Deveaux on Tad Hershorn.Granz Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

A JAZZ ODYSSEY: MY LIFE in JAZZ by Oscar Peterson

A JAZZ ODYSSEY: MY LIFE IN JAZZ by Oscar Peterson. Continuum, 382pp, $39.95. Reviewed by John Clare ___________________________________________________________ [This review appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on August 30, 2003.] scar Peterson could make the piano ring with brilliant clarity in all its registers. His command of the jazz vocabulary was magisterial, his swing and O inventive flow almost frightening at times. He has suffered a stroke, but still plays beautifully. His fans are legion. He has been invited into the homes of European nobility to play a treasured instrument after dinner. The head of Steinway sent a piano of his own choosing for Peterson to try when he heard the musician was looking for a new instrument. This is Oscar Peterson's story in his own words. For fans it will deliver uniform satisfaction. For those who do not count him among their three or four favourite jazz pianists, some sections may seem rather cosy and clubby, particularly the chapters dealing with his long stint in impresario Norman Granz's travelling jam session, otherwise known as Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP). 1 Some sections may seem rather cosy and clubby, particularly the chapters dealing with Peterson’s long stint in Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP), organised by impresario Norman Granz (above)… Peterson is intelligent and articulate, and there is a beautifully described scene - a kind of still life within a moving bus - that will bring touring life vividly back to anyone who has been down that road. There are also accounts of pranks - typically involving fart cushions in lifts - where you realise you had to be there but are glad you weren't. -

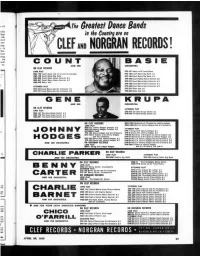

CLEF and NORGRAN RECORDS ’ Blic

ne Breitest Bence Bends ndly that In the Country ere on I ob- nted rec- ncy, 8 to CLEF AND NORGRAN RECORDS ’ blic. ■tion song Host ORCHESTRA ON CLEF RECORDS LONG PUT EPC-157 Dance with Count Basie MGC-120 Count Basle and his Orchestra Collates EPC IOS Count Basie Big Band sr 1 MGC-140 Count Basle Big Band EPC IM Count Basie Big Band sr 2 MGC «26 Count Basle Dance Session #1 EPC-220 Count Basle Dance Session # 1 MGC-G47 Count Basle Dance Session 02 EPC-221 Count Basie Dance Session #2 MGC-833 Basle la» EPC-338 Count Basie Dance Session #3 EXTENDED PUT EPC-338 Count Basle Dance Session #4 EPC-132 Count Basle and His Orchestra #1 EPC-251 Basie Jan #1 EPC-14? Count Basle and His Orchestra #2 EPC 252 Basie Jan #2 ORCHISfRA ON CLEF RECORDS EXTENBEB PUT LONG PUT EPC-247 The Gene Krupa Sextet # 1 MGC-147 The Gene Krupa Sextet #1 EPC-248 The Gene Krupa Sextet #2 MGC-152 The Gene Krupe Sextet #2 MGC 831 The Gene Krupa Sextet #3 ON CLEF RECOROS MGN-1004 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges LONS PUT MGN-10M More of Johnny Hodges end Hli Jrchestra MCC-111 Johnny Hodges Collates #1 MGC-12» Johnny Hodges Collates 02 EXTENOEB PUT EXTENDED PUT (PN-1 Swing with Johnny Hodges #1 EPC-12» Johnny Hodges «nd His Orchestra EPN-2 Swing with Johnny Hodges 02 (PC-148 Al Hibbler with johnny Hodges 6PN 28 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #1 and His Orchestra (PN 27 Memorles of Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #2 EPC 183 Dance with Johnny Hodges #1 EPN-83 More iH Johnny Hodges end His Orchestra O1 EPC 164 Oance with Johnny Hodges #2 (PN-44 Mora of Johnny Hodges -

Jo Jones the Main Man Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jo Jones The Main Man mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Main Man Country: Brazil Released: 1978 Style: Hard Bop MP3 version RAR size: 1767 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1978 mb WMA version RAR size: 1164 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 123 Other Formats: AHX AU VOC DTS WAV WMA DXD Tracklist Hide Credits Goin' To Chicago A1 9:09 Written-By – Basie*, Rushing* I Want To Be Happy A2 4:48 Written-By – Caesar*, Youmans* Adlib A3 8:12 Written-By – Jo Jones Dark Eyes B1 10:20 Arranged By – Buck Clayton Metrical Portions B2 5:51 Written-By – Budd Johnson Old Man River B3 4:25 Written-By – Kern*, Hammerstein* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Pablo Records Recorded At – RCA Recording Studios Mastered At – Kendun Recorders Distributed By – Companhia Brasileira De Discos Phonogram Manufactured By – Companhia Brasileira De Discos Phonogram Credits Bass – Sam Jones Drums – Jo Jones Engineer – Bob Simpson Guitar – Freddie Green Layout, Design – Gribbitt*, Norman Granz Photography By – Phil Stern Piano – Tommy Flanagan Producer – Norman Granz Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Davis* Trombone – Vic Dickenson Trumpet – Harry Edison, Roy Eldridge Notes Série De Luxo Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A): 2310 799 A Matrix / Runout (Side B): 2310 799 A Mould SID Code (Side A): JA 200 2310 799 A1 Mould SID Code (Side B): JA 200 2310 799 B1 Label Code: 3254 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Main Man (LP, 2310-799 Jo Jones Pablo Records 2310-799 US 1977 Album) The Main Man (LP, 2310 -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre. -

Proquest Dissertations

A comparison of embellishments in performances of bebop with those in the music of Chopin Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Mitchell, David William, 1960- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 23:23:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278257 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the miaofillm master. UMI films the text directly fi^om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fi-om any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and contLDuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Diego Rivera Bio 2020

DIEGO RIVERA SAXOPHONIST - COMPOSER - ARRANGER ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF JAZZ SAXOPHONE - MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY “...his playing is carefully phrased and beautifully nuanced…” - Jazz Times A world-class musician, composer, arranger and educator, Diego Rivera has entertained audiences for over 20 years. Rivera is known for his muscular tone and unique blend of straight-ahead mainstream jazz fused with music inspired by his Latino background and heritage. He is a tenured Associate Professor of Jazz Saxophone at Michigan State University where he also serves as Associate Director of Jazz Studies. Rivera was born in Ann Arbor, MI and raised ‘just up the road’ in East Lansing, MI. Born into a Mexican- American family, his Chicano heritage has always been important to him and shaped his creative endeavors. His parents named him after the famed muralist, Diego Rivera. A trip to the Detroit Institute of Arts at a young age inspired him to make his own mark with the Saxophone rather than the brush. He attended Michigan State University where he studied with Andrew Speight, Branford Marsalis, Ron Blake and Rodney Whitaker. In 1999, he began his professional and touring career with the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra on their Big Band ‘99 tour. Since that maiden voyage, he has performed concerts at the most prestigious venues and festivals across the United States, Canada, Europe and Asia. He currently leads his own group, The Diego Rivera Quartet. Rivera has also toured with GRAMMY-Award winning vocalist, Kurt Elling, JUNO-Award winning Canadian Jazz Vocalist, Sophie Milman and The Rodney Whitaker Quintet. He is a member of the The Ulysses Owens Jr. -

An Interview with the Authors, Joshua Berrett and Louis G. Bourgois III -- and the Eminent J.J

An Interview With The Authors, Joshua Berrett And Louis G. Bourgois III -- And The Eminent J.J. Johnson November 1999 By Victor L. Schermer http://www.allaboutjazz.com/iviews/jjjohnson.htm AAJ: Congratulations to Josh and Louis on your new book- and to J.J. for now having a scholarly reference devoted to your outstanding contributions to music. Just for the fun of it, which three recordings and/or scores would you take to the proverbial desert island, if they were to be your only sources of music there? J.J. Johnson: Hindemith's Mathis der Maler, Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe. Any of the Miles Davis Quintet recordings that include Coltrane, Paul Chambers, Philly Joe, and Red Garland. In my opinion, contemporary jazz music does not get any better, or any more quintessential than that Quintet's live appearances or the recorded legacy that they left for us to enjoy. Louis Bourgois: The scores I'd take would be: Aaron Copland, Third Symphony (CD: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin conductor: Angel CDM7643042);. Leonard Bernstein, Chichester Psalms (CD: Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Robert Shaw, conductor; TelArc Digital CD80181). And a Compact Disc: Miles Davis Kind of Blue (Columbia CK40579). I would sneak a few more ;-), including Hindemith, Mathis der Maler, which J.J. mentioned. Joshua Berrett: My tastes here are very similar to J.J's: a mix of classical music and jazz. I would single out Brahms' Symphony No. 2, Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, and Miles Davis' sessions with Coltrane and company. THE BOOK AND ITS AUTHORS AAJ: Josh and Louis, tell us a bit about your musical background. -

ALBUMS EAG -ES, "HOTEL CALIFORNIA" (Prod

DFDICATED TO THE NF SINGLES ALBUMS EAG -ES, "HOTEL CALIFORNIA" (prod. by Bill SPINNERS; "YOU'RE THROWING A GOOD LOVE AMERICA, "HARBOR." This trio has Szymczyk) (writers: Felder -Henley - AWAY" (prod. by Thom Bell) (writ- mastered a form-easy-going, soft rock Frey) (pub. not listed) (6:08). Prob- ers: S. Marshall & T. Wortham) built around three-part harmonies and ably America's hottest group on bath (Mighty Three, BMI) (3:36). The group (on its more recent Ips) the sweet pro- the album and singles levels, The has slowed the tempo from its romp- duction and arrangements of George Eagles have followed the stunning ing "Rubberband Man" but main- Martin. "Don't Cry Baby," -Now She's success of "New Kid In Town" with tains the eclectic sound that has Gone" and "Sergeant Darkness" fill the the title track from their platinum made them a major force through- prescription most eloquently. They'll Ip. A mild reggae flavor pervades out pop and souldom. The track is never be in dry dock. Warner Bros. BSK the tune. Asylum 45386. from their forthcoming Ip. Atl. 3382. 3017 (7.98). THE MANHATTANS, "IT FEELS SO GOOD TO THE ISLEY BROTHERS, "THE PRIDE" (prod. by BAC -ëMAN-TURNER OVERDRIVE, "FREE- ItF LOVED SO BAD' (prod. by The The Isley Brothers) (R. Isley-O. Isley- WAYS." With "Freeways," BTO has Manhattans Co./Bobby Martin) (Raze R. Isley-C. Jasper -E.. Isley-M.Isley) reached a new stage of its career. zle Dazzle, BMI) (3:58). The group (Bovina, ASCAP) (3:25). A growling Hinted at previously _but fully devel- opens the tune with one of its by guitar and loping bass sound sets oped now, the group has retained its now obligatory narrative exhorta- the pace for the group's best effort power while moving to a more melody tions which sets the tors.