“The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Managing Ethiopia's Transition

Managing Ethiopia’s Unsettled Transition $IULFD5HSRUW1 _ )HEUXDU\ +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Crisis ........................................................................................................... 2 A. Popular Protests and Communal Clashes ................................................................. 3 B. The EPRDF’s Internal Fissures ................................................................................. 6 C. Economic Change and Social Malaise ....................................................................... 8 III. Abiy Ahmed Takes the Reins ............................................................................................ 12 A. A Wider Political Crisis .............................................................................................. 12 B. Abiy’s High-octane Ten Months ................................................................................ 15 IV. Internal Challenges and Opportunities ............................................................................ 21 A. Calming Ethnic and Communal Conflict .................................................................. -

Ethiopia Elections 2021: Journalist Safety Kit

Ethiopia elections 2021: Journalist safety kit Ethiopia is scheduled to hold general elections later this year amid heightened tensions across the country. Military conflict broke out in the Tigray region in November 2020, and is ongoing; over the past year, several other regions have witnessed significant levels of violence and fatalities as a result of protests and inter-ethnic clashes, according to media reports. Voters line up to cast their votes in Ethiopia's general election on May 24, 2015, in Addis Ababa, the capital. Ethiopians will vote in general elections later in 2021. (AP/Mulugeata Ayene) At least seven journalists were behind bars in Ethiopia as of December 1, 2020, according to CPJ research, and authorities are clamping down on critical media outlets, as documented by CPJ and media reports. The statutory regulator, the Ethiopia Media Authority, withdrew the credentials of New York Times correspondent Simon Marks in March and later expelled him from the country, alleging unbalanced coverage. The regulator has sent warnings to media outlets and agencies, including The Associated Press, for their reporting on the Tigray conflict, according to media reports. Journalists and media workers covering the elections anywhere in Ethiopia should be aware of a number of risks, including--but not limited to--communication blackouts; getting caught up in violent protests, inter-ethnic clashes, and/or military operations; physical harassment and 1 intimidation; online trolling and bullying; and government restrictions on movement, including curfews. CPJ Emergencies has compiled this safety kit for journalists covering the elections. The kit contains information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for the general election cycle, and how to mitigate physical and digital risk. -

October 2016 Newsletter

The Monthly Publication from the Ethiopian Embassy in London Ethiopian News October 2016 Issue Inside this issue Book Launch with Joanna Lumley--------------------------------------------------------------------------4 Ethiopia’s Prof. Sebsebe Demissew awarded prestigious Kew International Medal---------5 New project to support youth, women launched-------------------------------------------------------7 Ethiopia to build 120 million passenger airport-------------------------------------------------------9 Simien Lodge wins tourism award-------------------------------------------------------------------------9 Ethiopian films featured at Film Africa 2016-----------------------------------------------------------10 Tirunesh Dibaba wins Great South Run------------------------------------------------------------------11 Five cities leading on climate action – Addis Ababa--------------------------------------------------13 PM Hailemariam Announces New Cabinet Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn announced PM Hailemariam, in the reshuffle, shelved the role 21 new cabinet ministers after he received of Advisor to the Prime Minister with ministerial parliamentary approval from the House of People’s rank as well as the coordinating clusters previously Representatives. held under the Deputy Prime Minister’s portfolio. The new ministers were selected based on their The House also approved the Prime Minister’s knowledge, experience and record on delivery in proposals establishing a department for varying capacities. democratisation aimed at addressing -

Confict Resolution

AFRICAN JOURNAL ON CONFLICT RESOLUTION Volume 16, Number 2, 2016 Efficacy of top-down approaches to post-conflict social coexistence and community building: Experiences from Zimbabwe ‘There’s no thing as a whole story’: Storytelling and the healing of sexual violence survivors among women and girls in Acholiland, northern Uganda Volume 16, Number 2, 2016 Number 2, 2016 16, Volume Competing orders and conflicts at the margins of the State: Inter-group conflicts along the Ethiopia-Kenya border Indigenous institutions as an alternative conflict resolution mechanism in eastern Ethiopia: The case of the Ittu Oromo and Issa Somali clans African Journal on Conflict Resolution Volume 16, Number 2, 2016 The African Journal on Conflict Resolution is a peer-reviewed journal published by the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) for the multidisciplinary subject field of conflict resolution. There are two regular issues per year, and occasionally also a special issue on a particular theme. It appears on the list of journals accredited by the South African Department of Higher Education and Training. ACCORD is a non-governmental, non-aligned conflict resolution organisation based in Durban, South Africa. ACCORD is constituted as an education trust. The journal seeks to publish articles and book reviews on subjects relating to conflict, its management and resolution, as well as peacemaking, peacekeeping and peacebuilding in Africa. It aims to be a conduit between theory and practice. Views expressed in this journal are not necessarily those of ACCORD. While every attempt is made to ensure that the information published here is accurate, no responsibility is accepted for any loss or damage that may arise out of the reliance of any person upon any of the information this journal contains. -

Ethiopian Perspective Artical Name : Elections in Strained Dynamics Artical Subject : 01/07/2021 Publish Date: Anwar Ibrahim

Artical Name : Ethiopian Perspective Artical Subject : Elections in Strained Dynamics Publish Date: 01/07/2021 Auther Name: Anwar Ibrahim Subject : The election, which was held in Ethiopia on Monday, June 21, 2021, was the most complicated election that the country has witnessed in more than three decades, or, more accurately, since the 1994 constitution was approved. The reason is that this election was held amid lots of internal challenges, not to mention the strong criticism of its legitimacy (both domestically and internationally) even before it was held. Ethiopians are warily looking forward to the results, which are supposed to be announced within a few days, despite that it is not unlikely that these results will escalate the tensions in an already unrest-ridden country. Elections in contextOver the past two decades, Ethiopia held five parliamentary elections; where the parliament exercises its power for a period of five years, according to the Ethiopian constitution. In all of these elections, electoral integrity was called into question, and public disorder took place in some regions and provinces. Furthermore, some political parties boycotted these elections, whereas others were prevented from participating on some pretext or other. As for the current election, it took place one year later than it was supposed to be held; On June 10, 2020, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the House of Federation (the highest constitutional authority) approved a decision to postpone the election and extend the term of the federal parliament, the government, and all the federal and provincial assemblies. It also stipulated that once the Ministry of Health announces that the pandemic is under control, arrangements must be made for holding the elections within nine months, or a year at most. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Addis, Amsalu K.; Asongu, Simplice; Zhu, Zuping; Addis, Hailu Kendie; Shifaw, Eshetu Working Paper The recent political situation in Ethiopia and rapprochement with Eritrea AGDI Working Paper, No. WP/20/036 Provided in Cooperation with: African Governance and Development Institute (AGDI), Yaoundé, Cameroon Suggested Citation: Addis, Amsalu K.; Asongu, Simplice; Zhu, Zuping; Addis, Hailu Kendie; Shifaw, Eshetu (2020) : The recent political situation in Ethiopia and rapprochement with Eritrea, AGDI Working Paper, No. WP/20/036, African Governance and Development Institute (AGDI), Yaoundé This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/228008 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu A G D I Working Paper WP/20/036 The Recent Political Situation in Ethiopia and Rapprochement with Eritrea 1 Forthcoming: African Security Review Amsalu K. -

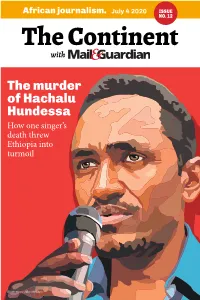

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side). -

OAE7-112018.Pdf

Observatoire friqu de l’ st AEnjeux politiques & Esécuritaires L’Éthiopie d’Abiy Ahmed Ali : une décompression autoritaire Jeanne Aisserge chercheure indépendante & Jean-Nicolas Bach directeur du CEDEJ Khartoum (MEAE-CNRS, USR 3123) Note analyse 7 Novembre 2018 L’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est (2017- 2010) est un programme de recherche coordonné par le Centre d’Etude et de Docu- mentation Economique, Juridique et Sociale de Khartoum (MAEDI-CNRS USR 3123) et le Centre de Recherches Internationales de Sciences Po Paris. Il se situe dans la continuité de l’Observa- toire de la Corne de l’Afrique qu’il remplace et dont il élargit le champ d’étude. L’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est a vocation à réaliser et à diffuser largement des Notes d’analyse relatives aux questions politiques et sécuritaires contempo- raines dans la région en leur offrant d’une part une perspective histo- rique et d’autre part des fondements empiriques parfois négligées ou souvent difficilement accessibles. L’Observatoire est soutenu par la Direction Générale des Relations Internationales et de la Stratégie (ministère de la Défense français). Néanmoins, les propos énoncés dans les études et Observatoires commandés et pilotés par la DGRIS ne sauraient engager sa respon- sabilité, pas plus qu’ils ne reflètent une prise de position officielle du ministère de la Défense. Il s’appuie par ailleurs sur un large réseau de partenaires : l’Institut français des relations internationales, le CFEE d’Addis-Abeba, l’IFRA Nairobi, le CSBA, LAM-Sciences Po Bordeaux, et le CEDEJ du Caire. Les notes de l’Observatoire de l’Afrique de l’Est sont disponibles en ligne sur le site de Sciences Po Paris. -

Ethiopia National Day Special Strong Growth Continues for African Success Story

Ethiopia National Day Special Strong growth continues for African success story CHAM UGALA URIAT tion was put into place that provided a fed- roads and railway networks to facilitate invest in our country. AMBASSADOR OF ETHIOPIA eral system of government that recognized business and trade within the country, as In this connection, I would like to use the rights of all nations, nationalities and well as with its neighbors. this opportunity to extend my thanks and On behalf of the peoples of the country. The government Ethiopia treasures the long-standing appreciation to the friendly people and people and govern- of Ethiopia followed an inward-looking relations it has with the people and gov- government of Japan for being partners ment of the Federal policy of identifying our internal vulner- ernment of Japan. Japan has been a friend and friends to Ethiopia throughout the Democratic Repub- abilities and embarked upon the task of and a development partner to Ethiopia years. lic of Ethiopia and lifting its citizens out of abject poverty throughout their diplomatic history. It has Finally, on this happy occasion, I wish to myself, I would and introducing reforms that were aimed been consistent and reliable in providing reiterate my government’s readiness to fur- like to extend my toward that end. support for our developmental endeavors ther bolster our bilateral cooperation with humble wishes for We have been living a success story ever in line with our policy priorities. Japan for the benefit of our two countries. the good health and since. In fact, Ethiopia has been named one Japan has also been working together happiness, as well of the African ‘’economic miracles’’ for reg- with Ethiopia and countries in our region This content was compiled in collaboration as the continued success and prosperity, of istering one of the fastest rates of economic to tackle regional, continental and interna- with the embassy.