Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Neuromuscular Exercise and Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonttihakuohjelmointi 2021-2025

TONTTIHAKUOHJELMOINTI 2021-2025 Yhtiömuotoiset tontit Virpi Ekholm, kiinteistöjohtaja 15.4.2021 • Tehdään viisivuotiskaudeksi • Perustuu asemakaavoitusohjelmaan • Ohjelmoinnissa esitetään kunakin vuonna yleiseen tonttihakuun ja erilaisiin kilpailuihin haettavaksi tuleva rakennusoikeuden määrä • Ohjelmoinnissa esitetään vuosittain kohtuuhintaiseen asuntotuotantoon haettavaksi laitettavan rakennusoikeuden osuus • Kohtuuhintaisen tuotannon määritelmä MAL4-sopimuksesta: a) ARA-rahoituksella toteutettavat • Tavalliset vuokra-asunnot (pitkä ja lyhyt korkot) • Asumisoikeusasunnot • Erityisryhmäasunnot vanhusväestölle, asunnottomille, kehitysvammaisille, opiskelijoille ja nuorisolle sekä muille erityisryhmille (pitkä korkotuki + investointiavustus) • ARA:n tukemat monimuotoisen asumisen kokeilut, kuten sekarahoitteiset kohteet asuntojen monipuolisen hallintamuodon varmistamiseksi b) kuntakonsernin oma ARA-vuokratasoa vastaava vuokra-asuntotuotanto (omakustannusperiaate) 2 • Kohtuuhintaisen vuokra-asuntotuotannon riittävyyden varmistamiseksi tontteja voidaan luovuttaa neuvottelumenettelyllä kaupunkikonserniin kuuluvien vuokra-asuntoyhteisöjen omaan vuokra- asuntotuotantoon • Toteutetaan Hiilineutraali Tampere 2030 tiekartan toimenpiteitä ja tavoitteita, kohdat: 112. Hiilijalanjälkiarviointi (pilotointi) 115. Nollaenergiarakentaminen 117. Kestävän ja älykkään rakentamisen teemat 130. Puurakentaminen 158. Hajautettujen energiajärjestelmien pilotointi. • Yksityisten maanomistajien ja/tai hankekehityskaavojen kautta hakuun tuleva rakennusoikeuden määrä -

Pirkanmaan Maakunnallisesti Arvokkaat Rakennetut

Pirkanmaan maakunnallisesti arvokkaat rakennetut kulttuuriympäristöt 2016 TEEMME MUUTOSTA YHDESSÄ 4.1.2016 Pirkanmaan liitto 2016 ISBN 978-951-590-313-6 Taitto Eila Uimonen, Lili Scarpellini Kannen kuvat: Suolahden kirkon rappu, Punkalaitumen Sarkkilan koulu, Lielahden tehdas, Jäähdyspohjan mylly, Kangasalan seurakuntatalo, Ylöjärven Ylisen asuinkerrostalo. 2013-2016 Lasse Majuri Sisällys Tausta . 4 Tavoitteet. 5 Hankeryhmä. .5 Tarkastelualue ja kohdejoukko. .5 Selvitystilanne . 7 Menetelmät. 7 Tarkasteltavien kohteiden valinta. .7 Pirkanmaan erityispiirteet. .9 Maakunnallisesti arvokkaat kohteet kunnittain . 25 Kohdekortit. .51 Liitteet. .253 Lähteet. 257 3 Tausta Pirkanmaalla on käynnissä uuden kokonaismaakunta- Fyysinen ympäristö muuttuu hitaasti. Pirkanmaan kult- kaavan, Pirkanmaan maakuntakaavan 2040, laatiminen. tuurinen omaleimaisuus saa rakennetusta ympäristöstä Maankäytön eri aihealueet kattava maakuntakaava tulee vahvan perustan. Vaikka arvokkaina pidettyjä ympäristö- korvaamaan Pirkanmaan 1. maakuntakaavan ja voimassa jä ensisijaisesti vaalitaan tuleville sukupolville, on niillä olevat vaihemaakuntakaavat. Maankäyttö- ja rakennusla- merkitystä jokapäiväisen viihtyisän elinympäristön osana. ki edellyttää (28§), että maakuntakaavan sisältöä laadit- Matkailulle ja seudun muille elinkeinoille sekä imagol- taessa on erityistä huomiota kiinnitettävä maisemaan ja le arvokkaista kulttuuriympäristöistä on selkeää hyötyä. kulttuuriperintöön. Pirkanmaan maakunnallisesti arvok- Koska Pirkanmaan maakuntakaava 2040 on luonteeltaan kaita -

7 Ihmisten ELINOLOT JA VIIHTYVYYS

7 IHMISTEN ELINOLOT JA VIIHTYVYYS 7.1 Lähtötiedot ja menetelmät Viher- ja virkistysalueet Näiden lisäksi Rantaväylän läheisyydessä on muu- Nykyisen Rantaväylän ja katuverkoston läheisyys ai- tamia ulkoiluun ja virkistykseen liittyviä kohteita, heuttaa lähialueen asukkaille melu-, päästö- ja viih- Ihmisiin kohdistuvien vaikutusten arvioinnin tavoit- Hankealueella on useita kaupunkipuistoja ja muita joista tärkeimpinä voidaan mainita Santalahden ja tyvyys- ja estevaikutushaittoja sekä turvattomuutta. teena on ollut tunnistaa hankkeen keskeiset vaiku- virkistys- ja viheralueverkoston osia. Tampereen vi- Onkiniemen uimarannat sekä Santalahden, Musta- Rantaväylän vilkas läpikulkuliikenne lisää melua tukset ihmisten elinoloihin ja viihtyvyyteen. Ihmis- heralueohjelma 2005–2014 ja Tampereen kantakau- lahden ja Naistenlahden pienvenesatamat. ja ilmansaasteita. Väylä myös pirstoo ympäristöä ten elinympäristöä koskevia vaikutuksia on käsitelty pungin ympäristö- ja maisemaselvitys 2008 (KYMS) ja vaikeuttaa maankäytön ja yhdyskuntarakenteen myös muissa vaikutusarvioinneissa, esimerkiksi muodostavat viheralueiden pitkän aikavälin tavoite- Asutus ja herkät kohteet kehittämistä. luvut 6 Maankäyttö ja yhdyskuntarakenne, 8 Melu, ja kehittämissuunnitelman, jossa viheralueverkosto 9 Tärinä ja runkomelu, 10 Päästöt ja ilmalaatu sekä on jaettu merkittäviin, toiminnallisesti merkittäviin Rantaväylä kuuluu tiivisti rakennettuun Tampereen 16 Liikenne ja liikenneväylät. ja kehitettäviin osiin sekä toiminnallisiin yhteyksiin. keskusta-alueeseen, ja sen lähivaikutusalueella -

Tampere, Finland

Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland Proposal to hold the 23RD INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES on 21–30 August 2020 in Tampere, Finland CONTENTS Letter of Invitation from the University of Tampere ................................................................................. 3 Letter of Invitation from CISH National Committee (Finnish Historical Society) ................................................. 4 Letter of Invitation from the City of Tampere ........................................................................................ 5 Why Finland – Why Tampere ............................................................................................................. 6 University of Tampere .................................................................................................................... 7 Congress organization ..................................................................................................................... 8 Finances ................................................................................................................................... 10 Finland – your host country............................................................................................................. 11 Tampere – the congress city ........................................................................................................... 12 Travel to the congress site ............................................................................................................ -

Särkänniemen, Mustalahden, Onkiniemen Ja Santalahden

SÄRKÄNNIEMEN, MUSTALAHDEN, ONKINIEMEN JA SANTALAHDEN RANTAPUISTON KEHITTÄMISEN TILANNEKATSAUS JA JATKOTYÖN LINJAUKSET ”Pohjoismaiden vetovoimaisin elämyskaupunki” Kaupunkistrategia 2030 Kaupunginhallituksen kehittämiskokous 16.4.2018 Johtaja Teppo Rantanen / Hankejohtaja Tero Tenhunen 1 12.4.2018 SÄRKÄNNIEMI -MUSTALAHTI –ONKINIEMI –SANTALAHTI KEHITTÄMINEN 1. Pohjoismaiden vetovoimaisin tapahtumakaupunki – strategia ja tavoitteet 2. Särkänniemen alueen kehittämisen tilannekatsaus 3. Onkiniemen kulttuuritehdas 4. Järvikeskus – Lake Center 5. Särkänniemen palloilu- ja monitoimiareena 6. Santalahden rantapuisto 7. Yhteenveto ehdotettavista linjauksista jatkovalmistelua varten 2 12.4.2018 3 12.4.2018 4 12.4.2018 POHJOISMAIDEN VETOVOIMAISIN TAPAHTUMAKAUPUNKI – STRATEGIATAUSTA YLEISTÄ ALUEKOKONAISUUDEN KEHITTÄMISESTÄ Tampereen uuden strategian 2030 ”Sinulle paras” tavoitteena on nostaa Tampere Pohjoismaiden vetovoimaisimmaksi elämyskaupungiksi. Tampereen strategisen kehitysohjelman Viiden Tähden Keskustan merkittävin kaupunkikulttuuria, tapahtumia ja matkailua koskevia tavoitteita toteuttava kokonaisuus on Särkänniemen, Mustalahden, Onkiniemen ja Santalahden rantapuiston alueista koostuva vetovoimainen keskustan järvenrantakaupungin elämyskeidas. Alueen kehittäminen tukee voimakkaasti kasvavaa tapahtumaelinkeinojen toimialaa ja tuo Tampereelle paljon lisää matkailijoita ja työtä. Alueen kehittämisellä on suuri aluetaloudellinen merkitys ja sen kehittäminen kokonaisuutena lisää Tampereen kilpailuetua muihin kasvukeskuksiin. Aluekokonaisuuden -

SILJA TURNAUS 4.-5.8.2018 Kaupin Urheilupuisto

SILJA TURNAUS 4.-5.8.2018 Kaupin Urheilupuisto Otteluohjelmassa muutoksia ikäluokissa F9 p, F8 p, F5 p sekä F8-7 t, muutokset punaisella!! Kotijoukkue (otteluohjelmassa ensin mainittu) järjestää otteluun pelinohjaajan pelipallon sekä huolehtii ottelupöytäkirjan täyttämisestä. F-9 pojat peliaika 2 x 15 min (3 ottelua/peliryhmä) Ott. nro pvm. klo. ikäluokka Aika Koti Vieras Kenttä 160 su.5.8 13:00 F9p 2 X 15 NoPs Valkoinen Hervuudin hurjat Kauppi 2E 161 su.5.8 13:40 F9p 2 X 15 NoPs Harmaa Kaleva Keltainen Kauppi 2E 162 su.5.8 14:20 F9p 2 X 15 NoPs Valkoinen Tesoma Vihreä Kauppi 2E 163 su.5.8 15:00 F9p 2 X 15 Kaleva Keltainen Keskikaupunki Kauppi 2E 164 su.5.8 15:40 F9p 2 X 15 Vehmainen Alfa NoPs Valkoinen Kauppi 2E 165 su.5.8 16:20 F9p 2 X 15 Tesoma Vihreä NoPs Harmaa Kauppi 2E 166 su.5.8 13:00 F9p 2 X 15 Tesoma Vihreä Vehmainen Alfa Kauppi 2F 167 su.5.8 13:40 F9p 2 X 15 Keskikaupunki Annala B Kauppi 2F 168 su.5.8 14:20 F9p 2 X 15 Hervuudin hurjat Vehmainen Alfa Kauppi 2F 169 su.5.8 15:00 F9p 2 X 15 NoPs Harmaa Tesoma Keltainen Kauppi 2F 170 su.5.8 15:40 F9p 2 X 15 Atala Kaleva Vihreä Kauppi 2F 171 su.5.8 16:20 F9p 2 X 15 Keskikaupunki Pirkkala Vihreä Kauppi 2F 172 su.5.8 13:00 F9p 2 X 15 Annala A Atala Kauppi 2G 173 su.5.8 13:40 F9p 2 X 15 Tesoma Keltainen Pirkkala Vihreä Kauppi2G 174 su.5.8 14:20 F9p 2 X 15 Lentävänniemi Atala Kauppi 2G 175 su.5.8 15:00 F9p 2 X 15 Pirkkala Vihreä Annala B Kauppi2G 176 su.5.8 15:40 F9p 2 X 15 Hervuudin hurjat Loiske Kauppi 2G 177 su.5.8 16:20 F9p 2 X 15 Annala B Tesoma Keltainen Kauppi2G 178 su.5.8 13:00 -

Tampereen Kaupungin Hakemus Ympäristöministeriölle Kansallisen Kaupunkipuiston Perustamiseksi Tampereelle

1 (22) Tampereen kaupungin hakemus ympäristöministeriölle kansallisen kaupunkipuiston perustamiseksi Tampereelle 1. Ehdotettu Tampereen kansallisen kaupunkipuiston alue Kansallisista kaupunkipuistoista säädetään maankäyttö-ja rakennuslaissa (132/1999) 68-71 §:ssä. Maankäyttö- ja rakennuslaki (132/1999) 68 § 1 momentti: ”Kaupunkimaiseen ympäristöön kuuluvan alueen kulttuuri- tai luonnonmaiseman kauneuden, luonnon monimuotoisuuden, historiallisten ominaispiirteiden tai siihen liittyvien kaupunkikuvallisten, sosiaalisten, virkistyksellisten tai muiden erityisten arvojen säilyttämiseksi ja hoitamiseksi voidaan perustaa kansallinen kaupunkipuisto.” Tampereen kansallisen kaupunkipuiston hakemus koskee liitekartalla1 rajattua aluetta. Kaupunkipuistoksi rajattu alue perustuu Tampereen tarinaan historiallisena teollisuuskaupunkina järvien ja harjujen maiseman solmukohdassa. Tampereen kansallisen kaupunkipuiston pinta-ala on 3662 hehtaaria, josta Eteläpuisto-Viinikanlahden muutosalueen osuus on 34 hehtaaria. Vesialuetta Tampereen kansallisen kaupunkipuiston alueesta on 63 % (2306 hehtaaria), josta edellämainitun muutosalueen osuus on 25 hehtaaria. Kaupunki omistaa kansallisen kaupunkipuiston rajaukseen kuuluvista alueista 82 % (2989 hehtaaria), josta vesialuetta on 1872 hehtaaria. Kaupunkipuiston maa-alueista 78 % (1059 hehtaaria) on kaavoitettu viher- tai suojelualueeksi, tästä asemakaavoitettua viher- tai suojelualuetta on 33% (345 hehtaaria). Kansallisen kaupunkipuiston alueella sijaitsee kolme luonnonsuojelulain 24 §:n mukaista luonnonsuojelualuetta -

Kaavoitusohjelma 2020‐2024

Kaavoitusohjelma 2020‐2024 KOHDEKORTIT Elina Karppinen, Asemakaavapäällikkö Kaavoitusohjelma 2020 – 2024 Kaupunkiympäristön suunnittelu, Asemakaavoitus 2020 1. Raholan radanvarsikortteli Raholaan rautatien eteläpuoliselle teollisuusalueelle laaditaan asemakaavamuutos valmistella olevan yleissuunnitelman pohjalta. Tavoitteena on kantakaupungin yleiskaavan 2040 mukainen kaupunkimainen alue. • Tesoman aluekeskuksen vahvistaminen • Yhteydet Tesomalta Mediapolikseen ja Hiedanrantaan • Liikennejärjestelyt lähijunaliikenteen, joukkoliikenteen, ajoneuvoliikenteen sekä kävelyn ja pyöräilyn osalta • Uusia asumisen mahdollisuuksia, monipuolisia toimintoja • Ympäristöhäiriöiden torjunta • Laadukas viherympäristö • Asuinkerrosalaa n. 50 000 k-m² ja muuta n. 15 000 k-m² Kaavoitusohjelma 2020 – 2024 Kaupunkiympäristön suunnittelu, Asemakaavoitus 2020 2. Asemakeskus I (asemakaava nro 8640) Alueen kehittämistä tutkitaan vuoden 2014 kansainvälisen suunnittelukilpailun ja käynnissä olevan yleissuunnittelun pohjalta. Eri kulkumuotojen sujuvaa yhdistämistä ja alueen täydennysrakentamisen mahdollisuuksia suunnitellaan tiiviissä yhteistyössä mm. VR-Yhtymän ja Finnpark Oy:n sekä Väyläviraston Tampereen henkilöratapihan kehittämishankkeen (TAHERA) kanssa. Asemakaavojen vaiheistus tarkentuu yleissuunnitelman valmistuttua. Valmisteltavana on samanaikaisesti alueen maanalaisen pysäköinnin ja huollon järjestämistä käsittelevä maanalainen asemakaava nro 8670. • Suunnittelukilpailu 2014 • Eri kulkumuotojen sujuvat yhteydet • Aseman seudun vetovoimaisuus ja imago • Kaupunkitilan -

Matkailijan Kartta Web FI

Naistenlahden voimalaitos Satamatoimisto NÄE JA KOE 6 36 n PAIKALLISEEN TYYLIIN Myllysaari 2 a Kekkosenkatu l Rauhaniementie l Parantolankatu RANTA-TAMPELLA lahdenkatu e kan 11 Näsijärvi Sou2 15 Vieraile Finlaysonin ja Tampellan alueilla ja todista p 19 Kekkosentie m kaupungin teollisuusperinnön uutta elämää. Ihaile 95,2 19 a ARMONKALLIO esplanadi 13 T Soukkapuisto 21 4 Tampereen kansallismaisemaa, historiallisia puna- 16 2 7 1 8 1 2 tiilirakennuksia ja pauhaavaa koskea. Kiipeä T 8 a 7 1 2 7 Särkänniemi 3 4 m Pohjoinen 4 Pyynikinharjulle ja nauti henkeäsalpaavan kau- 2 N Haarakatu 2 11 M m a katu 5 6 8 8 niista maisemista. Maista maailman parhaita o i 2 Välimaanpolku5 13 5 s i 3 e s tu t i Yrjön l Hotel o 6 äka e MATKAILIJAN KARTTA 7 a 25 munkkeja Pyynikin näkötornissa. Piipahda Pispa- 13 n n 17 PohjolankatuKauppi Pajasaari Törngrenin 15 n Ihanakatu k Lepp ratapihankatu 9-11 l Rohdin a 2-4 aukio kuja a lan kaupunginosassa, jossa maisemaa hallitsee p 30 VISITTAMPERE.FI Näsinneula 32 t 33 u h 22 1 15 Pohjolankatu u 11 Verstaankatu 11 2 12 0 Puh: +358 3 5656 6800 d esplanadi 28 5 i kaupungin ehkä kuuluisin, hengästyttävän kaunis 9 62 Kihlmaninraitti s 29 e Siltakatu 4 t 6 n 7 o 1 Akvaario-Planetaario TAMPELLA 10 puutaloalue. k k Osmonkatu 9 14 Keernakatu 2 3 a 24 a t Osmonpuisto t 10. Finlaysonin alue u Runoilijan Tampellan Pajakatu u 9 www.visittampere.fi 1 Pellavan- 14 Kortelahtitie Milavida Auvisenpolku tori Massunkuja 1 Annikinkatu 6 (kattokävelyt: roofwalk.fi) 5 Ainonkatu 6 13 2 13 4 8 1 1 10 1 4 5 1 4 k 6 atu Santalahti Taidekeskus 1 Polvi 7 Mustalahti Juhlatalonkatu 5 20 2 11. -

Kuulutus Tampereen Maanvastaanotto• Ja •Jalostusalueiden Ympäris• Tövaikutusten Arviointiohjelmasta

P I R K A N M A A N Y M P Ä R I S T Ö K E S K U S … … … … … … … … … ... KUULUTUS TAMPEREEN MAANVASTAANOTTO• JA •JALOSTUSALUEIDEN YMPÄRIS• TÖVAIKUTUSTEN ARVIOINTIOHJELMASTA Tampereen kaupunki on toimittanut Pirkanmaan ympäristökeskukselle ympäristövaikutusten arviointime• nettelystä annetun lain mukaisen ympäristövaikutusten arviointiohjelman Tampereen maanvas• taanotto• ja •jalostusalueista (YVA•ohjelma). Ympäristökeskus on YVA•menettelyn yhteysviran• omainen ja ilmoittaa vaikutusalueen kunnissa kuulutuksella ympäristövaikutusten arviointimenettelyn alkamisesta ja YVA•ohjelman vireilläolosta. Arvioitava hanke ja sen vaihtoehdot Arvioitava hankekokonaisuus on Tampereen kaupungin maanvastaanottoalueiden, maa• ja kiviainesten jatkojalostus• ja välivarastointialueiden mukaan lukien hiekoitussepelinpesun ja sadevesikaivojen tyhjen• nyssakkojen käsittelyn sekä taimistojen ja kasvualustan valmistusalueen sijoittaminen ja toiminta Itä•, Etelä• ja Länsi•Tampereelle. Vaihtoehtona selvitetään myös mahdollisuudet muodostaa naapurikuntien kanssa yhteisiä alueita kuntien rajalla. Lisäksi arvioidaan alueiden myöhempää käyttöä esimerkiksi virkis• tysalueina. Itäisen ja eteläisen Tampereen esitetyt vaihtoehdot Lintukallio (Nurmi•Sorila), Kuokkamaa ja Hepovuori (Kauppi•Niihama), Vuores (Lempäälä): maan• vastaanotto ja välivarastointi. Ruskonperä (Hervanta): maanvastaanotto, jatkojalostus• ja välivarastointi, taimisto ja kasvualustan valmistus, hiekoitussepelinpesu ja sadevesikaivojen tyhjennyssakkojen käsittely. Läntisen Tampereen vaihtoehdot Piiriniitty -

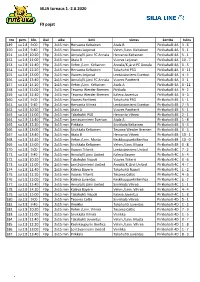

SILJA Turnaus 1.-2.8.2020 F9 Pojat

Ilves Futis-Liiga SILJA turnaus 1.-2.8.2020 F9 pojat nro pvm. klo. ikäl aika koti vieras kenttä tulos 149. su 2.8 9:00 F9p 2x15 min Hervanta Keltainen Atala B Pirkkahalli 4A 3 - 6 150. su 2.8 9:40 F9p 2x15 min Vuores Leijonat Vehm./Linn. Keltainen Pirkkahalli 4A 3 - 1 151. su 2.8 10:20 F9p 2x15 min Annala/K.järvi FC Annala Hervanta Keltainen Pirkkahalli 4A 5 - 1 152. su 2.8 11:00 F9p 2x15 min Atala B Vuores Leijonat Pirkkahalli 4A 10 - 7 153. su 2.8 11:40 F9p 2x15 min Vehm./Linn. Keltainen Annala/K.järvi FC Annala Pirkkahalli 4A 0 - 5 154. su 2.8 12:20 F9p 2x15 min Hervanta Keltainen Takahuhti PSG Pirkkahalli 4A 0 - 11 155. su 2.8 13:00 F9p 2x15 min Vuores Leijonat Lentävänniemi Everton Pirkkahalli 4A 4 - 4 156. su 2.8 13:40 F9p 2x15 min Annala/K.järvi FC Annala Vuores Pantterit Pirkkahalli 4A 3 - 1 157. su 2.8 14:20 F9p 2x15 min Vehm./Linn. Keltainen Atala A Pirkkahalli 4A 0 - 11 158. su 2.8 15:00 F9p 2x15 min Tesoma Werder Bremen Pirkkala Pirkkahalli 4A 9 - 2 159. su 2.8 15:40 F9p 2x15 min Tesoma Werder Bremen Kaleva Juventus Pirkkahalli 4A 4 - 3 160. su 2.8 9:00 F9p 2x15 min Vuores Pantterit Takahuhti PSG Pirkkahalli 4B 1 - 1 161. su 2.8 9:40 F9p 2x15 min Hervanta Vihreä Lentävänniemi Everton Pirkkahalli 4B 7 - 3 162. su 2.8 10:20 F9p 2x15 min Atala A Vuores Pantterit Pirkkahalli 4B 5 - 1 163. -

Tampereen Kaupungin Tilastollinen Vuosikirja 2012-2013

TAMPEREEN KAUPUNGIN TILASTOLLINEN VUOSIKIRJA 2012-2013 TAMPEREEN KAUPUNGIN JULKAISUJA TILASTOT 2014 Tampereen kaupungin tilastollinen vuosikirja 2012–2013 47. vuosikerta Statistical Yearbook of the City of Tampere 2012–2013 th 47 volume Julkaisija: Published by Tampereen kaupunki City of Tampere Konsernihallinto Central administration Hallinto- ja talousryhmä Tietoyksikkö Osoite: PL 487 Address: P.O. Box 487 Aleksis Kiven katu 14 –16 C Aleksis Kiven katu 14 –16 C 33101 Tampere FIN-33101 Tampere Puh. 03 565 611 FINLAND http://www.tampere.fi/tilastot Tel. +358 3 565 611 http://www.tampere.fi/statistics Kannen kuva: Susanna Lyly Kuvat: Satu Aalto, Susanna Lyly, Ari Järvelä, Petri Laitinen, Opa Latvala, Kerttu Liukkala, Ville Palkinen, Simo-Pekko Salminen Juvenes Print – Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2014 3 Tampereen tilastollinen vuosikirja 47. painos Tampereen kaupungin tilastollinen vuosikirja julkaistiin ensimmäisen kerran vuonna 1948. Tämä 47. vuosikerta ilmestyy aikaisempien vuosien tapaan kaksoisnumerona. Tilastollisessa vuosikirjassa 2012–2013 kuvataan Tampe- retta ja tamperelaisia tilastojen valossa. Vuosikirjan sisältöä on muutettu aikojen saatossa hyvin vähän, jotta pitkien aikasarjojen muodostaminen eri vuosien kirjoista olisi mahdollista. Joidenkin taulukoiden sisältö on kuitenkin jouduttu muuttamaan ja joitakin poistamaan kokonaan, koska vertailukelpoisia tietoja niihin ei ole kyetty saamaan. Kulttuuria ja vapaa-aikaa koskevat tilastot on erotettu omaksi luvukseen numerolle 10, kun ne aiemmin olivat koulutuksen kanssa samassa luvussa. Tästä syystä kaikkien tämän jälkeen tulevien taulukoiden numerointi on muuttunut. Tuoreimmat tilastot ovat vuosilta 2012 ja 2013. Useimmissa taulukoissa tiedot ovat vähintään viimeiseltä viisi- vuotiskaudelta tai 2000–luvulta. Joidenkin ilmiöiden osalta myös pitemmät aikasarjat ovat perusteltuja. Vertailua tehdään kaupunkiseudun ja sen kuntien lisäksi Suomen suurimpiin kaupunkeihin ja suurimpiin seutukuntiin. Kuntajakojen muutokset on otettu vertailuissa huomioon.