Ethiopia's Election and Abiy's Political Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Ethiopia Elections 2021: Journalist Safety Kit

Ethiopia elections 2021: Journalist safety kit Ethiopia is scheduled to hold general elections later this year amid heightened tensions across the country. Military conflict broke out in the Tigray region in November 2020, and is ongoing; over the past year, several other regions have witnessed significant levels of violence and fatalities as a result of protests and inter-ethnic clashes, according to media reports. Voters line up to cast their votes in Ethiopia's general election on May 24, 2015, in Addis Ababa, the capital. Ethiopians will vote in general elections later in 2021. (AP/Mulugeata Ayene) At least seven journalists were behind bars in Ethiopia as of December 1, 2020, according to CPJ research, and authorities are clamping down on critical media outlets, as documented by CPJ and media reports. The statutory regulator, the Ethiopia Media Authority, withdrew the credentials of New York Times correspondent Simon Marks in March and later expelled him from the country, alleging unbalanced coverage. The regulator has sent warnings to media outlets and agencies, including The Associated Press, for their reporting on the Tigray conflict, according to media reports. Journalists and media workers covering the elections anywhere in Ethiopia should be aware of a number of risks, including--but not limited to--communication blackouts; getting caught up in violent protests, inter-ethnic clashes, and/or military operations; physical harassment and 1 intimidation; online trolling and bullying; and government restrictions on movement, including curfews. CPJ Emergencies has compiled this safety kit for journalists covering the elections. The kit contains information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for the general election cycle, and how to mitigate physical and digital risk. -

“The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia”

Statement of Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs Before Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations U.S. House of Representatives Hearing on “The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia” December 1, 2020 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov <Product Code> {222A0E69-13A2-4985-84AE-73CC3D FF4D02}-TE-163211152070077203169089227252079232131106092075203014057180128125130023132178096062140209042078010043236175242252234126132238088199167089206156154091004255045168017025130111087031169232241118025191062061197025113093033136012248212053148017155066174148175065161014027044011224140053166050 Congressional Research Service 1 Overview The outbreak of hostilities in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November reflects a power struggle between the federal government of self-styled reformist Prime Minister Abiy (AH-bee) Ahmed and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a former rebel movement that dominated Ethiopian politics for more than a quarter century before Abiy’s ascent to power in 2018.1 The conflict also highlights ethnic tensions in the country that have worsened in recent years amid political and economic reforms. The evolving conflict has already sparked atrocities, spurred refugee flows, and strained relations among countries in the region. The reported role of neighboring Eritrea in the hostilities heightens the risk of a wider conflict. After being hailed for his reforms and efforts to pursue peace at home and in the region, Abiy has faced growing criticism from some observers who express concern about democratic backsliding. By some accounts, the conflict in Tigray could undermine his standing and legacy.2 Some of Abiy’s early supporters have since become critics, accusing him of seeking to consolidate power, and some observers suggest his government has become increasingly intolerant of dissent and heavy-handed in its responses to law and order challenges.3 Abiy and his backers argue their actions are necessary to preserve order and avert further conflict. -

6. Oromo Liberation Front

Country Information and Policy Note Ethiopia: Opposition to the government Version 1.0 December 2016 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this note has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve our material. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this note, please email the Country Policy and Information Team. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

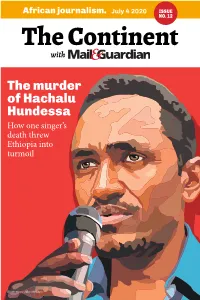

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

Notiz Äthiopien: Qeerroo-Bewegung Und Machtverhältnisse in Lokalverwaltungen Des Regionalstaats Oromia (07.05.2020)

Eidgenössisches Justiz- und Polizeidepartement EJPD Staatssekretariat für Migration SEM Sektion Analysen Öffentlich Bern-Wabern, 7. Mai 2020 Notiz Äthiopien Qeerroo-Bewegung und Machtverhältnisse in Lokalverwaltungen des Regionalstaats Oromia Öffentlich Inhaltsverzeichnis Fragestellung ....................................................................................................................... 3 Kernaussage ........................................................................................................................ 3 Main findings........................................................................................................................ 3 1. Quellenlage ............................................................................................................. 4 2. Die Qeerroo-Bewegung ......................................................................................... 4 3. Lage während der SEM-Abklärungsreise (Mai 2019) ........................................... 6 4. Jawar Mohammeds Hinwendung zum OFC ......................................................... 7 5. Lage in den Lokalverwaltungen Anfang 2020 ...................................................... 8 6. Kommentar ............................................................................................................. 9 6.1. Legitimität staatlichen Einschreitens......................................................................... 9 6.2. Ausblick .................................................................................................................. -

Development and Humanitarian Issues

Press Review 10 October 2017 - 17 February 2018 Deutsch-Äthiopischer Verein Press Review - Nachrichten und Meinungen aus und zu Äthiopien 10. Oktober 2017 - 17. Februar 2018 Development and Humanitarian Issues ............................................................................................. 1 Politics, Justice, Human Rights ......................................................................................................... 9 Economics ..................................................................................................................................... 103 Environment, Agriculture and Natural Resources .......................................................................... 112 Media, Culture, Religion, Education, Social and Health ................................................................ 116 Sport .............................................................................................................................................. 121 Horn of Africa and Foreign Affairs ................................................................................................. 121 Development and Humanitarian Issues 8.2.2018 UNDP and OCHA Chiefs renew call for new way of working . ReliefWeb, UNDP Report of 31.1.2018 Breaking down the silos between humanitarian and development actors to address recurrent crises The Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Achim Steiner and the United Nations Under-Secretary- General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark -

The Discursive Construction of Identity: the Case of Oromo in Ethiopia

i The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Eight departments, associated research institutions and the Norwegian College of Veterinary Medicine in Oslo. Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master thesis are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master programme “International Environmental Studies”, “International Development Studies” and “International Relations”. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. © Yosef Tadesse Ayele, May 2016 [email protected] Noragric, Department of International Environment and Development Studies P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 64 96 52 00 Fax: +47 64 96 52 01 Internet: http://www.nmbu.no/noragric ii Declaration I, Yosef Tadesse Ayele, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. Signature……………………………….. Date: iii Abstract Identity politics in Ethiopia is not a recent phenomenon. It has been one of the major mobilizing factor in the entire modern history. However, the institutionalization and the establishment of the issue in the policy and legal documents of the nation has started in 1991 when the current government: EPRDF, came to power. -

Qeerroo Fi Qaarree Oromoo” Irreversible Victories in the History of Oromo Struggle for Equality in Ethiopia

GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 5, May 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 1085 GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 5, May 2021, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com “QEERROO FI QAARREE OROMOO” IRREVERSIBLE VICTORIES IN THE HISTORY OF OROMO STRUGGLE FOR EQUALITY IN ETHIOPIA. By: Solomon Dessalegn Dibaba (LLB, LLM) March 2021 GSJ© 2021 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 5, May 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 1086 Table of contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….1 2. Oromo Gadaa System (Oromo Democracy)…………………………………………………………………….2 3. The Occupation of Oromo and Oromia by the Northern Ruling Class……………………………….4 4. The Tragedy of Oromo Continued under TPLF led EPRDF Government…………………..........7 5. Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) Holocaust by Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF)………9 6. “Qeerroo fi Qaarree Oromoo” Struggle in the Contemporary History of Ethiopia……………12 7. The Victory of ‘Qeerroo fi Qaarree’ Oromo and its Consequences…………………………………..20 8. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….26 Page i GSJ© 2021 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 5, May 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 1087 Abstract This article is about Oromo’s restless long walk struggle for freedom, equality, and democracy. The article clearly shows the cruelty, inhumanity and horrific administration of Amharan-Tigray tyrant/fascist/dictator governors against democratic and peace loving Oromo nation in the horn of Africa. Also the article indicates that the restless and uninterrupted struggles of Oromo for generations were not successful especial to addresses basic issues of self governance and equitable representation. In other way Oromo’s colonized by Amhara-Tigray tyrant/fascist/dictator governors unable to clear them out completely even though they are fighting fiercely and restlessly for generations to ultimate victory. -

En En Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2014-2019 Plenary sitting B8-0369/2017 16.5.2017 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for a debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 135 of the Rules of Procedure on Ethiopia, notably the case of Dr Merera Gudina (2017/2682(RSP)) Charles Tannock, Karol Karski, Ryszard Antoni Legutko, Ryszard Czarnecki, Tomasz Piotr Poręba, Notis Marias, Ruža Tomašić, Jussi Halla-aho, Raffaele Fitto, Arne Gericke, Angel Dzhambazki, Pirkko Ruohonen-Lerner, Branislav Škripek, Monica Macovei on behalf of the ECR Group RE\P8_B(2017)0369_EN.docx PE605.468v01-00 EN United in diversity EN B8-0369/2017 European Parliament resolution on Ethiopia, notably the case of Dr Merera Gudina (2017/2682(RSP)) The European Parliament, - having regard to its previous resolutions on the situation in Ethiopia; - having regard to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by Ethiopia in the year 1993; - having regard to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; - having regard to the statement of 23 December 2015 by the EEAS on recent clashes in Ethiopia; - having regard to the statement of 10 October 2016 by the Spokesperson of the HR/ VP on Ethiopia's announcement of a state of emergency - having regard the latest Universal Periodic Review on Ethiopia before the UN Human Rights Council; - having regard to the US State Department statement of 18 December 2015 on clashes in Oromia, Ethiopia; - having regard to the EU-Ethiopia Strategic Engagement - having regard to the African Charter of Human and Peoples’ Rights, - having regard to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, - having regard to the Cotonou Agreement, - having regard to Rules 123(4) and 135(5) of its Rules of Procedure; A.