Power, Politics and Personalities in Australian Astronomy: William Ernest Cooke and the Triangulation of the Pacific by Wireless Time Signals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

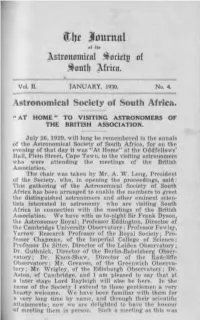

Assaj V2 N4 1930-Jan

ijtlJt Journal {If tl]t J\.strauamital ~ add!,! af ~ autb J\.frita. Vol. II. JANUARY, 1930. No.4. Astronomical Society of South Africa~ "' AT HOME" TO VISITING ASTRONOMERS OF THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION. July 26, 1929, will long be remembered in the annals of the Astronomical Society of South Africa, for on the evening of that day it was "At Home" at the Oddfellows' Hall, Plein Street, Cape Town, to the visiting astronomers who were attending the meetings of the British Association. The chair was taken by Mr. A. W. Long, President of the Society, who, in opening the proceedings, said: This gathering of the Astronomical Society of South Africa has been arranged to enable the members to greet the distinguished astronomers and other eminent scien tists interested in astronomy who are visiting South Africa in connection with the meetings of the British Association. We have with us to-night Sir Frank Dyson, the Astronomer Royal; Professor Eddington, Director of the Cambridge University Observatory; Professor Fowl~r, Yarrow Research Professor of the Royal Society; Pro fessor Chapman, of the Imperial College of Science; Professor De Sitter, Director of the Leiden Observatory; Dr. Guthnick, Director of the Berlin-Babelsberg Obser vatory; Dr. K110x-Shaw, Director of the Radcliffe Observatory; Mr. Greaves, of the Greenwich Observa tory; Mr. Wrigley, of the Edinburgh Observatory; Dr. Aston, of Cambridge, and I am pleased to say that at a later stage Lord Rayleigh will also be here. In the name of the Society I extend to these gentlemen a very hearty welcome. We have been familiar with them for a very long time by name, and through their scientific attainments; now we are delighted to have the honour of meeting them in person. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers Past Masters Since 1631

The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers Past Masters since 1631 1631 David Ramsey (named in the Charter) 1700 Charles Gretton 1800 Matthew Dutton 1632 David Ramsey (sworn 22nd October) 1701 William Speakman 1801 William Plumley 1633 David Ramsey, represented by his Deputy, Henry Archer 1702 Joseph Windmills 1802 Edward Gibson 1634 Sampson Shelton 1703 Thomas Tompion 1803 Timothy Chisman 1635 John Willow 1704 Robert Webster 1804 William Pearce 1636 Elias Allen 1705 Benjamin Graves 1805 William Robins 1638 John Smith 1706 John Finch 1806 Francis S Perigal Jnr 1639 Sampson Shelton 1707 John Pepys 1807 Samuel Taylor 1640 John Charleton 1708 Daniel Quare 1808 Thomas Dolley 1641 John Harris 1709 George Etherington 1809 William Robson 1642 Richard Masterson 1710 Thomas Taylor 1810 Paul Philip Barraud 1643 John Harris 1711 Thomas Gibbs 1811 Paul Philip Barraud 1644 John Harris 1712 John Shaw 1812 Harry Potter (died) 1645 Edward East 1713 Sir George Mettins (Lord Mayor 1724–1725) 1813 Isaac Rogers 1646 Simon Hackett 1714 John Barrow 1814 William Robins 1647 Simon Hackett 1715 Thomas Feilder 1815 John Thwaites 1648 Robert Grinkin 1716 William Jaques 1816 William Robson 1649 Robert Grinkin 1717 Nathaniel Chamberlain 1817 John Roger Arnold 1650 Simon Bartram 1718 Thomas Windmills 1818 William Robson 1651 Simon Bartram 1719 Edward Crouch 1819 John Thwaites 1652 Edward East 1720 James Markwick 1820 John Thwaites 1653 John Nicasius 1721 Martin Jackson 1821 Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy 1654 Robert Grinkin 1722 George Graham 1822 John Jackson Jnr 1655 John Nicasius -

Historical Earthquakes in Western Australia Kevin Mccue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra ACT

Historical Earthquakes in Western Australia Kevin McCue Australian Seismological Centre, Canberra ACT. Abstract This paper is a tabulation and description of some earthquakes and tsunamis in Western Australia that occurred before the first modern short-period seismograph installation at Watheroo in 1958. The purpose of investigating these historical earthquakes is to better assess the relative earthquake hazard facing the State than would be obtained using just data from the post–modern instrumental period. This study supplements the earlier extensive historical investigation of Everingham and Tilbury (1972). It was made possible by the Australian National library project, TROVE, to scan and make available on-line Australian newspapers published before 1954. The West Australian newspaper commenced publication in Perth in 1833. Western Australia is rather large with a sparsely distributed population, most of the people live along the coast. When an earthquake is felt in several places it would indicate a larger magnitude than one in say Victoria felt at a similar number of sites. Both large interplate and local intraplate earthquakes are felt in the north-west and sometimes it is difficult to identify the source because not all major historical earthquakes on the plate boundary are tabulated by the ISC or USGS. An earthquake on 29 April 1936 is a good example, local or distant source? An interesting feature of the large earthquakes in WA is their apparent spatial and temporal migration, the latter alluded to by Everingham and Tilbury (1972). One could deduce that the seismicity rate changed before the major earthquake in 1906 offshore the central west coast of WA. -

Download This Article (Pdf)

244 Trimble, JAAVSO Volume 43, 2015 As International as They Would Let Us Be Virginia Trimble Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697-4575; [email protected] Received July 15, 2015; accepted August 28, 2015 Abstract Astronomy has always crossed borders, continents, and oceans. AAVSO itself has roughly half its membership residing outside the USA. In this excessively long paper, I look briefly at ancient and medieval beginnings and more extensively at the 18th and 19th centuries, plunge into the tragedies associated with World War I, and then try to say something relatively cheerful about subsequent events. Most of the people mentioned here you will have heard of before (Eratosthenes, Copernicus, Kepler, Olbers, Lockyer, Eddington…), others, just as important, perhaps not (von Zach, Gould, Argelander, Freundlich…). Division into heroes and villains is neither necessary nor possible, though some of the stories are tragic. In the end, all one can really say about astronomers’ efforts to keep open channels of communication that others wanted to choke off is, “the best we can do is the best we can do.” 1. Introduction astronomy (though some of the practitioners were actually Christian and Jewish) coincided with the largest extents of Astronomy has always been among the most international of regions governed by caliphates and other Moslem empire-like sciences. Some of the reasons are obvious. You cannot observe structures. In addition, Arabic astronomy also drew on earlier the whole sky continuously from any one place. Attempts to Greek, Persian, and Indian writings. measure geocentric parallax and to observe solar eclipses have In contrast, the Europe of the 16th century, across which required going to the ends (or anyhow the middles) of the earth. -

One of the Most Celebrated Physics Experiments of the 20Th Cent

Not Only Because of Theory: Dyson, Eddington and the Competing Myths of the 1919 Eclipse Expedition Introduction One of the most celebrated physics experiments of the 20th century, a century of many great breakthroughs in physics, took place on May 29th, 1919 in two remote equatorial locations. One was the town of Sobral in northern Brazil, the other the island of Principe off the west coast of Africa. The experiment in question concerned the problem of whether light rays are deflected by gravitational forces, and took the form of astrometric observations of the positions of stars near the Sun during a total solar eclipse. The expedition to observe the eclipse proved to be one of those infrequent, but recurring, moments when astronomical observations have overthrown the foundations of physics. In this case it helped replace Newton’s Law of Gravity with Einstein’s theory of General Relativity as the generally accepted fundamental theory of gravity. It also became, almost immediately, one of those uncommon occasions when a scientific endeavor captures and holds the attention of the public throughout the world. In recent decades, however, questions have been raised about possible bias and poor judgment in the analysis of the data taken on that famous day. It has been alleged that the best known astronomer involved in the expedition, Arthur Stanley Eddington, was so sure beforehand that the results would vindicate Einstein’s theory that, for unjustifiable reasons, he threw out some of the data which did not agree with his preconceptions. This story, that there was something scientifically fishy about one of the most famous examples of an experimentum crucis in the history of science, has now become well known, both amongst scientists and laypeople interested in science. -

November 2019

A selection of some recent arrivals November 2019 Rare and important books & manuscripts in science and medicine, by Christian Westergaard. Flæsketorvet 68 – 1711 København V – Denmark Cell: (+45)27628014 www.sophiararebooks.com AMPÈRE, André-Marie. THE FOUNDATION OF ELECTRO- DYNAMICS, INSCRIBED BY AMPÈRE AMPÈRE, Andre-Marie. Mémoires sur l’action mutuelle de deux courans électri- ques, sur celle qui existe entre un courant électrique et un aimant ou le globe terres- tre, et celle de deux aimans l’un sur l’autre. [Paris: Feugeray, 1821]. $22,500 8vo (219 x 133mm), pp. [3], 4-112 with five folding engraved plates (a few faint scattered spots). Original pink wrappers, uncut (lacking backstrip, one cord partly broken with a few leaves just holding, slightly darkened, chip to corner of upper cov- er); modern cloth box. An untouched copy in its original state. First edition, probable first issue, extremely rare and inscribed by Ampère, of this continually evolving collection of important memoirs on electrodynamics by Ampère and others. “Ampère had originally intended the collection to contain all the articles published on his theory of electrodynamics since 1820, but as he pre- pared copy new articles on the subject continued to appear, so that the fascicles, which apparently began publication in 1821, were in a constant state of revision, with at least five versions of the collection appearing between 1821 and 1823 un- der different titles” (Norman). The collection begins with ‘Mémoires sur l’action mutuelle de deux courans électriques’, Ampère’s “first great memoir on electrody- namics” (DSB), representing his first response to the demonstration on 21 April 1820 by the Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851) that electric currents create magnetic fields; this had been reported by François Arago (1786- 1853) to an astonished Académie des Sciences on 4 September. -

STANDARD STARS for COMET PHOTOMETRY Wayne Osborn

STANDARD STARS FOR COMET PHOTOMETRY Wayne Osborn Physics Department, Central Michigan University Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 48859, U.S.A. Peter Birch Perth Observatory Bickley, Western Australia 6076, Australia Michael Feierberg Astronomy Program, University of Maryland College Park, Maryland 20742, U.S.A. ABSTRACT. Photoelectric photometry of comets is a feasible and worth- while research program for small telescopes. Nine filters designed to isolate selected emission features and continuum regions in cometary spectra have been adopted by the IAU as those recommended for comet photometry. Magnitudes of standard stars for the IAU filter system have been derived. The results have been compared with previous observations and transformations to place all observations on a common system obtained. 1. INTRODUCTION A profitable research program for small telescopes is the photoelectric monitoring of comets. Because comets appear suddenly and most studies require measurements made over an extended period of time, observations with larger, heavily scheduled instruments are often impossible. Furthermore, comets are extended objects and for projects involving the comet's integrated brightness a small scale is preferable. We have established a system of photoelectric standards intended for comet photometry. 2. COMET PHOTOMETRY Comet photometry can be divided into two types: studies of the continuum and studies of emission lines. Continuum observations are directed toward understanding the dust component of the comet, and ideally only involve measures of reflectivity of the solar spectrum. The emission line studies are concerned with the production of the components of the 313 J. B. Hearnshaw and P. L. Cottrell (eds.), Instrumentation and Research Programmes for Small Telescopes, 313-314. -

Michael Philip Candy (1928-1994)

Notes and News Obituary Michael Philip Candy (1928-1994) Michael Candy was born at Bath, Somerset, Cepheus. Although he spent many hours in the Organising Committee of the Inter on 1928 December 23, the eldest of six chil further searches, it was to be his only comet national Astronomical Union Commission dren. He joined HM Nautical Almanac discovery. 20 (Positions and Motions of Minor Planets, Office, then located in Bath, in 1947 During his term as Director of the Comet Comets and Satellites) (1979-1988), Vice- September. In 1949 the ΝΑΟ moved to the Section Candy greatly encouraged both President of IAU Commission 6 (Astro Royal Greenwich Observatory's new site at established Section members and newcom nomical Telegrams) (1979-1982) and its Herstmonceux Castle in Sussex. ers. He had a friendly manner and was President (1982-1985). He was appointed Mike Candy was elected to membership always approachable. He found time to Acting Government Astronomer (Acting of the Association on 1950 November 29 reply to letters and acknowledged observa Director of the Perth Observatory) in 1984 and was particularly interested in comput tions, usually by postcard in his own clear and later confirmed as Government Astron ing and the smaller bodies of the Solar hand, adding useful bits of information or an omer and Director. Asteroid 3015 Candy System, and put his skills to good use extended ephemeris. was named after him for his work on south computing orbits for recently discovered During this time Candy was also busy ern hemisphere astronomy. He also served comets. Dr Gerald Merton was Director of with his professional astronomical career, as Councillor of the Astronomical Society the Comet Section when comet Arend- moving to the Astronomer Royal's Depart of Australia (1988-1990), and Councillor Roland was discovered in 1956 November, ment in 1958, taking a Bachelor of Science (1988-1990) and President (1989) of the and Candy computed a series of orbits as degree at London in 1963 and a Master of Royal Society of Western Australia. -

Frank Schlesinger 1871-1943

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XXIV THIRD MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF FRANK SCHLESINGER 1871-1943 BY DIRK BROUWER PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1945 FRANK SCHLESINGER 1871-1943 BY DIRK BROUWER Frank Schlesinger was born in New York City on May n, 1871. His father, William Joseph Schlesinger (1836-1880), and his mother, Mary Wagner Schlesinger (1832-1892), both natives of the German province of Silesia, had emigrated to the United States. In Silesia they had lived in neighboring vil- lages, but they did not know each other until they met in New York, in 1855, at the home of Mary's cousin. They were mar- ried in 1857 and had seven children, all of whom grew to maturity. Frank was the youngest and, after 1939, the last survivor. His father's death, in 1880, although it brought hardships to the family, was not permitted to interfere with Frank's educa- tion. He attended public school in New York City, and eventually entered the College of the City of New York, receiv- ing the degree of Bachelor of Science in 1890. His aptitude for mathematical science, already evident in grammar school, be- came more marked in the higher stages of his education when he began to show a preference for applied mathematics. Upon completing his undergraduate work it was not possible for him to continue with graduate studies. He had to support himself, and his health at that time made it desirable for him to engage in outdoor activities. -

SOLAR ECLIPSE NEWSLETTER SOLAR ECLIPSE March 2004 NEWSLETTER

Volume 9, Issue 3 SOLAR ECLIPSE NEWSLETTER SOLAR ECLIPSE March 2004 NEWSLETTER The sole Newsletter dedicated to Solar Eclipses INDEX 1 Picture Josch Hambsch dscn1394_crop_ps_red2 Dear All, 2 SECalendar March 8 SECalendar for March - typos Another Solar Eclipse Newsletter. It’ brings us closer to the in- 8 SECalendar for March - Data ternational Solar Eclipse Conference. The program is quite fixed 9 SEC2004 WebPages update and the registrations are coming in quickly. Many magazines 10 SENL Index February will publish and announce the conference shortly and we hope 10 Eclipse sightings 10 SENL for all of 3003 now online of course to have a sold out theatre at the Open University of 11 16 - 9 wide screen video problem Milton Keynes. Unfortunately, Jean Meeus had to cancel. He 11 Cloud cover maps suffers lately with some health problems and prefers to attend- 12 Old eclipse legends (?) ing the conference. 13 Free! Copies of NASA's 2003 eclipse bulletin 13 Delta T But even more: The Transit of Venus is due soon. The amount 14 BAA Journal web pages of messages, on the SEML and on other mailing lists, show. 14 Eclipse music Many trips are booked and of course we all hope for the best 14 Max number of Consecutive non-central annular eclipses clear skies. This event does not happen that often and we do 16 24 years ago.... not want miss it. 17 Lunar Eclipse papers 17 Saros 0 and EMAPWIN And what about the partial solar eclipse of April. A few SEML 18 Urgent - Klipsi needs photos of Klipsi subscribers will observe from the southern part of Africa and we 19 For eclipse chasers .. -

Schweifsternen Des Letzten Quartals Mehr Als Zufrieden

Mitteilungsblatt der Heft 173 (34. Jahrgang) ISSN (Online) 2511-1043 Februar 2018 Komet C/2016 R2 (PanSTARRS) am 10. Januar 2018 um 20:26 UT mit einem 12“ f/3,6 ASA Astrograph, RGB 32/12/12 Minuten belichtet mit einer FLI PL16200 CCD-Kamera, Gerald Rhemann Liebe Kometenfreunde, wann gibt es wieder einen hellen Kometen? Fragt man hin und wieder im Internet. Ich dagegen vermisse nichts und bin mit den Schweifsternen des letzten Quartals mehr als zufrieden. Herausheben möchte ich die Schweifdynamik, welche der Komet C/2016 R2 (PanSTARRS) hervorbringt (siehe Titelfoto): Sie wurde von einigen von uns fotografiert, die raschen Veränderungen im Schweif erinnerte nicht nur mich an eine sich drehende Qualle. Michael Jäger und ich werden darüber im VdS-Journal berichten. Viel eindrucksvoller als die dort abgedruckten Fotos sind aber die kleinen Videofilme, die man in unserer Bildergalerie findet. Visuell war davon praktisch nichts zu sehen. Nur in Instrumenten der Halbmeterklasse war überhaupt etwas vom Schweif erkennbar, in meinem 12-Zöller sah ich nur die Koma. Für mich ist dies ein plastischer Nachweis, wie sehr sich die Kometenfotografie entwickelt hat. Einen klaren Himmel wünscht Euer Uwe Pilz. Liebe Leser des Schweifsterns, Die vorliegende Ausgabe des Schweifsterns deckt die Aktivitäten der Fachgruppe Kometen der VdS im Zeitraum vom 01.11.2017 bis zum 31.01.2018 ab. Berücksichtigt wurden alle bis zum Stichtag be- reitgestellten Fotos, Daten und Beiträge (siehe Impressum am Ende des Schweifsterns). Für die einzelnen Kometen lassen sich die Ephemeriden der Kometen auf der Internet-Seite http://www.minorplanetcenter.org/iau/MPEph/MPEph.html errechnen.