Common Tern Recovery Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 North Atlantic Hurricane Season Review

2014 North Atlantic Hurricane Season Review WHITEPAPER Executive Summary The 2014 Atlantic hurricane season was a quiet season, closing with eight 2014 marks the named storms, six hurricanes, and two major hurricanes (Category 3 or longest period on stronger). record – nine Forecast groups predicted that the formation of El Niño and below consecutive years average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Atlantic Main – that no major Development Region (MDR)1 through the season would inhibit hurricanes made development in 2014, leading to a below average season. While 2014 landfall over the was indeed quiet, these predictions didn’t materialize. U.S. The scientific community has attributed the low activity in 2014 to a number of oceanic and atmospheric conditions, predominantly anomalously low Atlantic mid-level moisture, anomalously high tropical Atlantic subsidence (sinking air) in the Main Development Region (MDR), and strong wind shear across the Caribbean. Tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic basin was also influenced by below average activity in the 2014 West African monsoon season, which suppressed the development of African easterly winds. The year 2014 marks the longest period on record – nine consecutive years since Hurricane Wilma in 2005 – that no major hurricanes made landfall over the U.S., and also the ninth consecutive year that no hurricane made landfall over the coastline of Florida. The U.S. experienced only one landfalling hurricane in 2014, Hurricane Arthur. Arthur made landfall over the Outer Banks of North Carolina as a Category 2 hurricane on July 4, causing minor damage. While Mexico and Central America were impacted by two landfalling storms and the Caribbean by three, Bermuda suffered the most substantial damage due to landfalling storms in 2014.Hurricane Fay and Major Hurricane Gonzalo made landfall on the island within a week of each other, on October 12 and October 18, respectively. -

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Dwergstern3.Pdf

99 PRIMARY MOULT, BODY MASS AND MOULT MIGRATION OF LITTLE TERN STERNAALBIFRONS IN NE ITALY GIUSEPPE CHERUBINI, LORENZO SERRA & NICOLA BACCETTI Cherubini G., L. Serra & N. Baccetti 1996. Primary moult, body mass and moult migration of Little Tern Sterna albifrons in NE Italy. Ardea 84: 99 114. Large post-breeding gatherings of Little Terns Sterna albifrons are regu larly observed in the Lagoon of Venice, Italy. Here, during five consecutive \ 1/ trapping seasons, 2956 birds were examined and ringed. Their breeding area, as indicated by 163 direct recoveries (mainly juveniles, ringed as chicks), spans over a broad sector of the Adriatic coasts, with colonies lo cated up to 133 km far. During their stay at the study area, adults undergo an almost complete moult. Two partial primary moult cycles can be ob \ served, the first of them being suspended when 2-4 outermost long primar ies have not yet been shed. Pre-migratory body mass build-up, enough for a ~/ flight longer than 1000 km, takes place during the very last days before de parture to the winter quarters, in most cases when the moult has reached a I suspended stage. Active primary moult and body mass increase do overlap in late moulting birds (after 27 August), indicating that the two processes are compatible, in case of time shortage. Post-breeding movements to the Lagoon of Venice seem to fit most requisites of moult migration. Key words: Sterna albifrons - Italy - biometrics - moult migration - ringing - fattening Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca' Fornacetta 9,1-40064 Oz zano Emilia BO, Italy. -

Modelling Global Tropical Cyclone Wind Footprints

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2019-207 Preprint. Discussion started: 2 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. Modelling Global Tropical Cyclone Wind Footprints James M. Done1,2, Ming Ge1, Greg J. Holland1,2, Ioana Dima-West3, Samuel Phibbs3, Geoffrey R. Saville3, and Yuqing Wang4 5 1National Center for Atmospheric Research, 3090 Center Green Drive, Boulder CO 80301, US 2Willis Research Network, 51 Lime St, London, EC3M 7DQ, UK 3Willis Towers Watson, 51 Lime St, London, EC3M 7DQ, UK 4International Pacific Research Center and Department of Atmospheric Sciences, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawaii at Manoa, HI 96822, US. 10 Correspondence to: James M. Done ([email protected]) Abstract. A novel approach to modelling the surface wind field of landfalling tropical cyclones (TCs) is presented. The modelling system simulates the evolution of the low-level wind fields of landfalling TCs, accounting for terrain effects. A two- step process models the gradient-level wind field using a parametric wind field model fitted to TC track data, then brings the winds down to the surface using a full numerical boundary layer model. The physical wind response to variable surface drag 15 and terrain height produces substantial local modifications to the smooth wind field provided by the parametric wind profile model. For a set of U.S. historical landfalling TCs the simulated footprints compare favourably with surface station observations. The model is applicable from single event simulation to the generation of global catalogues. One application demonstrated here is the creation of a dataset of 714 global historical TC overland wind footprints. -

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: the Importance of Artificial Sites

Terns Nesting in Boston Harbor: The Importance of Artificial Sites Jeremy J. Hatch Terns are familiar coastal birds in Massachusetts, nesting widely, but they are most numerous from Plymouth southwards. Their numbers have fluctuated over the years, and the history of the four principal species was compiled by Nisbet (1973 and in press). Two of these have nested in Boston Harbor: the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) and the Least Tern (S. albifrons). In the late nineteenth century, the numbers of all terns declined profoundly throughout the Northeast because of intensive shooting of adults for the millinery trade (Doughty 1975), reaching their nadir in the 1890s (Nisbet 1973). Subsequently, numbers rebounded and reached a peak in the 1930s, declined again to the mid-1970s, then increased into the 1990s under vigilant protection (Blodget and Livingston 1996). In contrast, the first terns to nest in Boston Harbor in the twentieth century were not reported until 1968, and there are no records from the 1930s, when the numbers peaked statewide. For much of their subsequent existence the Common Terns have depended upon a sequence of artificial sites. This unusual history is the subject of this article. For successful breeding, terns require both an abimdant food supply and nesting sites safe from predators. Islands in estuaries can be ideal in both respects, and it is likely that terns were numerous in Boston Harbor in early times. There is no direct evidence for — or against — this surmise, but one of the former islands now lying beneath Logan Airport was called Bird Island (Fig. 1) and, like others similarly named, may well have been the site of a tern colony in colonial times. -

Roseate Tern Sterna Dougallii

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada Roseate Tern. Diane Pierce © 1995 ENDANGERED 2009 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports: COSEWIC. 1999. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Whittam, R.M. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-28 pp. Kirkham, I.R. and D.N. Nettleship. 1986. COSEWIC status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 49 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Becky Whittam for writing the status report on the Roseate Tern Sterna dougallii in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Richard Cannings and Jon McCracken, Co-chairs, COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la Sterne de Dougall (Sterna dougallii) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

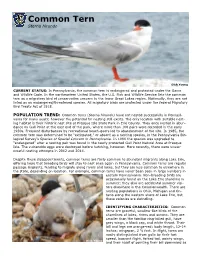

Common Tern Sterna Hirundo

Common Tern Sterna hirundo Dick Young CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the common tern is endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. In the northeastern United States, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists the common tern as a migratory bird of conservation concern in the lower Great Lakes region. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Common terns (Sterna hirundo) have not nested successfully in Pennsyl- vania for many years; however the potential for nesting still exists. The only location with suitable nest- ing habitat is their historic nest site at Presque Isle State Park in Erie County. They once nested in abun- dance on Gull Point at the east end of the park, where more than 100 pairs were recorded in the early 1930s. Frequent disturbances by recreational beach-goers led to abandonment of the site. In 1985, the common tern was determined to be “extirpated,” or absent as a nesting species, in the Pennsylvania Bio- logical Survey’s Species of Special Concern in Pennsylvania. In 1999 the species was upgraded to “endangered” after a nesting pair was found in the newly protected Gull Point Natural Area at Presque Isle. The vulnerable eggs were destroyed before hatching, however. More recently, there were unsuc- cessful nesting attempts in 2012 and 2014. Despite these disappointments, common terns are fairly common to abundant migrants along Lake Erie, offering hope that breeding birds will stay to nest once again in Pennsylvania. -

![Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0282/ciconiiformes-charadriiformes-coraciiformes-and-passeriformes-1100282.webp)

Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.]

Die Vogelwarte 39, 1997: 131-140 Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] By Reuven Yosef Abstract: R euven , Y. (1997): Clues to the Migratory Routes of the Eastern Fly way of the Western Palearctics - Ringing Recoveries at Eilat, Israel [I - Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, Coraciiformes, and Passeriformes.] Vogelwarte 39: 131-140. Eilat, located in front of (in autumn) or behind (in spring) the Sinai and Sahara desert crossings, is central to the biannual migration of Eurasian birds. A total of 113 birds of 21 species ringed in Europe were recovered either at Eilat (44 birds of 12 species) or were ringed in Eilat and recovered outside Israel (69 birds of 16 spe cies). The most common species recovered are Lesser Whitethroat {Sylvia curruca), White Stork (Ciconia cico- nia), Chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), Swallow {Hirundo rustica) Blackcap (S. atricapilla), Pied Wagtail {Motacilla alba) and Sand Martin {Riparia riparia). The importance of Eilat as a central point on the migratory route is substantiated by the fact that although the number of ringing stations in eastern Europe and Africa are limited, and non-existent in Asia, several tens of birds have been recovered in the past four decades. This also stresses the importance of taking a continental perspective to future conservation efforts. Key words: ringing, recoveries, Eilat, Eurasia, Africa. Address: International Bird Center, P. O. Box 774, Eilat 88106, Israel. 1. Introduction Israel is the only land brigde between three continents and a junction for birds migrating south be tween Europe and Asia to Africa in autumn and north to their breeding grounds in spring (Yom-Tov 1988). -

Snowy Sheathbills and What You Really Need to Know

Snowy Sheathbills and what you really need to know Reprinted from British Antarctic Survey Bulletin, No. 2, December 1963, p. 53-71 THE SHEATHBILL, Chionis alba (Gmelin), AT SIGNY ISLAND, SOUTH ORKNEY ISLANDS By N. V. Jones ABSTRACT. A study of the sheathbill, Chionis alba (Gmelin), was carried out at Signy Island, South Orkney Islands, between April 1961 and April 1962. The general characteristics of the species and the annual population cycle have been investigated. Breeding birds return to the island early in October, form pairs early in November, and establish territories later in November. There is a high level of fidelity to a previous year's mate and considerable nest-site tenacity. Nests are concentrated around penguin (Pygoscelis adetiae and P. antarctica) colonies, the closer association being with the latter species. Both sexes participate in nest construction, incubation and the care of the chick. Egg-laying begins in early December, but full incubation starts only when clutches, which number from one to four, are complete. The normal incubation period is 30 days. Chicks are fed largely on "krill", obtained by disturbing penguins which are feeding their own young, and the sheathbill's life cycle is suitably coincident with that of the penguins. Chicks fledge when 50 to 60 days old and at this stage they become shore feeders. Chicks and adults disperse from the island in about mid-May, and there is evidence of a rather loose northward migration in winter. No definite predators are known. A number of parasites have been recorded. THIS paper describes work done on the sheathbill at Signy Island (lat. -

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does Not Include Alcidae

SHOREBIRDS (Charadriiformes*) CARE MANUAL *Does not include Alcidae CREATED BY AZA CHARADRIIFORMES TAXON ADVISORY GROUP IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Charadriiformes Taxon Advisory Group. (2014). Shorebirds (Charadriiformes) Care Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Original Completion Date: October 2013 Authors and Significant Contributors: Aimee Greenebaum: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Vice Chair, Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Alex Waier: Milwaukee County Zoo, USA Carol Hendrickson: Birmingham Zoo, USA Cindy Pinger: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Chair, Birmingham Zoo, USA CJ McCarty: Oregon Coast Aquarium, USA Heidi Cline: Alaska SeaLife Center, USA Jamie Ries: Central Park Zoo, USA Joe Barkowski: Sedgwick County Zoo, USA Kim Wanders: Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA Mary Carlson: Charadriiformes Program Advisor, Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Perry: Seattle Aquarium, USA Sara Crook-Martin: Buttonwood Park Zoo, USA Shana R. Lavin, Ph.D.,Wildlife Nutrition Fellow University of Florida, Dept. of Animal Sciences , Walt Disney World Animal Programs Dr. Stephanie McCain: AZA Charadriiformes TAG Veterinarian Advisor, DVM, Birmingham Zoo, USA Phil King: Assiniboine Park Zoo, Canada Reviewers: Dr. Mike Murray (Monterey Bay Aquarium, USA) John C. Anderson (Seattle Aquarium volunteer) Kristina Neuman (Point Blue Conservation Science) Sarah Saunders (Conservation Biology Graduate Program,University of Minnesota) AZA Staff Editors: Maya Seaman, MS, Animal Care Manual Editing Consultant Candice Dorsey, PhD, Director of Animal Programs Debborah Luke, PhD, Vice President, Conservation & Science Cover Photo Credits: Jeff Pribble Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management.