On the Cusp of an Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

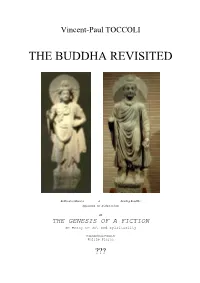

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Prehistory Unit 1

Prehistory Unit 1. What does prehistory mean? It is the time before writing. 2. What do we call ancient people who had no permanent homes but who followed and hunted animals? Nomads 3. Name one animal early man hunted that was 11 feet high and weighed over 6 tons. Woolly Mammoth 4. What early animal did nomads hunt that is now extinct? Woolly Mammoth 5. When did prehistory end? It ended about 3000 B.C., when Sumerians created cuneiform. 6. When did woolly mammoths live? Prehistoric Times 7. What do we call the time before writing? Prehistory 8. Do scientists know or think when humans began? They think. 9. Name a prehistoric building monument in Great Britain? Stonehenge 10. Name a prehistoric people who lived in Central and Eastern Europe: Celts 11. What is a pagan? It is a person who believes in many gods. 12. Where did scientists find the oldest humanlike creatures? Africa 13How long ago did the last Ice Age end? C. 12,000 years ago Basics in the Study of History 1. A century means 100 years. 2. B.C. means Before Christ. 3. A.D. means In the Year of our Lord. Ice Age 1. When did the last Ice Age end? About 12,000 years ago 2. Which pre-human creature lived from c. 350,000 B.C. to 35,000 B.C.? Neanderthal 3. Which continent is north of Africa? Europe 4. Which continent is east of Europe? Asia 5. Which ocean is east of Asia? Pacific Ocean 6. Which continent is south of Asia? Australia 7. -

Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus

“Now I have forgotten all my verses”: Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus Paul Hulsenboom Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Abstract This paper examines the use of social memory in the pastoral poetry of Virgil and Cal- purnius Siculus. A comparison of the references to Rome’s social memory in both these works points to a development of this phenomenon in Latin bucolic poetry. Whereas Vir- gil’s Eclogues express a genuine anxiety with the preservation of Rome’s ancient customs and traditions in times of political turbulence, Calpurnius Siculus’s poems address issues of a different kind with the use of references to social memory. Virgil’s shepherds see their pastoral community disseminating: they start forgetting their lays or misremem- bering verses, indicating the author’s concern with Rome’s social memory and, thereby, with the prosperity and stability of the Res Publica. Calpurnius Siculus, on the other hand, has his herdsmen strive for the emperor’s patronage and a literary career in the big city, bored as they are by the countryside. They desire a larger, more cohesive and active urban community in which they and their songs will receive the acclaim they deserve and consequently live on in Rome’s social memory. Calpurnius Siculus’s poems are, however, in contrast to Virgil’s, no longer concerned with social memory in itself. Keywords: social memory, Eclogues, Virgil, Calpurnius Siculus 14 Paul Hulsenboom Abstrakt Niniejszy artykuł omawia rolę pamięci zbiorowej w poezji idyllicznej Wergiliusza i Kalpurniusza Sykulusa. Rezultaty porównania między odwołaniem się obu autorów do rzymskiej pamięci zbiorowej wskazują na rozwój tego tematu w łacińskiej poezji bu- kolicznej. -

The Aurea Aetas and Octavianic/Augustan Coinage

OMNI N°8 – 10/2014 Book cover: volto della statua di Augusto Togato, su consessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attivitá culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma 1 www.omni.wikimoneda.com OMNI N°8 – 11/2014 OMNI n°8 Director: Cédric LOPEZ, OMNI Numismatic (France) Deputy Director: Carlos ALAJARÍN CASCALES, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Editorial board: Jean-Albert CHEVILLON, Independent Scientist (France) Eduardo DARGENT CHAMOT, Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Peru) Georges DEPEYROT, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) Jean-Marc DOYEN, Laboratoire Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164, Université de Lille 3 (France) Alejandro LASCANO, Independent Scientist (Spain) Serge LE GALL, Independent Scientist (France) Claudio LOVALLO, Tuttonumismatica.com (Italy) David FRANCES VAÑÓ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Ginés GOMARIZ CEREZO, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Michel LHERMET, Independent Scientist (France) Jean-Louis MIRMAND, Independent Scientist (France) Pere Pau RIPOLLÈS, Universidad de Valencia (Spain) Ramón RODRÍGUEZ PEREZ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Pablo Rueda RODRÍGUEZ-VILa, Independent Scientist (Spain) Scientific Committee: Luis AMELA VALVERDE, Universidad de Barcelona (Spain) Almudena ARIZA ARMADA, New York University (USA/Madrid Center) Ermanno A. ARSLAN, Università Popolare di Milano (Italy) Gilles BRANSBOURG, Universidad de New-York (USA) Pedro CANO, Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) Alberto CANTO GARCÍA, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco CEBREIRO ARES, Universidade de Santiago -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

Hasmonean” Family Tree

THE “HASMONEAN” FAMILY TREE Hasmoneus │ Simeon │ John │ Mattathias ┌──────────────┬─────────────────────┼─────────────────┬─────────┐ John Simon Judas Maccabee Eleazar Jonathan Murdered: Murdered: KIA: KIA: Murdered: 160/159 BC 134 BC 160 BC 162 BC 143 BC ┌────────┬────┴────┐ Judas John Hyrcanus Murdered: Murdered: Died: 134 BC 135 BC 104 BC ├──────────────────────┬─────────────┐ Aristobulus ═ Salome Alexander Antigonus Alexander ═══════ Salome Alexander Declared Himself “King”: Murdered: Declared “King”: Declared “Regent”: 104 BC 103 BC 103 BC 76 BC Died: Died: 103 BC 76 BC ┌──────┴──────┐ Hyrcanus II Aristobulus II Declared High Priest: 76 BC 1 THE “HASMONEAN” DYNASTY OF SIMON THE HIGH PRIEST 142 BC Simon, the last of the sons of Mattathias, was declared High Priest & “Ethnarch” (ruler of one’s own ethnic group) of the Jews by Demetrius II, King of the Seleucid Empire. 138 BC After Demetrius II was captured by the Parthians, his brother, Antiochus VII, affirmed Simon’s High Priesthood & requested assistance in dealing with Trypho, a usurper of the Seleucid throne. “King Antiochus to Simon the high priest and ethnarch and to the nation of the Jews, greetings. “Whereas certain scoundrels have gained control of the kingdom of our ancestors, and I intend to lay claim to the kingdom so that I may restore it as it formerly was, and have recruited a host of mercenary troops and have equipped warships, and intend to make a landing in the country so that I may proceed against those who have destroyed our country and those who have devastated many cities in my kingdom, now therefore I confirm to you all the tax remissions that the kings before me have granted you, and a release from all the other payments from which they have released you. -

The Late Republic in 5 Timelines (Teacher Guide and Notes)

1 180 BC: lex Villia Annalis – a law regulating the minimum ages at which a individual could how political office at each stage of the cursus honorum (career path). This was a step to regularising a political career and enforcing limits. 146 BC: The fall of Carthage in North Africa and Corinth in Greece effectively brought an end to Rome’s large overseas campaigns for control of the Mediterranean. This is the point that the historian Sallust sees as the beginning of the decline of the Republic, as Rome had no rivals to compete with and so turn inwards, corrupted by greed. 139 BC: lex Gabinia tabelleria– the first of several laws introduced by tribunes to ensure secret ballots for for voting within the assembliess (this one applied to elections of magistrates). 133 BC – the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus, who along with his younger brother, is seen as either a social reformer or a demagogue. He introduced an agrarian land that aimed to distribute Roman public land to the poorer elements within Roman society (although this act quite likely increased tensions between the Italian allies and Rome, because it was land on which the Italians lived that was be redistributed). He was killed in 132 BC by a band of senators led by the pontifex maximus (chief priest), because they saw have as a political threat, who was allegedly aiming at kingship. 2 123-121 BC – the younger brother of Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus was tribune in 123 and 122 BC, passing a number of laws, which apparent to have aimed to address a number of socio-economic issues and inequalities. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration.