The Discursive Construction of Identity: the Case of Oromo in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Jawar Mohammed Biography: the Interesting Profile of an Influential Man

Jawar Mohammed Biography: The Interesting Profile of an Influential Man Jawar Mohammed is the energetic, dynamic and controversial political face of the majority of young Ethiopian Oromo’s, who now have been given the green light to freely participate in the country’s changing political scene. It is evident that he now has a wide reaching network that spans across continents, namely, the Americas, Europe, and obviously Africa. Jawar has perfected the art of disseminating his views to reach his massive audience base through the expert use of the many media outlets, some of which he runs. His OMN (Oromia Media Network) was a constant source of information for those hoping to hear and watch the news from a TV broadcast that was not associated with the government. Furthermore, Jawar’s handling of Facebook with a following of no less than 1.2 million people, as well as, his skillful use of various other social media tools has helped firmly place him as an important and influential leader in today's ever changing Ethiopian political landscape. Jawar Mohammed: Childhood Jawar Mohammed was born in Dumuga (Dhummugaa), a small and quiet rural town located on the border of Hararghe and Arsi within the Oromia region of Ethiopia. His parents were considered to be one of the first in the area to have an inter-religious marriage. Some estimates claim that Dumuga, is largely an Islamic town, with over 90% of the population adhering to the Muslim faith. His father being a Muslim opted to marry a Christian woman, thereby; the young couple destroyed one of the age old social norms and customs in Dumuga. -

Ethiopia Elections 2021: Journalist Safety Kit

Ethiopia elections 2021: Journalist safety kit Ethiopia is scheduled to hold general elections later this year amid heightened tensions across the country. Military conflict broke out in the Tigray region in November 2020, and is ongoing; over the past year, several other regions have witnessed significant levels of violence and fatalities as a result of protests and inter-ethnic clashes, according to media reports. Voters line up to cast their votes in Ethiopia's general election on May 24, 2015, in Addis Ababa, the capital. Ethiopians will vote in general elections later in 2021. (AP/Mulugeata Ayene) At least seven journalists were behind bars in Ethiopia as of December 1, 2020, according to CPJ research, and authorities are clamping down on critical media outlets, as documented by CPJ and media reports. The statutory regulator, the Ethiopia Media Authority, withdrew the credentials of New York Times correspondent Simon Marks in March and later expelled him from the country, alleging unbalanced coverage. The regulator has sent warnings to media outlets and agencies, including The Associated Press, for their reporting on the Tigray conflict, according to media reports. Journalists and media workers covering the elections anywhere in Ethiopia should be aware of a number of risks, including--but not limited to--communication blackouts; getting caught up in violent protests, inter-ethnic clashes, and/or military operations; physical harassment and 1 intimidation; online trolling and bullying; and government restrictions on movement, including curfews. CPJ Emergencies has compiled this safety kit for journalists covering the elections. The kit contains information for editors, reporters, and photojournalists on how to prepare for the general election cycle, and how to mitigate physical and digital risk. -

Nation Formation and Legitimacy

International Journal of Academic Multidisciplinary Research (IJAMR) ISSN: 2643-9670 Vol. 4, Issue 6, June – 2020, Pages: 52-58 Nation Formation and Legitimacy: The Case of Ethiopia Getachew Melese Belay University of International Business and Economics School of International Relation, Beijing Email Address: [email protected], cell phone+8618513001139/+251944252379 Abstract: This paper attempted to examines how nation formation of Ethiopian undergone and legitimate under the Empire, Military and EPRDF regimes. Accordingly, the paper argues that there are changes and continuities in nation formation of Ethiopian under Empire, military and EPRDF regimes. The study used secondary source of data; collected from books, journal articles, published and unpublished materials, governmental and non-governmental organization reports and remarks, magazines and web sources. To substantiate and supplement the secondary data, the paper also used primary data collected through few key informant interviews. Given the data gathered are qualitative, the study employed qualitative data analysis techniques. The finding of the study revealed that the legitimacy of every regime has their own explanation during monarchy it was that most of the population believed in Jesus Christ so that belief was that king came from God and accept that is divine rule and also the church was doing that. When we come to the recent even if the Derg regime has done land reform but has some defects one not seriously (radically) implemented throughout the country and farmers were not able to use their product. But special after 1991 it was radical land reform and other like democracy, multi-party system and decentralization also contributed for the government to be legitimate. -

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project Comparative Approach Daniel Gemtessa Oct, 2014 Department of Political Sience University of Oslo TABLE OF CONTENTS No.s Pages Part I 1 1 Chapter I Introduction 1 1.1 Problem Presentation – Ethiopia 1 1.2 Concept Clarification 3 1.2.1 Ethiopia 3 1.2.2 Abyssinia Functional Differentiation 4 1.2.3 Religion 6 1.2.4 Language 6 1.2.5 Economic Foundation 6 1.2.6 Law and Culture 7 1.2.7 End of Zemanamesafint (Era of the Princes) 8 1.2.8 Oromos, Functional Differentiation 9 1.2.9 Religion and Culture 10 1.2.10 Law 10 1.2.11 Economy 10 1.3 Method and Evaluation of Data Materials 11 1.4 Evaluation of Data Materials 13 1.4.1 Observation 13 1.4.2 Copyright Provision 13 1.4.3 Interpretation 14 1.4.4 Usability, Usefulness, Fitness 14 1.4.5 The Layout of This Work 14 Chapter II Theoretical Background 15 2.1 Introduction 15 2.2 A Short Presentation of Rokkan’s Model as a Point of Departure for 17 the Overall Problem Presentation 2.3 Theoretical Analysis in Four Chapters 18 2.3.1 Territorial Control 18 2.3.2 Cultural Standardization 18 2.3.3 Political Participation 19 2.3.4 Redistribution 19 2.3.5 Summary of the Theory 19 Part II State Formation 20 Chapter III 3 Phase I: Penetration or State Formation Process 20 3.0.1 First: A Short Definition of Nation 20 3.0.2 Abyssinian/Ethiopian State Formation Process/Territorial Control? 21 3.1 Menelik (1889 – 1913) Emperor 21 3.1.1 Introduction 21 3.1.2 The Colonization of Oromo People 21 3.2 Empire State Under Haile Selassie, 1916 – 1974 37 -

“The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia”

Statement of Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs Before Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations U.S. House of Representatives Hearing on “The Unfolding Conflict in Ethiopia” December 1, 2020 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov <Product Code> {222A0E69-13A2-4985-84AE-73CC3D FF4D02}-TE-163211152070077203169089227252079232131106092075203014057180128125130023132178096062140209042078010043236175242252234126132238088199167089206156154091004255045168017025130111087031169232241118025191062061197025113093033136012248212053148017155066174148175065161014027044011224140053166050 Congressional Research Service 1 Overview The outbreak of hostilities in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November reflects a power struggle between the federal government of self-styled reformist Prime Minister Abiy (AH-bee) Ahmed and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a former rebel movement that dominated Ethiopian politics for more than a quarter century before Abiy’s ascent to power in 2018.1 The conflict also highlights ethnic tensions in the country that have worsened in recent years amid political and economic reforms. The evolving conflict has already sparked atrocities, spurred refugee flows, and strained relations among countries in the region. The reported role of neighboring Eritrea in the hostilities heightens the risk of a wider conflict. After being hailed for his reforms and efforts to pursue peace at home and in the region, Abiy has faced growing criticism from some observers who express concern about democratic backsliding. By some accounts, the conflict in Tigray could undermine his standing and legacy.2 Some of Abiy’s early supporters have since become critics, accusing him of seeking to consolidate power, and some observers suggest his government has become increasingly intolerant of dissent and heavy-handed in its responses to law and order challenges.3 Abiy and his backers argue their actions are necessary to preserve order and avert further conflict. -

Ethiopia COI Compilation

BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Ethiopia: COI Compilation November 2019 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord This report was commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Background information ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Geographical information .................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Map of Ethiopia ........................................................................................................... -

The Polemics and Politics of Ethiopia's Disintegration

Main Page Commentary The Polemics and Politics of Ethiopia’s Disintegration Mukerrem Miftah December 31, 2018 Facebook Twitter Google+ Yazdır Disintegration, or more precisely secession, has been one of the most uninterruptedly recycled themes in the modern political history of Ethiopia. Different political groups, with vested interests in the country, used, redened, and channeled it through various ways under different circumstances. In the post-monarchical Ethiopia, the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), and others went to the extent of taking up arms for what they believed was in the best interests of the people whom they supposedly represent. Bear with me, I have not forgotten, and thus, ruled out Eritrea from this brainstorming exercise. The case of Eritrea can, and denitely, serve a very salient purpose shortly. From the outset, their claims were crystal-clear: a marked dissatisfaction with the existing political order in Ethiopia, and due to which, they opted for independence. Before proceeding further, however, let us raise some important questions worth asking here: Was it, and still is, a question of sine qua non importance in Ethiopia? Can historical, geographical, sociological, economic, and political infrastructures vouch for it? Can we make a relatively weighty distinction between the rhetorical, polemical or strategic deployment of “disintegration” or secession and its actuality on the ground as in the case with the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) or today’s PFDJ of Eritrea? The following paragraphs provide a preliminary engagement with these questions. The Pretexts of Disintegration Ethiopia as a country of multiple identities is a recent phenomenon. -

Prevalence of Bovine Cysticercosis at Holeta Municipality Abattoir and Taenia Saginata at Holeta Town and Its Surroundings, Central Ethiopia

Research Article Journal of Veterinary Science & Technology Volume 12:3, 2020 ISSN: 2157-7579 Open Access Prevalence of Bovine Cysticercosis at Holeta Municipality Abattoir and Taenia Saginata at Holeta Town and its Surroundings, Central Ethiopia Seifu Hailu* Ministry of Agriculture, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Abstract A cross section study was conducted during November 2011 to March 2012 to determine the prevalence of Cysticercosis in animals, Taeniasis in human and estimate the worth of Taeniasis treatment in Holeta town. Active abattoir survey, questionnaire survey and inventories of pharmaceutical shops were performed. From the total of 400 inspected animals in Holeta municipality abattoir, 48 animals had varying number of C. bovis giving an overall prevalence 12% (48/400). Anatomical distribution of the cyst showed that highest proportions of C. bovis cyst were observed in tongue, followed by masseter, liver and shoulder heart muscles. Of the total of 190 C. bovis collected during the inspection, 89(46.84%) were found to be alive while other 101 (53.16%) were dead cysts. Of the total 70 interviewed respondents who participated in this study, 62.86% (44/70) had contract T. saginata Infection, of which, 85% cases reported using modern drug while the rest (15%) using traditional drug. The majority of the respondent had an experience of raw meat consumption as a result of traditional and cultural practice. Human Taeniasis prevalence showed significant difference (p<0.05) with age, occupational risks and habit of raw meat consumption. Accordingly individuals in the adult age groups, occupational high risk groups and habit of raw meat consumers had higher odds of acquiring Taeniasis than individuals in the younger age groups, occupational law risk groups and cooked meat consumers, respectively. -

High Prevalence of Bovine Tuberculosis in Dairy Cattle in Central Ethiopia: Implications for the Dairy Industry and Public Health

High Prevalence of Bovine Tuberculosis in Dairy Cattle in Central Ethiopia: Implications for the Dairy Industry and Public Health Rebuma Firdessa1.¤, Rea Tschopp1,4,6., Alehegne Wubete2., Melaku Sombo2, Elena Hailu1, Girume Erenso1, Teklu Kiros1, Lawrence Yamuah1, Martin Vordermeier5, R. Glyn Hewinson5, Douglas Young4, Stephen V. Gordon3, Mesfin Sahile2, Abraham Aseffa1, Stefan Berg5* 1 Armauer Hansen Research Institute, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2 National Animal Health Diagnostic and Investigation Center, Sebeta, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 3 School of Veterinary Medicine, University College Dublin, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, 4 Centre for Molecular Microbiology and Infection, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 5 Department for Bovine Tuberculosis, Animal Health and Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Weybridge, Surrey, United Kingdom, 6 Swiss Tropical and Public Health, Basel, Switzerland Abstract Background: Ethiopia has the largest cattle population in Africa. The vast majority of the national herd is of indigenous zebu cattle maintained in rural areas under extensive husbandry systems. However, in response to the increasing demand for milk products and the Ethiopian government’s efforts to improve productivity in the livestock sector, recent years have seen increased intensive husbandry settings holding exotic and cross breeds. This drive for increased productivity is however threatened by animal diseases that thrive under intensive settings, such as bovine tuberculosis (BTB), a disease that is already endemic in Ethiopia. Methodology/Principal Findings: An extensive study was conducted to: estimate the prevalence of BTB in intensive dairy farms in central Ethiopia; identify associated risk factors; and characterize circulating strains of the causative agent, Mycobacterium bovis. The comparative intradermal tuberculin test (CIDT), questionnaire survey, post-mortem examination, bacteriology, and molecular typing were used to get a better understanding of the BTB prevalence among dairy farms in the study area. -

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: the Political Situation

Report of a Home Office Fact-Finding Mission Ethiopia: The political situation Conducted 16 September 2019 to 20 September 2019 Published 10 February 2020 This project is partly funded by the EU Asylum, Migration Contentsand Integration Fund. Making management of migration flows more efficient across the European Union. Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 Background ............................................................................................................ 5 Purpose of the mission ........................................................................................... 5 Report’s structure ................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 6 Identification of sources .......................................................................................... 6 Arranging and conducting interviews ...................................................................... 6 Notes of interviews/meetings .................................................................................. 7 List of abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Executive summary .................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis of notes ................................................................................................ -

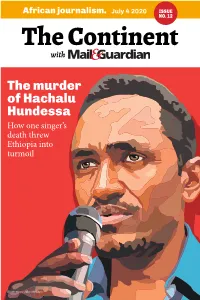

The Continent ISSUE 12

African journalism. July 4 2020 ISSUE NO. 12 The Continent with The murder of Hachalu Hundessa How one singer’s death threw Ethiopia into turmoil Illustration: John McCann Graphic: JOHN McCANN The Continent Page 2 ISSUE 12. July 4 2020 Editorial Abiy Ahmed’s greatest test When Abiy Ahmed became prime accompanying economic crisis, from minister of Ethiopia in 2018, he made which Ethiopia is not spared. the job look easy. Within months, he had released thousands of political All this occurs against prisoners; unbanned independent media and opposition groups; fired officials the backdrop of the implicated in human rights abuses; and global pandemic and made peace with neighbouring Eritrea. the accompanying Last year, he was rewarded with the economic crisis Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his efforts in brokering that peace. But the job of prime minister is never The future of 109-million Ethiopians easy, and now Abiy faces two of his now depends on what Abiy and his sternest tests – simultaneously. administration do next. The internet With the rainy season approaching, and information blackout imposed this Ethiopia is about to start filling the week, along with multiple reports of Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam brutality from state security forces and on the Blue Nile. No deal has been the arrests of key opposition leaders, are concluded with Egypt and Sudan, who a worrying sign that the government are both totally reliant on the waters of is resorting to repression to maintain the Nile River, and regional tensions are control. rising fast. Prime Minister Abiy was more than And then, this week, the assassination happy to accept the Nobel Peace Prize of Hachalu Hundessa (p15), an iconic last year, even though that peace deal singer and activist, sparked a wave of with Eritrea had yet to be tested (its key intercommunal conflict and violent provisions remain unfulfilled by either protests that threatens to upend side).