact.htm Field to Factory, National Museum of Related Activity: Language arts, Ellington, The Washingtonians, American History geography, technology Jean Toomer and Sterling Brown. If you couldn’t be there, radio Explores the movement of thousands About This Series: brought jazz, blues and new voices from the rural South to the new This is the seventh of nine parts into the American home. -

Appendix 2 College Park Runway and Taxiway Rehabilitaion Letter

October 1, 2018 Mr. Eric J. DeDominicis, P.E. Deputy Practice Leader, Aviation Urban Engineers, Inc. 1 South Street, Suite 1275 Baltimore, MD 21202 Ref: RDM Job No. 1751: Runway and Taxiway Rehabilitation at College Park Airport, College Park, Maryland. Dear Mr. DeDominicis: RDM International Inc. (RDM) was retained by Urban Engineers, Inc. (Urban) to perform functional evaluations for the Runway 15-33, parallel taxiway, and associated connectors at College Park Airport (CGS) College Park, MD. The primary objective of the project is to evaluate the functional condition and assist Urban with developing design alternatives for pavement rehabilitation. Runway 15-33 is 2,607 feet long by 60 feet wide and is asphalt concrete (AC) surfaced. However, both runway ends are displaced and the total pavement length is approximately 2,983 feet long. The project limits identified for the runway and taxiways are shown in Appendix A. RDM’s scope of this project consisted of a pavement condition survey and functional evaluation considerations. Nondestructive testing or other forms of physical testing for the structural analysis pavements were not performed. All repair / rehabilitation recommendations are based on visual inspection of pavements. Following procedures detailed in FAA Advisory Circular 150/5380-7B, “Airport Pavement Management Program” and ASTM D 5340, “Standard Test Method for Airport Pavement Condition Index Surveys” , RDM performed a pavement condition survey for the runway and taxiway pavements within the project limits. The survey consisted of a visual inspection to identify pavement distresses at the surface resulting from the influence of aircraft traffic loading, environment weathering or erosion, and other factors relating to potential construction material deficiencies. -

Space Hudson River and East River Exclusion Special

§ 93.343 14 CFR Ch. I (1–1–11 Edition) VHF frequency 121.5 or UHF frequency Traffic Control-assigned course and re- 243.0. main clear of the DC FRZ. (d) Before departing from an airport (c) If using VFR egress procedures, a within the DC FRZ, or before entering pilot must— the DC FRZ, all aircraft, except DOD, (1) Depart as instructed by Air Traf- law enforcement, and lifeguard or air fic Control and expect a heading di- ambulance aircraft operating under an rectly out of the DC FRZ until the FAA/TSA airspace authorization must pilot establishes two-way radio com- file and activate an IFR or a DC FRZ munication with Potomac Approach; or a DC SFRA flight plan and transmit and a discrete transponder code assigned by (2) Operate as assigned by Air Traffic an Air Traffic Control facility. Aircraft Control until clear of the DC FRZ, the must transmit the discrete transponder DC SFRA, and the Class B or Class D code at all times while in the DC FRZ airspace area. or DC SFRA. (d) If using VFR ingress procedures, the aircraft must remain outside the § 93.343 Requirements for aircraft op- erations to or from College Park DC SFRA until the pilot establishes Airport, Potomac Airfield, or Wash- communications with Air Traffic Con- ington Executive/Hyde Field Air- trol and receives authorization for the port. aircraft to enter the DC SFRA. (a) A pilot may not operate an air- (e) VFR arrivals: craft to or from College Park Airport, (1) If landing at College Park Airport MD, Potomac Airfield, MD, or Wash- a pilot may receive routing via the vi- ington Executive/Hyde Field Airport, cinity of Freeway Airport; or MD unless— (2) If landing at Washington Execu- (1) The aircraft and its crew and pas- tive/Hyde Field or Potomac Airport, sengers comply with security rules the pilot may receive routing via the issued by the TSA in 49 CFR part 1562, vicinity of Maryland Airport or the subpart A; Nottingham VORTAC. -

The Future of Tipton Airport in Anne Arundel County

The Future of Tipton Airport in Anne Arundel County by Pranita Ranbhise Under the supervision of Professor Melina Duggal Course 788: Independent Study The University of Maryland- College Park Fall 2016 PALS - Partnership for Action Learning in Sustainability An initiative of the National Center for Smart Growth Gerrit Knaap, NCSG Executive Director Uri Avin, PALS Director, Kim Fisher, PALS Manager 1 Executive Summary Tipton Airport is located in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. It is a General (GA) airport, classified as a reliever airport by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). It is the reliever airport to the Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport (BWI), which is located less than 13 miles from Tipton. The airport plans to extend their runway from 3,000 feet to 4,200 feet. The main objective for this expansion is to increase the number of larger turbo-planes and business aircrafts, which require longer runways that can use the facility. This will expand the airport’s market reach and user base, allowing it to improve the ease of flying for potential users. The purpose of this study is to determine the future demand for corporate service and other air traffic at the airport in light of the runway expansion, and to recommend additional variables that will help increase air traffic. The report provides a detailed description of Tipton Airport, including its location and context, airport services, and a comparison of these services with similar airports in Maryland. It also includes an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for the airport, based on a review of FAA records and recommendations, market analysis, general aviation airport demand drivers, the Maryland Aviation Administration (MAA) reports, and information from airport experts. -

College Park Aviation Museum & College Park Airport

College Park Aviation Museum & College Park Airport Where Your Event Takes Off Rental Rules and Regulations The College Park Airport is the world’s oldest continuously operating airport and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. When planning your event, please remember that the preservation of the historic artifacts is the first consideration during all events. Planning events at this location may differ from other rental venues due to the need to preserve its’ historic integrity. Our knowledgeable staff will guide you through the process to ensure a successful and memorable event! 1909 & 1985 Cpl. Frank Scott Drive, College Park, Maryland 20740 301-864-6029 TEL / 301-927-6472 FAX /301-445-4512 TTY [email protected] www.collegeparkaviationmuseum.com / www.pgparks.com 1 Table of Contents VENUE RULES AND REGULATIONS ............................................................................................................. 4 Contact Information ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Directions ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 TO RENT A VENUE ................................................................................................................................. 6 RESERVATIONS .............................................................................................................................................