Maradana: Reading Shared Public Space Shared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka November 2017 Dimantha De Silva, Ph.D(Calgary), P.Eng.(Alberta) Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa 1 SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Table of Content Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................. 4 Study Area .................................................................................................................................... 5 Existing Transport Master Plans .................................................................................................. 6 Indicator 1: Extent to which Transport Plans Cover Public Transport, Intermodal Facilities and Infrastructure for Active Modes ............................................................................................... 7 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 8 Indicator 2: Modal Share of Active and Public Transport in Commuting................................. 13 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

Battle of the “Species” to Play the Role of “National Bourgeoisie”: a Reading of Shyam Selvadurai's Cinnamon Gardens A

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH9-XO\,661 Battle of the “Species” to play the Role of “National bourgeoisie”: A Reading of Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy Niku Chetia Gauhati University India Decolonization is quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men. (Fanon, 1963) Fanon had quite rightly pointed out in his work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that during the colonial and post-colonial period, the battle for dominating, suppressing and subjugating certain groups of people by a superior class never ceases to exist. He explains that there are two species- “Colonisers” and “National bourgeoisie” of the colonised- who seeks to rule the country after independence. Though he places his ideas in an African context, his arguments seems valid even for a South-East Asian country like Sri Lanka. After colonisers left the nation, there emerged a pertinent question - Who would play the role of national bourgeoisie? The struggle to play the coveted role drives Sri Lanka through ethnic conflicts and prejudices among them. The two dominant “species” battling for the position are: Tamils and Sinhalese. Considering the Marxist model of society, Althusser in work On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses claims that the social structure is composed of Base and Superstructure. The productive forces (labour forces/working class) and relations of production forms the Base while religious ideology, ethics, politics, family, identity and politico-legal (law and state) forms the superstructure (237). The National bourgeoisie exists in the superstructure. Both the groups try to survive in the superstructure.The objective of this paper is to study Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy and excavate the diverse ways in which these two mammoth ethnic groups struggle to oust one another and form the “national bourgeoisie”. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

T H3586 Possibilities of Reducing Train Delays

/,©/ VOW ( Cfr/ f SLO/g POSSIBILITIES OF REDUCING TRAIN DELAYS BETWEEN COLOMBO FORT AND MARADANA LIBRARY (jur/ERSSTY OF MORATUWA, SFJ LAHKA mor*tuwa Vithanage Chinthaka Dasun Jayasekara (138327B) Degree of Master of Science Department of Civil Engineering V-/ 3 5 86 4 University of Moratuwa £ V Qor-3 Sri Lanka May 2017 University of Murtiluwn Jf » 6^4 \~r TH3586 S5 G T H3586 POSSIBILITIES OF REDUCING TRAIN DELAYS BETWEEN COLOMBO FORT AND MARADANA Vithanage Chinthaka Dasun Jayasekara (138327B) Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Transportation Department of Civil Engineering University of Moratuwa Sri Lanka May 2017 DECLARATION OF THE CANDIDATE AND SUPERVISOR “I declare that this is my own work and this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any other University or Institute of higher learning and to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not any material previously published or written by another person except where the acknowledgement is made in the text. Also, I hereby grant to University of Moratuwa the non-exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my thesis, in whole or in part in print, electronic or other medium. I retain the right to use this content in whole or parts in future works (such as articles or books) 20 \ ^ Signature: Date: o & The above candidate has carried out research for the Masters Dissertation under my supervision. c?o e>xoir Signature of the supervisor: Date: 1 ABSTRACT Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) is operating around 300 passenger train movements daily across its 1400 Km rail network. -

Introduction to Light Rail Transit Project Colombo– Sri Lanka

Light Rail Transit Project – JICA Ministry of Megapolis and Western Development INTRODUCTION TO LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT PROJECT COLOMBO– SRI LANKA 1 CONTENT LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT FOR COLOMBO IN A NUT SHELL PROPOSED LRT NETWORK FIANCING FOR THE LRT PROJECT LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT PROJECT FINANCED BY JICA ISSUES, CONSTRAINTS AND CHALLENGES Social Environmental Technical Legal Light Rail Transit Project – JICA Ministry of Megapolis and Western 2 1 Development LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT FOR COLOMBO CURRENT STATUS OF MEGAPOLIS TRANSPORT INTRODUCTION OF COLOMBO MASTER PLAN LRT • 10 Million Passenger Daily Trips within CMR • • One of the key public transport • 1.9 million Daily Passengers The Western Region Megapolis improvements identified in the Entering the CMC limits each Day. Transport Master Plan was Megapolis Transport Master is the • Average Travel Speed in CMR developed encompassing all aspects introduction of a LRT system as a 17km/h of transportation to provide a new mode of public transport in the • Average Travel Speed within CMC framework for urban transport CBD and extended to the out of CBD 12km/h development in Western Region up of the Western Region • With Population Increase the to 2035 while giving high priority to Need of Travel is going to Increase improve public transportation in the Western Region Light Rail Transit Project – JICA Ministry of Megapolis and Western 3 2 Development PROPOSED LRT NETWORK Kelaniya Elevated RTS – Line 1 (Green) Fort –Kollupitiya-Bambalapitiya- Borella-Union Place- Maradana (15km) Fort MMH Elevated RTS -

Partnership to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport – Case Study of Colombo, Sri Lanka

DFID Assisted, Institute of Development Engineering, WEDC Executed Research Project Partnership to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport – Case Study of Colombo, Sri Lanka Sri Lanka Country Report April 2002 The Research Project was funded by DFID, UK Government through Institute of Development Engineering – WEDC, Loughborough University, United Kingdom Partnership to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport – Case Study Colombo, Sri Lanka Sri Lanka Country Report April 2002 SEVANATHA – Urban Resource Center 14, School Lane, Nawala, Rajagiriya Sri Lanka Winner of IYSH Memorial Prize - 2001 Tel/Fax: 94-01-878893 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements The Research Team of SEVANATHA organization would like to extend its sincere gratitudes to the following persons who have assisted the project activities in numerous ways. Without their support and contributions it would not have been possible to produce this research report. They included; • Dr. M. Sohail Khan, Research Manager, Institute of Development Engineering / WEDC Civil and Building Engineering Department, Loughborough University, UK. • The members of the Research Advisory Committee. • The President of Private Bus Owners Association of Sri Lanka. • Secretary General, Passenger Association of Sri Lanka. • The community leaders of six urban poor settlements where case studies were carried out. • The members of households of the six urban poor settlements who have provided information for the research study. • The officials of the concerned government institutions and local authorities. • The staff of SEVANATHA organization including the President of SEVANATHA, Programme Managers, Field Staff and the Office Secretary. H.M.U. Chularathna Coordinator SEVANATHA Research Team Contents 1.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………..………. 1 1.1 Project Details …………………………………………………………………. -

Railway Efficiency Improvement Project: Social Due Diligence Report

Social Due Diligence Report November 2018 Sri Lanka: Railway Efficiency Improvement Project Construction of Passenger Facilities at Colombo Fort and Maradana Railway Stations Prepared by the Project Management Unit, Colombo Suburban Railway Project, and Ministry of Transport & Civil Aviation for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 14 October 2018) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee/s (SLRe/SLRs) SLRe1.00 = $0.005891 $1.00 = SLRs169.74 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank FCSRP – Colombo Suburban Railway Project GRC – grievance redress committee MOTCA – Ministry of Transport & Civil Aviation PMU – project management unit SLR – Sri Lanka Railways TA – technical assistance This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Objectives and Methodology ........................................................................................... 2 III. Summary of Document Verification and Field Observations ........................................... -

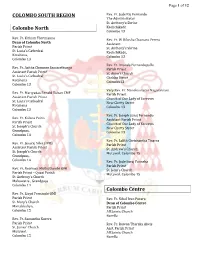

OCR Document

Page 1 of 12 COLOMBO SOUTH REGION Rev. Fr. Jude Raj Fernando The Administrator St. Anthony's Shrine Colombo North Kochchikade Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Kithsiri Thirimanne Rev. Fr. W Dilusha Chamara Perera Dean of Colombo North Assistant Parish Priest St. Anthony's Shrine St. Lucia's Cathedral Kochchikade, Kotahena, Colombo 13 Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Ananda Fernandopulle Rev. Fr. Asitha Chamara Samarathunga Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest St. Anne's Church St. Lucia's Cathedral Chekku Street Kotahena Colombo13 Colombo 13 Very Rev. Fr. Manokumaran Nagaratnam Rev. Fr. Mariyadas Renald Ruban CMF Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest Church of Our Lady of Sorrows St. Lucia's Cathedral New Chetty Street Kotahena Colombo 13 Colombo 13 Rev. Fr. Joseph Suraj Fernando Rev. Fr. Kalana Peiris Assistant Parish Priest Parish Priest Church of Our Lady of Sorrows St. Joseph's Church New Chetty Street Grandpass, Colombo 13 Colombo 14 Rev. Fr. Lalith Chrishantha Tissera Rev. Fr. Jesuraj Silva (IVD) Parish Priest Assistant Parish Priest St. Andrew's Church St. Joseph's Church Mutuwal, Colombo 15 Grandpass, Colombo 14 Rev. Fr. Jude Suraj Fonseka Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Newman Muthuthambi OMI St. John's Church Parish Priest – Quasi Parish Mutuwal, Colombo 15 St. Anthony’s Church Mahawatte , Grandpass Colombo 14 Colombo Centre Rev. Fr. Lloyd Fernando OMI Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Nihal Ivan Perera St. Mary's Church Dean of Colombo Centre Mattakkuliya, Parish Priest Colombo 15 All Saints Church Borella Rev. Fr. Samantha Kurera Parish Priest Rev. Fr. Ruwan Tharaka Alwis St. James' Church Asst. Parish Priest Mutuwal, All Saints Church Colombo 15 Borella Page 2 of 12 Rev. -

Challenges and Opportunities When Installing Hv Cable in Australia and Sri Lanka

ReturnClose and to SessionReturn CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES WHEN INSTALLING HV CABLE IN AUSTRALIA AND SRI LANKA Naveed RAHMAN, Olex Australia (a Nexans Company), (Australia), [email protected] Ken BARBER, Olex Australia (a Nexans Company), (Australia), [email protected] ABSTRACT and construction and all three contracts were awarded to Olex Australia Pty Ltd. The objective of this project was to Those involved in the cable installation field know only full extend the 110 kV power supply system and optical fibre well, every installation project has unique challenges, with communication system in the Brisbane area, by constructing no two installations being exactly the same. Having just two 110kV cable circuits and Optical Fibre communication completed two significant 132kV cable contracts in two links between the existing Charlotte Street Substation and completely different cities, we believe there are however, the new Carindale Termination Point via Wellington Road some valuable lessons learnt for future projects. Substation. This paper looks at the design and construction of two Being two large EHV underground cable installation projects projects, one in the city of Colombo, Sri Lanka and the other of similar size one in South East Asia and the other in in the city of Brisbane, Australia. Both are the most Australia there are similarities as well as differences both in significant cable projects for each country and in both cases design and construction aspects of each project. The the objective was to extend the 132kV power supply system Greater Colombo Grid substation project was to be and optical fibre communication system together with the constructed in a densely populated South East Asian city construction of new substations.