Economic and Financial Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sri Lanka Railways

SRI LANKA RAILWAYS PROCUREMENT NOTICE 3,850 CUBES OF TRACK BALLAST TO LOWER DISTRICT PROCUREMENT NO - SRS/F.7739 01. The Chairman, Department Procurement Committee (Major), Sri Lanka Railways, will receive sealed bids from the suppliers for the supply of Track Ballast to the following places on National Competitive Bidding Basis. These bids will be evaluated and awarded separately for each item mentioned below: Item Delivery period Place Cubes No. (Months) 1. Kalutara South 500 04 2. Train Halt No. 01 1,000 06 3. 20M. 35Ch. - 20M. 40Ch. 500 04 (Between Pinwatte & Wadduwa Railway Stations) 4. Pinwatte (18M. 60Ch) 200 02 5. Panadura (near Railway Bridge) 200 02 6. Moratuwa Railway Yard 200 02 7. Angulana Railway Station, Colombo 200 02 End 8. Ratmalana Railway Station 250 03 9. Nawinna Railway Station (Kelani 300 03 Valley Line) 10. Malapalla (Kelani Valley Line) 200 02 11. Watareka (Kelani Valley Line) 100 01 12. Liyanwala (Kelani Valley Line) 200 02 02. Bids shall be submitted only on the forms obtainable from the Office of the Superintendent of Railway Stores, up to 3.00 p.m. on 23.09.2020 on payment of a non-refundable document fee of Rs.7,000.00 (Rupees Seven Thousand) only. 03. Bids will be closed at 2.00 p.m. on 24.09.2020. 04. The bidders shall furnish a bid security amounting Rs.300,000.00 (Sri Lankan Rupees Three Hundred Thousand) only as part of their bid. 05. Bids will be opened immediately after the closing time at the Office of the Superintendent of Railway Stores. -

Clean Energy and Access Improvement Project

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 39419 July 2008 SRI: Clean Energy and Access Improvement Project Prepared by Ceylon Electricity Board The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD NATIONAL GRID DEVELOPMENT PROJECT LOAN AGREEMENT NO: RESETTLEMENT AND COMPENSATION PLAN ENVIRONMENT UNIT CEYLON ELECTRICITY BOARD COLOMBO SRI LANAKA Abbreviations ADB - Asian Development Bank BoI - Board of Investment 0C - Celsius CEA - Central Environmental Authority CEB - Ceylon Electricity Board db(A) - A-Weighted sound measurement in decibels DS - Divisional Secretary EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EPL - Environmental Protection License GIS - Gas Insulated Substation GN - Grama Niladhari GS - Grid Substation IEC - International Electrotechnical Commission IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IPP - Independent Power Producer km - kilometer kV - kilovolt LoI - Letter of Intent m - meter mm - millimeter MOH - Medical Officer of Health MVA - Megavolt Ampere MW - Megawatt NCRE - Non-Conventional Renewable Energy NGO - Non Government Organization NIRR - National Policy on Involuntary Resettlement NEA - National Environment Act PAA - Project Approving Agency PAC - Project Approving Committee PSS/e - Power System Simulation REA - Rapid Environmental Assessment ROW - Right of Way SEA - Sustainable Energy Authority SLBC - Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation SPPA - Small Power Purchase Agreement SPP - Small Power Producer VRR - Victoria, Randenigala, Rantembe W - Watt Page 1 Executive Summary This Resettlement and Compensation Plan covers the proposed National Grid Development Project of Ceylon Electricity Board, Sri Lanka, scheduled for implementation from year 2008. -

CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs CoMTrans UrbanTransport Master Plan Final Report CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1.1 Definition The Western Province is the most developed province in Sri Lanka and is where the administrative functions and economic activities are concentrated. At the same time, forestry and agricultural lands still remain, mainly in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the province. And also, there are some local urban centres which are less dependent on Colombo. These areas have less relation with the centre of Colombo. The Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined in order to analyse and assess future transport demands and formulate a master plan. For this purpose, Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined by: A) areas that are already urbanised and those to be urbanised by 2035, and B) areas that are dependent on Colombo. In an urbanised area, urban activities, which are mainly commercial and business activities, are active and it is assumed that demand for transport is high. People living in areas dependent on Colombo area assumed to travel to Colombo by some transport measures. 4.1.2 Factors to Consider for Future Urban Structures In order to identify the CMA, the following factors are considered. These factors will also define the urban structure, which is described in Section 4.3. An effective transport network will be proposed based on the urban structure as well as the traffic demand. At the same time, the new transport network proposed will affect the urban structure and lead to urban development. -

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka

SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Sustainable Urban Transport Index Colombo, Sri Lanka November 2017 Dimantha De Silva, Ph.D(Calgary), P.Eng.(Alberta) Senior Lecturer, University of Moratuwa 1 SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT INDEX Table of Content Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background and Purpose .............................................................................................................. 4 Study Area .................................................................................................................................... 5 Existing Transport Master Plans .................................................................................................. 6 Indicator 1: Extent to which Transport Plans Cover Public Transport, Intermodal Facilities and Infrastructure for Active Modes ............................................................................................... 7 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 8 Indicator 2: Modal Share of Active and Public Transport in Commuting................................. 13 Summary ................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

39296 Sri-Lanka.Book

Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport A Case Report: Colombo, Sri Lanka SEVANATHA Urban Resources Centre Edited by M. Sohail Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University 2003 Water, Engineering and Development Centre Loughborough University Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK © WEDC, Loughborough University, 2003 Any part of this publication, including the illustrations (except items taken from other publications where the authors do not hold copyright) may be copied, reproduced or adapted to meet local needs, without permission from the author/s or publisher, provided the parts reproduced are distributed free, or at cost and not for commercial ends, and the source is fully acknowledged as given below. Please send copies of any materials in which text or illustrations have been used to WEDC Publications at the address given above. SEVANATHA Urban Resources Centre (2003) Partnerships to Improve Access and Quality of Public Transport - A Case Report: Colombo, Sri Lanka Series Editor: M. Sohail A reference copy of this publication is also available online at: http://www.lboro.ac.uk/wedc/publications/piaqpt-srilanka ISBN Paperback 1 84380 036 5 This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of low-income countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Designed and produced at WEDC by Glenda McMahon, Sue Plummer and Rod Shaw Acknowledgements The Sevanatha Research Team would like to extend their sincere gratitude to the following persons, who have assisted the project activities in numerous ways. -

Battle of the “Species” to Play the Role of “National Bourgeoisie”: a Reading of Shyam Selvadurai's Cinnamon Gardens A

9ROXPH,,,,VVXH9-XO\,661 Battle of the “Species” to play the Role of “National bourgeoisie”: A Reading of Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy Niku Chetia Gauhati University India Decolonization is quite simply the replacing of a certain “species” of men by another “species” of men. (Fanon, 1963) Fanon had quite rightly pointed out in his work, The Wretched of the Earth (1961) that during the colonial and post-colonial period, the battle for dominating, suppressing and subjugating certain groups of people by a superior class never ceases to exist. He explains that there are two species- “Colonisers” and “National bourgeoisie” of the colonised- who seeks to rule the country after independence. Though he places his ideas in an African context, his arguments seems valid even for a South-East Asian country like Sri Lanka. After colonisers left the nation, there emerged a pertinent question - Who would play the role of national bourgeoisie? The struggle to play the coveted role drives Sri Lanka through ethnic conflicts and prejudices among them. The two dominant “species” battling for the position are: Tamils and Sinhalese. Considering the Marxist model of society, Althusser in work On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses claims that the social structure is composed of Base and Superstructure. The productive forces (labour forces/working class) and relations of production forms the Base while religious ideology, ethics, politics, family, identity and politico-legal (law and state) forms the superstructure (237). The National bourgeoisie exists in the superstructure. Both the groups try to survive in the superstructure.The objective of this paper is to study Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens and Funny Boy and excavate the diverse ways in which these two mammoth ethnic groups struggle to oust one another and form the “national bourgeoisie”. -

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka

Census Codes of Administrative Units Western Province Sri Lanka Province District DS Division GN Division Name Code Name Code Name Code Name No. Code Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Sammanthranapura 005 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mattakkuliya 010 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Modara 015 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Madampitiya 020 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Mahawatta 025 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthmawatha 030 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Lunupokuna 035 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Bloemendhal 040 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena East 045 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kotahena West 050 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade North 055 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Jinthupitiya 060 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Masangasweediya 065 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 New Bazaar 070 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass South 075 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Grandpass North 080 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Nawagampura 085 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Maligawatta East 090 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Khettarama 095 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade East 100 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Aluthkade West 105 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Kochchikade South 110 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Pettah 115 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Fort 120 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Galle Face 125 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Slave Island 130 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Hunupitiya 135 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Suduwella 140 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo 03 Keselwatta 145 Western 1 Colombo 1 Colombo -

Ongoing Project Details

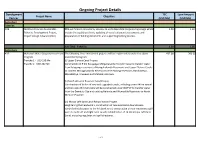

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

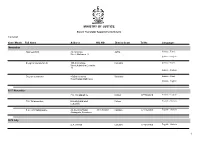

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Fuel Economy of Light Duty Vehicles in Sri Lanka the Baseline

FUEL ECONOMY OF LIGHT DUTY VEHICLES IN SRI LANKA THE BASELINE Prepared by Thusitha Sugathapala Clean Air Sri Lanka August 2015 Fuel Economy of Light Duty Vehicles in Sri Lanka –The Baseline ACRONYMS ACEA European Automobile Manufacturers Association AirMAC Air Resource Management Centre CA2AP Clean Air 2000 - An Action Plan CAA Clean Air Asia CAASL Civil Aviation Authority of Sri Lanka CAI-Asia Clean Air Initiative for Asian Cities CBSL Central Bank of Sri Lanka CEA Central Environmental Authority CEB Ceylon Electricity Board CEYPETCO Ceylon Petroleum Corporation CI Compression ignition CISIR Ceylon Institute for Scientific and Industrial Research Clean Air SL Clean Air Sri Lanka CPSTL Ceylon Petroleum Terminals Ltd CSE Centre for Science and Environment CUTP Colombo Urban Transport Project DMT Department of Motor Traffic E3ST Energy Efficient and Environmentally Sustainable Transport EECA Energy Efficiency and Conservation Authority, New Zealand EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EPL Environmental Protection Licence EU European Union EV Electric vehicles FCV Fuel cell vehicle GHG Greenhouse gas GTZ German Development Cooperation HEV Hybrid-electric vehicle HOV High occupancy vehicle IC Internal combustion ICCT International Council on Clean Transportation IEA International Energy Agency IIASA International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis Clean Air Sri Lanka i Fuel Economy of Light Duty Vehicles in Sri Lanka –The Baseline IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change kgOE kg of Oil Equivalent LCA Life cycle analyse LDV Light-duty -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind.